Diglossia in Arabica Comparative Study of the Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of Diglossic Code Switching Situations: a Sociolinguistic Interpretation

European Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 2 No. 4, 2014 ISSN 2056-5429 ASPECTS OF DIGLOSSIC CODE SWITCHING SITUATIONS: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INTERPRETATION Hayet BAGUI Naama University ALGERIA ABSTRACT Code switching, a type of discourse that occurs as a natural outcome of language contact, has attracted linguists‟ attention and been studied from a variety of perspectives. Scholars do not seem to share a single definition of the concept, and this is perhaps inevitable, given the different concerns of formal linguists, psycholinguists, sociolinguists, anthropo-linguists and so forth. Whatever the definitions are, it is obvious that anyone who speaks more than one code switches back and forth between these codes or mixes them according to certain circumstances. CS can occur in a monolingual community, or in a plurilingual speech collectivity. In a monolingual context, Code switching relates to a diglossic situation where speakers make use of two varieties for well-defined set of functions: a H variety, generally the standard, for formal contexts, and a L variety typically for everyday informal communicative acts. In addition to alternation between H and L varieties, speakers may also switch between the dialects available to them in that community via a process of CS. In such a case, i.e. monolingual context, CS is classified as being ‘internal’, as the switch occurs between different varieties of the same language. In a multilingual community, the switch is between two or more linguistic systems. This is referred to as „external‟ code switching. Hence, the present research work includes a classification of the phenomenon in terms of „internal‟ code switching which is of a diglossic nation as well as „external‟ one with denotes a kind of extended diglossic contexts. -

Arabic Sociolinguistics: Topics in Diglossia, Gender, Identity, And

Arabic Sociolinguistics Arabic Sociolinguistics Reem Bassiouney Edinburgh University Press © Reem Bassiouney, 2009 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in ll/13pt Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and East bourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 2373 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 2374 7 (paperback) The right ofReem Bassiouney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements viii List of charts, maps and tables x List of abbreviations xii Conventions used in this book xiv Introduction 1 1. Diglossia and dialect groups in the Arab world 9 1.1 Diglossia 10 1.1.1 Anoverviewofthestudyofdiglossia 10 1.1.2 Theories that explain diglossia in terms oflevels 14 1.1.3 The idea ofEducated Spoken Arabic 16 1.2 Dialects/varieties in the Arab world 18 1.2. 1 The concept ofprestige as different from that ofstandard 18 1.2.2 Groups ofdialects in the Arab world 19 1.3 Conclusion 26 2. Code-switching 28 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Problem of terminology: code-switching and code-mixing 30 2.3 Code-switching and diglossia 31 2.4 The study of constraints on code-switching in relation to the Arab world 31 2.4. 1 Structural constraints on classic code-switching 31 2.4.2 Structural constraints on diglossic switching 42 2.5 Motivations for code-switching 59 2. -

Abstract Language Variation and Gender in Egypt; Evidence from Talk Shows

Abstract Language variation and gender in Egypt; Evidence from talk shows. Dr. Reem Bassiouney: Assistant Professor of Arabic linguistics at Georgetown University, Washington DC. In the Arabic speaking world there is a difference between a ‘prestige variety’ and a ‘standard’ one. There is also a diglossic situation. Diglossia is defined by Ferguson (1959) as a language situation in which two languages or varieties exist side by side - each with a different function. In the Arab world there is a standard Arabic which is used in education and sometimes in formal occasions, and there are also the different vernaculars of different countries (cf. Bassiouney 2006). Many linguistic studies in the Arab world have shown that for most people there is a prestige vernacular, the identity of which depends on many geographical, political and social factors within each country. In Egypt for example, for non-Cairene it is Cairene. It is usually the Urban dialect of the big cities. This linguistic situation does not exist in many Western societies, with the consequence that at a first glance the results reached by some Western linguists concerning language and gender seem to contradict those reached by some linguists in the Arab world. For example, Labov (1972) concludes that women use a more prestigious form of language. Gall (1978-79) in her study of a village in Austria found that women use the prestigious variety of German more than men as a form of securing their position in society. The fact that linguists like Daher (1999) may claim that specific women of a specific background may not use some standard features of language does not contradict the findings of Labov and others, since women may still use the prestige form of language which, as was said earlier, is different from the standard one. -

