Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Health in Hamilton's North End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton's Heritage Volume 5

HAMILTON’S HERITAGE 5 0 0 2 e n u Volume 5 J Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act Hamilton Planning and Development Department Development and Real Estate Division Community Planning and Design Section Whitehern (McQuesten House) HAMILTON’S HERITAGE Hamilton 5 0 0 2 e n u Volume 5 J Old Town Hall Reasons for Designation under Part IV Ancaster of the Ontario Heritage Act Joseph Clark House Glanbrook Webster’s Falls Bridge Flamborough Spera House Stoney Creek The Armoury Dundas Contents Introduction 1 Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the 7 Ontario Heritage Act Former Town of Ancaster 8 Former Town of Dundas 21 Former Town of Flamborough 54 Former Township of Glanbrook 75 Former City of Hamilton (1975 – 2000) 76 Former City of Stoney Creek 155 The City of Hamilton (2001 – present) 172 Contact: Joseph Muller Cultural Heritage Planner Community Planning and Design Section 905-546-2424 ext. 1214 [email protected] Prepared By: David Cuming Natalie Korobaylo Fadi Masoud Joseph Muller June 2004 Hamilton’s Heritage Volume 5: Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act Page 1 INTRODUCTION This Volume is a companion document to Volume 1: List of Designated Properties and Heritage Conservation Easements under the Ontario Heritage Act, first issued in August 2002 by the City of Hamilton. Volume 1 comprised a simple listing of heritage properties that had been designated by municipal by-law under Parts IV or V of the Ontario Heritage Act since 1975. Volume 1 noted that Part IV designating by-laws are accompanied by “Reasons for Designation” that are registered on title. -

City of Hamilton

Authority: Item 1, Board of Health Report 18-005 (BOH07034(l)) CM: May 23, 2018 Ward: City Wide Bill No. 148 CITY OF HAMILTON BY-LAW NO. 18- To Amend By-law No. 11-080, a By-law to Prohibit Smoking within City Parks and Recreation Properties WHEREAS Council enacted a By-law to prohibit smoking within City Parks and Recreation Properties, being City of Hamilton By-law No. 11-080; AND WHEREAS this By-law amends City of Hamilton By-law No.11-080; NOW THEREFORE the Council of the City of Hamilton enacts as follows: 1. Schedule “A” of By-law No. 11-080 is deleted and replaced by the Schedule “A” attached to and forming part of this By-law, being an updated list of the location of properties, addresses, places and areas where smoking is prohibited. 2. This By-law comes into force on the day it is passed. PASSED this 13th day of June, 2018. _________________________ ________________________ F. Eisenberger J. Pilon Mayor Acting City Clerk Schedule "A" to By-law 11-080 Parks and Recreation Properties Where Smoking is Prohibited NAME LOCATION WARD 87 Acres Park 1165 Green Mountain Rd. Ward 11 A.M. Cunningham Parkette 300 Roxborough Dr. Ward 4 Agro Park 512 Dundas St. W., Waterdown Ward 15 Albion Estates Park 52 Amberwood St. Ward 9 Albion Falls Nghd. Open Space 221 Mud Street Ward 6 Albion Falls Open Space (1 & 2) 199 Arbour Rd. Ward 6 Albion Falls Park 768 Mountain Brow Blvd. Ward 6 Alexander Park 201 Whitney Ave. Ward 1 Allison Neighbourhood Park 51 Piano Dr. -

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Comprehensive Study Report Prepared for: Environment Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Transport Canada Hamilton Port Authority Prepared by: The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group AECOM October 30, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group Members: Roger Santiago, Environment Canada Erin Hartman, Environment Canada Rupert Joyner, Environment Canada Sue-Jin An, Environment Canada Matt Graham, Environment Canada Cheriene Vieira, Ontario Ministry of Environment Ron Hewitt, Public Works and Government Services Canada Bill Fitzgerald, Hamilton Port Authority The Technical Task Group gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following parties in the preparation and completion of this document: Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Hamilton Port Authority, Health Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ontario Ministry of Environment, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act Agency, D.C. Damman and Associates, City of Hamilton, U.S. Steel Canada, National Water Research Institute, AECOM, ARCADIS, Acres & Associated Environmental Limited, Headwater Environmental Services Corporation, Project Advisory Group, Project Implementation Team, Bay Area Restoration Council, Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan Office, Hamilton Conservation Authority, Royal Botanical Gardens and Halton Region Conservation Authority. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. -

