Section 2.1: Set Theory – Symbols, Terminology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lectures on Fractal Geometry and Dynamics

Lectures on fractal geometry and dynamics Michael Hochman∗ March 25, 2012 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Preliminaries 3 3 Dimension 3 3.1 A family of examples: Middle-α Cantor sets . 3 3.2 Minkowski dimension . 4 3.3 Hausdorff dimension . 9 4 Using measures to compute dimension 13 4.1 The mass distribution principle . 13 4.2 Billingsley's lemma . 15 4.3 Frostman's lemma . 18 4.4 Product sets . 22 5 Iterated function systems 24 5.1 The Hausdorff metric . 24 5.2 Iterated function systems . 26 5.3 Self-similar sets . 31 5.4 Self-affine sets . 36 6 Geometry of measures 39 6.1 The Besicovitch covering theorem . 39 6.2 Density and differentiation theorems . 45 6.3 Dimension of a measure at a point . 48 6.4 Upper and lower dimension of measures . 50 ∗Send comments to [email protected] 1 6.5 Hausdorff measures and their densities . 52 1 Introduction Fractal geometry and its sibling, geometric measure theory, are branches of analysis which study the structure of \irregular" sets and measures in metric spaces, primarily d R . The distinction between regular and irregular sets is not a precise one but informally, k regular sets might be understood as smooth sub-manifolds of R , or perhaps Lipschitz graphs, or countable unions of the above; whereas irregular sets include just about 1 everything else, from the middle- 3 Cantor set (still highly structured) to arbitrary d Cantor sets (irregular, but topologically the same) to truly arbitrary subsets of R . d For concreteness, let us compare smooth sub-manifolds and Cantor subsets of R . -

1 Elementary Set Theory

1 Elementary Set Theory Notation: fg enclose a set. f1; 2; 3g = f3; 2; 2; 1; 3g because a set is not defined by order or multiplicity. f0; 2; 4;:::g = fxjx is an even natural numberg because two ways of writing a set are equivalent. ; is the empty set. x 2 A denotes x is an element of A. N = f0; 1; 2;:::g are the natural numbers. Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;:::g are the integers. m Q = f n jm; n 2 Z and n 6= 0g are the rational numbers. R are the real numbers. Axiom 1.1. Axiom of Extensionality Let A; B be sets. If (8x)x 2 A iff x 2 B then A = B. Definition 1.1 (Subset). Let A; B be sets. Then A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B iff (8x) if x 2 A then x 2 B. Theorem 1.1. If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B. Proof. Let x be arbitrary. Because A ⊆ B if x 2 A then x 2 B Because B ⊆ A if x 2 B then x 2 A Hence, x 2 A iff x 2 B, thus A = B. Definition 1.2 (Union). Let A; B be sets. The Union A [ B of A and B is defined by x 2 A [ B if x 2 A or x 2 B. Theorem 1.2. A [ (B [ C) = (A [ B) [ C Proof. Let x be arbitrary. x 2 A [ (B [ C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B [ C iff x 2 A or (x 2 B or x 2 C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B or x 2 C iff (x 2 A or x 2 B) or x 2 C iff x 2 A [ B or x 2 C iff x 2 (A [ B) [ C Definition 1.3 (Intersection). -

Chapter 2 Introduction to Classical Propositional

CHAPTER 2 INTRODUCTION TO CLASSICAL PROPOSITIONAL LOGIC 1 Motivation and History The origins of the classical propositional logic, classical propositional calculus, as it was, and still often is called, go back to antiquity and are due to Stoic school of philosophy (3rd century B.C.), whose most eminent representative was Chryssipus. But the real development of this calculus began only in the mid-19th century and was initiated by the research done by the English math- ematician G. Boole, who is sometimes regarded as the founder of mathematical logic. The classical propositional calculus was ¯rst formulated as a formal ax- iomatic system by the eminent German logician G. Frege in 1879. The assumption underlying the formalization of classical propositional calculus are the following. Logical sentences We deal only with sentences that can always be evaluated as true or false. Such sentences are called logical sentences or proposi- tions. Hence the name propositional logic. A statement: 2 + 2 = 4 is a proposition as we assume that it is a well known and agreed upon truth. A statement: 2 + 2 = 5 is also a proposition (false. A statement:] I am pretty is modeled, if needed as a logical sentence (proposi- tion). We assume that it is false, or true. A statement: 2 + n = 5 is not a proposition; it might be true for some n, for example n=3, false for other n, for example n= 2, and moreover, we don't know what n is. Sentences of this kind are called propositional functions. We model propositional functions within propositional logic by treating propositional functions as propositions. -

