Arbitration Newsletter Switzerland Gert Thys' Longest Marathon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

START LIST Marathon MEN OSANOTTAJALUETTELO Maraton

10th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki From Saturday 6 August to Sunday 14 August 2005 Marathon MEN Maraton MIEHET ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHL START LIST OSANOTTAJALUETTELO ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETI 1 3 13 August 2005 14:20 BIB COMPETITOR NAT YEAR Personal Best 2005 Best 568 Jimmy MUINDI KEN 73 2:07:50 2:07:50 554 Robert CHEBOROR KEN 78 2:06:23 569 Wilson ONSARE KEN 76 2:06:47 2:12:21 570 Joseph RIRI KEN 73 2:06:49 2:09:00 552 Paul BIWOTT KEN 78 2:08:17 2:08:17 518 Michitaka HOSOKAWA JPN 76 2:09:10 2:09:10 541 Wataru OKUTANI JPN 75 2:09:13 2:09:13 544 Toshinari TAKAOKA JPN 70 2:06:16 2:07:41 519 Satoshi IRIFUNE JPN 75 2:09:58 2:09:58 539 Tsuyoshi OGATA JPN 73 2:08:37 806 Dmitriy BURMAKIN RUS 81 2:11:20 2:11:20 802 Oleg BOLKHOVETS RUS 76 2:11:17 2:13:33 800 Georgiy ANDREYEV RUS 76 2:11:20 2:11:20 98 Clodoaldo DA SILVA BRA 78 2:13:12 2:13:12 99 Vanderlei DE LIMA BRA 69 2:08:31 110 Claudir RODRIGUES BRA 76 2:15:27 102 Marilson Gomes DOS SANTOS BRA 77 2:08:48 109 André Luiz RAMOS BRA 70 2:08:26 2:15:37 290 Francis KIRWA FIN 74 2:16:08 2:16:08 286 Janne HOLMÉN FIN 77 2:12:10 295 Tuomo LEHTINEN FIN 79 2:16:45 2:16:45 302 Yrjö PESONEN FIN 64 2:17:05 2:22:13 452 Wodage -

Course Records Course Records

Course records Course records ....................................................................................................................................................................................202 Course record split times .............................................................................................................................................................203 Course record progressions ........................................................................................................................................................204 Margins of victory .............................................................................................................................................................................206 Fastest finishers by place .............................................................................................................................................................208 Closest finishes ..................................................................................................................................................................................209 Fastest cumulative races ..............................................................................................................................................................210 World, national and American records set in Chicago ................................................................................................211 Top 10 American performances in Chicago .....................................................................................................................213 -

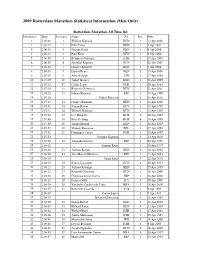

2009 Rotterdam Marathon Statistical Information (Men Only)

2009 Rotterdam Marathon Statistical Information (Men Only) Rotterdam Marathon All Time list Performances Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:05:49 1 William Kipsang KEN 1 13 Apr 2008 2 2:06:14 2 Felix Limo KEN 1 4 Apr 2004 3 2:06:38 3 Sammy Korir KEN 1 9 Apr 2006 4 2:06:44 4 Paul Kirui KEN 2 9 Apr 2006 5 2:06:50 5 Belayneh Dinsamo ETH 1 17 Apr 1988 6 2:06:50 6 Josephat Kiprono KEN 1 22 Apr 2001 7 2:06:52 7 Charles Kibiwott KEN 3 9 Apr 2006 8 2:06:58 8 Daniel Rono KEN 2 13 Apr 2008 9 2:07:07 9 Ahmed Salah DJI 2 17 Apr 1988 10 2:07:09 10 Japhet Kosgei KEN 1 18 Apr 1999 11 2:07:12 11 Carlos Lopes POR 1 20 Apr 1985 12 2:07:18 12 Kenneth Cheruiyot KEN 2 22 Apr 2001 13 2:07:23 13 Fabian Roncero ESP 2 18 Apr 1999 14 2:07:26 Fabian Roncero 1 19 Apr 1998 15 2:07:33 14 Charles Kamathi KEN 3 13 Apr 2008 16 2:07:41 15 Simon Biwott KEN 3 18 Apr 1999 17 2:07:42 16 William Kiplagat KEN 1 13 Apr 2003 18 2:07:44 17 Lee Bong-Ju KOR 2 19 Apr 1998 19 2:07:49 18 Kim Yi-Yong KOR 4 18 Apr 1999 20 2:07:50 19 Jimmy Muindi KEN 1 10 Apr 2005 21 2:07:51 20 Vincent Rousseau BEL 1 17 Apr 1994 22 2:07:51 21 Domingos Castro POR 1 20 Apr 1997 23 2:07:53 Josephat Kiprono 2 13 Apr 2003 24 2:07:54 22 Alejandro Gomez ESP 2 20 Apr 1997 25 2:08:02 Sammy Korir 3 20 Apr 1997 26 2:08:02 23 Jackson Koech KEN 2 10 Apr 2005 27 2:08:09 24 Jose Manuel Martinez ESP 3 13 Apr 2003 28 2:08:14 Samy Korir 3 22 Apr 2001 29 2:08:19 25 Simon Loywapet KEN 4 20 Apr 1997 30 2:08:21 26 Joshua Chelanga KEN 1 15 Apr 2007 31 2:08:22 27 Kenneth Cheruiyot KEN 1 16 Apr 2000 32 2:08:30 28 Francisco -

