Inside Newfoundland's Craft Beer Boom by Natalie Dignam a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

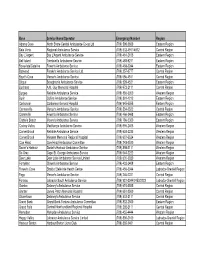

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Constituency Allowance 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Constituency Allowance 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 MICHAEL, LORRAINE, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $2,609.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $281.05 Funds Available (Net of HST): $2,327.95 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 10.8% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 05-Apr-18 MECMS1037289 Seniors NL Description: Dinner with Constituents 35.09 19-Apr-18 MECMS1037289 Bishop Field School Description: dinner with Constituents 46.26 03-Dec-18 MECMS1060515 Belbins Description: Drinks for a Constitueny gathering - Challker Place Community 99.70 Centre 19-Feb-19 MECMS1067054 CSC NL Description: Annual Volunteerism Luncheon 56.14 08-Mar-19 MECMS1067054 PSAC Description: International Womens Day Luncheon 43.86 Period Activity: 281.05 Opening Balance: 0.00 Ending Balance: 281.05 ---- End of Report ---- House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Travel & Living Allowances - Intra & Extra-Constituency Travel 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 MICHAEL, LORRAINE, MHA Page: 1 of 2 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $5,217.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $487.74 Funds Available (Net of HST): $4,729.26 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 9.3% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 12-Apr-18 MECMS1037633 I&EConst Priv Vehicle Usage - Description: Confederation Building to Mt Pearl - 11.00 return 13-Apr-18 MECMS1037633 I&EConst Priv Vehicle Usage - Description: Confederation Building - Quidi - Vidi 5.18 - return 17-Apr-18 MECMS1037633 I&EConst Priv Vehicle Usage - Description: Mt. -

Study of Proposed Amendments to Canada's Beer Standard of Identity

Study of Proposed Amendments to Canada’s Beer Standard of Identity Report prepared by Beer Canada’s Product Quality Committee October 2013 Authors Bill Andrews Ludwig Batista Manager, Brewing Quality National Technical Director Molson Coors Canada Sleeman Breweries Ltd. [email protected] [email protected] Ian Douglas (Committee Chair) Dr. Terry Dowhanick Global Director, Quality and Food Safety Quality Assurance and Product Integrity Manager Molson Coors Canada Labatt Breweries of Canada [email protected] [email protected] Anita Fuller Brad Hagan Quality Services Manager Director of Brewing Operations Great Western Brewing Company Labatt Breweries of Canada [email protected] [email protected] Peter Henneberry Dave Klaassen Adviser Vice President, Operations Moosehead Breweries Ltd. Sleeman Breweries Ltd. [email protected] [email protected] Russell Tabata Luke Harford Chief Operating Officer President Brick Brewing Co. Limited Beer Canada [email protected] [email protected] Luke Chapman Manager, Economic and Technical Affairs Beer Canada [email protected] 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 2.0 The Canadian Brewing Industry .............................................................................................................. 5 3.0 Historical Context of the Standard ......................................................................................................... -

Quick Report

Quick Report Average Quiz Score Total Responses Average Score Max Points Attainable Average Percentage Who was the first Prime Minister of Canada? 82 0.98 1 97.56% What is the most popular sport in Canada? 81 0.95 1 95.06% What two animals are featured on the Canadian Coat of Arms? 81 0.48 1 48.15% What is the largest City in Canada? 81 0.95 1 95.06% What is the national animal of Canada? 81 0.98 1 97.53% True or false- the origin of the name Canada is derived from the Huron-Iroquois word, Kanata, meaning a village or settlement? 81 0.96 1 96.30% What are french fries, gravy and cheese curds called? 81 0.99 1 98.77% Wood Buffalo National Park has the world's longest 81 0.79 1 79.01% What percentage of all the alcohol consumed in Canada is Beer? 80 0.50 1 50.00% How many countries are larger geographically than Canada? 80 0.65 1 65.00% What is the best selling beer in Canada? 77 0.21 1 20.78% What percentage of the world's fresh water is in Canada? 78 0.42 1 42.31% Who is the Head of State of Canada? 78 0.63 1 62.82% What was launched in 1936 to unify our sprawling Country? 77 0.38 1 37.66% True or False - Laura Secord warned the British of an impending attack on Canada by the Americans during the war of 1812 and because of this won t… 77 0.86 1 85.71% What is an Inukshuk? 77 0.95 1 94.81% 50% of the world's population of this animal live in Canada? 76 0.49 1 48.68% What is the most popular coffee chain in Canada? 76 0.97 1 97.37% What animal is on the Quarter? 76 0.64 1 64.47% What was the name of the system of safe passages and safe houses that allowed American slaves to escape to freedom in Canada? 76 0.87 1 86.84% Canada produces 80% of the world's supply of what? 75 0.77 1 77.33% What is slang for Canadian? 75 0.77 1 77.33% What is the most recent territory in Canada called? 75 0.92 1 92.00% Please enter in your contact information to be entered to win the Canada 150 prize packFirst name and phone # or email 68 0.00 0 0% Total: 82 16.38 23 71.21% Who was the first Prime Minister of Canada? Paul Martin John Diefenbaker John A. -

Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada

MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2013 Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada Source: Planet Retail, 2012. Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE Canada’s population, estimated at nearly 34.9 million in 2012, Executive Summary 2 has been gradually increasing and is expected to continue doing so in the near-term. Statistics Canada’s medium-growth estimate for Canada’s population in 2016 is nearly 36.5 million, Market Trends 3 with a medium-growth estimate for 2031 of almost 42.1 million. The number of households is also forecast to grow, while the Wine 4 unemployment rate will decrease. These factors are expected to boost the Canadian economy and benefit the C$36.8 billion alcoholic drink market. From 2011 to 2016, Canada’s economy Beer 8 is expected to continue growing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2% and 3% (Euromonitor, 2012). Spirits 11 Canada’s provinces and territories vary significantly in geographic size and population, with Ontario being the largest 15 alcoholic beverages market in Canada. Provincial governments Distribution Channels determine the legal drinking age, which varies from 18 to 19 years of age, depending on the province or territory. Alcoholic New Product Launch 16 beverages must be distributed and sold through provincial liquor Analysis control boards, with some exceptions, such as in British Columbia (B.C.), Alberta and Quebec (AAFC, 2012). New Product Examples 17 Nationally, value sales of alcoholic drinks did well in 2011, with by Trend 4% growth, due to price increases and premium products such as wine, craft beer and certain types of spirits. -

St. John's Sustainable Living Guide

St. John’s Sustainable Living Guide This sustainable living guide is the product of a class project for Geography 6250 at Memorial University, a graduate course on the conservation and sustainability of natural resources. It was designed by the class for the public of St. John’s. We would like to acknowledge Ratana Chuenpagdee (course professor) and Kelly Vodden (Geography Professor) for their guidance, comments and support. We would also like to thank the MMSB, and particularly Catherine Parsons (Marketing and Public Education Officer) for information about recycling programs in St. John’s. We would especially like to acknowledge Toby Rowe (Memorial University Sustainability Coordinator) for the interest in this work and for inviting us to display the guide on the MUN Sustainability Office Website. For more information about sustainability initiatives at Memorial University please visit www.mun.ca/sustain. Contributors: Amy Tucker Christina Goldhar Alyssa Matthew Courtney Drover Nicole Renaud Melinda Agapito Hena Alam John Norman Copyright © International Coastal Network, 2009 Recommended Citation: Tucker, A., Goldhar, C., Matthew, A., Drover, C., Renaud, N., Agapito, M., Alam, H., & Norman, J. 2009. St. John’s Sustainable Living Guide. Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, 40 p. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the above contributors. Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Sustainable Landscaping……………………………………………………………………………………………..2-4 Sustainable -

