Participaction: a Legacy in Motion (1971-1999) a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Format Or in HTML at the Following Internet Site

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2006-308 Ottawa, 21 July 2006 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Across Canada Administrative renewals 1. The Commission renews the broadcasting licences for the programming undertakings set out in the appendix to this decision, from 1 September 2007 to 31 August 2008, subject to the terms and conditions in effect under the current licences. 2. This decision does not dispose of any substantive issue that may exist with respect to the renewal of these licences and interested parties will have an opportunity to comment at the appropriate time. Secretary General This decision is to be appended to each licence. It is available in alternative format upon request, and may also be examined in PDF format or in HTML at the following Internet site: http://www.crtc.gc.ca Appendix to Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2006-308 Networks Radio One (English AM service) Radio Two (English FM service) Première Chaîne (French AM service) Espace musique (Chaîne culturelle) French FM service English television service French television service Specialty programming undertakings Newsworld Réseau de l’information (RDI) Transitional digital television undertakings Call sign Associated station Location CBFT-DT CBFT Montréal CBLFT-DT CBLFT Toronto CBLT-DT CBLT Toronto CBMT-DT CBMT Montréal CBOFT-DT CBOFT Ottawa CBOFT-DT-1 CBOFT Toronto CBOT-DT CBOT Ottawa CBUT-DT CBUT Vancouver CBVT-DT CBVT Québec Television programming undertakings CBAFT Moncton, New Brunswick and its transmitters CBAFT-1 Fredericton/Saint John New Brunswick CBAFT-10 Fredericton CBAFT-2 Edmundston CBAFT-3 Neguac CBAFT-4 Grand Falls CBAFT-7 Campbellton CBAFT-8 Saint-Quentin CBAFT-9 Kedgwick ii CBAFT-5 Charlottetown Prince Edward Island CBAFT-6 St. -

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Annual Report For

ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Valuable Canadian Innovative Complete Creative Invigorating Trusted Complete Distinctive Relevant News People Trust Arts Sports Innovative Efficient Canadian Complete Excellence People Creative Inv Sports Efficient Culture Complete Efficien Efficient Creative Relevant Canadian Arts Renewed Excellence Relevant Peopl Canadian Culture Complete Valuable Complete Trusted Arts Excellence Culture CBC/RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 2001-2002 at a Glance CONNECTING CANADIANS DISTINCTIVELY CANADIAN CBC/Radio-Canada reflects Canada to CBC/Radio-Canada informs, enlightens Canadians by bringing diverse regional and entertains Canadians with unique, and cultural perspectives into their daily high-impact programming BY, FOR and lives, in English and French, on Television, ABOUT Canadians. Radio and the Internet. • Almost 90 per cent of prime time This past year, • CBC English Television has been programming on our English and French transformed to enhance distinctiveness Television networks was Canadian. Our CBC/Radio-Canada continued and reinforce regional presence and CBC Newsworld and RDI schedules were reflection. Our audience successes over 95 per cent Canadian. to set the standard for show we have re-connected with • The monumental Canada: A People’s Canadians – almost two-thirds watched broadcasting excellence History / Le Canada : Une histoire CBC English Television each week, populaire enthralled 15 million Canadian delivering 9.4 per cent of prime time in Canada, while innovating viewers, nearly half Canada’s population. and 7.6 per cent share of all-day viewing. and taking risks to deliver • The Last Chapter / Le Dernier chapitre • Through programming renewal, we have reached close to 5 million viewers for its even greater value to reinforced CBC French Television’s role first episode. -

Of Analogue: Access to Cbc/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery

THE END(S) OF ANALOGUE: ACCESS TO CBC/RADIO-CANADA TELEVISION PROGRAMMING IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL DELIVERY by Steven James May Master of Arts, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2008 Bachelor of Applied Arts (Honours), Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1999 Bachelor of Administrative Studies (Honours), Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 1997 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Steven James May, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The End(s) of Analogue: Access to CBC/Radio-Canada Television Programming in an Era of Digital Delivery Steven James May Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University, 2017 This dissertation -

