Anamnesis Not Amnesia the Healing of Memories and the Problem of Uniatism 21St Kelly Lecture, University of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commencement Program

2010 commencement o f St Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary 0 SATURDAY MAY 22, 2010 2 : 0 0 P M St Vladimir’s Seminary 575 Scarsdale Road, Yonkers, NY saturday, may 22, 2010 Commencement Exercises Moleben Processional Opening Prayer: “Troparion for the Three Hierarchs” Opening of the Commencement Exercises His Beatitude, Metropolitan Jonah, President of the Board of Trustees Welcoming Remarks The Very Rev. Dr John Behr, Dean Conferral of Honorary Degrees Commencement Address Mr Albert P. Foundos: “Where My Treasure Is” Conferral of Degrees to the Class of 2010 The Saint Basil the Great Award for Academic Achievement Fr Andrew Cuneo, Christopher Evan McGarvey, Fr Theophan Whitfield Valedictory Address Fr Andrew Cuneo Introduction into the Alumni Association The Very Rev. David Barr, Association President Salutatory Address Michael Soroka Concluding Remarks The Very Rev. Dr Chad Hatfield, Chancellor Closing of the Commencement Exercises His Beatitude, Metropolitan Jonah, President of the Board of Trustees Closing prayer: “It is truly meet” Recessional Commencement Reception on the Lawn Class of 2010 Candidates for the Master of Divinity degree Sdn Justin Ajamian Fr Ephraim Alkhas Fr John Ballard (cum laude) Fr Peter Carmichael “The Meek Shall Inherit the Land” (Psalm 37:11): A Theological Essay on Morality and Land Tenure Economics Fr Benedict Churchill (cum laude) Fr Andrew Cuneo (Valedictorian, summa cum laude) A Commentary on the Rites of the Divine Liturgy by Nicholas Cabasilas: The “Lesser Commentary” Justin Dumoulin Christopher Eid The Antiochian-Syriac Pastoral Agreement of 1991 Fr Simeon B. Johnson Slavophiles and Their Legacy: A Nineteenth Century Movement and Its Continued Impact Fr Sean A. -

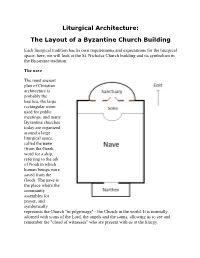

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

THE LITTLE HOURS As Served on Weekdays of the Great Fast and Holy Week ~ 2 ~

THE LITTLE HOURS As served on weekdays of the Great Fast and Holy Week ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ Contents Forward 4 Praying the Psalms 5 Praying the Hours without a Priest 5 First Hour 7 Third Hour 14 Sixth Hour 21 Ninth Hour 29 Appendix A: Texts/Readings from the Triodion 36 Appendix B: Charts for Kathismata 78 Appendix C: Troparia/Kontakia for Sunday/Saturday 81 Appendix D: Troparia/Kontakia of Feasts 86 ~ 4 ~ Forward This book was originally inspired by the daily celebration of the Sixth Hour during the Great Fast at the Chapel of Saints Joachim and Anna at the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute in Ottawa. While the service was celebrated prayerfully and with only a few abbreviations, the need for worshippers to use several books hampered participation in the service. To solve this problem, a book was eventually created containing the text of the Sixth Hour for weekdays of Lent along with an appendix with the propers for each weekday of the Lenten season. This book continues to serve the Institute well. Having left the Institute, I realized that a more comprehensive book of the Little Hours might be useful for clergy and laity who are forced by circumstance to pray the Divine Praises in private, as well as for parishes and chapels where these services are prayed in common. Thus I added the other Little Hours (the First, Third, and Ninth) to the original book, so that a broader selection of the daily office can be prayed. I also added the text of the Old Testament prophecies, so that the lack of a Bible or Prophetologion would not impede the proclamation of scripture. -