September 2019

membership renewal inside! JOURNAL OF THE HAMILTON NATURALISTS’ CLUB Protecting Nature Since 1919 Volume 73 Number 1 Celebrating 100 Years! September 2019 available in October 2019 Table of Contents A Fond Farewell Ronald Bayne 4 HNC Centenary Commemorative Pin of a Wood Duck Beth Jefferson 5 HNC Hike Report - Butterflies and Dragonflies Paul Philp 6 Noteworthy Bird Records — December to February, 2018-19 Bill Lamond 7 Dates to Remember – September & October 2019 Rob Porter/Liz Rabishaw 12 Reflections From the Past - Wood Duck Articles from the mid-1950s Various authors 14 2018 Robert Curry Award and Wildfowl at Slimbridge Wetland Michael Rowlands 17 Great Egret June Hitchcox 18 Field Thistle in the Hamilton Study Area Bill Lamond 19 The Roots that Grow Deep: Trees, Heritage and Conservation Bronwen Tregunno 21 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of the HNC – 15 Oct 2018 Joyce Litster 22 Building Hamilton’s Pollinator Paradise Jen Baker 23 100th Anniversary Dinner Tickets Now Available !!! “A special anniversary should have a special celebration and when it’s your 100th anniversary, that celebration should be extra-special! We are capping our 100th anniversary year with a prestigious dinner event at the beautiful Liuna Station in downtown Hamilton on Saturday, 2 November. Michael Runtz, a natural history lecturer, writer, photographer, and broadcaster, will be our guest speaker. See Debbie Lindeman after Club meetings to purchase your ticket for $75.00. You don’t have the money right now? Don’t worry, she’ll be selling tickets at the Monthly and Bird Study Group meetings in September and October leading up to the big event. -

CITY COUNCIL MINUTES 18-001 5:00 P.M

4.1 CITY COUNCIL MINUTES 18-001 5:00 p.m. Wednesday, January 24, 2018 Council Chamber Hamilton City Hall 71 Main Street West Present: Mayor F. Eisenberger, Deputy Mayor Aidan Johnson Councillors J. Farr, M. Green, S. Merulla, C. Collins, T. Jackson, D. Skelly, T. Whitehead, D. Conley, M. Pearson, B. Johnson, L. Ferguson, A. VanderBeek, R. Pasuta and J. Partridge. Mayor Eisenberger called the meeting to order and recognized that Council is meeting on the traditional territories of the Mississauga and Haudenosaunee nations, and within the lands protected by the ―Dish with One Spoon‖ Wampum Agreement. The Mayor called upon Paul Neissen, a member of the Board of the Christian Salvage Mission and the Family Council for Regina Gardens to provide the invocation. CEREMONIAL ACTIVITY 3.1 40th Anniversary of the Hamilton Winterfest The Mayor recognized the following citizens and neighbourhood associations for their contributions to Winterfest festivities throughout the City: Rosalind Brenneman, Jim Auty - Friends of Gage Park and Gage Park Winterfest Gerry Polmanter, Mike Siden - North Central Community Association and North Central Winterfest Karen Marcoux, Randy Chapple – Gourley Park Community Association, Gourley Park Winterfest Council Minutes 18-001 January 24, 2018 Page 2 of 26 APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA The Clerk advised of the following changes to the agenda: 1. ADDED NOTICES OF MOTION (Item 8) 8.1 2015 and 2016 Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority Levy Apportionment (LS16020(a)) 8.2 Attracting Diversity in the Selection Process 8.3 Community Grants for Ward 3 8.4 Dedicating the ArcelorMittal Dofasco Fine to Greening Initiatives in East Hamilton (Ward 4) 2. -