Chicago Year-By-Year

YEAR-BY-YEAR CHICAGO MEDCHIIAC INFOAGO & YEFASTAR-BY-Y FACTSEAR TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR-BY-YEAR HISTORY 2011 Champion and Runner-Up Split Times .................................... 126 2011 Top 25 Overall Finishers ....................................................... 127 2011 Top 10 Masters Finishers ..................................................... 128 2011 Top 5 Wheelchair Finishers ................................................... 129 Chicago Champions (1977-2011) ................................................... 130 Chicago Champions by Country ...................................................... 132 Masters Champions (1977-2011) .................................................. 134 Wheelchair Champions (1984-2011) .............................................. 136 Top 10 Overall Finishers (1977-2011) ............................................. 138 Historic Event Statistics ................................................................. 161 Historic Weather Conditions ........................................................... 162 Year-by-Year Race Summary............................................................ 164 125 2011 CHAMPION/RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS 2011 CHAMPION AND RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS MEN MEN Moses Mosop (KEN) Wesley Korir (KEN) # Name Age Country Time Distance Time (5K split) Min/Mile/5K Time Sec. Back 1. Moses Mosop ..................26 .........KEN .................................... 2:05:37 5K .................00:14:54 .....................04:47 -

10Th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki (FIN) - Saturday, Aug 06, 2005 Shot Put - M QUALIFICATION Qual

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki (FIN) - Saturday, Aug 06, 2005 Shot Put - M QUALIFICATION Qual. rule: qualification standard 20.25m or at least best 12 qualified. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Group A 06 August 2005 - 10:00 Position Bib Athlete Country Mark . 1 971 Christian Cantwell USA 21.11 Q . 2 200 Joachim Olsen DEN 20.85 Q . 3 75 Andrei Mikhnevich BLR 20.54 Q . 4 1012Adam Nelson USA 20.35 Q . 5 304 Tepa Reinikainen FIN 20.19 q . 6 727 Tomasz Majewski POL 20.12 q . 7 363 Carl Myerscough GBR 20.07 q . 8 774 Gheorghe Guset ROU 19.83 . 9 239 Manuel Martínez ESP 19.55 . 10 194 Petr Stehlík CZE 19.48 . 11 853 Miran Vodovnik SLO 19.28 . 12 838 Ivan Yushkov RUS 18.98 . 13 143 Marco Antonio Verni CHI 18.60 . 14 509 Dorian Scott JAM 18.33 . 840 Shaka Sola SAM DNS . Athlete 1st 2nd 3rd Christian Cantwell 21.11 Joachim Olsen 20.16 19.82 20.85 Andrei Mikhnevich 20.54 Adam Nelson X 20.35 Tepa Reinikainen 19.87 20.19 20.06 Tomasz Majewski 20.04 20.12 20.09 Carl Myerscough 19.88 20.07 19.68 Gheorghe Guset 19.44 19.60 19.83 Manuel Martínez 19.49 19.55 19.28 Petr Stehlík 18.98 19.48 X Miran Vodovnik 18.60 18.58 19.28 Ivan Yushkov 18.77 18.98 X Marco Antonio Verni X X 18.60 Dorian Scott 18.10 X 18.33 Shaka Sola Group B 06 August 2005 - 10:00 Position Bib Athlete Country Mark . -

