October 28, 2020 Western Edition Volume 2, Number 41

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8-23-21 Florida Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried Shares Facts to Encourage People to Work Together

HardisonInk.com Florida Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried shares facts to encourage people to work together to reduce the spread of COVID-19 Information Provided By FDACS Communications Published Aug. 23, 2021 at 4:11 p.m. PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Following is the written version of a message Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Nikki Fried shared today (Monday, Aug. 19) during a press briefing in Tallahassee. She urges people to work together to fight against COVID-19. Following is what she said. TALLAHASSEE -- Hi, I’m Nikki Fried, Florida’s Commissioner of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Four weeks ago, as our state began witnessing record-high cases, hospitalizations and deaths, I stood up at the Florida Capitol to provide the public with the latest COVID-19 information – something the governor and the Florida Department of Health ceased providing the first week of June. I made a promise that day to continue providing the regular, timely updates that the people of Florida need and deserve to be able to make the best decisions to keep their families safe during this public health crisis. And I have kept that promise, holding near-daily briefings for the past four weeks. I’m here again today because the governor and Florida Department of Health have failed to provide daily COVID-19 updates for nearly three months even as the situation in the state has continued to worsen. Since my first briefing four weeks ago, hospitalizations in the state have nearly doubled – causing staff shortages and pushing our hospitals to capacity. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, there are currently 17,143 Floridians lying in hospital beds with COVID-19 as we speak – including 3,557 COVID patients in the ICU. -

Guide to Services 2021

GUIDEGUIDE TOTO SERVICESSERVICES 20212021 December 2020 Martin County Indiantown Rd Zone A: Evacuate if you live in a A 1 manufactured home/mobile home; A have substandard construction; or live in a flood-prone area. 1 B Donald Ross R y e d e a L A i w n 1 e h A H g t i w rl y l T H A y P S GA Blvd r a U t i l Mi Northlake Blvd d C N o R n n e y r e s y n H Orange Blvd a w t i w y h d d v W l a t 45th B o t N St r a B B r S P P R l a 7 e y l £98 o ¤ State Road 80 o Ext n R i m Okeechobee Blvd y e w S Gator Blvd H e «¬80 i ¤£441 South ern Blvd x County Road 880 i D ¤£1 d v Forest Hill Blvd l B n Be inspired by 10th Ave N a e Lake Worth Rd c O C S o n d B n Lantana Rd r e R o rs Nature’s magic Lake wOkeechobee g H n w o The Department of Environmental Resources Management invites s F y J a S you to explore the beauty and wonder of Palm Beach County’s natural r ¤£441 Blvd m Gatewa y R treasures. Whatever the activity - hiking, fishing, diving, trail running, d 98 7 ¤£ d d d Boynton Beach Blv paddling, bird watching, bicycling or horseback riding - we’ve got the v l a l B o perfect outdoor destination for you. -

Ag Groups Playing No Favorites in Secretary Sweepstakes

December 2, 2020 Volume 16, Number 46 Ag groups playing no favorites in secretary sweepstakes Farm groups are pledging to work with whomever President-elect Joe Biden picks for agriculture secretary and are steering clear of announcing a favorite for the position. That’s not the case with several other interest groups. So far, most of the public speculation has centered on a pair of longtime Capitol Hill farm hands: Former North Dakota Sen. Heidi Heitkamp and Ohio Rep. Marcia Fudge. Debate over the two has turned into a proxy battle for the direction of the Department of Agriculture under the Biden administration. And farm policy insiders haven’t been able to squeeze much out of the Biden transition team. “They do a lot of listening; they don’t do much Rep. Marcia Fudge (left) and former Sen. Heidi sharing about what they are looking for,” one source Heitkamp (right) told Agri-Pulse of his conversations with the transition team. “As you would expect with any transition team, they hold their cards very, very close.” In recent weeks, ag lobbyists told Agri-Pulse of their generally good relationships with both Heitkamp and Fudge and said they were also generally happy with some of the other people said to be in the running – former Obama administration veterans like USDA Deputy Secretaries Kathleen Merrigan and Krysta Harden and Michael Scuse, who served as deputy in an acting role, former Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack's Chief of Staff and current California Ag Secretary Karen Ross, even Vilsack himself – and none went as far as to endorse a favorite. -

