Section 3 Habitat Action Plan 4: Wetland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalmarnock Power Station, Riverside

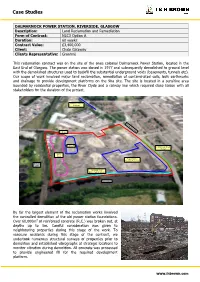

Case Studies DALMARNOCK POWER STATION, RIVERSIDE, GLASGOW Description: Land Reclamation and Remediation Form of Contract: NEC3 Option A Duration: 60 weeks Contract Value: £3,400,000 Client: Clyde Gateway Clients Representative: Grontmij This reclamation contract was on the site of the once colossal Dalmarnock Power Station, located in the East End of Glasgow. The power station was closed in 1977 and subsequently demolished to ground level with the demolished structures used to backfill the substantial underground voids (basements, tunnels etc). Our scope of work involved major land reclamation, remediation of contaminated soils, bulk earthworks and drainage to provide development platforms on the 9ha site. The site is located in a sensitive area bounded by residential properties, the River Clyde and a railway line which required close liaison with all stakeholders for the duration of the project. Dalmarnock Road Drainage Crib wall Borrow Pit Dalmarnock Road Tunnel SUDS Pond Power Station Building Footprint Railway Line Perimeter Wall River Clyde Walkway River Clyde By far the largest element of the reclamation works involved the controlled demolition of the old power station foundations. Over 60,000m3 of reinforced concrete (R.C.) was broken out, at depths up to 5m. Careful consideration was given to neighbouring properties during this stage of the work. To reassure residents during this stage of the contract, we undertook numerous structural surveys of properties prior to demolition and established vibrographs at strategic locations to monitor vibration during demolition. All concrete was processed to provide engineered fill for the required development platform. www.ihbrown.com Case Studies The removal of the substantial perimeter wall included a section which ran parallel with the River Clyde Walkway. -

You May Not Consider a City the Best Place to See Interesting Geology, but Think Again! the City of Glasgow Was, Quite Literally

Glasgow’s Geodiversity K Whitbread1, S Arkley1 and D Craddock2 1British Geological Survey, 2 Glasgow City Council You may not consider a city the best place to see interesting geology, but think again! The city of Glasgow was, quite literally, built on its geology – it may even have been named after one of its rocky features. The geological history of the Glasgow area can be read in the rocks and sediments exposed within the city, from the streams to the buildings and bridges. In 2013 the British Geological Survey Quarrying and building stone conducted a Geodiversity Audit of Sandstones in the Carboniferous sedimentary rocks in the Glasgow the City of Glasgow for Glasgow City area were commonly quarried for Council to identify and describe the building stone. Many former quarries have been infilled, but the best geological features in the city ‘dressed’ faces of worked sandstone, with ‘tool’ marks still area. visible, can be seen in some road cuttings, such as the one below in Here we take you on a tour of some the Upper Limestone Formation at Possil Road. of the sites.... Fossil Forests As well as the local In Carboniferous times, forests of ‘blonde’ sandstone, red Lycopod ‘trees’ grew on a swampy sandstone, granite and river floodplain. In places the stumps other rocks from across of Lycopods, complete with roots, Scotland have been have been preserved. At Fossil Grove, used in many of the a ‘grove’ of fossilised Lycopod stumps historic buildings and was excavated in the Limestone Coal bridges of Glasgow, such Formation during mining. The fossils as in this bridge across were preserved in-situ on their the Kelvin gorge. -

