Reading Heteromasculinity and Orgasm in Basic Instinct 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Dvds, Music Are Rent-Free at APL by KIMBERLY COON Couldn’T find Anyone to Borrow find Something to Suit Their Way Said

Page 4 ANDERSONIAN / Entertainment April 19, 2006 DVDs, music are rent-free at APL BY KIMBERLY COON couldn’t find anyone to borrow find something to suit their way said. ing free from the library is that ANDERSONIAN STAFF it from. tastes. It’s free for everyone, and cardholders 18 and older can Their solution? The Ander- From TV favorites like AU students need only to bring check out up 10 DVDs and hen sophomore Maggie son Public Library. Friends, Will & Grace, Alias and a copy of their current class 10 videos on their card at one WGrumieaux and junior “The library is a great place even 90210 to recently popular schedule and current photo time. Katie Briski discovered their to get DVDs and videos,” Bris- movies like “Fever Pitch,” “Le- identification to sign up for a For more information, love for the WB’s popular series ki said. She discovered the place gally Blonde” and “Hitch,” the card. check out the library’s web site Gilmore Girls, they couldn’t stop last summer. “They really have a library boasts variety. Check-out times range from at http://www.and.lib.in.us/. watching the show on DVD. lot more than people think.” Classics like “Pretty Wom- seven days for DVDs and vid- “It’s just one of those In addition to books and an” and Marilyn Monroe’s fa- eos to 14 days for new books, shows,” Grumieaux said. “It’s other resources, the library of- mous “Seven Year Itch” are also audiobooks and CDs, but all fun to watch, and I feel like I fers free rental of videos, CDs available, and if you’re willing items can easily be renewed. -

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

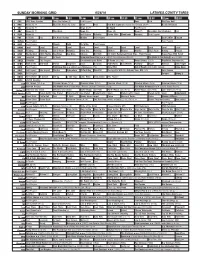

Sunday Morning Grid 6/26/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/26/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Red Bull Signature Series From Detroit. (N) Å Beach Volleyball 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Incredible Dog Challenge Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Earth 2050 FabLab 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Happy Yoga With Sarah 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough ›› (1999) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Un recuerdo para Rubé Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

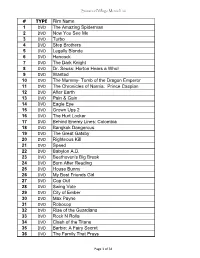

DVD LIST 05-01-14 Xlsx

Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 1 DVD The Amazing Spiderman 2 DVD Now You See Me 3 DVD Turbo 4 DVD Step Brothers 5 DVD Legally Blonde 6 DVD Hancock 7 DVD The Dark Knight 8 DVD Dr. Seuss: Horton Hears a Who! 9 DVD Wanted 10 DVD The Mummy- Tomb of the Dragon Emperor 11 DVD The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 12 DVD After Earth 13 DVD Pain & Gain 14 DVD Eagle Eye 15 DVD Grown Ups 2 16 DVD The Hurt Locker 17 DVD Behind Enemy Lines: Colombia 18 DVD Bangkok Dangerous 19 DVD The Great Gatsby 20 DVD Righteous Kill 21 DVD Speed 22 DVD Babylon A.D. 23 DVD Beethoven's Big Break 24 DVD Burn After Reading 25 DVD House Bunny 26 DVD My Best Friends Girl 27 DVD Cop Out 28 DVD Swing Vote 29 DVD City of Ember 30 DVD Max Payne 31 DVD Robocop 32 DVD Rise of the Guardians 33 DVD Rock N Rolla 34 DVD Clash of the Titans 35 DVD Barbie: A Fairy Secret 36 DVD The Family That Preys Page 1 of 34 Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 37 DVD Open Season 2 38 DVD Lakeview Terrace 39 DVD Fire Proof 40 DVD Space Buddies 41 DVD The Secret Life of Bees 42 DVD Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa 43 DVD Nights in Rodanthe 44 DVD Skyfall 45 DVD Changeling 46 DVD House at the End of the Street 47 DVD Australia 48 DVD Beverly Hills Chihuahua 49 DVD Life of Pi 50 DVD Role Models 51 DVD The Twilight Saga: Twilight 52 DVD Pinocchio 70th Anniversary Edition 53 DVD The Women 54 DVD Quantum of Solace 55 DVD Courageous 56 DVD The Wolfman 57 DVD Hugo 58 DVD Real Steel 59 DVD Change of Plans 60 DVD Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 61 DVD Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters 62 DVD The Cold Light of Day 63 DVD Bride & Prejudice 64 DVD The Dilemma 65 DVD Flight 66 DVD E.T. -