Medical Marijuana Advisory Board Summit Program

MEDICAL MARIJUANA ADVISORY BOARD SPEAKERS NICOLE “NIKKI” FRIED The Broward County Medical Marijuana Advisory Board (MMAB) was created by COMMISSIONER OF AGRICULTURE & CONSUMER SERVICES, STATE OF FLORIDA Broward County Ordinance 2017-29 and enacted on September 14, 2017. The purpose of the MMAB is to: Nicole “Nikki” Fried, Florida’s 12th Commissioner of Agriculture and Consumer Services, is a lifelong Floridian, attorney, and • Advise and make recommendations to the Board of County Commissioners for passionate activist. Born and raised in Miami, Commissioner Fried improving operations and services for growing, processing, and selling medical graduated from the University of Florida, where she received her marijuana for qualified patients and users; bachelor’s, master’s and juris doctorate degrees. While in law • Obtain information concerning medical marijuana and related matters within school, she served as student body president, the first woman to Broward County; hold the position in nearly two decades. Before her election, Fried worked as an advocate in • Provide recommendations to the Board of County Commissioners regarding Tallahassee, representing at-riskTallahassee, children and the Broward County School Board, and working to regulations and fees related to medical marijuana treatment centers; and expand patient access to medical marijuana. Fried has served in the Alachua County Public • Develop programs to educate the citizens of Broward County as to the benefits Defender’s Office as head of the Felony Division, and worked with law firms as a government consultant, advocating on behalf of clients before the Florida Legislature. Working in private and disadvantages of the use of medical marijuana. practice in South Florida, she defended homeowners against foreclosure during the 2007-2008 housing crisis. -

Cortevapac Q4 2019

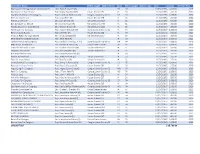

Committee Name Candidate Office Sought - District Name State Office Sought - District Type Date Amount Election Year Ryan Quarles for Agriculture Commissioner Hon. Ryan F. Quarles (R) KY CB 10/15/2019 $ 2,000.00 2019 Kaufmann for State House Rep. Bobby Kaufmann (R) House District 073 IA SH 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Lisa Blunt Rochester For Congress Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester (D) Congressional District 01 DE FH 11/5/2019 $ 2,500.00 2020 Klein for Statehouse Rep. Jarad Klein (R) House District 078 IA SH 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Friends of Whitver Sen. Jack Whitver (R) Senate District 019 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 500.00 2020 Dan Zumbach for Senate Sen. Dan Zumbach (R) Senate District 048 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Waylon Brown for State Senate Sen. Waylon Brown (R) Senate District 026 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Finkenauer For Congress Rep. Abby Finkenauer (D) Congressional District 01 IA FH 11/5/2019 $ 2,500.00 2020 Hein for State House Rep. Lee Hein (R) House District 096 IA SH 11/5/2019 $ 500.00 2020 Amanda Ragan for Iowa Senate Sen. Amanda Ragan (D) Senate District 027 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2022 Mike Naig for Iowa Agriculture Hon. Mike Naig (R) IA CB 11/5/2019 $ 1,000.00 2022 Sanford Bishop For Congress Rep. Sanford D. Bishop, Jr. (D) Congressional District 02 GA FH 11/5/2019 $ 1,000.00 2020 Mike Braun For Indiana Sen. Michael K. Braun (R) United States Senate IN FS 11/5/2019 $ 1,000.00 2024 Schneider for State Senate Sen. -

News R Elease

Contact: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sarah Grace Edison April 9, 2019 Manager, Communications (202) 296-9680 [email protected] State Ag Officials Pledge to Reduce Food Loss, Waste Year-Round During “Winning on Reducing Food Waste Month” WASHINGTON, D.C.—The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA) pledged today to work with federal partners to build on new and existing efforts to reduce food loss and food waste in the United States. NASDA President and New Mexico Secretary of Agriculture Jeff Witte, Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Nikki Fried and NASDA CEO Dr. Barbara P. Glenn participated in the event organized by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) to recognize April as “Winning on Reducing Food Waste Month” and discuss the impacts of reducing food loss and waste. “We are identifying opportunities to mitigate food waste with our federal and industry partners,” Witte said. “It is estimated that 30-40 percent of food is lost throughout the supply chain, including unharvested crops. Regaining lost food is a must to sustainably provide for everyone.” Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture Ryan Quarles also signed the pledge. Connect with NASDA at nasda.org/news or on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to learn more about how state departments of agriculture are reducing food waste. NEWS RELEASE NASDA represents the elected and appointed commissioners, secretaries, and directors of the departments of agriculture in all fifty states and four U.S. territories. NASDA grows and enhances agriculture by forging partnerships and creating consensus to achieve sound policy outcomes between state departments of agriculture, the federal government and stakeholders. -

Biden Cabinet Candidates and Senior White House Positions 4835-4287-3297 V.4.Xlsx

