The Ojibwa Dance Drum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roosevelts' Giant Panda Group Installed in William V

News Published Monthly by Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago Vol. 2 JANUARY, 1931 No. 1 ROOSEVELTS' GIANT PANDA GROUP INSTALLED IN WILLIAM V. KELLEY HALL By Wilfred H. Osgood conferences with them at Field Museum be superficial, and it was then transferred Curator, Department of Zoology while the expedition was being organized, to the group which includes the raccoons although it was agreed that a giant panda and allies, one of which was the little panda, The outstanding feature of the William would furnish a most satisfactory climax for or common which is also Asiatic in V. Kelley-Roosevelts Expedition to Eastern panda, their the chance of one was distribution. Still an Asia for Field Museum was the obtaining efforts, getting later, independent posi- considered so small it was best to tion was advocated for in which it became of a complete and perfect specimen of the thought it, make no announcement it when the sole of a peculiar animal known as the giant panda concerning living representative distinct or great panda. In popular accounts this they started. There were other less spec- family of mammals. Preliminary examina- rare beast has been described as an animal tacular animals to be hunted, the obtaining tion of the complete skeleton obtained by with a face like a raccoon, a body like a of which would be a sufficient measure of the Roosevelts seems to indicate that more bear, and feet like a cat. Although these success, so the placing of advance emphasis careful study will substantiate this last view. characterizations are The giant panda is not scientifically accu- a giant only by com- rate, all of them have parison with its sup- some basis in fact, and posed relative, the little it might even be added panda, which is long- that its teeth have cer- tailed and about the tain slight resem- size of a small fox. -

Down Come the Prices on a Hest of Splendid Things!T

7va fi' v1 v, X-i- ' t - .e 4mm Baihd sit 9 and 5:20; Organ WEATHER at 11 Stere Opens at 9 Stere Closes at 5:30 Chlmea at Ncren WANAMAKER'S WANAMAKER'S WANAMAKER'S Fair Down Come the Prices On a Hest of Splendid Things!t r Net "as Little as We Can, But Monday as Much as We Dare" Hanging Lamps and Wall Ready Morning With is our own transposition of Bishop Wescott's words applicable te every Fixtures All Lowered in Price Mere Than $200,000 Werth honest undertaking and mutual help- A Brilliant Opportunity - fulness. of Men's and Women's Shoes Mere $20,000 of hanging fixtures side brackets Nene of us has finished his education than worth and and graduated from the high schools of for electric lights have just had their prices lowered. in a Most Unusual Sale faithful endeavor. 4 Yeu can equip your dining room or living room with new wall The price of shoes is one of Tomorrow's day should count up brackets all around; you can get new hanging-lam-p fixtures for the the greatest items of interest of mere than today's best day. Put en your thinking cap net te table that the family gathers about. the day. make a mere spurt, but te be your real, Instead of going te a manufacturer's and looking at a sample There is an immense amount best, steady sell. and waiting months te have them made up, you can come in here of speculation as te when they and get them and have them sent home at once and save money. -

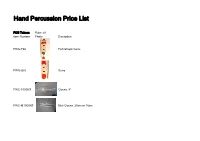

Hand Percussion Price List

Hand Percussion Price List FOB Taiwan Rate: 29 Item Number Photo Discription PWG-F86 Fish Shape Guiro PWG-S83 Guiro PWC-1000NT Claves, 8" PWC-M1000NT Mini Claves, 20cm or 18cm PWBG-T2 Two Tone Wood Block Scraper PWKH-RD Wooden Handle Castanet PWBG-1 Single Guiro Tone Block PSS-CC Coconut Shaker YD0-2H5A2 Drum Sticks, Hickory YD0-2M5A2 Drum Sticks, Maple YD0-2O5A Drum Sticks, Oak YD0-2H5AF(GR) Drum Sticks, Hickory, Fluorescent, 2-color YD0-2TB Timbale Sticks YD0-2RASBK Rods, anti-slip ORS-3111PU Recorder, Purple Transparent ORS-3111BL Recorder, Blue Transparent ORS-3111YE Recorder, Yellow Transparent ORS-3111OR Recorder, Orange Transparent ORS-3111GR Recorder, Green Transparent ORS-32BR Recorder, Brown ORS-32CR Recorder, Creamed Colored ORS-3221IB Recorder, Creamed Colored / Brown ORS-32PB Recorder, Pink / Light Blue PBS-H25 Sleigh Bell, 25 Bells PBS-H25B Sleigh Bell, 25 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M24 Mounted Sleigh Bell, 24 Bells PBS-M24B Mounted Sleigh Bell, 24 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-H13 Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells PBS-H13B Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-H12 Sleigh Bell, 12 Bells PBS-M12 Mounted Sleigh Bell, 12 Bells PBS-M9 Sleigh Bell, 9 Bells PBS-M9B Sleigh Bell, 9 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M7 Sleigh Bell, 7 Bells PBS-M7B Sleigh Bell, 7 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M5 Sleigh Bell, 5 Bells PBS-M5B Sleigh Bell, 5 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M4 Sleigh Bell, 4 Bells PBS-M4B Sleigh Bell, 4 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-H3 Sleigh Bell, 3 Bells PBS-H3B Sleigh Bell, 3 Bells (Brass Bell) PBS-M13 Mounted Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells PBS-M13B Mounted Sleigh Bell, 13 Bells -

