SACRIFICE, AHIMSA, and VEGETARIANISM: POGROM at the DEEP END of NON-VIOLENCE Volume II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH

NUMBER 46 2017 GAJAHJournal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group Number 46 (2017) The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and conservation of Asian elephants both in the wild and in captivity. It is a means by which everyone concerned with the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), whether members of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group or not, can communicate their research results, experiences, ideas and perceptions freely, so that the conservation of Asian elephants can benefit. All articles published in Gajah reflect the individual views of the authors and not necessarily that of the editorial board or the Asian Elephant Specialist Group. Editor Dr. Jennifer Pastorini Centre for Conservation and Research 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa Julpallama, Tissamaharama Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Dr. Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando School of Geography Centre for Conservation and Research University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Kajang, Selangor Julpallama, Tissamaharama Malaysia Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Varun R. Goswami Heidi Riddle Wildlife Conservation Society Riddles Elephant & Wildlife Sanctuary 551, 7th Main Road P.O. Box 715 Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, 2nd Phase, Kodigehall Greenbrier, Arkansas 72058 Bengaluru - 560 097 USA India e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. T. N. C. Vidya -

Rptmanageenginner

Structural Engineer Details Reg. No. Name Type Resident Address Office Address Mobile No. Reg. Date Validity Date Email ID SD-1/089 Ruwala Kautuk Structural b 408, emerald 403, onyx, nr 9825014690 30-Mar-2017 29-Mar-2022 [email protected] Pradipbhai Engineer residency, nr punjabi hall, rajhans society, navrangpura, gulbai tekra, SD-I/002 Vagadia Virendra Structural 25, Vishvakarma 23, Avani Complex, 9825466860 15-Dec-2018 14-Dec-2023 [email protected] Chandulal Engineer Society,Jivrajpark, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad 380051 Ahmedabad 380009 SD-I/00305 MAHENDRA M Structural 142, HANUMAN FALIYA, 142, HANUMAN 9824144249 12-Aug-2015 11-Aug-2020 [email protected] MISTRY Engineer NR. DABHOLI GARDEN, FALIYA, NR. DABHOLI, SURAT- DABHOLI SD-I/00306 ASHWIN Structural as above 1/6 MARUTINAGAR 9824210151 23-Sep-2015 22-Sep-2020 [email protected] MANILAL Engineer AIRPORT ROAD LODHIYA RAJKOT 36001 SD-I/00307 Himanshu Structural SAKAAR, RSC-4, SAKAAR, RSC-4, 9821111493 28-Sep-2015 27-Sep-2020 [email protected] Madhukar Raje Engineer 391/217A, NEAR BEST 391/217A, NEAR QTRS, SECTOR 1, BEST QTRS, SD-I/00308 Katariya Structural as above 12, Trilok row 9898989577 26-Oct-2015 25-Oct-2020 [email protected] Maheshkumar Engineer house, Opp. Trilok Madhubhai Bunglows, SD-I/00309 GAJJAR Structural A-401, ARJUN A-401, ARJUN 9825625461 12-Jan-2016 11-Jan-2021 [email protected] KRUSHNAKANT Engineer ELEGANCE, OPP. ELEGANCE, OPP. ARVINDKUMAR BHAGIRATH SOCIRTY, BHAGIRATH SD-I/00310 PATEL Structural 19, UMIYANAGAR 19, UMIYANAGAR 8401762260 -

Moral Thinkers Applied Ethics

MP4-Et-19-02 MORAL THINKERS & APPLIED ETHICS Unit-1: Moral Thinkers, Indian Refugees Thinkers & Western Thinkers " Ethical Dilemmas of Globalization " Leaders, Reformers & Moral " Ethics of War Thinkers " Environmental Ethics " Indian Thinkers " Ethical Issues in Biotechnology " Western Thinkers " Animal Ethics " Eminent Administrators & Their " Food Adulteration & Ethics Works " Abortion: Ethical or Unethical Unit-2: Applied Ethics " Honour Killing " Euthanasia Issue " Marital Rape " Surrogacy " Ethical Issue Involved in Child " Ethics & Sports Labour " Media Ethics " Ethical Issue Involved in Treating " Business Ethics Juvenile as Adult " Ethics Related to Economic " Concerns of & Old Age Sanctions " Ethics in Public & Private " Ethical Concerns Related to Relationships TOPICS Contents Moral Thinkers, Indian Thinkers UNIT - 1 & Western Thinkers 1.1 Leaders, Reformers & Moral Thinkers 10-16 1. Fight for Equality ............................................................................10 2. Proposed the Idea of True Freedom ............................................. 12 3. Worked for Maintaining Justice .................................................... 13 4. Worked for Human Resource Development ...............................14 5. Worked for Sustainable Management of Resources .................. 16 1.2 Indian Thinkers 17-24 1. Mahatma Gandhi ............................................................................17 2. Jawaharlal Nehru ...........................................................................19 3. Sardar -