Delivery Plan Update March 2017

Delivery Plan Update March 2017 Table of Contents Overview .................................................................................................... 3 1. Delivering for our customers .............................................................. 5 2. Delivering our investment programme ............................................ 10 3. Providing continuous high quality drinking water ......................... 16 4. Protecting and enhancing the environment ................................... 18 5. Supporting Scotland’s economy and communities ....................... 21 6. Financing our services ...................................................................... 24 7. Scottish Water’s Group Plan and Supporting the Hydro Nation .. 33 2 Overview This update to our Delivery Plan is submitted to Scottish Ministers for approval. It highlights those areas where the content of our original Delivery Plan for the 2015-21 period and the update provided in 2016 have been revised. In our 2015 Delivery Plan we stated that we were determined to deliver significant further improvements for our customers and out-perform our commitments. As we conclude the second year of the 2015-21 period we are on-track to achieve this ambition. Key highlights of our progress so far include: We have successfully driven up customer satisfaction and driven down the number of complaints. As a result our Customer Experience score has risen further this year, and is currently at 85.3, well above our Delivery Plan target of 82.6. Since the start of the regulatory -

Greater Glasgow & the Clyde Valley

What to See & Do 2013-14 Explore: Greater Glasgow & The Clyde Valley Mòr-roinn Ghlaschu & Gleann Chluaidh Stylish City Inspiring Attractions Discover Mackintosh www.visitscotland.com/glasgow Welcome to... Greater Glasgow & The Clyde Valley Mòr-roinn Ghlaschu & Gleann Chluaidh 01 06 08 12 Disclaimer VisitScotland has published this guide in good faith to reflect information submitted to it by the proprietor/managers of the premises listed who have paid for their entries to be included. Although VisitScotland has taken reasonable steps to confirm the information contained in the guide at the time of going to press, it cannot guarantee that the information published is and remains accurate. Accordingly, VisitScotland recommends that all information is checked with the proprietor/manager of the business to ensure that the facilities, cost and all other aspects of the premises are satisfactory. VisitScotland accepts no responsibility for any error or misrepresentation contained in the guide and excludes all liability for loss or damage caused by any reliance placed on the information contained in the guide. VisitScotland also cannot accept any liability for loss caused by the bankruptcy, or liquidation, or insolvency, or cessation of trade of any company, firm or individual contained in this guide. Quality Assurance awards are correct as of December 2012. Rodin’s “The Thinker” For information on accommodation and things to see and do, go to www.visitscotland.com at the Burrell Collection www.visitscotland.com/glasgow Contents 02 Glasgow: Scotland with style 04 Beyond the city 06 Charles Rennie Mackintosh 08 The natural side 10 Explore more 12 Where legends come to life 14 VisitScotland Information Centres 15 Quality Assurance 02 16 Practical information 17 How to read the listings Discover a region that offers exciting possibilities 17 Great days out – Places to Visit 34 Shopping every day. -

City Centre – Carmyle/Newton Farmserving

64 164 364 City Centre – Carmyle/Newton Farm Serving: Tollcross Auchenshuggle Parkhead Bridgeton Newton Farm Bus times from 18 January 2016 Hello and welcome Thanks for choosing to travel with First. We operate an extensive network of services throughout Greater Glasgow that are designed to make your journey as easy as possible. Inside this guide you can discover: • The times we operate this service Pages 6-15 and 18-19 • The route and destinations served Pages 4-5 and 16-17 • Details of best value tickets • Contact details for enquiries and customer services Back Page We hope you enjoy travelling with First. What’s Changed? Service 364 - minor timetable changes before 0930. The 24 hour clock For example: This is used throughout 9.00am is shown as this guide to avoid 0900 confusion between am 2.15pm is shown as and pm time. 1415 10.25pm is shown as 2225 Save money with First First has a wide range of tickets to suit your travelling needs. As well as singles and returns, we have a range of money saving tickets that give unlimited travel at value for money prices. Single – We operate a single flat fare structure in Glasgow, and a simpler four fare structure elsewhere in the network. Buy on the bus from your driver. Return – Valid for travel off-peak making them ideal for customers who know they will only make two trips that day. Buy on the bus from your driver. FirstDay – Unlimited travel in the area of your choice making FirstDay the ideal ticket if you are making more than two trips in a day. -

