Causes of Groundwater Depletion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Porosity and Permeability Lab

Mrs. Keadle JH Science Porosity and Permeability Lab The terms porosity and permeability are related. porosity – the amount of empty space in a rock or other earth substance; this empty space is known as pore space. Porosity is how much water a substance can hold. Porosity is usually stated as a percentage of the material’s total volume. permeability – is how well water flows through rock or other earth substance. Factors that affect permeability are how large the pores in the substance are and how well the particles fit together. Water flows between the spaces in the material. If the spaces are close together such as in clay based soils, the water will tend to cling to the material and not pass through it easily or quickly. If the spaces are large, such as in the gravel, the water passes through quickly. There are two other terms that are used with water: percolation and infiltration. percolation – the downward movement of water from the land surface into soil or porous rock. infiltration – when the water enters the soil surface after falling from the atmosphere. In this lab, we will test the permeability and porosity of sand, gravel, and soil. Hypothesis Which material do you think will have the highest permeability (fastest time)? ______________ Which material do you think will have the lowest permeability (slowest time)? _____________ Which material do you think will have the highest porosity (largest spaces)? _______________ Which material do you think will have the lowest porosity (smallest spaces)? _______________ 1 Porosity and Permeability Lab Mrs. Keadle JH Science Materials 2 large cups (one with hole in bottom) water marker pea gravel timer yard soil (not potting soil) calculator sand spoon or scraper Procedure for measuring porosity 1. -

Hydrogeology of Flowing Artesian Wells in Northwest Ohio

Hydrogeology of Flowing Artesian Wells in Northwest Ohio By Curtis J Coe, CPG and Jim Raab Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Resources June 2016 Bulletin 48 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Site Location and Setting .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 ODH Water Well Regulations for Flowing Artesian Wells ............................................. 3 1.3 Purpose and Scope of Work .............................................................................................. 3 2.0 Previous Work ....................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Bedrock Hydrogeology ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Glacial Hydrogeolgy ......................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1 Williams Complex Aquifer ....................................................................................... 8 2.2.2 Williams End Moraine Aquifer ................................................................................. 8 2.2.3 Buried Valley Aquifers ............................................................................................ 13 2.2.4 Lake Maumee Lacustrine Aquifer .......................................................................... -

Do You Drink It? 9-12

DO YOU DRINK IT? 9-12 SUBJECTS: Science (Physical Science, Ecology, Earth Science), Social Studies (Geography) TIME: 2 class periods MATERIALS: 3-liter soda bottles aquarium gravel sand (coarse) pump from liquid dispenser blue, yellow & Red food coloring paper cups straws student sheets droppers scissors or razor blades markers OBJECTIVES The student will do the following: 1. Create an aquifer model. 2. Locate major U.S. aquifers. 3. Explain how a well works. 4. Examine a well’s relationship to the water table. 5. Apply principles of well placement. 6. Explain different ways that groundwater is contaminated. 4-37 BACKGROUND INFORMATION An aquifer is an underground layer of rock or soil that holds the water called groundwater. The word “aquifer” is derived from the Latin “aqua” meaning “water ,”and “ferre” meaning “to bring” or “to yield.” The ability of a geological formation to yield water depends on two factors - porosity and permeability. Porosity is determined by how much water the soil or rock can hold in the spaces between its particles. Permeability means how interconnected the spaces are so that water can flow freely between them. There are two types of aquifers. One is a confined aquifer, in which a water supply is sandwiched between two impermeable layers. These are sometimes called artesian aquifers because, when a well is drilled into this layer, the pressure may be so great that water will spurt to the surface without being pumped. This is an artesian well. The other type of aquifer is the unconfined aquifer, which has an impermeable layer under it but not above it. -