Downtown Hamilton Development Opportunity

71 REBECCA STREET APPROVED DOWNTOWN HAMILTON DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 1 CONTACT INFORMATION BRETT TAGGART* Sales Representative 416 495 6269 [email protected] BRAD WALFORD* Vice President 416 495 6241 [email protected] SEAN COMISKEY* Vice President 416 495 6215 [email protected] CASEY GALLAGHER* Executive Vice President 416 815 2398 [email protected] TRISTAN CHART* Senior Financial Analyst 416 815 2343 [email protected] 2 *Sales Representative TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2. PROPERTY PROFILE 3. DEVELOPMENT OVERVIEW 4. LOCATION OVERVIEW 5. MARKET OVERVIEW 6. OFFERING PROCESS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 01 5 THE OFFERING // EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CBRE Limited (“CBRE “or “Advisor”) is pleased to offer for sale 71 Rebecca Street (the “Property” or “Site”), an approved mixed-use development opportunity with a total Gross Floor Area (GFA) of 327,632 sq. ft. The development opportunity includes a maximum building height of 318 ft. (30 storeys) containing 313 dwelling units, with 13,240 sq. ft. of commercial floor area on the ground floor on 0.78 ac. of land along the north side of Rebecca Street, between John Street North to the west and Catharine Street North to the east in the heart of Downtown Hamilton. Positioned within close proximity to both the Hamilton GO Centre Transit Station and the West Harbour GO Transit Station, this offering presents a rare opportunity to acquire a major development land parcel that is ideally positioned to address the significant demand for both new housing and mixed-use space in Hamilton. 71 Rebecca Street is currently improved with a single storey building that was originally built as a bus terminal and operated by Grey Coach and Canada Coach Bus Lines until 1996. -

Life Lease Housing Advantage

“There’s a vintage that comes with age and experience.” BON JOVI THE VOICE OF ST. ELIZABETH MILLS Vol. 5 2018 Live Every Day Like You’re On Resort-style Living at Upper Mill Pond Vacation See more on page TWO LOCAL LOVE LIFE LEASE IN THE VILLAGE WHO’S WHO ZESTful EVENTS Ten Reasons to Life Lease 8 Great Reasons Meet The Special Canada Day Live in Hamilton Housing to Buy at Sabatino’s Celebration What a great place to live! Advantage Upper Mill Pond They fell in love with Special Canada Day Celebration at Upper Mill Pond The Village at St. Elizabeth Mills Where the smart money is. Buy now at pre-construction prices! Don’t’ Miss Out! FOUR SIX SEVEN SEVEN EIGHT VOL. 5 2018 The Village News The Voice of St. Elizabeth Mills LIVINGWITHZEST.COM Fitness Club Part of the state-of-the-art Health Club, the Fitness Centre is outfitted with the latest cardio and gym equipment within a bright and beautiful setting that will make you look forward to working out. LIVE EVERY DAY LIKE IT’S A VACATION It isn’t just the incredible Health Club. It isn’t just the Juice Bar in the lobby or the stunning recreational space. Pool & Spa It’s the attitude of fun and action that makes Upper Mill Pond The stunning swimming pool at the perfect place to live. Upper Mill Pond offers 5-star luxury with bright windows that overlook the beautiful grounds and lots of places to relax with friends. Suites at Upper Mill Pond are on sale now. -

Noteworthy Bird Records Fall (September to November) 2020

Hamilton Study Area Noteworthy Bird Records Fall (September to November) 2020 Scarlet Tanager at Malvern Rd, Burlington 16 September 2020 - photo Phil Waggett. Hello, This is the new format of the Noteworthy Bird Records for the Hamilton Naturalists's Club. After more than 70 years of bird records being published almost monthly in the Wood Duck, the journal of the HNC, this is the first time they have been published in a separate publication. Seventy years is a very long time and it is with heavy heart that I break with this tradition. It is not done without a lot of reflection. I would have preferred that the NBR continue in theWood Duck as before, but these records were taking up more and more space in that publication and perhaps limiting the inclusion of other articles. To try to reduce the size of the NBR, I had taken to making the type face smaller and smaller which was making it increasingly difficult to read (difficult enough already with the reams and reams of records). I had asked for comments from Club members about whether or not they wanted to see the NBR continue within the Wood Duck or in a separate format. I did not get many replies. However, of those few replies, all of them suggested removing the NBR from the Wood Duck. This is what I have done. I have made this decision while I am still a co-editor of the Wood Duck. Soon I will no longer be the editor and I cannot expect future editors to publish these voluminous reports. -