2010 Fukuoka Marathon Statistics by K. Ken Nakamura

2020201020 101010 Fukuoka Marathon Statistical Information Fukuoka Marathon All Time list Performances Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:05:18 1 Tsegaye Kebede ETH 1 6 Dec 2009 2 2:06:10 Tsegaye Kebede 1 7 Dec 2008 3 2:06:39 2 Samuel Wanjiru KEN 1 2 Dec 2007 4 2:06:50 3 Deriba Merga ETH 2 2 Dec 2007 5 2:06:51 4 Atsushi Fujita JPN 1 3 Dec 2000 6 2:06:52 5 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 1 3 Dec 2006 7 2:07:13 6 Atsushi Sato JPN 3 2 Dec 2007 8 2:07:15 7 Dmytro Barnovskyy UKR 2 3 Dec 2006 9 2:07:19 8 Jaouad Gharib MAR 3 3 Dec 2006 10 2:07:28 9 Josiah Thugwane RSA 1 7 Dec 1997 11 2:07:52 10 Tomoaki Kunichika JPN 1 7 Dec 2003 12 2:07:52 11 Kebede Tekeste ETH 2 6 Dec 2009 13 2:07:54 12 Gezahegne Abera ETH 1 5 Dec 1999 14 2:07:55 13 Mohammed Ouaadi FRA 2 5 Dec 1999 15 2:07:55 14 Toshinari Suwa JPN 2 7 Dec 2003 16 2:07:59 15 Toshinari Takaoka JPN 3 7 Dec 2003 17 2:08:07 16 Toshiyuki Hayata JPN 2 7 Dec 1997 18 2:08:10 17 Antonio Peña ESP 4 7 Dec 2003 19 2:08:18 18 Robert de Castella AUS 1 6 Dec 1981 20 2:08:18 19 Takeyuki Nakayama JPN 1 6 Dec 1987 21 2:08:19 Dmytro Barnovskyy 3 6 Dec 2009 22 2:08:21 20 Hailu Negussie ETH 5 7 Dec 2003 23 2:08:29 Dmytro Barnovskyy 1 4 Dec 2005 24 2:08:36 21 Dereje Tesfaye Gebrehiwot ETH 4 6 Dec 2009 25 2:08:37 22 Tsuyoshi Ogata JPN 6 7 Dec 2003 26 2:08:40 23 Vanderlei de Lima BRA 3 5 Dec 1999 27 2:08:42 24 Jackson Kabiga KEN 1 6 Dec 1998 28 2:08:47 25 Nozomi Saho JPN 3 7 Dec 1997 29 2:08:48 26 Nobuyuki Sato JPN 2 6 Dec 1998 30 2:08:48 27 Tadayuki Ojima JPN 7 7 Dec 2003 31 2:08:49 28 Wataru Okutani JPN 4 3 Dec 2006 32 -

— Kebede Prs to Win Fukuoka Marathon — from K

Volume 7, No. 60 December 8, 2008 — Kebede PRs To Win Fukuoka Marathon — From K. Ken Nakamura PR by a half-minute from the 2:06:40 he ran FUKUOKA MARATHON Fukuoka, Japan, December 7—Breaking in April to win the Paris race. 1. Kebede (Eth) 2:06:10 PR (12, x W) away from his pursuers after 30K and then “I’m very happy,” said the Beijing bronze (course record—old cr 2:06:39 Wanjiru [Ken] covering the next 5000 in an astonishing medalist, who moved to No. 12 performer ’07) (1:04:02/1:02:08); all-time. “The result 2. Irifune (Jpn) 2:09:23; 3. Fujiwara (Jpn) is better than I ex- 2:09:47; 4. Sato (Jpn) 2:09:59; 5. F. Limo pected.” (Ken) 2:10:59; The pack passed 6. J. Martinez (Spa) 2:11:11; 7. Makori the halfway point in (Ken) 2:11:54; 8. Matsumiya (Jpn) 2:12:18; 1:04:02 and by 25K 9. Brown (Can) 2:12:27; 10. Aburaya (Jpn) (1:15:49) the lead 2:13:48. group numbered 14. The real racing started shortly after — Foot Locker HS Cross as Kebede pushed the pace and strung Regionals — out the pack. MIDWEST At 30K, Kebede Kenosha, Wisconsin, November 29— racheted up the 5K: 1. Zivec (GrandRapids, Mn) 15:09; 2. tempo again and Manilafasha (Denver, Co) 15:13. dropped the remain- Girls: 1. Goethals (Rochester, Mi) 17:31; ing pursuers. 2. Sisson (Chesterfield, Mo) 17:32. He then nailed the coffin shut NORTHEAST with his incredible Bronx, New York, November 29—1. -