MVP Packet 7.Pdf

Musical Visual Packet A tournament by the Purdue University Quiz Bowl Team Questions by Drew Benner, John Petrovich, Patrick Quion, Andrew Schingel, Lalit Maharjan, Pranav Veluri, and Ben Dahl ROUND 7: Finale 1) In a musical production choreographed by John Heginbotham, this scene introduces an electric guitar to the acoustic score and during it, boots fall from the rafters one by one. Gabrielle Hamilton stars in this scene in a revival that has it performed by a single dancer, barefoot, in a modern style. The film version of this scene has a tornado roaring in the background, while Susan Stroman’s choreography for this scene has the main cast perform it themselves, instead of having trained dancers play (*) avatars of them. This sequence occurs after a character consumes the “Elixir of Egypt,” and it begins with a cheerful wedding that changes tone when the bride realizes two men have suddenly switched characters. Originally choreographed by Agnes de Mille, this revolutionary scene is regarded as the first dance sequence in a musical to incorporate plot. For ten points, name this fantasy sequence from a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, where Laurey struggles choosing between Jud and Curly after taking a sleeping drug. ANS: the dream ballet from Oklahoma! (prompt on partial, ask for “from what musical” if just dream ballet is given) <Musicals | Quion> 2) For one show, this composer created polyphonic chants in the fictional Zentraedi language and songs for the pop star Sharon Apple. Sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder, famous for recording albums like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, recorded this composer’s tracks for their most famous show. -

A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments Xiaoling Wang, Xiaoling Wu Changji University Changji, Xinjiang, China Keywords: Uygur Musical Instruments, Origin, Evolution, Research Status Abstract: There Are Three Opinions about the Origin of Uygur Musical Instruments, and Four Opinions Should Be Exact. Due to Transliteration, the Same Musical Instrument Has Multiple Names, Which Makes It More Difficult to Study. So Far, the Origin of Some Musical Instruments is Difficult to Form a Conclusion, Which Needs to Be Further Explored by People with Lofty Ideals. 1. Introduction Uyghur Musical Instruments Have Various Origins and Clear Evolution Stages, But the Process is More Complex. I Think There Are Four Sources of Uygur Musical Instruments. One is the National Instrument, Two Are the Central Plains Instruments, Three Are Western Instruments, Four Are Indigenous Instruments. There Are Three Changes in the Development of Uygur Musical Instruments. Before the 10th Century, the Main Musical Instruments Were Reed Flute, Flute, Flute, Suona, Bronze Horn, Shell, Pottery Flute, Harp, Phoenix Head Harp, Kojixiang Pipa, Wuxian, Ruan Xian, Ruan Pipa, Cymbals, Bangling Bells, Pan, Hand Drum, Iron Drum, Waist Drum, Jiegu, Jilou Drum. At the Beginning of the 10th Century, on the Basis of the Original Instruments, Sattar, Tanbu, Rehwap, Aisi, Etc New Instruments Such as Thar, Zheng and Kalong. after the Middle of the 20th Century, There Were More Than 20 Kinds of Commonly Used Musical Instruments, Including Sattar, Trable, Jewap, Asitar, Kalong, Czech Republic, Utar, Nyi, Sunai, Kanai, Sapai, Balaman, Dapu, Narre, Sabai and Kashtahi (Dui Shi, or Chahchak), Which Can Be Divided into Four Categories: Choral, Membranous, Qiming and Ti Ming. -

…But You Could've Held My Hand by Jucoby Johnson

…but you could’ve held my hand By JuCoby Johnson Characters Eddie (He/Him/His)- Black Charlotte/Charlie (They/Them/Theirs)- Black Marigold (She/Her/Hers)- Black Max (He/Him/His)- Black Setting The past and present. Author’s Notes Off top: EveryBody in this play is Black. I strongly encourage anyone casting this play to avoid getting bogged down in a narrow understanding of blackness or limit themselves to their own opinions on what it means to be black. Consider the full spectrum of Blackness and what you will find is the full spectrum of humanity. One character in this play is gender non-binary. I encourage people to fill the role with an actor who is also gender non-binary. I also urge people not to stop there. Consider trans performers for any and all roles. This play can only benefit from their presence in the room. The ages of the actors don’t need to match the ages of the characters. I would actually encourage an ensemble of all different ages. As we play with time in this play, this will open us up to possibilities that extend beyond realism or any other genre. Speaking of genre, my only request is that the play be theatrical. Whatever that means to you. This is not realism, or naturalism, or expressionism, or any other ism. Forget all about genre. All that to say: Be Bold. Have fun. Lead with love. 2 “Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.” -Toni Morrison 3 A Beginning Darkness. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Arm Aitor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 V,: "he dreamed of dancing with the blue faced people ..." (Hosteen Klah in Paris 1990: 178; photograph by Edward S. Curtis, courtesy of Beautyway). THE YÉ’II BICHEII DANCING OF NIGHTWAY: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF DANCE IN A NAVAJO HEALING CEREMONY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sandra Toni Francis, R.N., B.A., M. -