Mathematics 144 Set Theory Fall 2012 Version

MATHEMATICS 144 SET THEORY FALL 2012 VERSION Table of Contents I. General considerations.……………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 1. Overview of the course…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 2. Historical background and motivation………………………………………………………….………………4 3. Selected problems………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 I I. Basic concepts. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 1. Topics from logic…………………………………………………………………………………………………………16 2. Notation and first steps………………………………………………………………………………………………26 3. Simple examples…………………………………………………………………………………………………………30 I I I. Constructions in set theory.………………………………………………………………………………..……….34 1. Boolean algebra operations.……………………………………………………………………………………….34 2. Ordered pairs and Cartesian products……………………………………………………………………… ….40 3. Larger constructions………………………………………………………………………………………………..….42 4. A convenient assumption………………………………………………………………………………………… ….45 I V. Relations and functions ……………………………………………………………………………………………….49 1.Binary relations………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ….49 2. Partial and linear orderings……………………………..………………………………………………… ………… 56 3. Functions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ….…….. 61 4. Composite and inverse function.…………………………………………………………………………… …….. 70 5. Constructions involving functions ………………………………………………………………………… ……… 77 6. Order types……………………………………………………………………………………………………… …………… 80 i V. Number systems and set theory …………………………………………………………………………………. 84 1. The Natural Numbers and Integers…………………………………………………………………………….83 2. Finite induction -

The Matroid Theorem We First Review Our Definitions: a Subset System Is A

CMPSCI611: The Matroid Theorem Lecture 5 We first review our definitions: A subset system is a set E together with a set of subsets of E, called I, such that I is closed under inclusion. This means that if X ⊆ Y and Y ∈ I, then X ∈ I. The optimization problem for a subset system (E, I) has as input a positive weight for each element of E. Its output is a set X ∈ I such that X has at least as much total weight as any other set in I. A subset system is a matroid if it satisfies the exchange property: If i and i0 are sets in I and i has fewer elements than i0, then there exists an element e ∈ i0 \ i such that i ∪ {e} ∈ I. 1 The Generic Greedy Algorithm Given any finite subset system (E, I), we find a set in I as follows: • Set X to ∅. • Sort the elements of E by weight, heaviest first. • For each element of E in this order, add it to X iff the result is in I. • Return X. Today we prove: Theorem: For any subset system (E, I), the greedy al- gorithm solves the optimization problem for (E, I) if and only if (E, I) is a matroid. 2 Theorem: For any subset system (E, I), the greedy al- gorithm solves the optimization problem for (E, I) if and only if (E, I) is a matroid. Proof: We will show first that if (E, I) is a matroid, then the greedy algorithm is correct. Assume that (E, I) satisfies the exchange property. -

COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Insights on Computability Turing Machines Are a Model of Computation Two (No Longer) Surpris

Insights on Computability Turing machines are a model of computation COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Lecture 11: Turing Machines Two (no longer) surprising facts: Marius Minea Although simple, can describe everything [email protected] a (real) computer can do. University of Massachusetts Amherst Although computers are powerful, not everything is computable! Plus: “play” / program with Turing machines! 13 February 2019 Why should we formally define computation? Must indeed an algorithm exist? Back to 1900: David Hilbert’s 23 open problems Increasingly a realization that sometimes this may not be the case. Tenth problem: “Occasionally it happens that we seek the solution under insufficient Given a Diophantine equation with any number of un- hypotheses or in an incorrect sense, and for this reason do not succeed. known quantities and with rational integral numerical The problem then arises: to show the impossibility of the solution under coefficients: To devise a process according to which the given hypotheses or in the sense contemplated.” it can be determined in a finite number of operations Hilbert, 1900 whether the equation is solvable in rational integers. This asks, in effect, for an algorithm. Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem (1928): Is there an algorithm that And “to devise” suggests there should be one. decides whether a statement in first-order logic is valid? Church and Turing A Turing machine, informally Church and Turing both showed in 1936 that a solution to the Entscheidungsproblem is impossible for the theory of arithmetic. control To make and prove such a statement, one needs to define computability. In a recent paper Alonzo Church has introduced an idea of “effective calculability”, read/write head which is equivalent to my “computability”, but is very differently defined. -