Diglossia and Beyond

Chapter 9 Diglossia and Beyond Jürgen Jaspers Introduction Diglossia in simple terms refers to the use of two varieties in the same society for com- plementary purposes.1 As unassuming as this may sound, the concept can undoubtedly be called one of the grandes dames or, depending on your critical disposition, monstres sacrés of the sociolinguistic stage, against which new, would-be contenders still have to prove themselves, if they ever manage to emulate its success. For although the con- cept may increasingly be found old- school, politically conservative, and leaving some- thing to be desired in terms of its descriptive and explanatory adequacy, diglossia is still a widely acclaimed celebrity if you keep score of its occurrence in sociolinguistic, language- pedagogical, and linguistic anthropological work. What could be the reasons for this popularity? One obvious reason is that diglossia has been attracting a fair share of criticism in each of these disciplines. But another is certainly that diglossia practicably, in a single term, portrays the sometimes quite wide- spread and in a number of occasions astoundingly long- standing divisions of labor that obtain between the different varieties, registers, or styles that people produce and recog- nize. Indeed, diglossia alludes to two of the most basic, and therefore also most fascinat- ing, sociolinguistic findings— namely, that people talk and write differently even in the most homogeneous of communities, and that they do so in principled ways that matter to them so much that those who fail to observe these principles have to deal with the consequences (cf. Woolard, 1985: 738). -

Sociolinguistic Situation of Kurdish in Turkey: Sociopolitical Factors and Language Use Patterns

DOI 10.1515/ijsl-2012-0053 IJSL 2012; 217: 151 – 180 Ergin Öpengin Sociolinguistic situation of Kurdish in Turkey: Sociopolitical factors and language use patterns Abstract: This article aims at exploring the minority status of Kurdish language in Turkey. It asks two main questions: (1) In what ways have state policies and socio- historical conditions influenced the evolution of linguistic behavior of Kurdish speakers? (2) What are the mechanisms through which language maintenance versus language shift tendencies operate in the speech community? The article discusses the objective dimensions of the language situation in the Kurdish re- gion of Turkey. It then presents an account of daily language practices and perceptions of Kurdish speakers. It shows that language use and choice are sig- nificantly related to variables such as age, gender, education level, rural versus urban dwelling and the overall socio-cultural and political contexts of such uses and choices. The article further indicates that although the general tendency is to follow the functional separation of languages, the language situation in this con- text is not an example of stable diglossia, as Turkish exerts its increasing pres- ence in low domains whereas Kurdish, by contrast, has started to infringe into high domains like media and institutions. The article concludes that the preva- lent community bilingualism evolves to the detriment of Kurdish, leading to a shift-oriented linguistic situation for Kurdish. Keywords: Kurdish; Turkey; diglossia; language maintenance; language shift Ergin Öpengin: Lacito CNRS, Université Paris III & Bamberg University. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction Kurdish in Turkey is the language of a large population of about 15–20 million speakers. -

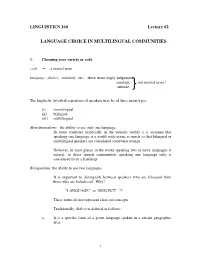

LINGUISTICS 160 Lecture #2

LINGUISTICS 160 Lecture #2 LANGUAGE CHOICE IN MULTILINGUAL COMMUNITIES 1. Choosing your variety or code code → a neutral term language, dialect, standard, etc.: these terms imply judgement, emotion, not neutral terms! attitude The linguistic (=verbal) repertoire of speakers may be of three main types: (i) monolingual (ii) bilingual (iii) multilingual Monolingualism: the ability to use only one language. In some countries (especially in the western world) it is assumed that speaking one language is a world-wide norm, so much so that bilingual or multilingual speakers are considered somewhat strange. However, in most places in the world speaking two or more languages is natural; in those speech communities speaking one language only is considered to be a handicap. Bilingualism: the ability to use two languages. It is important to distinguish between speakers who are bilingual from those who are bidialectal. Why? “LANGUAGE” or “DIALECT” ?? These terms do not represent clear-cut concepts. Traditionally, dialect is defined as follows: a. It is a specific form of a given language spoken in a certain geographic area. 1 b. It differs substantially from the standard of that language (pronunciation, grammatical construction, idiomatic usage of words, etc.). c. It is not sufficiently distinct to be regarded as a different language. Problem: It has often been said that language is a collection of mutually intelligible dialects. ‘mutually intelligible’ → this is a linguistic criterion. From the speaker’s perspective it is less important, than political and social criteria! Examples: Serbian and Croatian -- languages or dialects? Mandarin and Cantonese -- languages or dialects? Hindi and Urdu -- languages or dialects? Ranamål and Bokmål (see Example 6 on p. -

DIGLOSSIA: an OVERVIEW of the ARABIC SITUATION Morad Alsahafi King Abdulaziz University

