“Already Made a Name for Myself”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coach's Word Packets©

! ! Coach’s Word Packets © ! 1. Level 1-100 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “A Bus Trip to the River” ! 2. Level 101-200 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “Two Houses” ! 3. Level 201-300 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “A Trip to the Country” ! 4. Level 301-400 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “My School Day” ! 5. Level 401-500 a. Phrases b.Sentences c. Story – “The Good Book” ! ! ©copyright 2014 ! ! ! !2 The New First 100 Fry Words in Phrases ! 1. The people 28. We had their dog 2. of the water 29. By the river water 3. Now and then 30.The first words 4. This is a good day. 31. But not for me 5. From here to there 32. Not him or her 6. up in the air 33. What will they do? 7. Now is the time 34. All or some 8. Can you see? 35. We were 9. That dog is 36. We like to write 10. He has it. 37. When will we 11. He called me. 38. Write your 12. There was 39. Can he 13. for some people 40. She said to go 14. on the bus. 41. So there you are 15. How long are 42. No use 16. as big as the first 43. An angry cat 17. with his mother 44. Each of us 18. for his people 45. Which way 19. What did they say 46. She sat 20. I like him. 47. Do you 21. at your house 48. How did they 22. -

10Th Grade Accelerated English (10X) North Central High School Summer Reading 2021

1 Name: _____________________________________________________________ Date:__________________________ Period: _________ 10th Grade Accelerated English (10X) North Central High School Summer Reading 2021 Assignment: Read and annotate the following texts: ● “Ethnic Hash” By Patricia J. Williams ● “Who Am I This Time?” By Kurt Vonnegut In addition to having read the texts and annotated them, you are exPected to: 1. make claims about characters’ identities 2. find evidence in support of those claims 3. explain how that evidence supports your claims in detail ○ Avoid making a general statement about the quotation as a whole. Focus your explanation on specific parts of the quotation. If typed, responses must be typed in 12-point font and double-spaced. All responses must have a professional, uniform, and neat appearance. The grade earned on the responses will affect your initial grade in the class. Note: Please include an in-text citation, author’s last name and paragraph number, for each quotation. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ “Ethnic Hash” Claim: Williams’ identity is best described as __________________________________________________. Quotation: ExPlanation: 2 “Who Am I This Time?” Claim: Harry’s identity is best described as __________________________________________________. Quotation: ExPlanation: Claim: Helene’s identity is best described as __________________________________________________. Quotation: ExPlanation: 3 “Ethnic Hash” Patricia J. Williams [1] Recently, I was invited to a book party. The book was about pluralism. "Bring an hors d'oeuvre representing your ethnic heritage," said the hostess, innocently enough. Her request threw me into a panic. Do I even have an ethnicity: I wondered. It was like suddenly discovering you might not have a belly button. I tell you, I had to go to the dictionary. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

14 DAYS in JANUARY Photojournalists’ Experiences and Images from Two Historic Weeks in Washington, D.C

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 | A SPECIAL REPORT 14 DAYS IN JANUARY Photojournalists’ experiences and images from two historic weeks in Washington, D.C. After 75 years, this is the final News Photographer in magazine format. Say hell0 to News Photographer digital on nppa.org. See stories on pages 5 and 27. CONTENTS | JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2021 Editor's Column Sue Morrow 5 President's Column Katie Schoolov 27 Advocacy: Legal issues in the wake of the Capitol insurrection Mickey Osterreicher & Alicia Calzada 28 Spotlight: Small-market Carin Dorghalli 36 Pandemic changes the game for sports photographers Peggy Peattie 38 Eyes on Research: Training the next generation to see Dr. Gabriel B. Tate 44 Now we know her story: The woman in the iconic photograph Dai Sugano & Julia Prodis Sulek 48 Irresponsibility could cut off journalists' access to disasters Tracy Barbutes 54 The Image Deconstructed Rich-Joseph Facun, by Ross Taylor 60 14 Days in January Oliver Janney & contributors 70-117 Columnists Doing It Well: Matt Pearl 31 It's a Process: Eric Maierson 32 Career/Life Balance: Autumn Payne 35 Openers/Enders Pages 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 22, 24, 118, 120, 122, 124, 126, 128, 130, 132 ON THE COVER National Guard troops from New York City get a tour through the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol on January 14, 2021. They were part of the defensive security build-up leading up to the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden. Photo by David Burnett ©2020 Contact Press Images U.S. Capitol police try to fend off a pro-Trump mob that breached the Capitol on January 6, 2021, in Washington, D.C. -