Glasgow City Council Local Air Quality Management Progress Report

Glasgow City Council Local Air Quality Management Progress Report October 2005 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Background information 6 1.1 Purpose and Role of Progress Report 6 1.2 Air Quality Strategy Objectives & Relevant Public Exposure 6 1.3 Sources of Air Pollution 9 1.4 Summary of Review and Assessment 10 2.0 Summary of monitoring undertaken 12 2.0.1 Automatic Monitoring 12 2.0.2 Non-automatic Monitoring 14 2.1 Monitoring Methodology and Data 17 2.1.1 Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) 17 2.1.2 Particulate Matter (PM10) 29 2.1.3 Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) 38 2.1.4 Carbon Monoxide (CO) 45 2.1.5 Lead 50 2.1.6 Benzene 52 2.1.7 1, 3-Butadiene 55 2.2 New Monitoring Sites 56 2.2.1 Horiba Mobile Unit (Battlefield) 56 2.3 Unregulated Pollutant monitoring 58 2.3.1 Ozone 58 3.0 New Developments 60 3.1 Industrial Processes 60 3.1.1 Part A installations 60 3.1.2 Part B installations 62 3.2 New Transport Developments 62 3.2.1 New/Proposed Road Developments 63 3.2.1.1 Proposed M74 extension 63 3.2.1.2 East End Regeneration Route (EERR) 65 3.2.1.3 Finnieston Street Road Bridge 67 3.2.2 Significant changes to existing roads 68 3.2.2.1 Pre-LRT Project 68 3.3 New Residential, Commercial and Public Developments 69 3.3.1 Queen’s Dock 2 (QD2) Development 69 3.3.2 Pacific Quay 71 3.3.3 Glasgow Harbour Project 72 4.0 Additional Information 74 4.1 Update on the Air Quality Action Plan 74 4.2 New monitoring equipment 80 4.3 Planning applications and policies 80 4.4 Local Transport Plans and Strategies 80 5.0 Conclusions and Recommendations 82 6.0 References & Useful Websites 83 7.0 Further Information 84 2 List of Tables Page No. -

The Neolithic and Early Bronze Age

THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE IN THE FIRTH OF CLYDE ISOBEL MARY HUGHES VOLUMEI Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph. D. Department of Archaeology The University of Glasgow October 1987 0 Isobel M Hughes, 1987. In memory of my mother, and of my father - John Gervase Riddell M. A., D. D., one time Professor of Divinity, University of Glasgow. 7727 LJ r'- I 1GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY i CONTENTS i " VOLUME I LIST OF TABLES xii LIST OF FIGURES xvi LIST OF PLATES xix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xx SUMMARY xxii PREFACE xxiv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Field of Enquiry 1.2 Approaches to a Social Archaeology 1.2.1 Introduction 1.2.2 Understanding Change 1.2.3 The Nature of the Evidence 1.2.4 Megalithic Cairns and Neolithic Society 1.2.5 Monuments -a Lasting Impression 1.2.6 The Emergence of Individual Power 1.3 Aims, Objectives and Methodology 11 ý1 t ii CHAPTER2 AREA OF STUDY - PHYSICAL FEATURES 20 2.1 Location and Extent 2.2 Definition 2.3 Landforms 2.3.1 Introduction 2.3.2 Highland and Island 2.3.3 Midland Valley 2.3.4 Southern Upland 2.3.5 Climate 2.4 Aspects of the Environment in Prehistory 2.4.1 Introduction 2.4.2 Raised Beach Formation 2.4.3 Vegetation 2.4.4 Climate 2.4.5 Soils CHAPTER 3 FORMATION OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD 38 3.1 Introduction 3.1.1 Definition 3.1.2 Initiation 3.1.3 Social and Economic Change iii 3.2 Period before 1780 3.2.1 The Archaeological Record 3.2.2 Social and Economic Development 3.3 Period 1780 - 1845 3.3.1 The Archaeological Record 3.3.2 Social and Economic Development 3.4 Period 1845 - 1914 3.4.1 Social and Economic -

