Harvard Mountaineering 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Script

Feb rua rg 1968 North Cascades Conservation Council P. 0. Box 156 Un ? ve rs i ty Stat i on Seattle, './n. 98 105 SCRIPT FOR NORTH CASCAOES SLIDE SHOW (75 SI Ides) I ntroduct Ion : The North Cascades fiountatn Range In the State of VJashington Is a great tangled chain of knotted peaks and spires, glaciers and rivers, lakes, forests, and meadov;s, stretching for a 150 miles - roughly from Pt. fiainier National Park north to the Canadian Border, The h undreds of sharp spiring mountain peaks, many of them still unnamed and relatively unexplored, rise from near sea level elevations to seven to ten thousand feet. On the flanks of the mountains are 519 glaciers, in 9 3 square mites of ice - three times as much living ice as in all the rest of the forty-eight states put together. The great river valleys contain the last remnants of the magnificent Pacific Northwest Rain Forest of immense Douglas Fir, cedar, and hemlock. f'oss and ferns carpet the forest floor, and wild• life abounds. The great rivers and thousands of streams and lakes run clear and pure still; the nine thousand foot deep trencli contain• ing 55 mile long Lake Chelan is one of tiie deepest canyons in the world, from lake bottom to mountain top, in 1937 Park Service Study Report declared that the North Cascades, if created into a National Park, would "outrank in scenic quality any existing National Park in the United States and any possibility for such a park." The seven iiiitlion acre area of the North Cascades is almost entirely Fedo rally owned, and managed by the United States Forest Service, an agency of the Department of Agriculture, The Forest Ser• vice operates under the policy of "multiple use", which permits log• ging, mining, grazing, hunting, wt Iderness, and alI forms of recrea• tional use, Hov/e ve r , the 1937 Park Study Report rec ornmen d ed the creation of a three million acre Ice Peaks National Park ombracing all of the great volcanos of the North Cascades and most of the rest of the superlative scenery. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES October-November 1969 2 THE WILD CASCADES FARTHEST EAST: CHOPAKA MOUNTAIN Field Notes of an N3C Reconnaissance State of Washington, school lands managed by May 1969 the Department of Natural Resources. The absolute easternmost peak of the North Cascades is Chopaka Mountain, 7882 feet. An This probably is the most spectacular chunk abrupt and impressive 6700-foot scarp drops of alpine terrain owned by the state. Certain from the flowery summit to blue waters of ly its fame will soon spread far beyond the Palmer Lake and meanders of the Similka- Okanogan. Certainly the state should take a mean River, surrounded by green pastures new, close look at Chopaka and develop a re and orchards. Beyond, across this wide vised management plan that takes into account trough of a Pleistocene glacier, roll brown the scenic and recreational resources. hills of the Okanogan Highlands. Northward are distant, snowy beginnings of Canadian ranges. Far south, Tiffany Mountain stands above forested branches of Toats Coulee Our gang became aware of Chopaka on the Creek. Close to the west is the Pasayten Fourth of July weekend of 1968 while explor Wilderness Area, dominated here by Windy ing Horseshoe Basin -- now protected (except Peak, Horseshoe Mountain, Arnold Peak — from Emmet Smith's cattle) within the Pasay the Horseshoe Basin country. Farther west, ten Wilderness Area. We looked east to the hazy-dreamy on the horizon, rise summits of wide-open ridges of Chopaka Mountain and the Chelan Crest and Washington Pass. were intrigued. To get there, drive the Okanogan Valley to On our way to Horseshoe Basin we met Wil Tonasket and turn west to Loomis in the Sin- lis Erwin, one of the Okanoganites chiefly lahekin Valley. -

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....……………

MAY 2006 VOLUME 48 NUMBER 5 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: Baseball-to-softball sized hail fell from a supercell just east of Seminole in Gaines County, Texas on May 5, 2006. The supercell also produced 5 tornadoes (4 F0’s 1 F2). No deaths or injuries were reported due to the hail or tornadoes. (Photo courtesy: Matt Jacobs.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....……………...........…............ 5 Additions/Corrections.......................................................................................................................... 406 Reference Notes .............……...........................……….........…..……........................................... 427 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events -