Harton Woods

HARTON WOODS My name is Paige Plant, and I’m a singer-songwriter. I have fourteen paintings to prove it—one for each song I’ve written. Thirteen Möbius strip watercolors where I painted the song’s story on the strip. What can I say? I was good at science back in the day. The fourteenth, done in oil and not on a Möbius strip, depicts the only love song I’ve ever written. Not that I’ve had only one lover or anything—I’m quite attractive in a B+ kind of way—but only one worth an oil painting. Plus, oil makes the other guys, and an occasional girl, work a little harder at pleasing me. Everybody wants a love song written about them; almost everyone wants to see their song in oil. Today, I’m going to meet this guy named John Bustin. He’s older, like pensioned, and, well, from the whisper-whisper out there, he was a decent songwriter in his time. No one that most people would know, but he’s well respected in a few east coast music circles. A buddy of mine saw John’s ad online and set us up. I guess John has this million-dollar recording studio in the woods forty miles west of Boston, and he lets singer-songwriters use it for free if he vibes on their stuff. Who knows, maybe I’ll get a few paintings out of the place if things go well. Watercolors. Not oils. I don’t do the daddy thing. Already have one of those, and he’s great. -

Songs for Waiters: a Lyrical Play in Two Acts

SONGS FOR WAITERS: A LYRICAL PLAY IN TWO ACTS Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English By Andrew Eberly Dayton, Ohio May, 2012 SONGS FOR WAITERS: A LYRICAL PLAY IN TWO ACTS Name: Eberly, Andrew M. APPROVED BY: ___________________ Albino Carillo, M.F.A. Faculty Advisor ____________________ John P. McCombe, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ____________________ Andrew Slade, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ii ABSTRACT SONGS FOR WAITERS: A LYRICAL PLAY IN TWO ACTS Name: Eberly, Andrew M. University of Dayton Advisor: Albino Carillo, M.F.A. Through the creative mediums of lyrical poetry, monologues, and traditional dramatic scenes, Songs for Waiters concerns an owner and two employees at an urban bar/restaurant. Through their work, their interactions with the public and each other, and reflecting on their own lives, the three men unpack contemporary debates on work, violence, and sexuality. The use of lyrical poetry introduces the possibility of these portions of the play being put to music in a performance setting, as the play is written to be workshopped and performed live in the future. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………….…………..…iii ACT I…………………………………………………………………………...…………1 ACT II……………………………………………………………………………………35 iv ACT I The play begins with no actors onstage. The set consists of café tables upstage right and left and a bar upstage center. The décor is that of a classic bar with some history. The bar is George’s—known for good food. It’s independent, casual, eclectic, open late, and located on High Street in Columbus, Ohio. -

First 100 Phrases the People Write It Down by the Water Who Will Make It? You and I What Will They Do? He Called Me