International Journal of English Language and Linguistics Research Vol.4, No.4, pp.1-11, June 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) DIGLOSSIA: AN OVERVIEW OF THE ARABIC SITUATION Morad Alsahafi King Abdulaziz University ABSTRACT: One of the most distinctive features of the Arabic language is the existence of diglossia. Arabic largely exists in a diglossic situation, which is manifested through the co- existence of Standard Arabic and Colloquial Arabic (Ferguson, 1959). Any discussion of the language situation in Arabic-speaking communities in the Middle Eastern and North African countries and elsewhere cannot overlook the existence of diglossia. Indeed, Arabic represents the world’s most complicated diglossic situation (Kaye, 2002). This paper provides an overview of diglossia in Arabic. It attempts to outline the meaning of the concept, its different types and its relationship to language stability and change. The overview is meant to be representative rather than comprehensive. KEYWORDS: Diglossia, Standard Arabic, Colloquial Arabic, Language variety INTRODUCTION Ferguson (1959) and Fishman (1972) are among the major sociolinguists who have developed this notion of functional differentiation of languages or language varieties in order to explain patterns of language use and choice. Ferguson (1959) first introduced the notion of diglossia to describe the functional distribution of two genetically related varieties in different settings. Since then, the notion of diglossia has been developed and become widely and usefully employed to describe patterns of language use and choice in diglossic and bi/multilingual communities in different places around the world. The following section provides an overview of diglossia, outlining the meaning of the concept, its different types and its relationship to language stability and change. -

Bilingualism, Diglossia and Language Planning : Three Major Topics of Socio- Linguistic Concern in Belgium ·

Bilingualism, Diglossia and Language Planning : Three Major Topics of Socio linguistic Concern in Belgium · door ROLAND Wll.LEMYNS The aim of this lecture is to introduce in a nutshell the linguistic or sociolinguistic problems to be encountered in Belgium and to discuss the ways they are currently being investigated by ( socio )linguists. Although one might theoretically distinguish between domestic and crossnational linguistic problems in Belgium, none are purely domestic since they are either in origin and/ or in their further de velopment, related to the fact that the different language groups in Belgium use a language which is not only used elswhere, hut is moreover used immediately across the national border. None of these language groups (Dutch, French and German) constitutes the centre of gravity of the evolution of these languages. Although I would not go as far as Haugen who says that every language in Belgium "belongs to its neighbours" (Haugen 1966: 928) it is obvious that the fact of speaking a so-called exoglottic language determines linguistic fate as well as intem;lation. Before turning to the linguistic situation of the Dutch speaking part of the country which will bear the main focus of my lecture, I should give you some basic information concerning the part played by language issues in Belgian politica! life, as wel! as the linguistic facts which account for it. I should like to start with a quotation from my Brussels collegue Hugo Baetens Beardsmore, a distinguis hed scholar of bilingualism : , , Language is the most explosive force in Belgian political life '' he says , , .. .language loyalties override all other questions that form part of the body politie of Belgian life, uniting conflicting ideologies, drawing to gether social classes with contradictory interests, producing bedfellows who without the common bond of a mutually shared language would have little contact" (Baetens Beardsmore 1980: 145 ). -

A Study on the Impact of Arabic Diglossia on L2 Learners of Arabic: Examining Motivation and Perception

Arab World English Journal (December, 2017) Theses / Dissertation (ID 190) Pp.1-70 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/th.190 Author: Maha Abdelrahman Al Hariri Al Zahrani Thesis Title: A Study on the Impact of Arabic Diglossia on L2 learners of Arabic: Examining Motivation and Perception. Subject/major: Linguistics (Bilingualism). Institution: School of Linguistics, Bangor University Wales, UK Degree: Master in Linguistics. Year of award: 2013 Supervisor: Dr. Marco Tamburelli Keywords: Diglossia, colloquial Arabic, modern standard Arabic, motivation, perception Abstract: One of the most distinctive features of the Arabic language is the occurrence of diglossia (Al- Batal, 1995). Diglossia involves the use of two varieties of the same language by the same society for different functions. The principle objective of this independent inquiry is to study the impact of Arabic diglossia on L2 learners of Arabic studying this language in the native Arab environment i.e. Saudi Arabia, which is the centre of MSA variety of Arabic. This study also aimed at understanding the effect of awareness about Arabic diglossia on the motivation of L2 learners. Qualitative methodology has been used to gain an in-depth view of the perceptions and the motivation level of L2 learners in two language institutes in Saudi Arabia. The primary data has been collected through self-administered questionnaires from 15 participants studying Arabic at various stages of language learning in the selected language institutes. The secondary data has been taken from various past researchers and literary works related to the topic of this dissertation. It has been found that the L2 learners of Arabic are generally aware of the Arabic diglossia and understand the functional differences between CA and MSA, but this situation doesn’t significantly affect their learning progress as assessed by their academic learning progress before and after attending the language centre and their willingness to continue learning the Arabic language. -