South African Yearbook 2004/05: Sport and Recereation

20 Sport.qxp 1/24/05 9:30 AM Page 519 20 Sport and recreation Since 1994, sport has been making a substantial The SRSA is directly responsible for: contribution to nation-building and reconciliation in • Managing the vote for sport and recreation in the South Africa. national Government. Sport and Recreation South Africa (SRSA) and the • Supporting the Minister of Sport and Recreation. South African Sports Commission (SASC) are • Co-ordinating and contributing to the drafting of responsible for policy, provision and facilitation of legislation on sport and recreation. sport and recreation delivery in the country. • Interpreting broad government policy, translating The key objectives of the SRSA are to: government policy into policies for sport and recre- • increase the level of participation in sport and ation, revising such policy if and when necessary, recreational activities and monitoring the implementation thereof. • raise the profile of sport • Aligning sport and recreation policy with the poli- • maximise the probability of success in major cies of other government departments in the sporting events spirit of integrated planning and delivery. • place sport at the forefront of efforts to reduce • Providing legal advice to all stakeholders in sport crime. and recreation from a government perspective. 519 20 Sport.qxp 1/24/05 9:30 AM Page 520 • Subsidising clients of the SRSA in accordance • Communicating sport and recreation-related with the Public Finance Management Act, 1999 matters from a government perspective. (Act 1 of 1999), its concomitant regulations, as • Co-ordinating and monitoring the creation and well as the SRSA funding policy; monitoring the upgrading of sport and recreation infrastructure application of such funds; and advising clients on through the Building for Sport and Recreation the management of their finances. -

Number of Sub-2:0X Marathons

Number of Sub-2:0X marathons Runners with Sub-2:04 Name Number 1 2 3 Haile Gebrselassie 1 2:03:59 Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich 1 2:03:42 Geoffrey Mutai 1 2:03:02 Moses Mosop 1 2:03:06 Patrick Makau 1 2:03:38 Runners with multiple Sub-2:05 Name Number 1 2 3 Haile Gebrselassie 3 2:03:59 2:04:26 2:04:53 Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich 3 2:03:42 2:04:44 2:04:57 Geoffrey Mutai 3 2:03:02 2:04:15 2:04:55 Patrick Makau 2 2:03:38 2:04:48 Runners with multiple Sub-2:06 Name Number 1 2 3 4 5 Haile Gebrselassie 5 2:03:59 2:04:26 2:04:53 2:05:29 2:05:56 Geoffrey Mutai 5 2:03:02 2:04:15 2:04:55 2:05:06 2:05:10 Patrick Makau 4 2:03:38 2:04:48 2:05:08 2:05:45 Tsegaye Kebede 4 2:04:38 2:05:18 2:05:19 2:05:20 Samuel Wanjiru 3 2:05:10 2:05:24 2:05:41 Khalid Khannouchi 3 2:05:38 2:05:42 2:05:56 Vincent Kipruto 3 2:05:13 2:05:33 2:05:47 Moses Mosop 3 2:03:06 2:05:03 2:05:37 Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich 3 2:03:42 2:04:44 2:04:57 Wilson Chebet 3 2:05:27 2:05:41 2:05:53 James Kwambai 3 2:04:27 2:05:36 2:05:50 Paul Tergat 2 2:04:55 2:05:48 Martin Lel 2 2:05:15 2:05:45 Abdullah Dawit Shami 2 2:05:42 2:05:58 Tadesse Tola 2 2:04:49 2:05:10 Tilahun Regassa 2 2:05:27 2:05:38 Getu Feleke 2 2:04:50 2:05:44 Runners with multiple Sub-2:07 Name No. -

South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their Ni Ternational Careers During and After Apartheid Carrie A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1999 South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their nI ternational Careers During and After Apartheid Carrie A. Lane Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Physical Education at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Lane, Carrie A., "South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their nI ternational Careers During and After Apartheid" (1999). Masters Theses. 1530. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1530 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university or the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.form South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their International Careers During and After Apartheid (TITLE) BY Carrie A. -