Section 4.2 Counting

Section 4.2 Counting CS 130 – Discrete Structures Counting: Multiplication Principle • The idea is to find out how many members are present in a finite set • Multiplication Principle: If there are n possible outcomes for a first event and m possible outcomes for a second event, then there are n*m possible outcomes for the sequence of two events. • From the multiplication principle, it follows that for 2 sets A and B, |A x B| = |A|x|B| – A x B consists of all ordered pairs with first component from A and second component from B CS 130 – Discrete Structures 27 Examples • How many four digit number can there be if repetitions of numbers is allowed? • And if repetition of numbers is not allowed? • If a man has 4 suits, 8 shirts and 5 ties, how many outfits can he put together? CS 130 – Discrete Structures 28 Counting: Addition Principle • Addition Principle: If A and B are disjoint events with n and m outcomes, respectively, then the total number of possible outcomes for event “A or B” is n+m • If A and B are disjoint sets, then |A B| = |A| + |B| using the addition principle • Example: A customer wants to purchase a vehicle from a dealer. The dealer has 23 autos and 14 trucks in stock. How many selections does the customer have? CS 130 – Discrete Structures 29 More On Addition Principle • If A and B are disjoint sets, then |A B| = |A| + |B| • Prove that if A and B are finite sets then |A-B| = |A| - |A B| and |A-B| = |A| - |B| if B A (A-B) (A B) = (A B) (A B) = A (B B) = A U = A Also, A-B and A B are disjoint sets, therefore using the addition principle, |A| = | (A-B) (A B) | = |A-B| + |A B| Hence, |A-B| = |A| - |A B| If B A, then A B = B Hence, |A-B| = |A| - |B| CS 130 – Discrete Structures 30 Using Principles Together • How many four-digit numbers begin with a 4 or a 5 • How many three-digit integers (numbers between 100 and 999 inclusive) are even? • Suppose the last four digit of a telephone number must include at least one repeated digit. -

Determinacy in Linear Rational Expectations Models

Journal of Mathematical Economics 40 (2004) 815–830 Determinacy in linear rational expectations models Stéphane Gauthier∗ CREST, Laboratoire de Macroéconomie (Timbre J-360), 15 bd Gabriel Péri, 92245 Malakoff Cedex, France Received 15 February 2002; received in revised form 5 June 2003; accepted 17 July 2003 Available online 21 January 2004 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to assess the relevance of rational expectations solutions to the class of linear univariate models where both the number of leads in expectations and the number of lags in predetermined variables are arbitrary. It recommends to rule out all the solutions that would fail to be locally unique, or equivalently, locally determinate. So far, this determinacy criterion has been applied to particular solutions, in general some steady state or periodic cycle. However solutions to linear models with rational expectations typically do not conform to such simple dynamic patterns but express instead the current state of the economic system as a linear difference equation of lagged states. The innovation of this paper is to apply the determinacy criterion to the sets of coefficients of these linear difference equations. Its main result shows that only one set of such coefficients, or the corresponding solution, is locally determinate. This solution is commonly referred to as the fundamental one in the literature. In particular, in the saddle point configuration, it coincides with the saddle stable (pure forward) equilibrium trajectory. © 2004 Published by Elsevier B.V. JEL classification: C32; E32 Keywords: Rational expectations; Selection; Determinacy; Saddle point property 1. Introduction The rational expectations hypothesis is commonly justified by the fact that individual forecasts are based on the relevant theory of the economic system. -

A Taste of Set Theory for Philosophers

Journal of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research, Vol. XXVII, No. 2. A Special Issue on "Logic and Philosophy Today", 143-163, 2010. Reprinted in "Logic and Philosophy Today" (edited by A. Gupta ans J.v.Benthem), College Publications vol 29, 141-162, 2011. A taste of set theory for philosophers Jouko Va¨an¨ anen¨ ∗ Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Helsinki and Institute for Logic, Language and Computation University of Amsterdam November 17, 2010 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Elementary set theory 2 3 Cardinal and ordinal numbers 3 3.1 Equipollence . 4 3.2 Countable sets . 6 3.3 Ordinals . 7 3.4 Cardinals . 8 4 Axiomatic set theory 9 5 Axiom of Choice 12 6 Independence results 13 7 Some recent work 14 7.1 Descriptive Set Theory . 14 7.2 Non well-founded set theory . 14 7.3 Constructive set theory . 15 8 Historical Remarks and Further Reading 15 ∗Research partially supported by grant 40734 of the Academy of Finland and by the EUROCORES LogICCC LINT programme. I Journal of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research, Vol. XXVII, No. 2. A Special Issue on "Logic and Philosophy Today", 143-163, 2010. Reprinted in "Logic and Philosophy Today" (edited by A. Gupta ans J.v.Benthem), College Publications vol 29, 141-162, 2011. 1 Introduction Originally set theory was a theory of infinity, an attempt to understand infinity in ex- act terms. Later it became a universal language for mathematics and an attempt to give a foundation for all of mathematics, and thereby to all sciences that are based on mathematics. -