Maine Alumnus, Volume 59, Number 1, Winter 1978

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines University of Maine Publications Winter 1978 Maine Alumnus, Volume 59, Number 1, Winter 1978 General Alumni Association, University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation General Alumni Association, University of Maine, "Maine Alumnus, Volume 59, Number 1, Winter 1978" (1978). University of Maine Alumni Magazines. 301. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines/301 This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. * be back in Maine... To once again savor its good life and now share that exhilarating experience with my family. Io both entertain and serve all who love this great State by continuing publication of the Magazine of Maine along the lines developed over the past twenty-three years by its founder — now editor emeritus — Duane Doolittle. Io join Down East Editor Dave Thomas in maintaining established standards of recalling Maine's fascinating past, reporting her vital pre sent, and revealing the potential of her future. And to improve upon those respected standards where possible. [t's an exciting challenge and one which, we believe, has already been excitingly engaged — both in picture and in word — to make Down East now — more than ever before — The Magazine of Maine. And now Down East is a Maine excitement you can enjoy eleven times a year instead of ten. -

2018 White Mountains of Maine

2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Handbook 2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Welcome to the 2018 Family Nature Summit! We are thrilled that you have chosen to join us this summer at the Sunday River Resort in the White Mountains of Maine! Whether this is your first time or your fifteenth, we know you appreciate the unparalleled value your family receives from attending a Family Nature Summit. One of the aspects that is unique about the Family Nature Summits program is that children have their own program with other children their own age during the day while the adults are free to choose their own classes and activities. Our youth programs are run by experienced and talented environmental educators who are very adept at providing a fun and engaging program for children. Our adult classes and activities are also taught by experts in their fields and are equally engaging and fun. In the afternoon, there are offerings for the whole family to do together as well as entertaining evening programs. Family Nature Summits is fortunate to have such a dedicated group of volunteers who have spent countless hours to ensure this amazing experience continues year after year. This handbook is designed to help orient you to the 2018 Family Nature Summit program. We look forward to seeing you in Maine! Page 2 2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Table of Contents Welcome to the 2018 Family Nature Summit! 2 Summit Information 7 Summit Location 7 Arrival and Departure 7 Room Check-in 7 Summit Check-in 7 Group Picture 8 Teacher Continuing Education -

Characteristics of the Ecoregions of New England 5 8

Summary Table: Characteristics of the Ecoregions of New England 5 8 . NORTHEASTERN HIGHLANDS 5 9 . NORTHEASTERN COASTAL ZONE Level IV Ecoregions Physiography Geology Soils Climate Natural Vegetation Land Cover and Land Use Level IV Ecoregions Physiography Geology Soils Climate Natural Vegetation Land Cover and Land Use Area Elevation / Surficial and Bedrock Order (Great Group) Common Soil Series Temperature / Precipitation Frost Free Mean Temperature Area Elevation / Surficial and Bedrock Order (Great Group) Common Soil Series Temperature / Precipitation Frost Free Mean Temperature (square Local Relief Moisture Mean annual Mean annual January min/max; (square Local Relief Moisture Mean annual Mean annual January min/max; miles) (feet) Regimes (inches) (days) July min/max (oF) miles) (feet) Regimes (inches) (days) July min/max (oF) 58a. Taconic 584 Low mountains and high hills, gently 600-3816 / Quaternary loamy till and sandy loamy till, valley Inceptisols (Dystrudepts) Taconic, Macomber, Frigid / 38-64 100-140 10/28; Southern-influenced forests with oaks and hickories on lower and drier slopes, including Deciduous forest, some minor pasture 59a. Connecticut 1459 Level to rolling plains with some high 10-1106 (Mt. Holocene alluvium. Quaternary deposits mostly Entisols (Udifluvents, Hadley, Hinckley, Limerick, Mesic / 38-52 135-180 16/35; Mostly central and transition hardwoods. Mixed oak and oak-conifer forests including Urban, suburban, and rural residential, rounded to steep slopes, narrow valleys. 800-2000 bottom deposits of alluvium. -

1967, Al and Frances Randall and Ramona Hammerly

The Mountaineer I L � I The Mountaineer 1968 Cover photo: Mt. Baker from Table Mt. Bob and Ira Spring Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and April by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington, 98111. Clubroom is at 719Y2 Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of North west America; To make expeditions into these regions m fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. EDITORIAL STAFF Betty Manning, Editor, Geraldine Chybinski, Margaret Fickeisen, Kay Oelhizer, Alice Thorn Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111, before November 1, 1968, for consideration. Photographs must be 5x7 glossy prints, bearing caption and photographer's name on back. The Mountaineer Climbing Code A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. On crevassed glaciers, two rope teams are recommended. Carry at all times the clothing, food and equipment necessary. Rope up on all exposed places and for all glacier travel. Keep the party together, and obey the leader or majority rule. Never climb beyond your ability and knowledge. -