First 100 Phrases The people Write it down By the water Who will make it? You and I What will they do? He called me. We had their dog. What did they say? When would you go? No way A number of people One or two How long are they? More than the other Come and get it. How many words? Part of the time This is a good day. Can you see? Sit down. Now and then But not me Go find her Not now Look for some people. I like him. So there you are. Out of the water A long time We were here Have you seen it? Could you go? One more time We like to write. All day long Into the water It’s about time The other people Up in the air She said to go Which way? Each of us He has it. What are these? If we were older There was an old man It’s no use It may fall down. With his mom At your house From my room It’s been a long time. Will you be good? Give them to me. Then we will go. Now is the time An angry cat May I go first? Write your name. This is my cat. That dog is big. Get on the bus. Two of us Did you see it? The first word See the water As big as the first But not for me When will we go? How did they get it? From here to there Number two More people Look up Go down All or some Did you like it? A long way to go When did they go? For some of your people Second 100 Phrases Over the river My new place Another great sound Take a little Give it back. -

CRATERS of the MOON a Thesis Submitted to Kent State University

CRATERS OF THE MOON A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Jack Shelton Boyle May, 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Jack Shelton Boyle B.A., The College of Wooster, 2008 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Chris Barzak________________________, Advisor Dr. Robert Trogdon, Ph.D._____________, Chair, Department of English Dr. James Blank, Ph.D._______________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences iii TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. iii POLAROIDS ................................................................................................................... 1 HANDS SHAPED LIKE GUNS ...................................................................................... 18 SUNFLOWER ............................................................................................................... 22 QUITTING ..................................................................................................................... 24 THE DISAPPEARING MAN .......................................................................................... 41 CHICKENS .................................................................................................................... 42 UNITY ........................................................................................................................... 48 MOON -

1 Column Unindented

DJ PRO OKLAHOMA.COM TITLE ARTIST SONG # Just Give Me A Reason Pink ASK-1307A-08 Work From Home Fifth Harmony ft.Ty Dolla $ign PT Super Hits 28-06 #thatpower Will.i.am & Justin Bieber ASK-1306A-09 (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes MH-1016 (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana ASK-1207-01 1 Thing Amerie & Eve CB30053-02 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's CB30094-04 1,000 Faces Randy Montana CB60459-07 1+1 Beyonce Fall 2011-2012-01 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray CBE9-23-02 100 Proof Kellie Pickler Fall 2011-2012-01 100 Years Five For Fighting CBE6-29-15 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Media Pro 6000-01 11 Cassadee Pope ASK-1403B 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan CBE7-23-03 Len Barry CBE9-11-09 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins CB5134-03-03 18 And Life Skid Row CBE6-26-05 18 Days Saving Abel CB30088-07 1-800-273-8255 Logic Ft. Alessia Cara PT Super Hits 31-10 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Media Pro 6000-01 19 You + Me Dan & Shay ASK-1402B 1901 Phoenix PHM1002-05 1973 James Blunt CB30067-04 1979 Smashing Pumpkins CBE3-24-10 1982 Randy Travis Media Pro 6000-01 1985 Bowling For Soup CB30048-02 1994 Jason Aldean ASK-1303B-07 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Media Pro 6000-01 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block CB30097-07 2 Reasons Trey Songz ftg. T.I. Media Pro 6000-01 2 Stars Camp Rock DISCMPRCK-07 22 Taylor Swift ASK-1212A-01 23 Mike Will Made It Feat. -