THE HOLY ASCENSION ORTHODOX CHURCH Is the Washington, DC

HOLY ASCENSION PARISH NEWSLETTER, JULY-AUGUST 2011 Transfiguration of Our Lord, St Katherine’s Monastery, Sinai. THE HOLY ASCENSION ORTHODOX CHURCH is the Washington, DC, parish of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA), under the omophor (or the conciliar leadership) of Metropolitan Agafangel (Pashkovsky), Bishop of Odessa & Taurida. The Holy Ascension Parish was organized on Ascension Day, 17 May 2007. BISHOPS & LOCAL CLERGY Metropolitan Agafangel, First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, Metropolitan of Eastern America and New York, and Bishop of Odessa & Taurida Bishop Joseph (Hrebinka) of Washington Father John Hinton, priest Deacon Andrew Frick Seraphim Englehardt, subdeacon John Herbst, subdeacon ADDRESS 3921 University Drive, Fairfax VA 22030 703.533.9445. HOLY ASCENSION ORTHODOX CHURCH, JULY 2011 PART 1. OUR PARISH. The Holy Ascension parish welcomes all Orthodox people to its sacraments and all people with an interest in Christianity and the abiding Tradition of the Holy Orthodox Church. The immediate Holy Ascension parish background is Russian émigré and American, with many other English- speaking members. Members, visitors, and people in touch online come from all ethnicities. The Church is One. http://www.holyascension.info/ . http://ruschurchabroad.com/ http://sinod.ruschurchabroad.org/engindex.htm PART 2. NATIVITY OF ST JOHN THE BAPTIST, JULY 7. Christians have long interpreted the life of John the Baptist as a preparation for the coming of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the circumstances of his birth, as recorded in the New Testament, are miraculous. The sole biblical account of birth of St. John the Baptist comes from the Gospel of St Luke. St. -

The Royal Hours of Great and Holy Friday

READER’S PACKET Revised 2014 The Royal Hours of Great and Holy Friday St. Symeon the New Theologian Orthodox Church Birmingham, Alabama The Royal Hours of Great and Holy Friday First Hour (The priest, vested in epitrachelion and phelonion, opens the curtain, and begins:) Priest: Blessed is our God always, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Reader: Amen. Glory to Thee, our God, glory to Thee! O Heavenly King, the Comforter, the Spirit of Truth, Who art everywhere and fillest all things, Treasury of blessings, and Giver of Life, come and abide in us, and cleanse us from every impurity, and save our souls, O Good One. Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us! (3x) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen. O most-holy Trinity, have mercy on us. O Lord, cleanse us from our sins. O Master, pardon our transgressions. O Holy One, visit and heal our infirmities for Thy name’s sake. Lord, have mercy. (3x) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen. Our Father, Who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name. Thy Kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors, and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one. Priest: For Thine is the Kingdom, and the power, and the glory of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. -

Hierarchical Divine Liturgy NOTE: in Most Cases, Only Rubrics That Are Unique to the Bishop’S Presence Are Noted Here

Hierarchical Divine Liturgy NOTE: In most cases, only rubrics that are unique to the Bishop’s presence are noted here. After making three metanias in their respective places, the Priest and the Deacon bow together to the Bishop and then the Deacon says in a loud voice, “Bless, Master!” After the Priest completes, “Blessed is the Kingdom…” the Deacon and the Priest turn and bow together to the Bishop. The bow to the Bishop is repeated after every exclamation by the Priest. The Priest takes his place on the south side of the Holy Table facing north. The Deacon intones the Great Ektenia. At the commemoration of the Hierarchs, the Deacon turns, points his orarion and bows to the Bishop being commemorated while the Priest bows from the Royal Doors., and the choir quickly sings, "Eis polls eti, Despota." At the conclusion of the Ektenia, the Priest moves in front of the Holy Table to intone the exclamation. This process is repeated after each Ektenia. During the singing of the Antiphon, the first Deacon moves from the Icon of Christ back to his place near the Bishop, while the second Priest and second Deacon approach the Bishop, make one metania, ask the Bishop’s blessing and kiss his right hand. The second Priest proceeds through the Royal Doors and the second Deacon proceeds to stand before the Icon of the Theotokos. If there is only one Deacon serving, a Subdeacon may be asked to do this. If there is no Subdeacon, the Deacon remains in his place before the Icon of Christ and from there intones the two Little Ektenias. -