A5.434 Limaria Hians Beds in Tide-Swept Sublittoral Muddy Mixed Sediment

European Red List of Habitats - Marine Habitat Group A5.434 Limaria hians beds in tide-swept sublittoral muddy mixed sediment Summary The flame or gaping file shell Limaria hians creates nests by weaving together tough threads (byssus) with surrounding material such as seaweed, maerl, shells and detritus. Adjoining nests coalesce to form larger structures often with considerable numbers of flame shells buried within them. In some locations, where conditions allow, contiguous flame shell nests can carpet the bed for several hectares. The carpets create a unique habitat that stabilises the sediment and provides an attachment surface for many organisms including hydroids, bryozoans, ascidians and seaweeds. Flame shell beds are highly vulnerable to seabed trawling and dredging together with other activities which abrade the seabed. There have been few studies on their resilience but they are believed to have a low recoverability when all nest material is removed. Other pressures include smothering, change in hydrological conditions and poor water quality. The control and management of the use of trawls and dredges for demersal fishing is the main measure required for the protection and maintenance of this habitat. In addition, local statutory or voluntary controls on water quality, such as prevention of discharges of contaminated water or the regulation of activities that causes increased turbidity and siltation. Synthesis This habitat has a restricted distribution in the North East Atlantic Region, with current known records confined to the west coast of Scotland and one sea lough in Ireland. There are no long term (>50 year) data sets, but more recent studies show that several known beds in Scotland have declined in extent and density of L. -

To Let 3-5 Cambuslang Way (May Sell) Gateway Office Park, Cambuslang, Glasgow, G32 8Nd Suites from 5,058 Sq Ft – 10,149 Sq Ft (469.9 Sq M – 942.86 Sq M)

TO LET 3-5 CAMBUSLANG WAY (MAY SELL) GATEWAY OFFICE PARK, CAMBUSLANG, GLASGOW, G32 8ND SUITES FROM 5,058 SQ FT – 10,149 SQ FT (469.9 SQ M – 942.86 SQ M) Clowes Developments (Scotland) Ltd cwc-group.co.uk Industrial & Distribution / Office / Retail / Mixed Use / Residential / Leisure Clowes Developments (Scotland) Ltd 9 Coates Crescent, Edinburgh, EH3 7AL t / 0131 225 7265 f / 0131 225 7266 e / [email protected] cwc-group.co.uk Industrial & Distribution / Office / Retail / Mixed Use / Residential / Leisure Modern two storey office pavilion providing flexible open plan office floor space with the benefit of a high quality existing fit out capable of accommodating a wide range of sizes. Specification • Raised access floor • Gas fired central heating Ground Floor • Suspended ceiling with modern lighting • A range of open plan and cellular offices • Boardrooms with comfort cooling • Shower facilities • Staff kitchen facilities installed • Passenger lift • Excellent private car parking – 36 spaces • Cycle racks • EPC C • Equality Act compliant access First Floor Accommodation Floor Size (sq ft) Size (sq m) Ground 5058 469.90 First 5091 472.97 TOTAL 10,149 942.86 Location 3-5 Cambuslang Way is a detached office building within a prominent office park accessed from J2A of the M74 then onto Fullerton Road briefly joining Cambuslang Road and then into Cambuslang Way. Superbly sited for both Scotland’s motorway network and access into Glasgow city centre 4 miles away this location has proved popular with a wide range of local and corporate occupiers. Cambuslang and Carmyle Railway Stations together with various local bus routes are a few minutes away. -

Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District

Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan June 2016 Published by: Glasgow City Council Delivering sustainable flood risk management is important for Scotland’s continued economic success and well-being. It is essential that we avoid and reduce the risk of flooding, and prepare and protect ourselves and our communities. This is first local flood risk management plan for the Clyde and Loch Lomond Local Plan District, describing the actions which will make a real difference to managing the risk of flooding and recovering from any future flood events. The task now for us – local authorities, Scottish Water, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), the Scottish Government and all other responsible authorities and public bodies – is to turn our plan into action. Pagei Foreword Theimpactsoffloodingexperiencedbyindividuals,communitiesandbusinessescanbedevastating andlonglasting.Itisvitalthatwecontinuetoreducetheriskofanysuchfutureeventsandimprove Scotland’sabilitytomanageandrecoverfromanyeventswhichdooccur. ThepublicationofthisPlanisanimportantmilestoneinimplementingtheFloodRiskManagement (Scotland)Act2009andimprovinghowwecopewithandmanagefloodsintheClydeandLoch LomondLocalPlanDistrict.ThePlantranslatesthislegislationintoactionstoreducethedamageand distresscausedbyfloodingoverthefirstplanningcyclefrom2016to2022.ThisPlanshouldberead inconjunctionwiththeFloodRiskManagementStrategythatwaspublishedfortheClydeandLoch LomondareabytheScottishEnvironmentProtectionAgencyinDecember2015. -

Rivers and Streams Play an Important Part in the Recreation 6 Paisley Fulfil Conditions Under the Water Framework Directive and Is Being and Amenity Value of an Area

Current Status - UK and Local A wide variety of riverine habitats occurs in the LBAP Partnership area, ranging from fast flowing upland The River Calder feeds Castle Semple Loch with smaller contributions streams to slow flowing deep sections of river. In this area the main rivers are the White Cart Water, Black coming from the overflows of the Kilbirnie and Barr Lochs. Barr Loch Cart Water, Gryfe and Calder. They are relatively small rivers with the longest being the White Cart Water, was once a meadow with the Dubbs Water draining Kilbirnie Loch into which is 35km in length from its source south of Eaglesham to where it joins the Clyde Estuary at Renfrew. Castle Semple Loch. To preserve some of the marshy habitat in the There are also a number of tributaries that feed these rivers such as the Levern Water, Kittoch Water, Earn area, the Dubbs Water, which drains from Kilbirnie Loch, is channelled Water, Green Water, Dargavel Burn and Locher Water and some smaller watercourses such as the Spango around the outside of the Barr Loch. There is an opportunity to manage Burn. There is also a series of burns flowing down from the Clyde Muirshiel plateau. Land use in the area the area as seasonally flooded wetland (3 Lochs Project). To alleviate varies greatly - there is forest, moorland, agriculture, towns, villages, industrial areas, motorways and parks flooding in the vicinity of Calder Bridge, Lochwinnoch, excavation has amongst others, and each type of land use presents different problems and challenges for biodiversity and recently been carried out. -

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Planning Authority To

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Planning Authority To: Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Planning Authority Joint Committee On: 10th December 2018 Report by Max Hislop, GCV Green Network Partnership Manager GCV Green Network Partnership Business Plan 2017/20 and Programme Plan 2019/20 1. Summary 1.1 The purpose of this report is to update the Joint Committee on the Glasgow and Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership (GCVGNP) Business Plan 2017/20 and to seek approval for local authority contributions to support the Programme Plan and budget for 2019/20. 2. Recommendation 2.1 It is recommended that Joint Committee note the contents of the GCVGNP Business Plan and approve the allocation of local authority contributions to support the delivery of the Programme Plan 2019/20. 3. Background 3.1 The GCVGNP was formed in 2006 and is comprised of the eight Glasgow city region local authorities, Forestry Commission Scotland, SNH, SEPA and the Glasgow Centre Population Health. 3.2 The purpose of the GCVGNP is to facilitate the delivery of the GCV Green Network, a key component of the Strategic Development Plan’s Spatial Development Strategy. The GCVGNP is also a key regional partner in the Central Scotland Green Network, a ‘National Development’ in NPF3. 3.3 The GCVGNP has been successful in generating increased recognition of the role of the Green Network in delivering a successful city region. Current work is providing strategic guidance for the delivery of the Green Network and green infrastructure to deliver healthier lifestyles, climate change resilience, training and employment opportunities and placemaking developments.