Living Culture Embodied: Constructing Meaning in the Contra Dance Community

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2011 Living Culture Embodied: Constructing Meaning in the Contra Dance Community Kathryn E. Young University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Young, Kathryn E., "Living Culture Embodied: Constructing Meaning in the Contra Dance Community" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 726. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/726 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. LIVING CULTURE EMBODIED: CONSTRUCTING MEANING IN THE CONTRA DANCE COMMUNITY __________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Kathryn E. Young August 2011 Advisor: Dr. Christina F. Kreps ©Copyright by Kathryn E. Young 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Kathryn E. Young Title: LIVING CULTURE EMBODIED: CONSTRUCTING MEANING IN THE CONTRA DANCE COMMUNITY Advisor: Dr. Christina F. Kreps Degree Date: August 2011 Abstract In light of both the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and the efforts of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage in producing the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, it has become clear that work with intangible cultural heritage in museums necessitates staff to carry out ethnographic fieldwork among heritage communities. -

Nelly, TLC, and Flo Rida Have Announced That They Will Be Hitting the Road Together for an Epic Tour Across North America

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Bridget Smith v.845.583.2179 Photos & Interviews may be available upon request [email protected] NELLY, TLC AND FLO RIDA ANNOUNCE SUMMER AMPHITHEATER TOUR; INCLUDES PERFORMANCE AT BETHEL WOODS ON FRIDAY, AUGUST 9TH Tickets On-Sale Friday, March 15th at 10 AM March 11, 2019 (BETHEL, NY) – Music icons Nelly, TLC, and Flo Rida have announced that they will be hitting the road together for an epic tour across North America. The Billboard chart-topping hit makers will join forces to bring a show like no other to outdoor amphitheater stages throughout the summer – including a performance at Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, at the historic site of the 1969 Woodstock festival in Bethel, NY, on Friday, August 9th. Fans can expect an incredible, non-stop party with each artist delivering hit after hit all night long. Tickets go on sale to the general public beginning Friday, March 15th at 10 AM local time at www.BethelWoodsCenter.org, www.Ticketmaster.com, Ticketmaster outlets, or by phone at 1.800.745.3000. Citi is the official presale credit card for the tour. As such, Citi card members will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, March 12th at 12 PM local time until Thursday, March 14th at 10 PM local time through Citi’s Private Pass program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. About Nelly: Nelly is a Diamond Selling, Multi-platinum, Grammy award-winning rap superstar, entrepreneur, philanthropist and TV/Film actor. Within the United States, Nelly has sold in excess of 22.5 million albums; on a worldwide scale, he has been certified gold and/or platinum in more than 35 countries – estimates bring his total record sales to over 40 Million Sold. -

EVANS-DISSERTATION.Pdf (2.556Mb)

Copyright by Katherine Liesl Young Evans 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Katherine Liesl Young Evans certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Staged Encounters: Native American Performance between 1880 and 1920 Committee: James H. Cox, Supervisor John M. González Lisa L. Moore Gretchen Murphy Deborah Paredez Staged Encounters: Native American Performance between 1880 and 1920 by Katherine Liesl Young Evans, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2010 Acknowledgements For someone so concerned with embodiment and movement, I have spent an awful lot of the last seven years planted in a chair reading books. Those books, piled on my desk, floor, and bedside table, have variously angered, inspired, and enlightened me as I worked my way through this project, but I am grateful for their company and conversation. Luckily, I had a number of generous professors who kept funneling these books my way and enthusiastically discussed them with me, not least of which were the members of my dissertation committee. James Cox, my director, offered unflagging enthusiasm and guidance and asked just the right questions to push me into new areas of inquiry. Lisa Moore, Gretchen Murphy, John González, and Deborah Paredez lit the way towards this project through engaging seminars, lengthy reading lists, challenging comments on drafts, and crucial support in the final stages. Other members of the English department faculty made a substantial impact on my development as a teacher and scholar. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Your Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Powvwows

Indian Education for All Your Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Pow Wows Thanks to: Murton McCluskey, Ed.D. Revised January 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................... 1 History of the Pow Wow ............................................... 2-3 The Pow Wow Committee ............................................ 4 Head Staff ............................................................. 4 Judges and Scoring................................................ 4-6 Contest Rules and Regulations ................................... 7 Singers..................................................................... 7 Dancers................................................................... 8 The Grand Entry................................................... 8 Pow Wow Participants.......................................... 9 The Announcer(s) ................................................ 9 Arena Director....................................................... 9 Head Dancers......................................................... 9 The Drum, Songs and Singers..................................... 10 The Drum...............................................................10 Singing..................................................................... 10-11 The Flag Song........................................................ 12 The Honor Song.................................................... 12 The Trick Song.......................................................12 Dances and Dancers.......................................................