Appendix 1: Selected Films

Appendix 1: Selected Films The very random selection of films in this appendix may appear to be arbitrary, but it is an attempt to suggest, from a varied collection of titles not otherwise fully covered in this volume, that approaches to the treatment of sex in the cinema can represent a broad church indeed. Not all the films listed below are accomplished – and some are frankly maladroit – but they all have areas of interest in the ways in which they utilise some form of erotic expression. Barbarella (1968, directed by Roger Vadim) This French/Italian adaptation of the witty and transgressive science fiction comic strip embraces its own trash ethos with gusto, and creates an eccentric, utterly arti- ficial world for its foolhardy female astronaut, who Jane Fonda plays as basically a female Candide in space. The film is full of off- kilter sexuality, such as the evil Black Queen played by Anita Pallenberg as a predatory lesbian, while the opening scene features a space- suited figure stripping in zero gravity under the credits to reveal a naked Jane Fonda. Her peekaboo outfits in the film are cleverly designed, but belong firmly to the actress’s pre- feminist persona – although it might be argued that Barbarella herself, rather than being the sexual plaything for men one might imagine, in fact uses men to grant herself sexual gratification. The Blood Rose/La Rose Écorchée (aka Ravaged, 1970, directed by Claude Mulot) The delirious The Blood Rose was trumpeted as ‘The First Sex Horror Film Ever Made’. In its uncut European version, Claude Mulot’s film begins very much like an arthouse movie of the kind made by such directors as Alain Resnais: unortho- dox editing and tricks with time and the film’s chronology are used to destabilise the viewer. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

UCSF Tobacco Control Policy Making: United States Title First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67c514kh Authors Polansky, Jonathan R. Glantz, Stanton, PhD Publication Date 2007-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. -

Video-Windows-Grosse

THEATRICAL VIDEO ANNOUNCEMENT TITLE VIDEO RELEASE VIDEO WINDOW GROSS (in millions) DISTRIBUTOR RELEASE ANNOUNCEMENT WINDOW DISNEY Fantasia/2000 1/1/00 8/24/00 7 mo 23 Days 11/14/00 10 mo 13 Days 60.5 Disney Down to You 1/21/00 5/31/00 4 mo 10 Days 7/11/00 5 mo 20 Days 20.3 Disney Gun Shy 2/4/00 4/11/00 2 mo 7 Days 6/20/00 4 mo 16 Days 1.6 Disney Scream 3 2/4/00 5/13/00 3 mo 9 Days 7/4/00 5 mo 89.1 Disney The Tigger Movie 2/11/00 5/31/00 3 mo 20 Days 8/22/00 6 mo 11 Days 45.5 Disney Reindeer Games 2/25/00 6/2/00 3 mo 8 Days 8/8/00 5 mo 14 Days 23.3 Disney Mission to Mars 3/10/00 7/4/00 3 mo 24 Days 9/12/00 6 mo 2 Days 60.8 Disney High Fidelity 3/31/00 7/4/00 3 mo 4 Days 9/19/00 5 mo 19 Days 27.2 Disney East is East 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 9/12/00 4 mo 29 Days 4.1 Disney Keeping the Faith 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 10/17/00 6 mo 3 Days 37 Disney Committed 4/28/00 9/7/00 4 mo 10 Days 10/10/00 5 mo 12 Days 0.04 Disney Hamlet 5/12/00 9/18/00 4 mo 6 Days 11/14/00 6 mo 2 Days 1.5 Disney Dinosaur 5/19/00 10/19/00 5 mo 1/30/01 8 mo 11 Days 137.7 Disney Shanghai Noon 5/26/00 8/12/00 2 mo 17 Days 11/14/00 5 mo 19 Days 56.9 Disney Gone in 60 Seconds 6/9/00 9/18/00 3 mo 9 Days 12/12/00 6 mo 3 Days 101.6 Disney Love’s Labour’s Lost 6/9/00 10/19/00 4 mo 10 Days 12/19/00 6 mo 10 Days 0.2 Disney Boys and Girls 6/16/00 9/18/00 3 mo 2 Days 11/14/00 4 mo 29 Days 21.7 Disney Disney’s The Kid 7/7/00 11/28/00 4 mo 21 Days 1/16/01 6 mo 9 Days 69.6 Disney Scary Movie 7/7/00 9/18/00 2 mo 11 Days 1212/00 5 mo 5 Days 157 Disney Coyote Ugly 8/4/00 11/28/00 3 -

