The Redwall Limestone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ron Blakey, Publications (Does Not Include Abstracts)

Ron Blakey, Publications (does not include abstracts) The publications listed below were mainly produced during my tenure as a member of the Geology Department at Northern Arizona University. Those after 2009 represent ongoing research as Professor Emeritus. (PDF) – A PDF is available for this paper. Send me an email and I'll attach to return email Blakey, R.C., 1973, Stratigraphy and origin of the Moenkopi Formation of southeastern Utah: Mountain Geologist, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1 17. Blakey, R.C., 1974, Stratigraphic and depositional analysis of the Moenkopi Formation, Southeastern Utah: Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 104, 81 p. Blakey, R.C., 1977, Petroliferous lithosomes in the Moenkopi Formation, Southern Utah: Utah Geology, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 67 84. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Oil impregnated carbonate rocks of the Timpoweap Member Moenkopi Formation, Hurricane Cliffs area, Utah and Arizona: Utah Geology, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 45 54. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Stratigraphy of the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian Permian), Mogollon Rim, Arizona: in Carboniferous Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon Country, northern Arizona and southern Nevada, Field Trip No. 13, Ninth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, p. 89 109. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Lower Permian stratigraphy of the southern Colorado Plateau: in Four Corners Geological Society, Guidebook to the Permian of the Colorado Plateau, p. 115 129. (PDF) Blakey, R.C., 1980, Pennsylvanian and Early Permian paleogeography, southern Colorado Plateau and vicinity: in Paleozoic Paleogeography of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, p. 239 258. Blakey, R.C., Peterson, F., Caputo, M.V., Geesaman, R., and Voorhees, B., 1983, Paleogeography of Middle Jurassic continental, shoreline, and shallow marine sedimentation, southern Utah: Mesozoic PaleogeogÂraphy of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section of Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists (Symposium), p. -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Structural Geology and Hydrogeology of the Grandview Breccia Pipe, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona M

Structural Geology and Hydrogeology of the Grandview Breccia Pipe, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona M. Alter, R. Grant, P. Williams & D. Sherratt Grandview breccia pipe on Horseshoe Mesa, Grand Canyon, Arizona March 2016 CONTRIBUTED REPORT CR-16-B Arizona Geological Survey www.azgs.az.gov | repository.azgs.az.gov Arizona Geological Survey M. Lee Allison, State Geologist and Director Manuscript approved for publication in March 2016 Printed by the Arizona Geological Survey All rights reserved For an electronic copy of this publication: www.repository.azgs.az.gov Printed copies are on sale at the Arizona Experience Store 416 W. Congress, Tucson, AZ 85701 (520.770.3500) For information on the mission, objectives or geologic products of the Arizona Geological Survey visit www.azgs.az.gov. This publication was prepared by an agency of the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona, or any agency thereof, or any of their employees, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report. Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the State of Arizona. Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Report series provides non-AZGS authors with a forum for publishing documents concerning Arizona geology. While review comments may have been incorpo- rated, this document does not necessarily conform to AZGS technical, editorial, or policy standards. The Arizona Geological Survey issues no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding the suitability of this product for a particular use. -

Grand Canyon

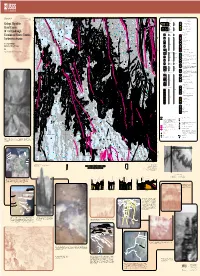

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Subsurface Geologic Plates of Eastern Arizona and Western New Mexico

Implications of Live Oil Shows in an Eastern Arizona Geothermal Test (1 Alpine-Federal) by Steven L. Rauzi Oil and Gas Program Administrator Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 94-1 Version 2.0 June, 2009 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 INTRODUCTION The 1 Alpine-Federal geothermal test, at an elevation of 8,556 feet in eastern Arizona, was drilled by the Arizona Department of Commerce and U.S. Department of Energy to obtain information about the hot-dry-rock potential of Precambrian rocks in the Alpine-Nutrioso area, a region of extensive basaltic volcanism in southern Apache County. The hole reached total depth of 4,505 feet in August 1993. Temperature measurements were taken through October 1993 when final temperature, gamma ray, and neutron logs were run. The Alpine-Federal hole is located just east of U.S. Highway 180/191 (old 180/666) at the divide between Alpine and Nutrioso, in sec. 23, T. 6 N., R. 30 E., in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest (Fig. 1). The town of Alpine is about 6 miles south of the wellsite and the Arizona-New Mexico state line is about 6 miles east. The basaltic Springerville volcanic field is just north of the wellsite (Crumpler, L.S., Aubele, J.C., and Condit, C.D., 1994). Although volcanic rocks of middle Miocene to Oligocene age (Reynolds, 1988) are widespread in the region, erosion has removed them from the main valleys between Alpine and Nutrioso. As a result, the 1 Alpine-Federal was spudded in sedimentary strata of Oligocene to Eocene age (Reynolds, 1988). -