THE HOLY ASCENSION ORTHODOX CHURCH Is the Washington, DC

HOLY ASCENSION PARISH MAY 2009 NEWSLETTER THE HOLY ASCENSION ORTHODOX CHURCH is the Washington, DC, parish of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA), under the omophor (or the conciliar leadership) of Metropolitan Agafangel (Pashkovsky), Bishop of Odessa & Taurida. The Holy Ascension Parish was organized on Ascension Day, May 17, 2007. BISHOPS & LOCAL CLERGY Metropolitan Agafangel, Bishop of Odessa & Taurida, and First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Andronik, Archbishop of Ottawa & North America Bishop Joseph (Hrebinka), Vicar Bishop of Washington Michael Foster, deacon Seraphim Englehardt, subdeacon John Hinton, subdeacon Daniel Olson, reader & choir director ADDRESS 500 West Annandale Road, Falls Church VA 22307 703.539.9445 www.holyascension.info HOLY ASCENSION ORTHODOX CHURCH, MAY 2009 PART 1. OUR PARISH The Holy Ascension parish welcomes all Orthodox people to its sacraments and all people with an interest in Christianity and the abiding Tradition of the Holy Orthodox Church. The immediate Holy Ascension parish background is Russian émigré with many English-speaking converts. Members, visitors, and people in touch online come, however, from all ethnicities. The Church is One. http://ruschurchabroad.com/engindex.htm http://ruschurchabroad.com/ http://www.holyascension.info/ http://www.rocor.us/news.htm PART 2. PASCHAL EPISTLE OF OUR FIRST HIERARCH His Eminence Agafangel, Metropolitan of Eastern America and New York, First Hierarch of the Russian Church Outside of Russia, 2009! CHRIST IS RISEN! 2 RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH ABROAD, DIOCESE OF NORTH AMERICA Right honorable Bishops and Fathers, dear brothers and sisters! Just as the sun lights our sinful world at dawn, so does the Pascha of our Lord illuminate our most sinful souls every year. -

Weekly Bulletin Sunday, September 5, 2021

His Eminence Metropolitan JOSEPH, Archbishop of New York and Metropolitan of all North America His Grace Bishop BASIL Auxiliary Bishop of the Diocese of Wichita and Mid-America RT. Rev. Archimandrite Father Fadi RaBBat Rev. Deacon Miguel ‘Michael’ Sifuentes Pastor Deacon “And the Disciples were First called Christians in Antioch”. Acts 11:26 Tel.: 915-584-9100 www.stgeorge-elpaso.org [email protected] SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2021 Eleventh SundaY aFter Pentecost & Eleventh SundaY oF Matthew Prophet Zachariah, father of the Forerunner Obadiah, bishop of Persia; martyrdom of the Holy Passion-bearer Gleb Tone 2 Eothinon 11 Saturday Vespers Service: 5:00 PM (also available via Live-Streamed) Sunday Service: Orthros (Matins) 9:15 AM, followed immediately by the Divine Liturgy (also available via Live-Streamed) Sunday Epistle Reader: Choir RESURRECTIONAL APOLYTIKION IN TONE TWO When Thou didst submit Thyself unto death, O Thou deathless and immortal One, then Thou didst destroy hell with Thy Godly power. And when Thou didst raise the dead from beneath the earth, all the powers of Heaven did cry aloud unto Thee: O Christ, Thou giver of life, glory to Thee. APOLYTIKION OF THE PROPHET ZACHARIAH IN TONE FOUR In the vesture of a priest, according to the Law of God, thou didst offer unto Him well-pleasing whole- burnt offerings, as it befitted a priest, O wise Zachariah. Thou wast a shining light, a seer of mysteries, bearing in thyself clearly the signs of grace; and in God's temple, O wise Prophet of Christ God, thou wast slain with the sword. -

Monday Bright

Divine Liturgy Variables ononon Bright (Renewal) Monday Transfer of the Commemoration of GreatGreat----martyrmartyr George the TrophyTrophy----BearerBearer NOTE TO CLERGY: Remember to include this special petition in the Great Litany before the one for the head of state, as directed by the Antiochian Archdiocese. Deacon: For Metropolitan Paul, Archbishop John, and for their quick release from captivity and safe return, let us pray to the Lord. Choir: Lord, have mercy. • The Priest begins Divine Liturgy with “Blessed is the Kingdom” and the choir responds “Amen.” Bearing the Paschal Candle, the Priest then leads the singing of the Paschal Apolytikion and censes the Altar as follows: Priest: Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death; and upon those in the tombs bestowing life! Choir: Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death; and upon those in the tombs bestowing life! (TWICE) • Censing the west side of the Altar: Priest: Let God arise, and let His enemies be scattered, and let those that hate Him flee from before His face. Refrain : Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death; and upon those in the tombs, bestowing life! • Censing the south side of the Altar: Priest: As smoke vanisheth, so let them vanish; as wax melteth before the fire. ( Refrain ) • Censing the east side of the Altar: Priest: So let sinners perish at the presence of God, and let the righteous be glad. ( Refrain ) • Censing the north side of the Altar: Priest: This is the day which the Lord hath made; let us rejoice and be glad therein. -

New to a Byzantine Parish? Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin

Responses in Ukrainian Contact Information Some parts of the Divine Liturgy in our parish are said in Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian. The typical responses are: Ukrainian Catholic Church New to a Byzantine Parish? Lord, have mercy. Hospody, Pomilui. ( Господи,помилуй. ) Pastor Rev. Alexander Dumenko Grant this, O Lord. Podai, Hospody. Address 6719 Token Valley Rd. Annunciation of the ( Подай,Господи. ) Manassas, VA 20112 To You, O Lord. Tobi, Hospody. Phone (703) 791-6635 (Church) Blessed Virgin Mary ( Тобi, Господи. ) (301) 421-1739 (Rectory) Ukrainian Catholic Church Manassas, Virginia Seasonal Greeting and Responses Website www.stmarysbyz.com In the Ukrainian Catholic Church, greetings and responses Archeparchy change with the Liturgical Calendar. These can be heard of Philadelphia www.ukrarcheparchy.us being exchanged between parishioners or at the start and end of Father’s homily. Archeparchy Today is the crown of our salvation, and the Newspaper www.ukrarcheparchy.us/the-way/ unfolding of the eternal mystery; the Son of God be- comes the Virgin’s Son, and Gabriel brings the good During most times of the year Please see www.stmarysbyz.com for Liturgy and Confes- “ tidings of grace. With him let us also cry to the Glory to Jesus Christ! Glory Forever! sions times. Slava Isusu Khrystu! Slava Na Viky! Mother of God: Rejoice, Full of grace! The Lord is ( Слава Iсусу Христу! )(Слава на вiки! ) with you. From Easter Sunday (Pascha) to the Feast of the Ascension Troparion for the Feast of The Annunciation Christ is Risen! -

Serving Note for When a Bishop Visits

Serving Rubrics for the Hierarchical Divine Liturgy As served in the Diocese of Philadelphia & Eastern Pennsylvania – Autumn 2015 At Great Vespers: - When the hierarch arrives the bells ring - As the bishop enters the church the curtain and royal doors are opened and he enters the altar. - The antimension is opened with the gospel put aside (like at liturgy) and the bishop venerates it. - You then greet the hierarch and get his blessing. - Close up the antimension and prepare for Great Vespers - A chair is set up on the right (south) side of the front of the church for the hierarch - After you vest the serving clergy exit the altar and receive the hierarch’s blessing before the service begins - Every time there is a censing, you present the censer to the hierarch for his blessing - Every time the hierarch is mentioned in a litany you turn and make a slight bow towards him - Every time you give an explanation you make a slight bow towards the hierarch - At the dismissal you bring out the cross (like at the liturgy) and at the conclusion of the dismissal you present the cross to the hierarch for him to bless the faithful. - Offer some words of greeting to the hierarch on behalf of the parish and then he in turn will say some words of greeting and encouragement to the faithful. - The hierarch will offer the cross - After the veneration the cross the priest offers the final “Through the prayers…” and reenters the altar and closes the doors and curtain. 1 At the Hierarchical Divine Liturgy: BEFORE THE SERVICE: - Orletzi (eagle rugs) are placed: o One at the back door as he comes into the church o Two on the solea. -

RUSSIAN CHURCH SINGING the System of Orthodox Liturgical Singing 23

MMMMMM~ M~,~. The Essence of Liturgical Singing The differences in the structure of Orthodox sevices, as compared to the services of the Roman Catholic Church and, even more so, to those of various Protestant denominations, both determine and reBect divergent viewpoints concerning the significance of the musical element in worship, and hence, concerning the essence, forms and liturgical function of church music. Unless these differences are clearly identified from the start, one risks falling into various misconceptions which would ultimately lead to erroneous conclusions. The first question that must be answered is: What is Orthodox liturgical singing in essence, and what role does it play in Orthodox worship? Such a question may appear, at first glance, to be superfluous; the answer seems to be obvious without any further discussion neces sary: Orthodox liturgical singing is vocal music-music produced by human voices alone-, which, in conjunction with words, accompanies worship services. This answer is understandable if one considers ex clusively the choral singing found in the Russian Orthodox Church during approximately the last three centuries. Thus, one often hears mention, especially in non-Orthodox circles, of "Orthodox church music," to which all of the concepts concerning music in general can be applied. Even present-day Orthodox tend to view their liturgical singing simply as a category of vocal music (and a rather insignificant one even in that capacity), in which one can observe the same musical-aesthetic relationships found in secular music-the only such relationships recognized. As a consequence of this viewpoint, singing at worship is often considered to be a facultative and non-essential element, instead of one that is immanent and inherent in worship.