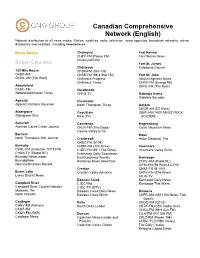

Get Maximum Exposure to the Largest Number of Professionals in The

Canadian Comprehensive Network (English) National distribution to all news media. Dailies, weeklies, radio, television, news agencies, broadcast networks, online databases and websites, including newswire.ca. News Media Chetwynd Fort Nelson CHET-FM [Peace FM] Fort Nelson News Chetwynd Echo British Columbia Fort St. James Chilliwack Caledonia Courier 100 Mile House CFSR-FM (Star FM) CKBX-AM CKSR-FM (98.3 Star FM) Fort St. John CKWL-AM [The Wolf] Chilliwack Progress Alaska Highway News Chilliwack Times CHRX-FM (Energy 98) Abbotsford CKNL-FM (The Bear) CKQC-FM Clearbrook Abbotsford/Mission Times CFEG-TV Gabriola Island Gabriola Sounder Agassiz Clearwater Agassiz Harrison Observer North Thompson Times Golden CKGR-AM [EZ Rock] Aldergrove Coquitlam CKIR-AM [1400 AM EZ ROCK Aldergrove Star Now, The GOLDEN] Ashcroft Courtenay Hagensborg Ashcroft Cache Creek Journal CKLR-FM (The Eagle) Coast Mountain News Comox Valley Echo Barriere Hope North Thompson Star Journal Cranbrook Hope Standard, The CHBZ-FM (B104) Burnaby CHDR-FM (The Drive) Invermere CFML-FM (Evolution 107.9 FM) CJDR-FM (99.1 The Drive) Invermere Valley Echo CHAN-TV (Global BC) Cranbrook Daily Townsman Burnaby NewsLeader East Kootenay Weekly Kamloops BurnabyNow Kootenay News Advertiser CHNL-AM (Radio NL) New Westminster Record CIFM-FM (98 Point 3 CIFM) Creston CKBZ-FM (B-100) Burns Lake Creston Valley Advance CKRV-FM (The River) Lakes District News CFJC-TV Dawson Creek Kamloops Daily News Campbell River CJDC-AM Kamloops This Week Campbell River Courier-Islander CJDC-TV (NTV) Midweek, -

Canadian Claimants Group (CCG)

WRITTEN DIRECT TESTIMONY OF JANICE DE FREITAS (CBC - RIGHTS ADMINISTRATION) 2004—2005 Cable Royalty Distribution Proceeding Docket No. 2007-03 CRB CD 2004-2005 1. Introduction I am Manager of Rights Administration for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation/Radio-Canada (CBC/Radio-Canada) at the Head Office in Ottawa. I have worked for the CBC since 1980. For the last 15 years, I have served as Chairman of the Canadian Claimants Group (CCG). Before assuming my current position, I spent nine years in CBC’s television program distribution department eventually managing the Educational Sales unit. Those responsibilities called for me to be familiar with the English television network’s programming, and rights administration. CBC/Radio-Canada is Canada’s national public broadcaster, and one of its largest and most important cultural institutions. It was created by an Act of Parliament in 1936, beginning with Radio. Bilingual television services were launched in 1952. CBC/Radio-Canada is licensed and regulated by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC)1. CBC/Radio-Canada employs approximately 9,930 Canadians in 27 regional offices across the country. CBC programming is provided on multiple platforms: television (both traditional over-the-air and cable networks), radio, the Internet, satellite radio, digital audio and a recording label. Through this array of activities, CBC/Radio-Canada delivers content in English, French, and eight aboriginal languages. In addition to this, programming is available in seven other languages including Spanish, Russian and Mandarin on both Radio Canada International, and Web-based www.rciviva.ca, a radio service for recent and aspiring immigrants to Canada. -

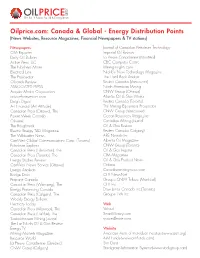

Oilprice.Com: Canada & Global

The No. 1 Source for Oil & Energy News Oilprice.com: Canada & Global - Energy Distribution Points (News Websites, Resource Magazines, Financial Newspapers & TV stations) Newspapers Journal of Canadian Petroleum Technology CIM Reporter Imperial Oil Review Daily Oil Bulletin La Presse Canadienne (Montréal) Active Press, LLC CBC Computer Centre The Northern Miner Mininginsights.com Electrical Line Nickle’s New Technology Magazine The Prospector The Hard Rock Analyst Oilsands Review Reuters Canada (Vancouver) ASSOCIATED PRESS North American Mining Acquire Media Corporation CNW Group (Ottawa) adviceforinvestors.com Atlantic Oil & Gas Works Doig’s Digest Reuters Canada (Toronto) A-T Financial (A-T Attitude) The Mining Equipment Prospector Canadian Press (Ottawa), The CNW Group (Vancouver) Power Week Canada Ocean Resources Magazine Oilweek Canadian Mining Journal The Roughneck Oil & Gas Review Electric Energy T&D Magazine Reuters Canada (Calgary) The Wildcatter News ARE Newsletter CanWest Global Communications Corp. (Toronto) Alberta Oil Magazine Petroleum Explorer CNW Group (Toronto) Canadian Press (Edmonton), The Oil & Gas Inquirer Canadian Press (Toronto), The CIM Magazine Energy Studies Review Oil & Gas Product News CanWest News Service (Ottawa) Octane Energy Analects Canadianminingnews.com Bridge Data CTV NewsNet Propane Canada Groupe CNW Telbec (Montréal) Canadian Press (Winnipeg), The CTV Inc. Energy Processing Canada Dow Jones Canada Inc.(Toronto) Canadian Press (Calgary), The Groupe TVA Inc. Weekly Energy Bulletin Electricity Today -