180: Counting Techniques

180: Counting Techniques In the following exercise we demonstrate the use of a few fundamental counting principles, namely the addition, multiplication, complementary, and inclusion-exclusion principles. While none of the principles are particular complicated in their own right, it does take some practice to become familiar with them, and recognise when they are applicable. I have attempted to indicate where alternate approaches are possible (and reasonable). Problem: Assume n ≥ 2 and m ≥ 1. Count the number of functions f :[n] ! [m] (i) in total. (ii) such that f(1) = 1 or f(2) = 1. (iii) with minx2[n] f(x) ≤ 5. (iv) such that f(1) ≥ f(2). (v) that are strictly increasing; that is, whenever x < y, f(x) < f(y). (vi) that are one-to-one (injective). (vii) that are onto (surjective). (viii) that are bijections. (ix) such that f(x) + f(y) is even for every x; y 2 [n]. (x) with maxx2[n] f(x) = minx2[n] f(x) + 1. Solution: (i) A function f :[n] ! [m] assigns for every integer 1 ≤ x ≤ n an integer 1 ≤ f(x) ≤ m. For each integer x, we have m options. As we make n such choices (independently), the total number of functions is m × m × : : : m = mn. (ii) (We assume n ≥ 2.) Let A1 be the set of functions with f(1) = 1, and A2 the set of functions with f(2) = 1. Then A1 [ A2 represents those functions with f(1) = 1 or f(2) = 1, which is precisely what we need to count. We have jA1 [ A2j = jA1j + jA2j − jA1 \ A2j. -

PROBLEM SET 1. the AXIOM of FOUNDATION Early on in the Book

PROBLEM SET 1. THE AXIOM OF FOUNDATION Early on in the book (page 6) it is indicated that throughout the formal development ‘set’ is going to mean ‘pure set’, or set whose elements, elements of elements, and so on, are all sets and not items of any other kind such as chairs or tables. This convention applies also to these problems. 1. A set y is called an epsilon-minimal element of a set x if y Î x, but there is no z Î x such that z Î y, or equivalently x Ç y = Ø. The axiom of foundation, also called the axiom of regularity, asserts that any set that has any element at all (any nonempty set) has an epsilon-minimal element. Show that this axiom implies the following: (a) There is no set x such that x Î x. (b) There are no sets x and y such that x Î y and y Î x. (c) There are no sets x and y and z such that x Î y and y Î z and z Î x. 2. In the book the axiom of foundation or regularity is considered only in a late chapter, and until that point no use of it is made of it in proofs. But some results earlier in the book become significantly easier to prove if one does use it. Show, for example, how to use it to give an easy proof of the existence for any sets x and y of a set x* such that x* and y are disjoint (have empty intersection) and there is a bijection (one-to-one onto function) from x to x*, a result called the exchange principle. -

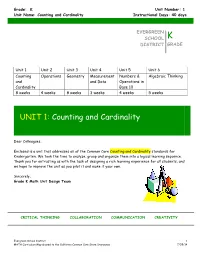

UNIT 1: Counting and Cardinality

Grade: K Unit Number: 1 Unit Name: Counting and Cardinality Instructional Days: 40 days EVERGREEN SCHOOL K DISTRICT GRADE Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Unit 5 Unit 6 Counting Operations Geometry Measurement Numbers & Algebraic Thinking and and Data Operations in Cardinality Base 10 8 weeks 4 weeks 8 weeks 3 weeks 4 weeks 5 weeks UNIT 1: Counting and Cardinality Dear Colleagues, Enclosed is a unit that addresses all of the Common Core Counting and Cardinality standards for Kindergarten. We took the time to analyze, group and organize them into a logical learning sequence. Thank you for entrusting us with the task of designing a rich learning experience for all students, and we hope to improve the unit as you pilot it and make it your own. Sincerely, Grade K Math Unit Design Team CRITICAL THINKING COLLABORATION COMMUNICATION CREATIVITY Evergreen School District 1 MATH Curriculum Map aligned to the California Common Core State Standards 7/29/14 Grade: K Unit Number: 1 Unit Name: Counting and Cardinality Instructional Days: 40 days UNIT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview of the grade K Mathematics Program . 3 Essential Standards . 4 Emphasized Mathematical Practices . 4 Enduring Understandings & Essential Questions . 5 Chapter Overviews . 6 Chapter 1 . 8 Chapter 2 . 9 Chapter 3 . 10 Chapter 4 . 11 End-of-Unit Performance Task . 12 Appendices . 13 Evergreen School District 2 MATH Curriculum Map aligned to the California Common Core State Standards 7/29/14 Grade: K Unit Number: 1 Unit Name: Counting and Cardinality Instructional Days: 40 days Overview of the Grade K Mathematics Program UNIT NAME APPROX.