Numbered DVD No

FORTLØPENDE NUMMERERING AV DVD/DVD REGISTRATION BY NUMBERS Sett filmene tilbake i nummerert rekkefølge i hylllen! Please place the DVD's back by numbers! Numbered DVD No. Title Country of origin Category Year 3 The Mummy USA Action / Thriller 1999 6 Drive USA Action 2000 7 Lara Croft - Thomb-Rider USA Action 2000 8 Dykkerne Danish Action 2000 9 Miss Undercover USA Comedy 2000 11 Blow USA Drama 2001 12 Men of Honor USA Action 2001 13 Quills English / French Drama 2001 14 Crimson Rivers French Thriller 2001 15 The Mummy returns USA Action 2001 16 Hannibal USA Thriller 2001 17 The Cell USA Thriller 2000 21 The taylor of Panama USA Thriller 2001 22 Evolution USA SciFi / Comedy 2001 23 The Gift USA Thriller 2001 24 The wedding planner USA Comedy 2000 26 Da jeg traff Jesus med sprettert Norwegian Comedy 2000 27 Dungeons & Dragons USA Fiction 2000 30 Shadow of the Vampire English Horror 2000 33 Papillon USA Action drama 1973 35 Willow USA Fairy-tale 1998 37 Spy game USA Action 2001 38 A Beutiful mind USA Drama 2002 39 Black Hawk down USA War / Drama 2001 40 Behind enemy lines USA War / Action 2001 42 Borettslaget I Norwegian Comedy 2001 43 Borettslaget II Norwegian Comedy 2001 44 The Others USA Thriller 2001 45 The Heist USA Thriller 2001 46 Amalie from Montmarte French Comedy 2002 47 Ocean's Eleven USA Action / Comedy 2001 48 Zoolander USA Comedy 2001 49 Species II USA Thriller 1997 50 Phantoms USA Thriller 1997 51 Midnight in the garden of good and evil USA Thriller 1996 52 Grosse point blank USA Action / Comedy 1998 53 Shallow Hal USA Comedy -

Royal Court Theatre Announces Cast for the End of History…, Written by Jack Thorne and Directed by John Tiffany

PRESS RELEASE TUESDAY 28 MAY 2019 ROYAL COURT THEATRE ANNOUNCES CAST FOR THE END OF HISTORY…, WRITTEN BY JACK THORNE AND DIRECTED BY JOHN TIFFANY. JERWOOD THEATRE DOWNSTAIRS THURSDAY 27 JUNE 2019 – SATURDAY 10 AUGUST 2019 Lead image for the end of history… Lesley Sharp and David Morrissey play husband and wife in Jack Thorne’s new play. Zoe Boyle, Laurie Davidson, David Morrissey, Kate O’Flynn, Lesley Sharp and Sam Swainsbury have been cast in the world premiere of the end of history…, written by Jack Thorne and directed by Royal Court Theatre Associate Director John Tiffany. With design by Grace Smart, lighting by Jack Knowles, sound by Tom Gibbons and movement by Steven Hoggett. the end of history… runs in the Jerwood Theatre Downstairs Thursday 27 June 2019 – Saturday 10 August 2019 with press night on Wednesday 3 July 2019, 7pm. “No talent at all when it comes to cooking - as you will discover - but when it comes to pissing off my children - immense talent - Olympian talent.” Newbury, 1997. Sal is attempting to cook dinner for the family. She and husband David have pulled off a coup and gathered their brood back home for the weekend. Eldest son Carl is bringing his new girlfriend to meet everyone for the first time; middle daughter Polly is back from Cambridge University for the occasion; and youngest Tom will hopefully make it out of detention in time for dinner. Sal and David would rather feed their kids with leftist ideals and welfarism than fancy cuisine. When you've named each of your offspring after your socialist heroes, you've given them a lot to live up to.. -