Water Levels in Major Artesian Aquifers of the New Jersey Coastal Plain, 1988

WATER LEVELS IN MAJOR ARTESIAN AQUIFERS OF THE NEW JERSEY COASTAL PLAIN, 1988 By Robert Rosman, Pierre J. Lacombe, and Donald A. Storck U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4060 Prepared in cooperation with the NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION West Trenton, New Jersey 1995 CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction......................................................... 2 Purpose and scope............................................... 2 Study area...................................................... 2 Previous investigations......................................... 4 Well-numbering system........................................... 4 Methods of data collection...................................... 5 Description of data presented................................... 6 Acknowledgments................................................. 8 Hydrogeology of the Coastal Plain.................................... 8 Description of aquifers and confining units..................... 11 Location of freshwater/saltwater interface...................... 12 Water levels in artesian aquifers of the Coastal Plain............... 13 Cohansey aquifer in Cape May County............................. 13 Water levels............................................... 13 Water-level fluctuations................................... 13 Atlantic City 800-foot sand..................................... 14 Water levels............................................... 14 Water-level -

Flowing Artesian Wells

Flowing Artesian Wells Water Stewardship Information Series Table of Contents What’s the difference between a flowing artesian well Are there specific actions to avoid when flowing artesian and an artesian well? . 1 conditions are present? . 6 Why do wells flow? . 1 How can flowing artesian well be constructed in bedrock aquifers? . 7 Why is stopping or controlling artesian flow important? . 2 How can flowing artesian well be constructed in How can flowing artesian conditions be determined unconsolidated aquifers? . 7 before drilling? . 2 What should be done if flowing artesian conditions are What are the provincial regulatory requirements for suddenly encountered? . 7 controlling or stopping artesian flow? . 2 What are the key factors in completing and equipping What does it mean to “control” artesian flow from a well? . 3 a flowing artesian well? . 8 Will a flowing artesian well dry up if the flow is stopped How is the pressure or static water level for a flowing or controlled? . 3 artesian well measured? . 8 Are there any water quality concerns with flowing How should flowing artesian wells be closed? . 8 artesian wells? . 3 How is a flowing artesian well disinfected? . 9 Are there any other concerns with flowing artesian wells? . 3 Further Information . 9 What can be done with an existing flowing well? . 4 What if the flow is needed, for example, to increase the baseflow of a creek or stream? . 4 Are there some general guidelines for constructing a flowing artesian well? . 4 What are the key issues to be aware of when drilling a flowing artesian well? . 5 This booklet contains general information on flowing artesian wells for well drillers, groundwater consultants and well owners Hydrostatic head (or confining pressure) is the vertical in British Columbia . -

Groundwater Modeling of the Withdrawal

DOI: 10.7343/as-2018-333 Paper Groundwater modeling of the withdrawal sustainability of Cannara artesian aquifer (Umbria, Italy) Modellazione delle acque sotterranee e prelievo sostenibile dall’acquifero artesiano di Cannara (Umbria) Giovanni Pietro Beretta, Monica Avanzini, Tomaso Marangoni, Marino Burini, Giacomo Schirò, Jacopo Terrenghi, Gaetano Vacca Riassunto: L’acquifero di Cannara (Umbria, Italia) è noto da oltre un Abstract: The Cannara aquifer (Umbria, Italy) has been known for more secolo ed è uno dei principali punti di approvvigionamento di acqua than a century, and is one of the main drinking water supplies in the Umbria potabile nella Regione Umbria. All’inizio veniva utilizzato per scopi Region. In the beginning it was used for irrigation purposes, since this area was irrigui, poiché quest’area era prevalentemente agricola fino agli anni mainly agricultural up to the 1960s. The groundwater—exploited by Umbra ‘60. Le acque sotterranee, sfruttate da Umbra Acque S.p.A. (Società che Acque S.p.A. (a Company supplying drinking water)—is 150 m under ground fornisce l’acqua potabile), sono a 150 m al di sotto il livello del suolo e level and is contained in a porous confined aquifer, which originally had arte- sono contenute in un acquifero poroso confinato, che in origine aveva sian characteristics. Exploitation of 200–300 l/s with nine wells caused a re- caratteristiche artesiane. Lo sfruttamento di 200-300 l/s con nove pozzi duction of piezometric level, maintaining the confined aquifer conditions, except ha causato una riduzione del livello piezometrico, mantenendo le con- for a very short period during which the aquifer was depressurised by drought, dizioni di acquifero confinato, ad eccezione di un periodo molto breve and for increase of emergency withdrawals replacing other water supplies (from durante il quale la falda è stata depressurizzata in seguito alla siccità e springs) for drinking purposes. -