LANGUAGES and LINGUISTICS Umber 15 • 1962 Edited by E

Monograph Series on LANGUAGES and LINGUISTICS umber 15 • 1962 edited by E. D. Woodworth and R. J. Di Pietrc Raimonde Dallaire William Gage Paul L Garvin Paul M. Postal Eric P. Hamp, Moderator The Transformation Theory: Advantages and Disadvantages A. Richard Diebold, Jr. Code-Switching in Greek-English Bilingual Speech Einar Haugen Schizoglossia and the Linguistic Norm Colman L O'Huallachain, O.F.M. Bilingualism in Education in Ireland Norman A. McQuown Indian and Ladino Bilingualism: Sociocultural Contrasts in Chiapas, Mexico Fred W. Householder, Jr. Greek Diglossia William G. Moulton What Standard for Diglossia? The Case of German Switzerland William A. Stewart Functional Distribution of Creole and French in Haiti Charles A. Ferguson Problems of Teaching Languages with Diglossia KRAUS REPRINT CO. New York GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY 1971 INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Copyright © 1963 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY PRESS THE INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 63-21238 Reprinted with the permission of the original publisher KRAUS REPRINT CO. A U.S. Division of Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited New York 1971 Printed in U.S.A. REPORT OF THE THIRTEENTH ANNUAL ROUND TABLE MEETING ON LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE STUDIES Elisabeth 3? Wobdworth Editor Robert J. DiJPietro Associate 5 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY PRESS Washington, D. C. 20007 Copyright © 1963 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY PRESS THE INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 63-21238 time to time the Institute of Languages and Linguistics, George- town University, 'publishes manu- scripts intended to contribute to the discipline of linguistics and to the study and teaching of languages. -

Diglossia Among Students: the Problem and Treatment

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.32, 2015 Diglossia among Students: The Problem and Treatment Dr. Qasem Nawaf Al- Brri Al- Albait University Dr. Mohammad Fawzy Ahmed Bani-Yaseen Al- Balqa Applied University- Ajloun University College- Basic Sience Department, Arabic Language Curriculum and Instruction Dr. Mohammad Akram Al-Zu’bi English Department, Ajloun University College, AL-Balqa Applied University, Jordan Dr. Mesfer Saud Al-Hersh Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Arabic Language Curriculum and Instruction Abstract This study aims at identifying the concept of diglossia, its causes and methods of treatment, and its negative effects. The researchers used the descriptive method. The study revealed the following most important results: Firstly, the reason for language diglossia is contact between languages and emergence of new other languages or dialects which leads to a losing some of their original characteristics and qualities and the different environments within the same society that has a role in the emergence of diglossia. Secondly, it causes moving away from the mother tongue. Thirdly, the study also found that classical Arabic is the strongest ligament, which brings the peoples of the Arab nation together. Fourthly, diglossia can be reduced by simplifying classical rules of Arabic; facilitating the teaching methods and by paying attention to basic Arabic, which is supposed to be the focus of education for the emerging of mother tongue. Keywords: Diglossia, classical language, slang language 1. Introduction The official language is used in schools, colleges and universities and all different subjects at all stages of education are studied by official language. -

A Moving Target: Literacy Development in Situations of Diglossia and Bilingualism

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Languages, Literatures and Cultures Faculty Scholarship Languages, Literatures & Cultures 9-2015 A moving target: literacy development in situations of diglossia and bilingualism Lotfi Sayahi University at Albany, State University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/cas_llc_scholar Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Sayahi, Lotfi, A" moving target: literacy development in situations of diglossia and bilingualism" (2015). Languages, Literatures and Cultures Faculty Scholarship. 13. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/cas_llc_scholar/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages, Literatures & Cultures at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures and Cultures Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arab Journal of Applied Linguistics A moving target: literacy Vol. 1, No. 1, September, 2015, 1-18 © The Author(s) development in situations of http://www.tjaling.org diglossia and bilingualism 1 Lotfi Sayahi University at Albany, State University of New York Abstract The present paper analyzes the challenges of literacy development in cases of classical diglossia and bilingualism. The main argument is that the diverse levels of proficiency in the varieties present in a given linguistic market have implications