Gartshore-Thomson Building, Pier 4 Park, Hamilton, Ontario, Adopted by City Council at Its Meeting Held 1994 • May 31

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. -------------~~....... -~ --..-~~~~~~~~~ -,: -· - . - . ..__, ,, - ... ,.,-,.. ' . •',,•,'·'' ···,~- ,,·'1.',-· '''' -,. ,..,, . ' .. )1',..'l ,,,. ,.. ... •· \'. ;, . •·,'· ,,i,_·.,.· ~ •'I• , . '•/bi'' -t ••. .'_.,,.•,-.' . .. ' . ' ' ' - • '. ',, . ,. ,. ' .. OFFICE OF THE CITY CLERK , ' , r • • • - . ' ' . ' . • • • .. - ' . ' . • • • • • • • . • . , . ' .' . .. 71 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, LSN 3T4 Tel. (905) 546-2 Q:Q. l,,Fa1C (905) 546-2095 "'~ ~ .. - •• ,;·~ -~ l~i!b£'1'.'f-;l1\ • , .' .. \f~,5,'f,l!;.~\l}~j ~ : {tll v~~~ &,i,:~ REGISTERED Jlm 30 f994 • 1994 June 24 • l • ¥Y'•' ,-................._...,._.._ r -·· .. --·····~ ' The Ontario Heritage Foundation • 10 Adeiaide Street East Toronto, ON MSC 1J3 28 JUN ..... ~ ...... ,._,. ___ _ Dear Sir: --------- Re: Notification of Passing of By-law Attached for your information is a copy of By-law No. 94-094 respecting Gartshore-Thomson Building, Pier 4 Park, Hamilton, Ontario, adopted by City Council at its meeting held 1994 • May 31. Yours truly, ' J. J. Schatz ' r·""Jty Cl_er k~ JJS/bc att. c.c. V. J. Abraham, Director of Local Planning Attention: Nina Chapple, Architectural Historian • A. Zuidema, Law Department C. Touzel, Secretary, L.A.C.A.C. • ,_. • Bill No. C-27 ' The Corporation of the City of Hamilton BY-LAW NO. 94- 091, JUN 30 1994 To Designate: 28 JUN 1~94 As Property of: _.. ____ _ -------------" HISTORIC AND ARCHITECTURAL VALUE AND INTEREST REAS the Council of The Corporation of the City of Hamilton did give notice of its intention to designate the property mentioned in section 1 of this by-law in accordance with subsection 29(3) of the Ontario Heritage Act, R.S.O. -

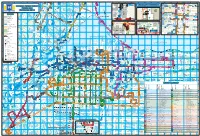

HSR Customer C D O W Hunter St

r r C D e k a r n o r s D o t b is t t r r a l Mo L s C n e D m e te s e e n g v n S r R o h i P M C o a C s m h o o r K W O i e C lo s ms a M a m n F d g s lk d u ff o A s i a H te on r e n C i r u a Dr t y N te a lic l r e a g y o v L rm ic C de 's u n r t R e P a a e D F A ld l s ti a Cumberlandd t o l n L v r t u a n iti n W i l r C in r gh a y n a u e o D D e o a D C Dr e w m S d r r a s m t A M n e r o C v a C C M e v A S F lv R h e l R c t t lm l v Guelph Line e or v e W G A r c r re a P a v v Laurentian en L n R en A R i c a l d s a yatt Rd b a r t D v A c e ni A t a s C r d e a T n t ie ie A t u C C o r k t h rt n D i r t r d g C a e la Dr C il r a r e a p e R e C M y A kvi D C T y a e n v O a d R w r C l a L o k B t w w F O A e e k T o L v l e o a La r a d a u r v n k f le R a is w D e or a d d to ic r sid t t Pear id P Fi c k Spruce e C C M s k M ge h P v S A t C ree gsbrid o D l Brant St M Kin s er H r ap New St Pi O im v T s o A n h G A m le e ak o t r r Ct Fisherv n r l e h a l C w r e D C n w il l s e C o l L i o o D o w o D r ve o r N o h d t n l p t M d Harvester Rd D r e a R ic r w C to r D y e y L d h w l o n t olson Ct o r o e M a p A l c f s e B s v il m z B a s R u u d r d ln B P a d U G a u r r o a er le W W e a v C n r t p c rtv T H l R D C ko e r S iew B mesbu d P r nd r y R B H ay Dr A r d r F a ingw D Concession 8 E C m y i a D o r l e u e t m C n R h s i t r e J tl C e S w e d o a t r C l l W n d c t l A a h C e a s s r l n t i d n e a l rpi D R J r e n e li s to r A r vl e e le n v n C t n v i t d g o C ffe -