• Articles • Becoming Local

PAGE 44 • Articles • Becoming Local: The Emerging Craft Beer Industry in Newfoundland, Canada NATALIE DIGNAM Memorial University of Newfoundland Abstract: This article considers the ways craft breweries integrate the local culture of Newfoundland, Canada in their branding, events and even flavors. Between 2016 and 2019, the number of craft breweries in Newfoundland quadrupled. This essay examines how this emerging industry frames craft beer as local through heritage branding that draws on local customs and the island's unique language. At the same time, some breweries embrace their newness by reinterpreting representations of rural Newfoundland. In May of 2017, I moved from Massachusetts to the island of Newfoundland with my husband. "The Rock," as it's nicknamed, part of Canada's easternmost province of Newfoundland and Labrador, is an isolated island of over 155,000 square miles of boreal forest, bluffs and barrens. During that first summer, we were enthralled by the East Coast Trail, a hiking trail that loops around the Avalon Peninsula on the eastern edge of the island. From rocky cliffs, we spotted whales, hawks, icebergs, and seals. We often ate a "feed of fish and chips," as I have heard this popular dish called in Newfoundland. One thing we missed from home were the numerous craft breweries, where we could grab a pint after a day of hiking. We had become accustomed to small, locally-owned breweries throughout New England, operating out of innocuous locations like industrial parks or converted warehouses, where we could try different beers every time we visited. I was disappointed to find a much more limited selection of beer when I moved to Newfoundland. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 91 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2016 No. 43 GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD ACT NOTICE UNDER THE AUTHORITY of subsection 6(1), of the Geographical Names Board Act, RSNL1990 cG-3, the Minister of the Department of Municipal Affairs, hereby approves the names of places or geographical features as recommended by the NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD and as printed in Decision List 2016-01. DATED at St. John's this 19th day of October, 2016. EDDIE JOYCE, MHA Humber – Bay of Islands Minister of Municipal Affairs 337 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE October 28, 2016 Oct 28 338 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE October 28, 2016 MINERAL ACT DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES JUSTIN LAKE NOTICE Manager - Mineral Rights Published in accordance with section 62 of CNLR 1143/96 File #'s 774:3973; under the Mineral Act, RSNL1990 cM-12, as amended. 775:1355, 3325, 3534, 3614, 5056, 5110 Mineral rights to the following mineral licenses have Oct 28 reverted to the Crown: URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING ACT, 2000 Mineral License 011182M Held by Maritime Resources Corp. NOTICE OF REGISTRATION Situate near Indian Pond, Central NL TOWN OF CARBONEAR On map sheet 12H/08 DEVELOPMENT REGULATION AMENDMENT NO. 33, 2016 Mineral License 017948M Held by Kami General Partner Limited TAKE NOTICE that the TOWN OF CARBONEAR Situate near Miles Lake Development Regulations Amendment No. 33, 2016, On map sheet 23B/15 adopted on the 20th day of July, 2016, has been registered by the Minister of Municipal Affairs. -

FROM FARM to GLASS: the Value of Beer in Canada

FROM FARM TO GLASS: The Value of Beer in Canada Glen Hodgson Chief Economist and Senior Vice President, The Conference Board of Canada November 5, 2013 conferenceboard.ca Economic Footprint of Beer. • Report investigates size and scope of beer economy. • Breweries are a large manufacturing industry, but there is more to the story. • Beer has a long supply chain and is retailed in stores and consumed in bars, and restaurants. • Therefore, beer’s contribution to Ca n adi an GDP i s m uch larger than brewers themselves. 2 Beer is the preferred alcohol choice. (volume of Canadian sales in absolute alcohol content; millions of litres) Spirits Wine Beer 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Sources: Statistics Canada; The Conference Board of Canada. 3 Putting the industry into perspective. Canadian breweries industry: • Smaller than forestry and logging • About the same size as the postal service • Larger than wineries and distilleries, soft drink manufacturing, and many others. 4 Putting the industry into perspective. (2012 real GDP for selected Canadian industries; 2007 $ millions) Forestry and logging 3,729 Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing 3,451 Postal service 3,179 Breweries 3,166 Radio and television broadcasting 3,081 Dairy product manufacturing 2, 866 Coal mining 1,666 Soft drink and ice manufacturing 1,168 Fishing, hntinghunting, and trapping 1, 127 Wineries and distilleries 889 Sources: Statistics Canada; The Conference Board of Canada. 5 What is the “Beer Economy”? It’s more than just breweries… When you drink a bottle of beer, you support: 1. Direct Impacts: The brewing industry 2. Supply Chain Impacts: 6 What is the “Beer Economy”? It’s more than just breweries… 3. -