The Secret Life of Groundwater

The Secret Life of Groundwater Presented by Natalie Ballew, Texas Water Development Board Activity by Shae Luther and Josh Sendejar, Texas Water Development Board 1 Groundwater flow according to Athanasius Kircher (Kricher, 1665) Image from www.un-igrac.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/Groundwater_around_world.pdf Groundwater has often been perceived as a complete mystery. Imagination and mythology used to drive perceptions of groundwater flow. This is a depiction of groundwater flow from the 1600s. Back then, people believed that water moved from the sea floor up to mountains through mysterious channels where it emerged as springs. The Texas Supreme Court, in more recent history, has even called groundwater ‘secret, occult, and concealed.’ 2 Now, based on scientific observation, we have the water cycle as we know it today. I’m sure y’all are all familiar with the water cycle, how water moves around the earth and atmosphere. The basics, if you need a refresher, evaporation, condensation and precipitation. The water cycle is so much more than just that. Scientists continue to collect data to understand all parts of the water cycle because it’s essential to life on earth and understanding all parts of it can help us make smart decisions around use and conservation to ensure we have water available for generations to come. 3 Today we’ll focus on the groundwater portion of the water cycle. Groundwater is a very important resource in Texas for things like irrigation, public water supply, and environmental needs; in fact, there is more groundwater use in the state than there is surface water use. -

An Overview of Groundwater Management in Texas

11/9/2016 So Secret, Occult, and Concealed: An Overview of Groundwater Management in Texas Robert E. Mace, Ph.D., P.G . Texas Water Development Board presented to The Houston Geological Society November 9, 2016; Houston, Texas data planning financing 1 11/9/2016 The following presentation is based upon professional research and analysis within the scope of the Texas Water Development Board’s statutory responsibilities and priorities but, unless specifically noted, does not necessarily reflect official Board positions or decisions. 2 11/9/2016 Groundwater * This could cost you Pound Cake some dough! ** Add rum for flavor! 1. Are you in a groundwater conservation district, Edwards Aquifer Authority, or subsidence district? 2. If the answer is “No”, then you can do whatever you Want (unless you don’t own the water rights, are in a city that restricts wells, are wasteful, or are mean). 3. If the answer is “yes”, then you need to check with the district and/or authority (and city) to see what you can (or can’t do). 4. Keep close tabs on new laws, rules, and court cases. 3 11/9/2016 Denison, Texas 4 11/9/2016 Railroad East well ? ft well 30 ft 33 ft 5 ft 60 ft 66 ft 20 ft eâÄx Éy VtÑàâÜx 1904 AAAáÉ áxvÜxà? ÉvvâÄà tÇw vÉÇvxtÄxwAAA 5 11/9/2016 Fort Worth: 1876 6 11/9/2016 Dallas • Drilled first well in 1887 • The “Dallas Geyser”: 1,000,000 gallons per day • “Well, I swar: I’d rather go to see that than a hanging!” • Folks proposed drilling 270 wells to turn Big D into a seaport town 7 11/9/2016 Water‐level declines 800 600 400 Paluxy 200 Woodbine -

Wells Introduction/Information Groundwater Is Withdrawn from the Ground Through Wells for Use in Our Homes, Farms, and Industries

Student Handout Student Name___________________ Wells Introduction/Information Groundwater is withdrawn from the ground through wells for use in our homes, farms, and industries. Wells are drilled or driven into water-bearing underground zones called aquifers. A pump is used to withdraw water from the well. A screen is placed at the bottom of the well to keep soil from being pumped out along with the water. When a well is drilled to penetrate any aquifer, water will enter the well casing. In an unconfined aquifer, the water level will stabilize in the well at the top of the saturated zone. The top of the saturated zone is called the water table. In a confined or artesian aquifer, pressure from overlaying soil and water will cause water in the well to rise above the top of the aquifer, potentially resulting in the flow of water above the surface of the ground. A flowing well or artesian well may result. In the model, you can see the artesian well protruding above the lake/stream bed. There is a confining layer of clay above the bottom aquifer of gravel which supplies water to the artesian well. The bottom of the model serves as a confining layer beneath the aquifer. Piezometers are observation wells used by researchers for studying groundwater. They are different from drinking water wells in both their construction and use. Piezometers are smaller and not as durably constructed as drinking water wells because they are meant for observation and testing. Drinking water wells are regulated by state codes that specify the depth required, the materials used, and the locations of the wells. -