Nidān, Volume 4, No. 2, December 2019, Pp. 151-155 ISSN 2414-8636 151 Book Review Dandekar, Deepra

Nidān, Volume 4, No. 2, December 2019, pp. 151-155 ISSN 2414-8636 Book Review Dandekar, Deepra. (2019) The Subhedar’s Son. A Narrative of Brahmin-Christian Conversion from Nineteenth-century Mahrashtra. New York: Oxford University Press. [ISBN 978-0-19091-405-9] Hard Copy. Pages i-xliv+222. Deepra Dandekar’s annotated translation of The Subhedar's Son, a novel published in 1895 by the Reverend Dinkar Shankar Sawarkar in Marathi as Subhedārachā Putra, is an outstanding contribution to the literature on Hindu conversion to Christianity. The book relates the story of the 1849 conversion of Sawarkar’s father, Shankar Nana (1819-1884), a Brahmin Hindu, at the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in Nasik in northern Maharashtra. The Reverend Nana was an early Brahmin convert of the CMS and served the mission and the Anglican Church for over four decades as a priest, catechist, evangelist and Marathi teacher. His conversion took place at a key historical moment, when power was being transferred from the Maratha Empire to the British administration, and the novel reveals the profound social, cultural and religious changes taking place in Maharashtra around this time. This is a story of an individual conversion but it provides insight more generally into the journey of a Brahmin to conversion, and the experiences of those who were a product of different faiths, caste, and (Marathi) identity, trying to live a Christian life. I could not help but approach this review of Dandekar’s fascinating and insightful study from a South African perspective as so much of it resonates with research being done on Hindu conversions to Christianity (of the Pentecostal variety) in South Africa. -

249 CASE LIST.Xlsx

COVID‐19 POSITIVE CASE 30.04.20 , 8:00 PM S SR NO AGE SEX ADDRESS P E N S SEC 3 /72 VIVEKA NAGAR;HATHIJAN;AHMEDABAD 155MALE / CITY;AHMEDABAD O S N A 13 HARIOM SOC. NEAR RAJEMNDRA 273FEMALE S PARK;ODHAV;AHMEDABAD CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N NARAN PATEL NI CHALI PUNJAB 340MALE S SOC.;ASARWA;AHMEDABAD CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N NARAN PATEL NI CHALI PUNJAB 470MALE S SOC.;ASARWA;AHMEDABAD CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N GRUP 8 GONADAL SRP;DARIYAPUR;AHMEDABAD 531MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N 24 SAURJANY PARK SOC;DANI LIMDA;AHMEDABAD 668MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N VAGRIVAS;PREM DARWAJA;AHMEDABAD 745MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N GROUP 8 GONADAL SRP;DARIYAPUR;AHMEDABAD 824MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N POPATIYA VAD;DARIYAPUR;AHMEDABAD 973MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N BARASING CHALI;SARASPUR;AHMEDABAD 10 45 MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N BOMBAY HOTEL;KESAR PARK GALI NO 11 55 FEMALE S 3;ISANPUR;AHMEDABAD CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N 12 39 FEMALE UTTAM NAGAR;NIKOL;AHMEDABAD CITY;AHMEDABAD S / O N 46 NILKANTH SOC;AMRAIWADI;AHMEDABAD 13 53 FEMALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N 117/2799 GHB COLONY;MEGHANINAGAR;AHMEDABAD 14 52 FEMALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O A‐43 MANILALPARK N 15 40 FEMALE SOC.;NARODA;AHMEDABAD;AHMEDABAD S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N 16 52 FEMALE ARYODAY NAGAR NI CHALI;NARODA;AHMEDABAD S / O N 17 55 FEMALE 10/243 VASANT RAJAK QTS;BEHRAMPURA;AHMEDABAD S / O COVID‐19 POSITIVE CASE 30.04.20 , 8:00 PM S SR NO AGE SEX ADDRESS P E N 18 55 FEMALE KHATKI VAD KHAMASA;LAL DARWAJA;AHMEDABAD S / O N KAZI NA DHABA;ASTODIA;AHMEDABAD 19 70 MALE S CITY;AHMEDABAD / O N 16 A HIGHWAY COMARCIAL CENTAR;DANI 20 36 FEMALE -

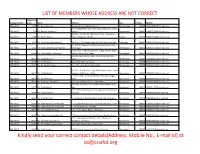

Kindly Send Your Correct Contact Details(Address, Mobile No., E-Mail Id) at [email protected] LIST of MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT

LIST OF MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT Membersh Category Name ip No. Name Address City PinCode EMailID IND_HOLD 6454 Mr. Desai Shamik S shivalik ,plot No 460/2 Sector 3 'c' Gandhi Nagar 382006 [email protected] Aa - 33 Shanti Nath Apartment Opp Vejalpur Bus Stand IND_HOLD 7258 Mr. Nevrikar Mahesh V Vejalpur Ahmedabad 380051 [email protected] Alomoni , Plot No. 69 , Nabatirtha , Post - Hridaypur , IND_HOLD 9248 Mr. Halder Ashim Dist - 24 Parganas ( North ) Jhabrera 743204 [email protected] IND_HOLD 10124 Mr. Lalwani Rajendra Harimal Room No 2 Old Sindhu Nagar B/h Sant Prabhoram Hall Bhavnagar 364002 [email protected] B-1 Maruti Complex Nr Subhash Chowk Gurukul Road IND_HOLD 52747 Mr. Kalaria Bharatkumar Popatlal Memnagar Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] F/ 36 Tarun - Nagar Society Part - 2 Opp Vishram Nagar IND_HOLD 66693 Mr. Vyas Mukesh Indravadan Gurukul Road, Mem Nagar, Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] 8, Keshav Kunj Society, Opp. Amar Shopping Centre, IND_HOLD 80951 Mr. Khant Shankar V Vatva, Ahmedabad 382440 [email protected] IND_HOLD 83616 Mr. Shah Biren A 114, Akash Rath, C.g. Road, Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 84519 Ms. Deshpande Yogita A - 2 / 19 , Arvachin Society , Bopal Ahmedabad 380058 [email protected] H / B / 1 , Swastick Flat , Opp. Bhawna Apartment , Near IND_HOLD 85913 Mr. Parikh Divyesh Narayana Nagar Road , Paldi Ahmedabad 380007 [email protected] 9 , Pintoo Flats , Shrinivas Society , Near Ashok Nagar , IND_HOLD 86878 Ms. Shah Bhavana Paldi Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 89412 Mr. Shah Rajiv Ashokbhai 119 , Sun Ville Row Houses , Mem Nagar , Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] B4 Swetal Park Opp Gokul Rowhouse B/h Manezbaug IND_HOLD 91179 Mr. -

TRULY GLOBAL Worldscreen.Com *LIST 1217 ALT 2 LIS 1006 LISTINGS 11/15/17 2:06 PM Page 2

*LIST_1217_ALT 2_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 11/15/17 2:06 PM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COM DECEMBER 2017 ASIA TV FORUM EDITION TVLISTINGS THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION TRULY GLOBAL WorldScreen.com *LIST_1217_ALT 2_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 11/15/17 2:06 PM Page 2 2 TV LISTINGS ASIA TV FORUM EXHIBITOR DIRECTORY COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR THE COMPANIES IN BOLD CAN BE FOUND IN THIS EDITION OF TV LISTINGS. 9 Story Media Group J30 Fuji Creative Corporation A24-4 Pilgrim Pictures E08/H08 A Little Seed E08/H08 Gala Television Corporation D10 Pixtrend J10 A+E Networks G20 Global Agency E27 Playlearn Media L10 Aardman K32 Globo C30 Premiere Entertainment F34 Aasia Productions E08/H08 GMA Worldwide J01 Primeworks Distribution E30 AB International Distribution E10/F10 Goquest Media Ventures D29 Public Television Service Foundation D10 ABC Commercial L08 Grafizix J10 Rainbow E23 ABC Japan A24-15 Green Gold Animation G30 Rajshri Entertainment L28 About Premium Content E10/F10 Green Yapim N10 Raya Group H07 ABS-CBN Corporation J18 Greener Grass Production D10 Record TV K22 activeTV Asia E08/H08 H Culture J10 Red Arrow International H25 ADK/NAS/D-Rights A24-5 Happy Dog TV L10 Reel One Entertainment K32 AK Entertainment H10/H20 HARI International E10/F10 Refinery Media E08/H08 Alfred Haber Distribution F30 Hasbro Studios F28 Regentact F32 all3media international K08 Hat Trick International K32 Resimli Filim N10 Ampersand E10/F10 Hello Earth B25 Rive Gauche Television J28 Animasia Productions E30 High Commission of Canada H29 RKD Studios L30 Antares International -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Y1 Q2 9-12.Pdf