Grand Canyon Archaeological Site

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY For Colorado River Commercial Operators This etiquette policy was developed as a preservation tool to protect archaeological sites along the Colorado River. This policy classifies all known archaeological sites into one of four classes and helps direct visitors to sites that can withstand visitation and to minimize impacts to those that cannot. Commercially guided groups may visit Class I and Class II sites; however, inappropriate behaviors and activities on any archaeological site is a violation of federal law and Commercial Operating Requirements. Class III sites are not appropriate for visitation. National Park Service employees and Commercial Operators are prohibited from disclosing the location and nature of Class III archaeological sites. If clients encounter archaeological sites in the backcountry, guides should take the opportunity to talk about ancestral use of the Canyon, discuss the challenges faced in protecting archaeological resources in remote places, and reaffirm Leave No Trace practices. These include observing from afar, discouraging clients from collecting site coordinates and posting photographs and maps with location descriptions on social media. Class IV archaeological sites are closed to visitation; they are listed on Page 2 of this document. Commercial guides may share the list of Class I, Class II and Class IV sites with clients. It is the responsibility of individual Commercial Operators to disseminate site etiquette information to all company employees and to ensure that their guides are teaching this information to all clients prior to visiting archaeological sites. Class I Archaeological Sites: Class I sites have been Class II Archaeological Sites: Class II sites are more managed specifically to withstand greater volumes of vulnerable to visitor impacts than Class I sites. -

NPS History Elibrary

STATE: fnT 1977?6 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ^uct. iv//; NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arizona COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTC )RIC PLACES Coconino INVENTORY - NOMINATIO N FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPER TIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries • complete applic able sections) JUL a 1974 COMMON: Grandview Mine (H.S.-ll AND/OR HISTORIC: -' ' Last Chance Mine; Canyon Copper Company Mine STREET AND NUMBER: Grand Canyon National Park, T30N, Rl$ G & SR EM CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Grand Canyon Third STATE: CODE COUNTY: CODE Arizona OU Coconino 005 IPBIiiM^S^iPM^^PIiiPMP ii:|ii:j:;:|i|:|:;^ lllllllillllllillllllllililllllilllllllllillll STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check£AJ*?2 One)R\ OWNERSHIP J>IAIU=> T0 THE p UBUC [jg District CD Building £] Public Public Acquisition: I | Occupied Yes: CD Site CD Structure | | Private | | In Process Fjjjl Unoccupied [ | Restricted CD Object CD Both CD Being Considered CD Preservation work [^Unrestricted in progress [~1 No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) CD Agricultural CD Government g£] Park ' CD Transportation CD Comments | | Commercial [~] Industrial CI] Private Residence CD Other (Specifv) CD Educational CDMiltary CI CD Entertainment Q~] Museum Q "3 jSTATE: California3 National Park Service (the land) REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) ^ STREET AND NUMBER: n BOX Western Regional Office ^•50 Golden Gate Ave., 36063 CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE San Francisco California 06 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Coconino County Courthouse SanFrancisc COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

History Along the Trail a Grand(View)

Canyon VIEWS Volume XXIIII, No. 2 JULY 2017 History Along the Trail A Grand(view) Adventure Black and White and Hidden from Sight The official nonprofit partner of Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon Association Canyon Views is published by the Grand Canyon FROM THE CEO Association, the National Park Service’s official nonprofit partner, raising private funds to “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning benefit Grand Canyon National Park, operating to find out going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a retail stores and visitor centers within the park and providing premier educational necessity.” opportunities about the natural and cultural history of Grand Canyon. John Muir, the great advocate for preserving our country’s wilderness, You can make a difference at Grand Canyon! wrote those words well over a century ago. Before the advent of For more information about GCA, please visit television. Before the 24-hour news cycle. Before the Internet and www.grandcanyon.org. social media. I can’t imagine what Muir would say about our world Board of Directors: Howard Weiner, Board today. But you can bet his remedy to counteract the “nerve-shaking” Chair; Mark Schiavoni, Board Vice Chair; Lyle we experience—probably 100 times worse now than in his day— Balenquah; Kathryn Campana; Richard Foudy; Eric Fraint; Teresa Gavigan; Robert Hostetler; would be the same. “Get out into nature,” he’d advise. Julie Klapstein; Teresa Kline; Kenneth Lamm; Marsha Sitterley; T. Paul Thomas There is truly nothing that helps us reset like spending time in wild Chief Executive Officer: Susan Schroeder places. -

Chertification of the Redwall Limestone (Mississippian), Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

Chertification of the Redwall limestone (Mississippian), Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hess, Alison Anne Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 09:46:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/558024 CHERTIFICATION OF THE REDWALL LIMESTONE (MISSISSIPPIAN), GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK, ARIZONA by Alison Anne Hess A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES * In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 8 5 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author.