Nominated/Appointed Favored Department Name Description Rep. Cheri Bustos Congresswoman from Illinois; former member of East Moline, Ill. City Council Rep. Marcia Fudge Congresswoman from Ohio; former mayor of Warrensville Heights, Ohio Krysta Harden Former Deputy Agriculture Secretary Senior Fellow in International and Public Affairs at Brown University’s Watson Institute; former senator from North Dakota; former North Dakota attorney Heidi Heitkamp general Amy Klobuchar Minnesota senator; former prosecutor in Minneapolis and candidate for the Democratic nomination AGRICULTURE Kathleen Merrigan Former deputy Agriculture Secretary Collin Peterson Representative from Minnesota and House Agriculture Committee Chairman Chellie Pingree Representative from Maine Karen Ross Former Chief of Staff to Obama Secretary of Agriculture Michael Scuse Delaware Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack Former Iowa governor who served as agriculture secretary for Mr. Obama Xavier Becerra California attorney general; former California congressman and state Assembly member Preet Bharara Former US Attorney for the Southern District of NY Merrick Garland Federal appeals court judge Jeh Johnson Former Obama Homeland Security Secretary ATTORNEY GENERAL/ Doug Jones Alabama senator; former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama JUSTICE Lisa Monaco Former chief counterterrorism and homeland security advisor to Obama Deval Patrick Former Massachusetts Governor Tom Perez Chair of the Democratic National Committee; former secretary of Labor; former assistant attorney general for civil rights Sally Yates Partner, King and Spalding; former acting attorney general and deputy attorney general; former U.S. attorney in the Northern District of Georgia CIA David Cohen Former Deputy CIA Director CLIMATE ENVOY John Kerry Former Secretary of State Jared Bernstein Biden Economic Advisor Heather Boushey Economist Rep. -

Requirements to Register to Vote

NONPARTISAN SCHOOL BOARD REQUIREMENTS CLAY COUNTY (4– Year Terms) Telephone: (904) 336-6500 TO REGISTER TO VOTE District 1 - Janice Kerekes - * 2022 County Court Judges Telephone: (904) 571-9618 • You may register if you are: A U.S. citizen (6– Year Terms) and legal resident of the state of Florida; Timothy R. Collins - Next Election 2022 District 2 - Carol Studdard - * 2020 eighteen years of age (you may pre-register at Telephone: (904) 284-6327 Telephone: (904) 264-9649 16 years of age). Kristina K. Mobley - Next Election 2024 District 3 - Tina Bullock - * 2022 Telephone: (904) 529-4730 Telephone: (904) 510-0516 • When to register: You may register up to 29 District 4 - Mary Bolla - * 2020 days before an election. Registration books Telephone: (904) 276-4860 will then be closed until after the election. CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS District 5 - Ashley Gilhousen - * 2022 You must be registered 29 days prior to the Know Your (4– Year Terms) Next Election 2020 Telephone: (904) 679-9169 election that you wish to vote in. Located in Green Cove Springs, FL 32043 * Next Election Elected Officials • Where to register: The Elections Office, pub- Clerk of the Court - Tara S. Green (R) lic libraries, driver’s license offices and public COUNTY COMMISSIONERS P.O. Box 698 assistance offices or ClayElections.gov. (4– Year Terms) Telephone: (904) 284-6302 P.O. Box 1366 • How to change your address or name: You www.ClayClerk.com Telephone: (904) 269-6376 can call our office to change your address Property Appraiser - Roger A. Suggs (R) ClayCountyGov.com within the state of Florida. -

Athletic Year in Review 2019–2020 Gator Boosters, Inc

ATHLETIC YEAR IN REVIEW 2019–2020 GATOR BOOSTERS, INC. | UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019-2020 YEAR IN REVIEW THE MISSION OF GATOR BOOSTERS, INC. IS TO STRENGTHEN THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA’S ATHLETIC PROGRAM BY ENCOURAGING PRIVATE GIVING AND VOLUNTEER LEADERSHIP FROM GATORS EVERYWHERE. 2019–2020 | SPORTS RESULTS | University Athletic Association, Inc. P.O. Box 14485 Gainesville, FL 32604 Gator Boosters, Inc. P.O. Box 13796 Gainesville, FL 32604 1-800-344-2867 | (352) 275-4683 1 INSPIRED & MOTIVATED DEAR GATOR BOOSTERS, 2019-20 SEASON HIGHLIGHTS Our mission—to strengthen the University of Florida’s athletic program by encouraging private > 12 Gator teams finished 2019-20 action giving and volunteer leadership from Gators ranked in the top 12—including 10 in everywhere—took on new meaning in an unusual the top 10 year for our Gators in competition and for fans > 62 Gators claimed a total of 123 everywhere. Though many of our student- athletes received the news their competition All-America honors. Not all sports schedules would be cut short or canceled named 2020 All-Americans altogether due to ramifications from COVID-19, > Florida claimed three Southeastern they remained committed to academic growth Conference titles—gymnastics, men’s as a record-high 3.19 overall grade point average swimming & diving and volleyball. Nine was earned by Gator student-athletes in 2019-20. Gator teams did not complete (or in The contributions you make provides the some cases, begin) 2020 league action. opportunity for more than 500 student-athletes on 21 men’s and women’s teams to pursue their > Two Gators picked up SEC Athlete of education at a Top 10 Public University. -