Songs by Title

Sound Master Entertainment Songs by Title smedenver.com Title Artist Title Artist #thatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 1994 Jason Aldean (Come On Ride) The Train Quad City DJ's 1999 Prince (Everything I Do) I Do It For Bryan Adams 1st Of Tha Month Bone Thugs-N-Harmony You 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Bryan Adams 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer (Four) 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2 Step Unk & Timbaland Unk (Get Up I Feel Like Being A) James Brown 2.Oh Golf Boys Sex Machine 21 Guns Green Day (God Must Have Spent) A N Sync 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Little More Time On You 22 Taylor Swift N Sync 23 Mike Will Made-It & Miley (Hot St) Country Grammar Nelly Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew 23 (Exp) Mike Will Made-It & Miley (I Wanna Take) Forever Peter Cetera & Crystal Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J Tonight Bernard 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago (I've Had) The Time Of My Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes 3 Britney Spears Life Britney Spears (Oh) Pretty Woman Van Halen 3 A.M. Matchbox Twenty (One) #1 Nelly 3 A.M. Eternal KLF (Rock) Superstar Cypress Hill 3 Way (Exp) Lonely Island & Justin (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake KC & The Sunshine Band Timberlake & Lady Gaga Your Booty 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake (She's) Sexy + 17 Stray Cats & Timbaland (There's Gotta Be) More To Stacie Orrico 4 My People Missy Elliott Life 4 Seasons Of Loneliness Boyz II Men (They Long To Be) Close To Carpenters You 5 O'Clock T-Pain Carpenters 5 1 5 0 Dierks Bentley (This Ain't) No Thinkin Thing Trace Adkins 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train (You Can Still) Rock In Night Ranger 50's 2 Step Disco Break Party Break America 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 6th Avenue Heartache Wallflowers (You Want To) Make A Bon Jovi 7 Prince & The New Power Memory Generation 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 8 Days Of Christmas Destiny's Child Jay-Z & Beyonce 80's Flashback Mix (John Cha Various 1 Thing Amerie Mix)) 1, 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 9 P.M. -

BHM 2008 Spring.Pdf

MAGAZINE COMMITTEE OFFICER IN CHARGE Bill Booher CHAIRMAN Lawrence S Levy VICE CHAIRMEN A Message From the Chairman 1 Tracy L. Ruffeno Gina Steere COPY EDITOR Features Kenneth C. Moursund Jr. EDITORIAL BOARD Katrina’s Gift ................................................. 2 Denise Doyle Samantha Fewox Happy 100th, 4-H .......................................... 4 Katie Lyons Marshall R. Smith III Todd Zucker 2008 RODEOHOUSTONTM ................................. 6 PHOTOGRAPHERS page 2 Debbie Porter The Art of Judging Barbecue .......................... 12 Lisa Van Etta Grand Marshals — Lone Stars ...................... 14 REPORTERS Beverly Acock TM Sonya Aston The RITE Stuff — 10 Years of Success ........ 16 Stephanie Earthman Baird Bill R. Bludworth Rodeo Rookies ............................................... 18 Brandy Divin Teresa Ehrman Show News and Updates Susan D. Emfinger Kate Gunn Charlotte Kocian Corral Club Committees Spotlight ................ 19 Brad Levy Melissa Manning Rodeo Roundup ............................................. 21 Nan McCreary page 4 Crystal Bott McKeon Rochell McNutt Marian Perez Boudousquié Ken Scott Sandra Hollingsworth Smith Kristi Van Aken The Cover Hugo Villarreal RODEOHOUSTON pickup men, Clarissa Webb arguably one of the hardest- HOUSTON LIVESTOCK SHOW working cowboys in the arena, AND RODEO MAGAZINE COORDINATION will saddle up for another year MARKETING & PUBLIC RELATIONS in 2008. DIVISION MANAGING DIRECTOR, page 14 COMMUNICATIONS Clint Saunders Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo™ COORDINATOR, COMMUNICATIONS Kate Bradley DESIGN / LAYOUT CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD: PRESIDENT: CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER: Amy Noorian Paul G. Somerville Skip Wagner Leroy Shafer STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS VICE PRESIDENTS: Francis M. Martin, D.V. M. C.A. “Bubba” Beasley Danny Boatman Bill Booher Brandon Bridwell Dave Clements Rudy Cano Andrew Dow James C. “Jim” Epps Charlene Floyd Rick Greene Joe Bruce Hancock Darrell N. Hartman Dick Hudgins John Morton John A. -

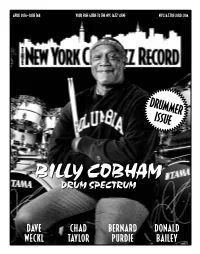

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step.