Blowing up the Movies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5131

St. John's College Independent Bi-Weekly • Volume 2, Issue 9 • Friday, February 20,1998 A letter from the Dean...... .....2 Fasching Ball Superstars.... ..... 5 Inside Reichman blurs the lines........3 Movie Reviews................... .... .6 A Letter from the Assistant Reality update................... .....4 J. Bielagus on Darwin........ ....7 Dean..........2 2 The Moon • February 20, 1998 • Volume 2, Issue 9 A Letter to the Community from Assistant Dean Basia Miller To the College Community, views of the two individuals and moved on or even fear in the college community. The Dean and I want to let you all know to include a number of other people from The Dean and I have been particularly about an event that has required our investi- each side whom we called upon or who aware of our responsibility to let you know gation over the past few days and how it came forward on their own. promptly as many of the details as possible was concluded. Writing an open letter to However, before the college concluded in order to squelch any rumors and allay any the campus community seems the quickest its investigation, the male student decided to anxieties you may have had. and most complete way to do this. withdraw, in part for financial reasons. His It disturbs the whole community to hear As you may or may not have known, one voluntary withdrawal from the college rumors and to be caught up in puzzling over of our female students allegedly suffered a meant that our investigation was terminated how this could happen on our campus. -

Johnnie to Kei-Fung's

JOHNNIE TO KEI-FUNG’S PTU Michael Ingham Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2009 Michael Ingham ISBN 978-962-209-919-7 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Pre-Press Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface vii Acknowledgements xi 1 Introducing the Film; Introducing Johnnie — 1 ‘One of Our Own’ 2 ‘Into the Perilous Night’ — Police and Gangsters 35 in the Hong Kong Mean Streets 3 ‘Expect the Unexpected’ — PTU’s Narrative and Aesthetics 65 4 The Coda: What’s the Story? — Morning Glory! 107 Notes 127 Appendix 131 Credits 143 Bibliography 147 ●1 Introducing the Film; Introducing Johnnie — ‘One of Our Own’ ‘It is not enough to think about Hong Kong cinema simply in terms of a tight commercial space occasionally opened up by individual talent, on the model of auteurs in Hollywood. The situation is both more interesting and more complicated.’ — Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong Culture and the Politics of Disappearance ‘Yet many of Hong Kong’s most accomplished fi lms were made in the years after the 1993 downturn. Directors had become more sophisticated, and perhaps fi nancial desperation freed them to experiment … The golden age is over; like most local cinemas, Hong Kong’s will probably consist of a small annual output and a handful of fi lms of artistic interest. -

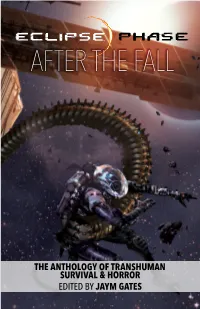

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

The Life Artistic: July / August 2016 Wes Anderson + Mark Mothersbaugh

11610 EUCLID AEUE, CLEELAD, 44106 THE LIFE ARTISTIC: JULY / AUGUST 2016 WES ANDERSON + MARK MOTHERSBAUGH July and August 2016 programming has been generously sponsored by TE LIFE AUATIC ... AUATIC TE LIFE 4 FILMS! ALL 35MM PRINTS! JULY 7-29, 2016 THE CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF ART CINEMATHEQUE 11610 EUCLID AVENUE, UNIVERSITY CIRCLE, CLEVELAND OHIO 44106 The Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque is Cleveland’s alternative film theater. Founded in 1986, the Cinematheque presents movies in CIA’s Peter B. Lewis Theater at 11610 Euclid Avenue in the Uptown district of University Circle. This new, 300-seat theater is equipped with a 4K digital cinema projector, two 35mm film projectors, and 7.1 Dolby Digital sound. Free, lighted parking for filmgoers is currently available in two CIA lots located off E. 117th Street: Lot 73 and the Annex Lot. (Those requiring disability park- ing should use Lot 73.) Enter the building through Entrance C (which faces E. 117th) or Entrance E (which faces E. 115th). Unless noted, admission to each screening is $10; Cinematheque members, CIA and Cleveland State University I.D. holders, and those age 25 & under $7. A second film on LOCATION OF THE the same day generally costs $7. For further information, visit PETER B. LEWIS THEATER (PBL) cia.edu/cinematheque, call (216) 421-7450, or send an email BLACK IL to [email protected]. Smoking is not permitted in the Institute. TH EACH FILM $10 • MEMBERS, CIA, AGE 25 & UNDER $7 • ADDITIONAL FILM ON SAME DAY $7 OUR 30 ANNIVERSARY! FREE LIGHTED PARKING • TEL 216.421.7450 • CIA.EDU/CINEMATHEQUE BLOOD SIMPLE TIKKU INGTON TE LIFE ATISTIC: C I N E M A T A L K ES ADES AK TESBAU ul 72 (4 lms) obody creates cinematic universes like es Anderson. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Spectre, Connoting a Denied That This Was a Reference to the Earlier Films