For a Complete Directory Please Click Here

PLYMOUTH COUNTY Plymouth County, the fourth largest county in the state of Iowa, was established on January 15, 1851 and formally organized on October 12, 1858. It is named after the landing place of the Pilgrims on the Mayflower. The county was attached to Woodbury County for judicial and other reasons prior to 1858. Plymouth County began with two civil townships. The county now has 24 townships. The site of the first courthouse was in Melbourne. It was built in October of 1859 at a cost of $2,000. In 1861 the building was insured, desks were purchased and an outhouse and steps were added. The courthouse in Melbourne had many uses, including winter quarters for soldiers for the federal government, as well as a grocery. The first public school was taught in Melbourne in December 1859. Records show that the school fund was $470 and the number of students registered was 32. In 1872, by a close vote, the county seat was moved to Le Mars. The town of Le Mars had been platted in 1869, and was named by using the initials of the names of ladies who visited the town with a group of realtors, a state legislator and a state registrar of deeds. In 1874, residents voted to build a new courthouse and jail in Le Mars on Block 35. Three thousand dollars was approved by the voters and appropriated from the swamp land fund of Sioux City and the Iowa Falls Town Lot and Land Company donated the land. In 1900, at the general election on November 6, a bond issue was passed to build a new courthouse, at a cost of no more than $70,000. -

2020 Woodbury County Elected Officials Directory

2020 WOODBURY COUNTY ELECTED OFFICIALS DIRECTORY Prepared by Office of PATRICK F. GILL AUDITOR & RECORDER & COMMISSIONER OF ELECTIONS 2020 Elected Officials Directory Revised 9/14/2020 2020 FEDERAL, STATE & COUNTY OFFICES (4 Yr Term) U.S. President Donald J. Trump 1-1-17 thru 12-31-20 U.S. Vice President Michael R. Pence 1-1-17 thru 12-31-20 U.S. SENATORS (6 Yr Term) Chuck E. Grassley (R) 1-1-17 thru 12-31-22 Joni Ernst (R) 1-1-15 thru 12-31-20 U.S. REPRESENTATIVES (2 Yr Term) 4th Congressional District Steve King (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-20 IOWA STATE OFFICES (4 Yr Term) Governor Kim Reynolds (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 Lieutenant Governor Adam Gregg (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 Secretary of State Paul D. Pate (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 Auditor of State Rob Sand (D) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 Attorney General Tom Miller (D) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 Treasurer of State Michael L. Fitzgerald (D) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 IOWA STATE SENATORS (4 Yr Term) 3rd Senatorial District Jim Carlin (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 7th Senatorial District Jackie Smith (D) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 9th Senatorial District Jason Schultz (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-22 IOWA STATE REPRESENTATIVES (2 Yr Term) 5th Representative District Thomas Jeneary (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-20 6th Representative District Jacob Bossman (R) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-20 13th Representative District Chris Hall (D) 1-1-19 thru 12-31-20 14th Representative District Timothy H. -

Joint Session Tackles Housing Affordability

The Daily Iowan WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2020 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ INSIDE Trial date of man accused Faculty plan for catastrophic-leave policy of killing JoEllen Browning to be moved The dates for the trial and case Faculty Senate discussed a second phase of updates to the catastrophic-leave program, which aims to management conference of Roy Browning — the create a central donation pool and to organize the ways in which leave is donated and received. man accused of killing his wife, BY RACHEL SCHILKE University of Iowa Faculty and and improve how do- He said the second phase will in- UI Health Care [email protected] budget official Staff Disability Services Director nations are received. clude a total review of the program, JoEllen Browning Nathan Stucky provided an update “We want to create exploring how donations are request- — will be reset to The University of Iowa Faculty on the next step in the catastroph- a centralized pool of ed and where they come from. One of different dates. Senate on Tuesday planned for the ic-leave policy at the shared-gover- sorts that anyone in the review methods included updat- Roy Browning The case second phase of the catastroph- nance branch’s Tuesday meeting in the catastrophic-leave ing the website so that it presents the management ic-leave policy, discussing how va- the Old Capitol Senate Chambers. program can pull out program’s stance on confidentiality conference was set for Friday, and cation-leave time is donated and re- Sick leave cannot currently be Stucky of,” Stucky said.