Washington Geology, V, 21, No. 2, July 1993

WASHINGTON GEOLOGY Washington Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Earth Resources Vol. 21, No. 2, July 1993 , Mount Baker volcano from the northeast. Bagley Lakes, in the foreground, are on a Pleistocene recessional moraine that is now the parking lot for Mount Baker Ski Area. Just below Sherman Peak, an erosional remnant on the left skyline, is Boulder Glacier. Park and Rainbow Glaciers share the area below the main summit (Grant Peak, 10,778 ft) . Boulder, Park, and Rainbow Glaciers drain into Baker Lake, which is out of the photo on the left. Mazama Glacier forms under the ridge that extends to Hadley Peak on the right. (See related article, p. 3 and Fig. 2, p. 5.) Table Mountain, the flat area just above and to the right of center, is a truncated lava flow. Lincoln Peak is just visible over the right shoulder of Mount Baker. Photo taken in 1964. In This Issue: Current behavior of glaciers in the North Cascades and its effect on regional water supplies, p. 3; Radon potential of Washington, p. 11; Washington areas selected for water quality assessment, p. 14; The changing role of cartogra phy in OGER-Plugging into the Geographic Information System, p. 15; Additions to the library, p. 16. Revised State Surface Minin!Jf Act-1993 by Raymond Lasmanls WASHINGTON The 1993 regular session of the 53rd Le:gislature passed a major revision of the surface mine reclamation act as En GEOLOGY grossed Second Substitute Senate Bill No. 5502. The new law takes effect on July 1, 1993. Both environmental groups and surface miners testified in favor of the act. -

The Genus Vaccinium in North America

Agriculture Canada The Genus Vaccinium 630 . 4 C212 P 1828 North America 1988 c.2 Agriculture aid Agri-Food Canada/ ^ Agnculturo ^^In^iikQ Canada V ^njaian Agriculture Library Brbliotheque Canadienno de taricakun otur #<4*4 /EWHE D* V /^ AgricultureandAgri-FoodCanada/ '%' Agrrtur^'AgrntataireCanada ^M'an *> Agriculture Library v^^pttawa, Ontano K1A 0C5 ^- ^^f ^ ^OlfWNE D£ W| The Genus Vaccinium in North America S.P.VanderKloet Biology Department Acadia University Wolfville, Nova Scotia Research Branch Agriculture Canada Publication 1828 1988 'Minister of Suppl) andS Canada ivhh .\\ ailabla in Canada through Authorized Hook nta ami other books! or by mail from Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Services Canada Ottawa, Canada K1A0S9 Catalogue No.: A43-1828/1988E ISBN: 0-660-13037-8 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data VanderKloet,S. P. The genus Vaccinium in North America (Publication / Research Branch, Agriculture Canada; 1828) Bibliography: Cat. No.: A43-1828/1988E ISBN: 0-660-13037-8 I. Vaccinium — North America. 2. Vaccinium — North America — Classification. I. Title. II. Canada. Agriculture Canada. Research Branch. III. Series: Publication (Canada. Agriculture Canada). English ; 1828. QK495.E68V3 1988 583'.62 C88-099206-9 Cover illustration Vaccinium oualifolium Smith; watercolor by Lesley R. Bohm. Contract Editor Molly Wolf Staff Editors Sharon Rudnitski Frances Smith ForC.M.Rae Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada - Agriculture et Agroalimentaire Canada http://www.archive.org/details/genusvacciniuminOOvand -

Mining Index To

MINING INDEX TO HENDERSON, HOLLISTER, AND CANFIELD HISTORIES DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY WESTERN HISTORY DEPARTMENT Typed and edited by Rita Torres February, 1995 MINING INDEX to Henderson, Hollister, and Canfield mining histories. Names of mines, mining companies, mining districts, lodes, veins, claims, and tunnels are indexed with page number. Call numbers are as follows: Henderson, Charles. Mining in Colorado; a history of discovery, development and production. C622.09 H38m Canfield, John. Mines and mining men of Colorado, historical, descriptive and pictorial; an account of the principal producing mines of gold and silver, the bonanza kings and successful prospectors, the picturesque camps and thriving cities of the Rocky Mountain region. C978.86 C162mi Hollister, Orvando. The mines of Colorado. C622.09 H72m A M W Abe Lincoln mine p.155c, 156b, 158a, 159b, p.57b 160b Henderson Henderson Adams & Stahl A M W mill p.230d p.160b Henderson Henderson Adams & Twibell A Y & Minnie p.232b p.23b Henderson Canfield Adams district A Y & Minnie mill p.319 p.42d, 158b, 160b Hollister Henderson Adams mill A Y & Minnie mines p.42d, 157b, 163b,c, 164b p.148a, 149d, 153a,c,d, 156c, Henderson 161d Henderson Adams mine p.43a, 153a, 156b, 158a A Y mine, Leadville Henderson p.42a, 139d, 141d, 147c, 143b, 144b Adams mining co. Henderson p.139c, 141c, 143a Henderson 1 Adelaide smelter Alabama mine p.11a p.49a Henderson Henderson Adelia lode Alamakee mine p.335 p.40b, 105c Hollister Henderson Adeline lode Alaska mine, Poughkeepsie gulch p.211 p.49a, 182c Hollister Henderson Adrian gold mining co. -

