Report on the Right to Health in Guinea-Bissau April 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People's Health Movement Annual Report 2018

People’s Health Movement Annual Report 2018 1 Contents 1. About PHM ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Highlights from 2018 ...................................................................................................................... 3 3. Global Health Watch ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. Global Governance for Health - WHO watch ................................................................................ 5 5. The International People’s Health University – IPHU ................................................................... 7 6. Health for All Campaign ................................................................................................................. 7 7. People’s Health Assembly .............................................................................................................. 9 8. Communications ........................................................................................................................... 11 9. Statements/Conferences/Publications ....................................................................................... 11 10 Governance ............................................................................................................................... 12 11 Regional Activities ................................................................................................................... -

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention in Guinea Maya Zhang, Stacy Attah-Poku, Noura Al-Jizawi, Jordan Imahori, Stanley Zlotkin

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention in Guinea Maya Zhang, Stacy Attah-Poku, Noura Al-Jizawi, Jordan Imahori, Stanley Zlotkin April 2021 This research was made possible through the Reach Alliance, a partnership between the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. Research was also funded by the Ralph and Roz Halbert Professorship of Innovation at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy. We express our gratitude and appreciation to those we met and interviewed. This research would not have been possible without the help of Dr. Paul Milligan from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, ACCESS-SMC, Catholic Relief Services, the Government of Guinea and other individuals and organizations in providing and publishing data and resources. We are also grateful to Dr. Kovana Marcel Loua, director general of the National Institute of Public Health in Guinea and professor at the Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry, Guinea. Dr. Loua was instrumental in the development of this research — advising on key topics, facilitating ethics board approval in Guinea and providing data and resources. This research was vetted by and received approval from the Ethics Review Board at the University of Toronto. Research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in compliance with local public health measures. MASTERCARD CENTER FOR INCLUSIVE GROWTH The Center for Inclusive Growth advances sustainable and equitable economic growth and financial inclusion around the world. Established as an independent subsidiary of Mastercard, we activate the company’s core assets to catalyze action on inclusive growth through research, data philanthropy, programs, and engagement. -

70Th World Health Assembly

IFMSA report on the 70th World Health Assembly IFMSA President The International Federation of Medical Students’ Omar Cherkaoui [email protected] Associations (IFMSA) is a non-profit, non-governmental Vice President for Activities organization representing associations of medical students Dominic Schmid worldwide. IFMSA was founded in 1951 and currently [email protected] maintains 132 National Member Organizations from 124 Vice President for Finance Joakim Bergman countries across six continents, representing a network of [email protected] 1.3 million medical students. Vice President for Members Monica Lauridsen Kujabi IFMSA envisions a world in which medical students unite [email protected] for global health and are equipped with the knowledge, Vice President for External Affairs skills and values to take on health leadership roles locally Marie Hauerslev [email protected] and globally, so to shape a sustainable and healthy future. Vice President for Capacity Building IFMSA is recognized as a nongovernmental organization Andrej Martin Vujkovac within the United Nations’ system and the World Health [email protected] Organization; and works in collaboration with the World Vice President for PR & Communication Firas R. Yassine Medical Association. [email protected] Publisher International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations (IFMSA) This is an IFMSA Publication Notice © 2017 - Only portions of this publication All reasonable precautions have been International Secretariat: may be reproduced for non political and taken by the IFMSA to verify the information c/o Academic Medical Center non profit purposes, provided mentioning contained in this publication. However, the Meibergdreef 15 1105AZ the source. published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either Amsterdam, The Netherlands Disclaimer expressed or implied. -

Initial Report Submitted by Guinea Pursuant to Articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant, Due in 1990*

United Nations E/C.12/GIN/1 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 16 May 2019 English Original: French English, French, and Spanish only Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Initial report submitted by Guinea pursuant to articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant, due in 1990* [Date received: 29 March 2019] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.19-08043 (E) 050819 060819 E/C.12/GIN/1 Contents Page Part 1: General information about Guinea ..................................................................................... 3 I. Geography ..................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Demographic, economic and social characteristics of Guinea ...................................................... 3 III. Constitutional, political and legal structure of Guinea .................................................................. 5 IV. General framework for the protection and promotion of human rights in Guinea ........................ 6 Part 2: Information on articles 1 to 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ............................................................................................................. 12 Article 1: Right to self-determination............................................................................................ 12 Article 2: International cooperation ............................................................................................. -