Key Terms and Consider INTERTEXTUALITY Consider NARRATIVE conventions The white tuxedo intertextually references earlier Bond Behind Bond, image of a man wearing a skeleton mask and films (previous Bonds, including Roger Moore, have worn bone design on his jacket. Skeleton has connotations of Central image, protag- the white tuxedo, however this poster specifically refer- death and danger and the mask is covering up someone’s onist, hero, villain, title, ences Sean Connery in Goldfinger), providing a sense of identity, someone who wishes to remain hidden, someone star appeal, credit block, familiarity, nostalgia and pleasure to fans who recognise lurking in the shadows. It is quite easy to guess that this char- frame, enigma codes, the link. acter would be Propp’s villain and his mask that is reminis- signify, Long shot, facial Bond films have often deliberately referenced earlier films cent of such holidays as Halloween or Day of the Dead means expression, body lan- in the franchise, for example the ‘Bond girl’ emerging he is Bond’s antagonist and no doubt wants to kill him. This guage, colour, enigma from the sea (Ursula Andress in Dr No and Halle Berry in acts as an enigma code for theaudience as we want to find codes. Die Another Day). Daniel Craig also emerged from the sea out who this character is and why he wants Bond. The skele- in Casino Royale, his first outing as Bond, however it was ton also references the title of the film, Spectre, connoting a denied that this was a reference to the earlier films. ghostly, haunting presence from Bond’s past. -

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines As a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Ralina Joseph, Chair LeiLani Nishime Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication ©Copyright 2013 Jennifer McClearen Running head: AUDIENCE READINGS OF ACTION HEROINES University of Washington Abstract Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen Chair of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Ralina Joseph Department of Communication In this paper, I employ a feminist approach to audience research and examine the individual interviews of 11 undergraduate women who regularly watch and enjoy action heroine films. Participants in the study articulate action heroines as visual metaphors for career and academic success and take pleasure in seeing women succeed against adversity. However, they are reluctant to believe that the female bodies onscreen are physically capable of the action they perform when compared with male counterparts—a belief based on post-feminist assumptions of the limits of female physical abilities and the persistent representations of thin action heroines in film. I argue that post-feminist ideology encourages women to imagine action heroines as successful in intellectual arenas; yet, the ideology simultaneously disciplines action heroine bodies to render them unbelievable as physically powerful women. -

Donnie Yen's Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia

Studies in Media and Communication Vol. 4, No. 2; December 2016 ISSN 2325-8071 E-ISSN 2325-808X Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://smc.redfame.com Remediating the Star Body: Donnie Yen’s Kung Fu Persona in Hypermedia Dorothy Wai-sim Lau1 113/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong Correspondence: Dorothy Wai-sim Lau, 13/F, Hong Kong Baptist University Shek Mun Campus, 8 On Muk Street, Shek Mun, Shatin, Hong Kong. Received: September 18, 2016 Accepted: October 7, 2016 Online Published: October 24, 2016 doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/smc.v4i2.1943 Abstract Latest decades have witnessed the proliferation of digital media in Hong Kong action-based genre films, elevating the graphical display of screen action to new levels. While digital effects are tools to assist the action performance of non-kung fu actors, Dragon Tiger Gate (2006), a comic-turned movie, becomes a case-in-point that it applies digitality to Yen, a celebrated kung fu star who is famed by his genuine martial dexterity. In the framework of remediation, this essay will explore how the digital media intervene of the star construction of Donnie Yen. As Dragon Tiger Gate reveals, technological effects work to refashion and repurpose Yen’s persona by combining digital effects and the kung fu body. While the narrative of pain and injury reveals the attempt of visual immediacy, the hybridized bodily representation evokes awareness more to the act of representing kung fu than to the kung fu itself. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ Tianyi Yao Date Crime and History Intersect: Films of Murder in Contemporary Chinese Wenyi Cinema By Tianyi Yao Master of Arts Film and Media Studies _________________________________________ Matthew Bernstein Advisor _________________________________________ Tanine Allison Committee Member _________________________________________ Timothy Holland Committee Member _________________________________________ Michele Schreiber Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date Crime and History Intersect: Films of Murder in Contemporary Chinese Wenyi Cinema By Tianyi Yao B.A., Trinity College, 2015 Advisor: Matthew Bernstein, M.F.A., Ph.D. An abstract of