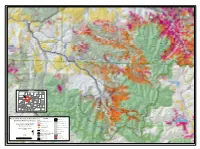

Forest Wide Hazardous Tree Removal and Fuels Reduction Project

107°0'0"W VAIL k GYPSUM B e 6 u 6 N 1 k 2 k 1 h 2 e . e 6 . .1 I- 1 o 8 70 e c f 7 . r 0 e 2 2 §¨¦ e l 1 0 f 2 u 1 0 3 2 N 4 r r 0 1 e VailVail . 3 W . 8 . 1 85 3 Edwards 70 1 C 1 a C 1 .1 C 8 2 h N 1 G 7 . 7 0 m y 1 k r 8 §¨¦ l 2 m 1 e c . .E 9 . 6 z W A T m k 1 5 u C 0 .1 u 5 z i 6. e s 0 C i 1 B a -7 k s 3 2 .3 e e r I ee o C r a 1 F G Carterville h r e 9. 1 6 r g 1 N 9 g 8 r e 8 r y P e G o e u l Avon n C 9 N C r e n 5 ch w i r 8 .k2 0 N n D k 1 n 70 a tt e 9 6 6 8 G . c 7 o h 18 1 §¨¦ r I-7 o ra West Vail .1 1 y 4 u h 0 1 0. n lc 7 l D .W N T 7 39 . 71 . 1 a u 1 ch W C k 0 C d . 2 e . r e 1 e 1 C st G e e . r 7 A Red Hill R 3 9 k n s e 5 6 7 a t 2 . -

The Waterspout on the Cheviots—Broken Peat-Bed. British Rainfall, 1893

THE WATERSPOUT ON THE CHEVIOTS—BROKEN PEAT-BED. BRITISH RAINFALL, 1893. LONDON: C SHIELD, PRINTER, 4, LEETE STREET, CHELSEA ; & LANCELOT PLACE, BIlOMVTON. 1894. BRITISH RAINFALL, 1893. THE DISTRIBUTION OF UAIN OVEE THE BRITISH ISLES, DURING THE YE1R 1893, AS OBSERVED AT NEARLY 3000 STATIONS IN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND, WITH ARTICLES UPON VARIOUS BRANCHES OF RAINFALL WORK. COMPILED BY G. J. SYMONS, F.R.S., CHEVALIER DE LA LTSGION D'HONNEUR, Secretary Royal Meteorological Society; Membredu Conseil Societe Meteorologique de France. Member Scottish Meteorological Society ; Korrespondirendes Mitglied der Deutschen Meteorologischen Gesellschaft; Registrar of Sanitary Institute ; Fellow Royal Colonial Institute ; Membre correspondant etranger Soc. Royale de Medecine Publique de JleJgique, Socio correspondiente Sociedad Cientifica Antonio Alzate, Mexico, $c. AND H. SOWERBY WALLIS, F.R.MetSoc. LONDON: EDWARD STANFORD, COCKSPUR STREET, S.W 1894. CONTENTS. PAGE PREFACE ... ... ... .. ... ... ... .. ... ... ... .. ... ... 7 REPORT—PUBLICATIONS—OLD OBSERVATIONS—FIXANCE ... ... ... .. 8 THE WATERSPOUT (OR CLOUD BURST) ON THE CHEVIOTS ... ... ... ... 14 HEAVY FALLS OF RAIN AT CAMDEN SQUARE, 1858—1894 ... ... ... ... 18 EXPERIMENTS ox EVAPORATION AT SOUTHAMPTON WATER WORKS AND AT CAMDEN SQUARE ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. ... ... 23 COMPARISON OF GERMAN AND ENGLISH RAIN GAUGES AND OF MR. SIDEBOTTOM'S Sxo\v GAUGE ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 27 RAINFALL AT THE ROYAL OBSERVATORY, GREENWICH ... ... ... ... 30 THE STAFF OF OBSERVERS... ... ..