(PL-557) for NPA 879 to Overlay NPA

Number: PL- 557 Date: 20 January 2021 From: Canadian Numbering Administrator (CNA) Subject: NPA 879 to Overlay NPA 709 (Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada) Related Previous Planning Letters: PL-503, PL-514, PL-521 _____________________________________________________________________ This Planning Letter supersedes all previous Planning Letters related to NPA Relief Planning for NPA 709 (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada). In Telecom Decision CRTC 2021-13, dated 18 January 2021, Indefinite deferral of relief for area code 709 in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) approved an NPA 709 Relief Planning Committee’s report which recommended the indefinite deferral of implementation of overlay area code 879 to provide relief to area code 709 until it re-enters the relief planning window. Accordingly, the relief date of 20 May 2022, which was identified in Planning Letter 521, has been postponed indefinitely. The relief method (Distributed Overlay) and new area code 879 will be implemented when relief is required. Background Information: In Telecom Decision CRTC 2017-35, dated 2 February 2017, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) directed that relief for Newfoundland and Labrador area code 709 be provided through a Distributed Overlay using new area code 879. The new area code 879 has been assigned by the North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) and will be implemented as a Distributed Overlay over the geographic area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador currently served by the 709 area code. The area code 709 consists of 211 Exchange Areas serving the province of Newfoundland and Labrador which includes the major communities of Corner Brook, Gander, Grand Falls, Happy Valley – Goose Bay, Labrador City – Wabush, Marystown and St. -

4. Key Organic Foods

16 |ORGANIC FOOD PROCESSING IN CANADA Table 4.2. Top Canadian processed organic foods and 4. Key organic foods beverages by number of processors Processed Product Number of In this section, we examine major organic food types Processors in order of sales value. Beverages led organic sales Maple products 227 in 2017 (Table 4.1). Non-alcoholic beverages ranked Non alcoholic beverages 184 first in overall sales, while dairy was the largest selling Baked goods 138 food segment, followed by bakery products and ready Fruits & vegetables 98 meals. Maple products were the number one product Meat products 92 processed by Canadian organic processors (227 Dairy products 71 processors), followed by non-alcoholic beverages Snack foods 70 (184), baked goods (138), fruit and vegetable products Edible oils 55 (98) and meat (88) (Table 4.2). Sauces, dressings & condiments 39 Alcoholic beverages 37 Table 4.1 Top organic packaged foods sold at retail in Breakfast cereals 35 2017, $CAN millions Spreads 28 Processed Product Value Rice & pasta 27 Non alcoholic beverages 779.0 Ready meals 23 Dairy 377.6 Soup 16 Bakery products 237.4 Aquaculture products 8 Alcoholic beverages 230.0 Baby food 6 Ready meals 192.3 Breakfast cereals 132.3 Canadian retail sales values for each of the types Processed fruits/vegetables 86.4 of non-alcoholic beverages are shown in Table 4.3. Snacks 72.6 There were 184 organic non-alcoholic beverage man- Baby food 68.0 ufacturers in 2018, with the majority located in ON. Table 4.4 shows the number of manufacturers for each Meat 64.3 non-alcoholic beverage type. -

Regional News

REGIONAL FIS E IES NEWS J liaRY 1970 ( 1 • Mdeit,k40 111.111111111...leit 9 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES OF CANADA NEWFOUNDLAND REGION REDUCTION PLANT OFFICIALLY OPENED The ne3 3/4-million NATLAKE herring reduction plant at Burgeo was officially opened January 28th by Premier J. R. Smallwood. Among special guests attending the opening ceremonies were: federal Transport Minister Don Jamieson, provincial Minister of Fisheries A. Maloney and our Regional Director, H. R. Bradley. Privately financed, the new plant is a joint effort of Spencer Lake, the Clyde Lake Group and National Sea Products of Nova Scotia. Ten herring seiners from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and British Columbia are under contract to land catches at the plant. Fifty people will be employed as production workers at the plant which will operate on a 21-hour, three shift basis. - 0 - 0 - 0 - ATTEND CAMFI CONFERENCE Four representatives of Regional Headquarters staff are attending the Conference on Automation and Mechanization in the Fishing Industry being held in Montreal February 3 - 6. The conference is sponsored by the Federal-Provincial Atlantic Fisheries Committee which is comprised of the deputy ministers responsible for fisheries in the Federal Government and the governments of Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The Secretariat for the conference was provided by the Industrial Development Service, Department of Fisheries and Forestry, Ottawa. Attending the conference from the Newfoundland. Region were: J. P. Hennessey, R. n. Prince, m. Barnes and E. B. Dunne. ****** ****** FROZEN TROUT RETURN TO LIFE A true story told by Bob Ebsary, a former technician with our Inspection Laboratory, makes one wonder whether or not trout, like cats, have nine lives.