Chapter 12 Springs and Wells

Part 650 Engineering Field Handbook National Engineering Handbook Chapter 12 Springs and Wells (210–VI–NEH, Amend. 60, July 2012) Chapter 12 Springs and Wells Part 650 National Engineering Handbook Issued draft July 2012 Cover: The spring flows into Onion Creek in Hayes County, Texas The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all pro- grams.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for commu- nication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal op- portunity provider and employer. (210–VI–NEH, Amend. 60, July 2012) Chapter 12 Springs and Wells Contents 650.1200 Introduction 12–1 650.1201 Source of water supply 12–2 (a) Water-bearing materials ................................................................................12–2 (b) Aquifers in the continental United States ..................................................12–3 -

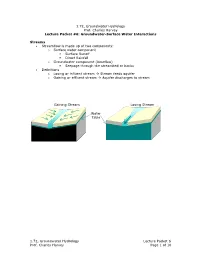

1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Prof. Charles Harvey Lecture Packet #6: Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions

1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Prof. Charles Harvey Lecture Packet #6: Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions Streams • Streamflow is made up of two components: o Surface water component Surface Runoff Direct Rainfall o Groundwater component (baseflow) Seepage through the streambed or banks • Definitions o Losing or influent stream Æ Stream feeds aquifer o Gaining or effluent stream Æ Aquifer discharges to stream Gaining Stream Losing Stream Water Table 1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Lecture Packet 6 Prof. Charles Harvey Page 1 of 10 Stream-Aquifer Interactions Base Flow – Contribution to streamflow from groundwater • Upper reaches provide subsurface contribution to streamflow (flood wave). • Lower reaches provide bank storage which can moderate a flood wave. Flood hydrograph with no bank storage Water leaving bank storage Flood hydrograph with bank storage 0 Stream Discharge 0 Water entering bank storage t0 tP Recharge Recharge Discharge Groundwater inflow and bank storage Groundwater inflow alone Volume Bank Storage Storage Bank 0 Stream Discharge 0 t0 tP t0 tP Springs • A spring (or seep) is an area of natural discharge. • Springs occur where the water table is very near or meets land surface. o Where the water table does not actually reach land surface, capillary forces may still bring water to the surface. • Discharge may be permanent or ephemeral • The amount of discharge is related to height of the water table, which is affected by o Seasonal changes in recharge o Single storm events Types of Springs • Depression spring Land surface dips to intersect the water table • Contact spring Water flows to the surface where a low permeability bed • Fault spring impedes flow • Sinkhole spring Similar to a depression spring, but flow is limited to • Joint spring fracture zones, joints, or dissolution channels • Fracture spring 1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Lecture Packet 6 Prof. -

Background Review: Aquifer Connectivity Within the Great Artesian Basin, and the Surat, Bowen and Galilee Basins

Background review Aquifer connectivity within the Great Artesian Basin, and the Surat, Bowen and Galilee Basins This background review was commissioned by the Department of the Environment on the advice of the Interim Independent Expert Scientific Committee on Coal Seam Gas and Coal Mining. The review was prepared by the CSIRO and revised by the Department of the Environment following peer review. June 2014 Background review: aquifer connectivity within the Great Artesian Basin, and Surat, Bowen and Galilee Basins Copyright © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. Aquifer connectivity within the Great Artesian Basin, and the Surat, Bowen and Galilee Basins, Background review is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ This report should be attributed as ‘Aquifer connectivity within the Great Artesian Basin, and the Surat, Bowen and Galilee Basins, Background review, Commonwealth of Australia 2014’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Department of the Environment, Public Affairs GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Or by email to: [email protected] This publication can be accessed at: www.iesc.environment.gov.au Acknowledgements This background review was commissioned by the Department of the Environment on the advice of the Interim Independent Expert Scientific Committee on Coal Seam Gas and Coal Mining.