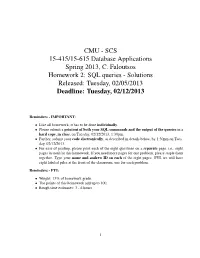

CMU - SCS 15-415/15-615 Database Applications Spring 2013, C

CMU - SCS 15-415/15-615 Database Applications Spring 2013, C. Faloutsos Homework 2: SQL queries - Solutions Released: Tuesday, 02/05/2013 Deadline: Tuesday, 02/12/2013 Reminders - IMPORTANT: • Like all homework, it has to be done individually. • Please submit a printout of both your SQL commands and the output of the queries in a hard copy, in class, on Tuesday, 02/12/2013, 1:30pm. • Further, submit your code electronically, as described in details below, by 1:30pm on Tues- day, 02/12/2013. • For ease of grading, please print each of the eight questions on a separate page, i.e., eight pages in total for this homework. If you need more pages for one problem, please staple them together. Type your name and andrew ID on each of the eight pages. FYI, we will have eight labeled piles at the front of the classroom, one for each problem. Reminders - FYI: • Weight: 15% of homework grade. • The points of this homework add up to 100. • Rough time estimates: 3 - 6 hours. 1 SQL queries on the MovieLens dataset (100 points) [Kate] In this homework we will use the MovieLens dataset released in May 2011. For more details, please refer to: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/˜christos/courses/dbms.S13/hws/HW2/movielens-readme. txt We preprocessed the original dataset and loaded the following two tables to PostgreSQL: movies ( mid, title, year, num ratings, rating) play in (mid, name, cast position) In the table movies, mid is the unique identifier for each movie, title is the movie’s title, and year is the movie’s year-of-release. -

Title Format 1,000 Years of Laughter Audiobook a Bad Birdwatcher's

Title Format 1,000 years of laughter Audiobook A bad birdwatcher's companion Audiobook A guide to wine Audiobook A history of the olympics Audiobook A history of the world in 10? chapters Audiobook A life of dante Audiobook A life of johnson Audiobook A life of shakespeare Audiobook A little princess Audiobook A lover's gift: from her to him Audiobook A lover's gift: from him to her Audiobook A midsummer night's dream Audiobook A portrait of the artist as a young man Audiobook A portrait of the artist as a young man Audiobook A deadly business Audiobook A joe bev audio theater sampler, volume 1 Audiobook A joe bev audio theater sampler, volume 2 Audiobook A long way home Audiobook A sliver of light Audiobook A well‐tempered heart Audiobook Abraham lincoln Audiobook Adolf hitler Audiobook Aesop's fables Audiobook Afghanistan ? in a nutshell Audiobook Agnes grey Audiobook Aida Audiobook Alfred lord tennyson Audiobook Allies of the night Audiobook Always unique Audiobook Ancient greek philosophy ‐ an introduction Audiobook Anna karenina Audiobook Anne of avonlea Audiobook Anne of green gables Audiobook Antonin dvorak Audiobook Aristotle ? an introduction Audiobook Arranged Audiobook Arthur conan doyle, a life Audiobook Atlantis redeemed Audiobook Atlantis unmasked Audiobook Atomic accidents Audiobook Autism breakthrough Audiobook Balthazar Audiobook Bared to the laird Audiobook Barnaby rudge Audiobook Barnaby rudge Audiobook Bedded bliss Audiobook Beowulf Audiobook Beyond good and evil Audiobook Beyond survival Audiobook Bino Audiobook Black