2013 Fukuoka Marathon Marathon Marathon Statistical

2020201320 131313 Fukuoka Marathon Statistical Information Fukuoka Marathon All Time list Performances Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:05:18 1 Tsegaye Kebede ETH 1 6 Dec 2009 2 2:06:10 Tsegaye Kebede 1 7 Dec 2008 3 2:06:39 2 Samuel Wanjiru KEN 1 2 Dec 2 007 4 2:06:50 3 Deriba Merga ETH 2 2 Dec 2007 5 2:06:51 4 Atsushi Fujita JPN 1 3 Dec 2000 6 2:06:52 5 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 1 3 Dec 2006 7 2:06:58 6 Joseph Gitau KEN 1 2 Dec 2012 8 2:07:13 7 Atsushi Sato JPN 3 2 Dec 2007 9 2:07:15 8 Dmytro Barnovsk yy UKR 2 3 Dec 2006 10 2:07:19 9 Jaouad Gharib MAR 3 3 Dec 2006 11 2:07:28 10 Josiah Thugwane RSA 1 7 Dec 1997 12 2:07:36 11 Josphat Ndambiri KEN 1 4 Dec 2011 13 2:07:52 12 Tomoaki Kunichika JPN 1 7 Dec 2003 14 2:07:52 13 Kebede Tekeste ETH 2 6 Dec 200 9 15 2:07:54 14 Gezahegne Abera ETH 1 5 Dec 1999 16 2:07:55 15 Mohammed Ouaadi FRA 2 5 Dec 1999 17 2:07:55 16 Toshinari Suwa JPN 2 7 Dec 2003 18 2:07:59 17 Toshinari Takaoka JPN 3 7 Dec 2003 19 2:08:07 18 Toshiyuki Hayata JPN 2 7 Dec 1997 20 2:08:10 19 Antonio Peña ESP 4 7 Dec 2003 21 2:08:18 20 Robert de Castella AUS 1 6 Dec 1981 22 2:08:18 21 Takeyuki Nakayama JPN 1 6 Dec 1987 23 2:08:19 Dmytro Barnovskyy 3 6 Dec 2009 24 2:08:21 22 Hailu Negussie ETH 5 7 Dec 2003 25 2:08:24 Jaouad Gharib 1 5 Dec 2010 26 2:08:24 23 Hiroyuki Horibata JPN 2 2 Dec 2012 27 2:08:29 Dmytro Barnovsk yy 1 4 Dec 2005 28 2:08:36 24 Dereje Tesfaye Gebrehiwot ETH 4 6 Dec 2009 29 2:08:37 25 Tsuyoshi Ogata JPN 6 7 Dec 2003 30 2:08:38 26 James Mwangi KEN 2 4 Dec 2011 31 2:08:40 27 Vanderlei de Lima BRA 3 5 Dec 1999 -

Distance Running Results Vol

Distance Running Results Vol. 13, No. 22 – 3 June 2013 © Distance Running Results. All rights reserved. ____________________________________________________________________ Distance Running Results (DRR) publishes results of races 800 metres and longer from all over the world with the focus on South African results. DRR is available by subscription only. For subscription information send an e-mail to the address at the end of this issue. Publisher: Riël Hauman ____________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL If there is such a thing as an undramatic Comrades Marathon, this one was it. Claude Moshiywa was at the front of the 88 th Comrades since he took the lead on one of the five big hills, Inchanga, soon after the halfway mark and for the last 90 minutes he ran unchallenged to the finish in Pietermaritzburg. The hot and very windy conditions slowed him over the last 10 km and he had an especially tough time up the last hill, Polly Shorts, which crests just less than 8 km from the end, but he won comfortably in 5:32:08 to become the first South African winner of the “up” run since Jetman Msutu took the title in 1992. Moshiywa’s winning margin over the Swede Jonas Buud, who sliced through the field in the second half, was 9:12. The reigning “down” run champion, Ludwick Mamabolo, finished fourth, while defending up run champion Stephen Muzinghi took the last gold medal. Five South African men finished in the top ten. In the women’s race it was business as usual, with the Nurgalieva twins filling the first two positions. Elena got her eighth victory, just one short of the record nine of Bruce Fordyce, in 6:27:08.