Balagokulam Syllabus April - June Age Group : 9 to 12 Gokulam is the place where Lord Krishna‛s magical days of childhood were spent. It was here that his divine powers came to light. Every child has that spark of divinity within. Bala- Gokulam is a forum for children to discover and manifest that divinity. It will enable Hindu children in US to appreciate their cultural roots and learn Hindu values in an enjoyable manner. This is done through weekly gatherings and planned activities which include games, yoga, stories, shlokas, bhajan, arts and crafts and much more...... Balagokulam is a program of Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Table of Contents April Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ....................................5 Geet ........................................................................................6 Yugadi ....................................................................................7 Stories of Dr. Hedgewar .......................................................10 The Hindu Calendar .............................................................13 Exercise ................................................................................16 Project / Workshop - Art of Story Telling ............................19 May Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ..................................20 Geet ......................................................................................21 Symbols in Hinduism ...........................................................22 The Life of Buddha ..............................................................26 -

JP Iscon Riverside

https://www.propertywala.com/jp-iscon-riverside-ahmedabad JP Iscon Riverside - Shahibag, Ahmedabad 3 & 4 BHK apartments for sale in JP Iscon Riverside JP Iscon Riverside presented by JP Iscon Group with 3 & 4 BHK apartments for sale in Shahibaug, Ahmedabad Project ID : J811899297 Builder: JP Iscon Group Location: JP River Side, Shahibag, Ahmedabad - 440034 (Gujarat) Completion Date: May, 2016 Status: Started Description JP River Side Woods is a new launch by JP Iscon Group. The project is located in Shahibaug, Ahmedabad. The project offers spacious 3 & 4 BHK apartments in best price. The project is well equipped with all the amenities to facilitate the needs of the residents. Project Details Number of Floors: 1 Number of Units: 7 Amenities Garden 24Hr Backup Security Club House Library Community Hall Swimming Pool Gymnasium Indoor Games JP Iscon Group is today among Gujarat’s pre-eminent real estate developers, with a widespread corporate reputation founded on benchmark performance. The group is famous today for its diverse repertoire of architectural expertise, its inherent streak of innovation, time-conscious planning & execution of projects, and highly evolved skill in property management. Features Luxury Features Security Features Power Back-up Centrally Air Conditioned Lifts Electronic Security Intercom Facility RO System High Speed Internet Wi-Fi Interior Features Recreation Woodwork Modular Kitchen Swimming Pool Fitness Centre / GYM Feng Shui / Vaastu Compliant Club / Community Center Maintenance Land Features Maintenance Staff -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Read Magazine

Trendy Travel Trade with Food & Shop Volume VIII • Issue I • February 2021 • Pages 88 • Rs.100/- Experience Spirituality, Faith and Culture #LadyBoss Kutch: A Land of White Desert Royal Journey of India Archaeological Tour of Majestic Kerala Enchanting Himalayas Tribal Trail Buddhist Temple with 18 to 20 Nights Rajasthan 14 to 15 Nights with Taj 15 to 17 Nights North East India Tour Mumbai – Mangalore – Bekal – Wayanad Bhubaneswar - Dangmal - Bhubaneswar 21 to 23 Nights 13 to 15 Nights 14 to 16 Nights Delhi - Jaipur - Pushkar – Ranthambore – Kozhikode(Calicut) - Baliguda Delhi – Jaipur – Samode – Nawalgarh – Delhi - Agra - Darjeeling - Gangtok - Delhi - Varanasi -Bodhgaya - Patna Sawai Madhopur – Kota – Cochin – Thekkady – Kumarakom– - Rayagada - Jeypore - Rayagada - Bikaner – Gajner – Jaisalmer – Osian Phuntsholing - Thimphu - Punakha - -Kolkata - Bagdogara - Darjeeling - Bundi - Chittorgarh - Bijaipur - Quilon – Varkala – Kovalam Gopalpur - Puri – Bhubaneswar Udaipur - Kumbalgarh - Jodhpur - – Khimsar – Manvar – Jodhpur – Rohet – Paro - Delhi - Pelling (Pemayangtse)- Gangtok - Jaisalmer - Bikaner - Mandawa – Delhi Mount Abu – Udaipur – Dungarpur Kalimpong -Bagdogra – Delhi – Deogarh – Ajmer – Pushkar – Pachewar – Ranthambhore – Agra – Delhi Contact @ :+91- 9899359708, 9999683737, info@ travokhohlidays.com, [email protected], www.travok.net EXPERIENCEHingolga HERITAGE & NATURE ATdh ITS BEST A Hidden Gem of Gujarat Just 70 kms away from Rajkot is a unique sanctuary which not only offers the grandeur of a royal era but also nature's treasures. Explore the magnicent Hingolgadh palace surrounded by a scenic sanctuary that is home to the Chinkara, Wolf, Jackal, Fox, Porcupine, Hyena, Indian Pitta and 230 species of birds. So this weekend, have a royal experience and some wild adventure. Disclaimer: The details and pictures contained here are for information and could be indicative.