4Th Session 17Th Legislature

JOURNALS of the LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY of the Province of Saskafchewan From the 29th day of November, 1973, to the 10th day of May, 1974 In the Twenty-second Year of the Reign of Our Sovereign Lady, Queen Elizabeth II, BEING THE FOURTH SESSION OF THE SEVENTEENTH LEGISLATURE OF THE PROVINCE OF SASKATCHEWAN Session, 1973-74 REGINA: R. s. REID, QUEEN'S PRINTER 1974 VOLUME LXXVIII CONTENTS Session, 1973-74 JOURNALS of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan including QUESTIONS AND .ANSWERS Pages 1 to 383 JOURNALS of the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan Pages 1 to 331 QUESTIONS AND .ANSWERS: Appendix Pages 332 to 383 MEETING OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY STEPHEN W OR0BETZ, Lieutenant Governor, (L.S.) CANADA PROVINCE OF SASKATCHEWAN ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her other Realms and Territories, QUEEN, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. To OUR FAITHFUL the MEMBERS elected to serve in the Legislative Assembly of Our Province of Saskatchewan, and to every one of you, GREETING: A PROCLAMATION RoY S. MELDRUM, W HEREAS, it is expedient for causes Att Depu;J' l and considerations to convene the orney enera Legislative Assembly of Our Prov- ince of Saskatchewan, WE Do WILL that you and each of you and all others in this behalf interested on THURSDAY, the TWENTY-NINTH day of NOVEMBER, 1973, at Our City of Regina, personnally he and appear for the despatch of Business, there to take into consideration the state and welfare of Our said Province of Saskatchewan and thereby do as may seem necessary, HEREIN FAIL NoT. -

DTV Post-Transition Allotment Plan

December 2008 Spectrum Management and Telecommunications DTV Post-Transition Allotment Plan Aussi disponible en français Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 DTV Post-Transition Allotment Plan Principles ....................................................................................1 Allotment Criteria......................................................................................................................................1 Coordination with the United States........................................................................................................2 DTV Post-Transition Allotment Plan Description..................................................................................2 Explanatory Notes......................................................................................................................................2 Plan..............................................................................................................................................................4 i DTV Post-Transition Allotment Plan Introduction On November 8, 1997, Canada adopted the ATSC Digital Television standard for terrestrial transmission (Gazette Notice No. SMBR-004-97). In April 1999, the DTV Transition Allotment Plan was published through Gazette Notice No. SMBR-002-99. The plan provided for the introduction and operation of DTV undertakings alongside existing NTSC (National Television -

Canadian Production Companies Past and Present, Including Subsidiaries of U.S

Canadian Production Companies Past and Present, Including Subsidiaries of U.S. and other Foreign-based Companies ©2006-2007 Marsha Ann Tate Last updated: February 20, 2007 @ 9:46 a.m. The following is a list of Canadian film and television production companies compiled from a variety of yearbooks, directories, and other sources published between the 1950s and February 2007. Updates to the list will be made periodically. Comments or suggestions? Please contact: Marsha Ann Tate, 222 Buckhout Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802, Phone: 814-865-7736, Email: [email protected] A AAC Fact (Toronto, Ontario) Fact-based/documentary production arm of Alliance Atlantis Communications AAC Kids (Toronto, Ontario) Children's programming-focused production arm of Alliance Atlantis Communications ABC Films of Canada Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) Able Editing & Service Ltd. (Edmonton, Alberta) Production and distribution company. ABS Productions (Halifax, Nova Scotia) Academy TV Film Productions of Canada (Toronto, Ontario) Producers of industrial and commercial films. Accent Entertainment Corporation (Toronto, Ontario) Company specializes in the production of feature films; movies-of-the-week and series. Adam Productions Ltd. (Vancouver, British Columbia) Adaptel Productions (Montreal, Quebec) Production and distribution company. Orly Adelson Productions (United States) A.C.P.A.V. (Montreal, Quebec) Production and distribution company. ADS Film Productions (Toronto, Ontario) Production and distribution company. Canadian Production Companies Past and Present, rev. February 20, 2007, Marsha Ann Tate 2 Advertel Productions Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) Manager: O. Collier Agincourt Productions Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) Agravoice Productions Ltd. (Edmonton, Alberta) A.K.A. Cartoon (Vancouver, British Columbia) AKO Productions Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) President: A. Kenneth Orton Secretary: Ian R. -