Arts in the City: Visions of James Street North, 2005-2011

PhD Thesis – V. E. Sage McMaster University – Dept. of Anthropology VISIONS OF JAMES STREET NORTH PhD Thesis – V. E. Sage McMaster University – Dept. of Anthropology Title Page ARTS IN THE CITY: VISIONS OF JAMES STREET NORTH, 2005-2011 By VANESSSA E. SAGE, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Vanessa E. Sage, September 2013 PhD Thesis – V. E. Sage McMaster University – Dept. of Anthropology Descriptive Note McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2011) Hamilton, Ontario (Anthropology) TITLE: Arts in the City: Visions of James Street North, 2005-2011 AUTHOR: Vanessa E. Sage, B.A. (Waterloo University), B.A. (Cape Breton University), M.A. (Memorial University of Newfoundland) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Ellen Badone NUMBER OF PAGES: xii, 231 ii PhD Thesis – V. E. Sage McMaster University – Dept. of Anthropology Abstract I argue in this dissertation that aestheticizing urban landscapes represents an effort to create humane public environments in disenfranchised inner-city spaces, and turns these environments into culturally valued sites of pilgrimage. Specifically, I focus on James Street North, a neighbourhood undergoing artistic renewal in the post-industrial city of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Based on two years of ethnographic fieldwork in the arts scene on James Street North, my thesis claims that artistic activities serve as an ordinary, everyday material response to the perceived and real challenges of poverty, crime and decay in downtown Hamilton. Aesthetic elaboration is a generative and tangible expression by arts stakeholders of their intangible hopes, desires, and dreams for the city. -

The Hub of Ontario Trails

Conestoga College (Pulled from below Doon) Cambridge has 3 trails Brantford has 2 Trails Homer Watson Blvd. Doon Three distinct trail destinations begin at Brant’s Crossing Kitchener/Waterloo 47.0 kms Hamilton, Kitchener/ Waterloo Port Dover completes the approximate and Port Dover regions are route on which General Isaac Brock travelled Blair Moyer’s Landing Blair Rd. Access Point Riverside Park now linked to Brantford by during the War of 1812. COUNTY OF OXFORD Speed River 10’ x 15” space To include: No matter your choice of direction, you’ll BRANT’S CROSSING WATERLOO COUNTY a major trail system. WATERLOO COUNTY City of Hamilton logo Together these 138.7 kms of enjoy days of exploration between these Dumfries COUNTY OF BRANT Riverblus Park Conservation Access Point G Area e the Trans Canada Trail provide a variety of three regions and all of the delightful o Tourism - web site or QR code r g e S WATERLOOWATERLOO COUNTYCOUNTY t . towns and hamlets along the way. 401 scenic experiences for outdoor enthusiasts. THETHE HUBHUB OFOF ONTARIOONTARIO TRAILSTRAILS N . Cambridge COUNTY OF WELLINGTON 6 Include how many km of internal trails The newest, southern link, Brantford to 39.8 kms N Any alternate routes Pinehurst Lake Glen Morris Rd. COUNTY OF OXFORD W i t Conservation COUNTY OF BRANT h P Concession St. h Area Cambridge Discover Kitchener / Waterloo Stayovers / accommodations i R Access Point e Churchill i Park Three exciting trail excursions begin in Brantford m v Whether you're biking, jogging or walking, of the city is the Walter Bean Grand River e r Myers Rd.