Human Rights and Constitution Making Human Rights and Constitution Making

HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING New York and Geneva, 2018 II HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTION MAKING Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations publication issued by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Photo credit: © Ververidis Vasilis / Shutterstock.com The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a figure indicates a reference to a United Nations document. HR/PUB/17/5 © 2018 United Nations All worldwide rights reserved Sales no.: E.17.XIV.4 ISBN: 978-92-1-154221-9 eISBN: 978-92-1-362251-3 CONTENTS III CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 I. CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS AND HUMAN RIGHTS ......................... 2 A. Why a rights-based approach to constitutional reform? .................... 3 1. Framing the issue .......................................................................3 2. The constitutional State ................................................................6 3. Functions of the constitution in the contemporary world ...................7 4. The constitution and democratic governance ..................................8 5. -

EB148/29 148Th Session 11 January 2021 Provisional Agenda Item 17.4

EXECUTIVE BOARD EB148/29 148th session 11 January 2021 Provisional agenda item 17.4 Status of collection of assessed contributions, including Member States in arrears in the payment of their contributions to an extent that would justify invoking Article 7 of the Constitution Situation in respect of 2019 Report by the Director-General DEFERRAL OF DECISION ON MEMBER STATES IN ARREARS 1. In November 2020, the Seventy-third World Health Assembly adopted decision WHA73(31), in which it decided to defer a decision on the status of collection of assessed contributions, including Member States in arrears in the payment of their contributions to an extent that would justify involving Article 7 of the Constitution to the Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly, on the understanding that the Health Assembly would take up this matter on the basis of a report providing an update on the situation and supplying any pertinent additional information, by the Executive Board, through its Programme, Budget and Administration Committee. 2. At the time of the opening of the Seventy-third World Health Assembly, three Member States had reduced their arrears to a level below the amount that would justify invoking Article 7, and another proceeded to do so after the resumed session of the Seventy-third World Health Assembly in December 2020. However nine Member States are still subject to Article 7, since no further payments of arrears have been received from them. These Member States are named in paragraph 12 below and amounts due from them are shown in Annex 4. 3. Another eight Member States listed in paragraphs 9, 10 and 11 had voting rights whose suspension either started or continued at the start of the Seventy-third World Health Assembly, for non-payment of arrears or unpaid special arrangements. -

57Th DIRECTING COUNCIL 71St SESSION of the REGIONAL COMMITTEE of WHO for the AMERICAS Washington, D.C., USA, 30 September-4 October 2019

57th DIRECTING COUNCIL 71st SESSION OF THE REGIONAL COMMITTEE OF WHO FOR THE AMERICAS Washington, D.C., USA, 30 September-4 October 2019 Provisional Agenda Item 4.8 CD57/10 25 July 2019 Original: English STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HEALTH PROMOTION WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS 2019-2030 Introduction 1. This Strategy and Plan of Action on Health Promotion within the Context of the Sustainable Development Goals 2019-2030 seeks to renew health promotion (HP) through social, political, and technical actions, addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age (1). It seeks to improve health and reduce health inequities within the framework of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As one of the most unequal regions in the world, the Region of the Americas will benefit from a strategic vision for health promotion that helps to increase health equity. The intention is to enable people to improve their health by moving beyond a focus on individual behavior toward a wide range of social and environmental interventions.1 Background 2. Based on the global commitment to health promotion set forth in the Declaration of Alma Ata (1978) (2) and the Ottawa Charter (1986) (3), the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Promotion Conferences call for the development of healthy public policies (4), the creation of healthy settings (5), and the building of capacities to address the social determinants of health through an HP approach (6-8). The countries of the Region of the Americas have reaffirmed these commitments many times over the years (9-27) and have sought to implement HP approaches to reduce health inequities, empower communities, and improve health throughout the life course. -

Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ISBN 978 92 4 151355 5 http://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/2017/en/ Public Disclosure Authorized Tracking Universal Health Coverage: http://www.worldbank.org/health 2017 Global Monitoring Report Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report ISBN 978-92-4-151355-5 © World Health Organization and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO or The World Bank endorse any specic organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo or The World Bank logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO) or The World Bank. WHO and The World Bank are not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The Route of the Land’s Roots: Connecting life-worlds between Guinea-Bissau and Portugal through food-related meanings and practices Maria Abranches Doctoral Thesis PhD in Social Anthropology UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX 2013 UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX PhD in Social Anthropology Maria Abranches Doctoral Thesis The Route of the Land’s Roots: Connecting life-worlds between Guinea-Bissau and Portugal through food-related meanings and practices SUMMARY Focusing on migration from Guinea-Bissau to Portugal, this thesis examines the role played by food and plants that grow in Guinean land in connecting life-worlds in both places. Using a phenomenological approach to transnationalism and multi-sited ethnography, I explore different ways in which local experiences related to food production, consumption and exchange in the two countries, as well as local meanings of foods and plants, are connected at a transnational level. One of my key objectives is to deconstruct some of the binaries commonly addressed in the literature, such as global processes and local lives, modernity and tradition or competition and solidarity, and to demonstrate how they are all contextually and relationally entwined in people’s life- worlds. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

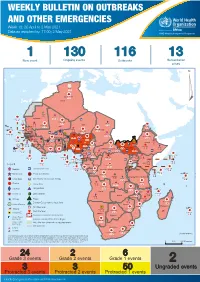

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

Republic of Guinea-Bissau Ministry of Public Health, Family and Social Cohesion Institute for Women and Children

Republic of Guinea-Bissau Ministry of Public Health, Family and Social Cohesion Institute for Women and Children 1st Implementation Report of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (2008 - 2018) Bissau, October TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms and Abbreviations...............................................4 I. INTRODUCTION...........................................................7 II. METHODOLOGY OF WORK. ...............................................12 2.1 Methodology for the Drafting of the Report on the Implementation of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, is based on.......................................................................................12 III. GENERAL IMPLEMENTATION OR ENFORCEMENT MEASURES……......................................14 3.1. Legislation and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child –ACRWC............... 14 a) National Legal Instruments Relating to the Rights of the Child........................................................ 15 45. (b) International legal instruments of human rights, particularly the children’s rights, to which Guinea-Bissau is a party .................................................................................................................... 16 3.2 Policy Measures, Programs and Actions for the Implementation of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.............................................................................................................17 3.3. Mechanisms for the Implementation -

Water Diseases: Dynamics of Malaria and Gastrointestinal Diseases in the Tropical Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) Sandra Cristina De Oliveira Alves M 2018

MESTRADO SAÚDE PÚBLICA Water diseases: dynamics of malaria and gastrointestinal diseases in the tropical Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) Sandra Cristina de Oliveira Alves M 2018 Water diseases: dynamics of malaria and gastrointestinal diseases in the tropical Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) Master in Public Health || Thesis || Sandra Cristina de Oliveira Alves Supervisor: Prof. Doutor Adriano A. Bordalo e Sá Institute Biomedical Sciences University of Porto Porto, September 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to show, in first place, my thankfulness to my supervisor Professor Adriano Bordalo e Sá, for “opening the door” to this project supplying the logbook raw data of Bolama Regional Hospital as well as meteorological data from the Serviço de Meterologia of Bolama, for is orientation and scientific support. The Regional Director of the Meteorological survey in Bolama, D. Efigénia, is thanked for supplying the values precipitation and temperature, retrieved from manual spread sheets. My gratitude also goes to all the team of the Laboratory Hydrobiology and Ecology, ICBAS-UP, who received me in a very friendly way, and always offers me their help (and cakes). An especial thanks to D. Lurdes Lima, D. Fernanda Ventura, Master Paula Salgado and Master Ana Machado (Ana, probable got one or two wrinkles for truly caring), thank you. Many many thanks to my friends, and coworkers, Paulo Assunção and Ana Luísa Macedo, who always gave me support and encouragement. Thank you to my biggest loves, my daughter Cecilia and to the ONE Piero. Thank you FAMILY, for the shared DNA and unconditional love. Be aware for more surprises soon. Marisa Castro, my priceless friend, the adventure never ends! This path would have been so harder and lonely without you.