Testimony of Lucy Medeiros

TESTIMONY OF ALISON SMITH (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Introduction My name is Alison Smith. I am currently a Washington Television News Correspondent for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. I have worked for CBC News for more than 30 years in a variety of positions, but primarily as a news anchor and reporter. I am now based in Washington DC covering US news of interest to Canadians. That includes US politics, foreign affairs, the economy and news features that reflect American life. The CBC The CBC’s mandate is to provide programming that is predominantly and distinctively Canadian and to actively contribute to the flow and exchange of cultural expression. CBC News The CBC News Service was established almost 70 years ago in 1941. As an important component of CBC, the mandate for CBC News mirrors that of the corporation. With its team of experienced and highly professional journalists it is seen as one of the greatest strengths of the CBC. It is Canada’s largest news service with more than 800 journalists employed at home and around the world. It currently has more bureaus across Canada than any other network and 14 outside of the country. There are three bureaus in the US – Washington, New York and Los Angeles. Other locations include London, Paris, Jerusalem, Mexico City, Moscow, Beijing, Shanghai, Nairobi, Bangkok and Kandahar. From the inception of the news service, CBC news and current affairs journalists have won international recognition for their work. A list of international awards covering the time period at issue here is attached to this testimony (Exhibit CDN-2-A). -

Of Television, 1954-1969

WE PROUDLY BEGIN OUR BROADCAST DAY: SASKATCHEWAN AND THE ARRIVAL OF TELEVISION, 1954-1969. A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Bonnie Christine Wagner ©Copyright Bonnie Christine Wagner, October 2004. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Masters of Arts Degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N SAS ABSTRACT Television was one of the most pervasive and influential media of the twentieth century. -

Broadcaster NOVEMBER 1973 - Fall '73

Broadcaster NOVEMBER 1973 - fall '73 s1910 NO NO1S3N 1$ NHO1' VZ I 0S6-62-SLHeriLnde directory $7.50 WARD BECK Dependable people with a reputation for design excellence in close collaboration with our clients O .4. ®*. O se 6+B 0!. .®. 0 ìs+ it,i® 444. e 01. .ás< n ) â é i4 siwá. 611J 0w -. 1-4"1...... 4 4 ai., ®Ile.: *. AUDIO CONSOLE AND DISTRIBUTION FACILITIES DESIGNED FOR AMERICAN BROADCASTING COMPANY, CHICAGO WARD -BECK . A SYSTEMS ENGINEERING AND MANUFACTURING ORGANIZATION OPERATING FROM MODERN WELL- PLANNED PREMISES IN TORONTO. WARD-BECK IS AN ESTABLISHED SUPPLIER OF AUDIO CONTROL CONSOLES, DISTRIBUTION AMPLIFIERS, INTERCOM SYSTEMS, SOLID STATE SWITCHING SYSTEMS AND RELATED AUDIO COMPONENTS. OUR EXPERTISE IN THE DESIGN AND MANUFACTURE OF CUSTOM AUDIO EQUIPMENT QUALIFIES US TO FURNISH FACILITIES OF UNCOMPROMISING STANDARDS TO YOUR EXACT SPECIFICATIONS. WE WARD - BECK SYSTEMS LTD. B 841 Progress Avenue, Scarborough, Ontario M1H 2X4 Telephone: (416) 438 -6550. Telex: 06 -23469 EDITORIAL A FULL ROLE FOR FM The public hearings of the Canadian Radio -Television Commission on its Proposal for an FM Policy in the Private Sector produced few surprises. As already reported in Broadcaster in September, the Canadian Association of Broad- casters' brief endorsed the CRTC proposal in principle - describing it as "realistic, constructive and right" - but voiced reservations about some specifics. For his part, Pierre Juneau allayed fears that rigid programming standards would be imposed without consideration of each station's circumstances. It is not the intention of the commission, he said, "to establish a pattern which all stations must follow ". There is really no reason to doubt the CRTC on this point, but it is difficult to quiet all fears when it is common knowledge that few FM stations are in the black now - and more in -depth programming for even more select audiences is going to be expensive.