Tendinitis and Bursitis Tendinitis and Bursitis Are Common Complaints, and Are Primarily Due to Overuse Or Repetitive Microtrauma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennis Elbow Handout 503-293-0161

® ® sports INjury medicine department 9250 SW Hall Blvd., Tigard, OR 97223 Tennis Elbow Handout 503-293-0161 WHAT IS IT? Lateral Epicondylitis Tennis elbow, also known as lateral epicondylitis, is one of the most common painful conditions of the elbow. Inflammation and (Tennis Elbow) pain occur on and around the outer bony bump of the elbow where the muscles and tendons attach to the bone. These structures are responsible for lifting your wrist up so this condition can occur with many activities, not just tennis. Humerus (arm bone) Area of pain Tendon lateral epicondyle WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS? Most commonly you will have pain & tenderness on the outer side of the elbow and this pain may even travel down the forearm. Often there is pain and/or weakness with gripping and lifting activities. You may also experience difficulty with twisting activities during sports or even opening the lid of a jar. WHY DOES IT HURT? It hurts because you are putting tension on a place where the tissue is weakened, which is usually due to a degenerative process that seems to take a long time for your body to recognize and heal. WHY DO I HAVE IT? This is a common problem and unfortunately we don’t know why some people get this condition and others do not. Surprisingly, it is not at all clear that it comes from overuse or something that you did “wrong”. There is no doubt that if you do have tennis elbow, it will bother you more to do certain things, but that does not necessarily mean it was caused by those activities. -

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) for Plantar Fasciitis Page 1 of 19 and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) for Plantar Fasciitis Page 1 of 19 and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions Medical Policy An Independent Licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. Title: Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions Professional Institutional Original Effective Date: July 11, 2001 Original Effective Date: July 1, 2005 Revision Date(s): November 5, 2001; Revision Date(s): December 15, 2005; June 14, 2002; June 13, 2003; October 26, 2012; May 7, 2013; January 28, 2004; June 10, 2004; April 15, 2014 April 21, 2005; December 15, 2005; October 26, 2012; May 7, 2013; April 15, 2014 Current Effective Date: April 15, 2014 Current Effective Date: April 15, 2014 State and Federal mandates and health plan member contract language, including specific provisions/exclusions, take precedence over Medical Policy and must be considered first in determining eligibility for coverage. To verify a member's benefits, contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Customer Service. The BCBSKS Medical Policies contained herein are for informational purposes and apply only to members who have health insurance through BCBSKS or who are covered by a self-insured group plan administered by BCBSKS. Medical Policy for FEP members is subject to FEP medical policy which may differ from BCBSKS Medical Policy. The medical policies do not constitute medical advice or medical care. Treating health care providers are independent contractors and are neither employees nor agents of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas and are solely responsible for diagnosis, treatment and medical advice. If your patient is covered under a different Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan, please refer to the Medical Policies of that plan. -

Iliopsoas Tendonitis/Bursitis Exercises

ILIOPSOAS TENDONITIS / BURSITIS What is the Iliopsoas and Bursa? The iliopsoas is a muscle that runs from your lower back through the pelvis to attach to a small bump (the lesser trochanter) on the top portion of the thighbone near your groin. This muscle has the important job of helping to bend the hip—it helps you to lift your leg when going up and down stairs or to start getting out of a car. A fluid-filled sac (bursa) helps to protect and allow the tendon to glide during these movements. The iliopsoas tendon can become inflamed or overworked during repetitive activities. The tendon can also become irritated after hip replacement surgery. Signs and Symptoms Iliopsoas issues may feel like “a pulled groin muscle”. The main symptom is usually a catch during certain movements such as when trying to put on socks or rising from a seated position. You may find yourself leading with your other leg when going up the stairs to avoid lifting the painful leg. The pain may extend from the groin to the inside of the thigh area. Snapping or clicking within the front of the hip can also be experienced. Do not worry this is not your hip trying to pop out of socket but it is usually the iliopsoas tendon rubbing over the hip joint or pelvis. Treatment Conservative treatment in the form of stretching and strengthening usually helps with the majority of patients with iliopsoas bursitis. This issue is the result of soft tissue inflammation, therefore rest, ice, anti- inflammatory medications, physical therapy exercises, and/or injections are effective treatment options. -

Right Ring Finger Volar Mass in a 14-Year-Old

6/6/2017 Right Ring Finger Volar Mass in a 14YearOld Boy CASE REPORT FREE Right Ring Finger Volar Mass in a 14YearOld Boy Mary P. Fox, MD; Jack E. McKay, MD; Randall D. Craver, MD; Nicholas D. Pappas, MD Orthopedics Posted May 22, 2017 DOI: 10.3928/014774472017051801 Abstract A trigger digit is relatively uncommon in adolescents and often has a different etiology in that age group vs adults. In the pediatric population, trigger digits frequently arise from a variety of underlying anatomic situations, including thickening of the flexor digitorum superficialis or flexor digitorum profundus tendons, an abnormal relationship between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus tendons, a proximal flexor digitorum superficialis decussation, or constriction of the pulleys. In addition, underlying conditions such as mucopolysaccharidosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, EhlersDanlos syndrome, and central nervous system disorders such as delayed motor development have been associated with triggering. Less commonly, triggering secondary to intratendinous or peritendinous calcifications or granulations has been described, which is what occurred in the current case. This report describes a case of tenosynovitis with psammomatous calcification treated with excision of the mass from the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon and release of both the A1 and palmar aponeurosis pulleys in an adolescent patient. [Orthopedics. 201x; xx(x):xx–xx.] The etiology for a trigger digit in the adolescent population can be complex and extensive, including underlying anatomic causes or other pathological processes such as fracture, tumor, or traumatic soft tissue injuries.1–5 Current literature has not described a case of tenosynovitis secondary to a peritendinous soft tissue mass consisting of psammomatous calcification in the adolescent population. -

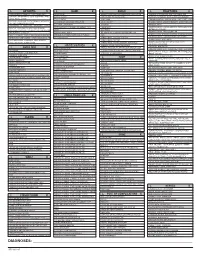

ICD-10 Diagnoses on Router

L ARTHRITIS R L HAND R L ANKLE R L FRACTURES R OSTEOARTHRITIS: PRIMARY, 2°, POST TRAUMA, POST _____ CONTUSION ACHILLES TEN DYSFUNCTION/TENDINITIS/RUPTURE FLXR TEN CLAVICLE: STERNAL END, SHAFT, ACROMIAL END CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: GOUT: IDIOPATHIC, LEAD, CRUSH INJURY AMPUTATION TRAUMATIC LEVEL SCAPULA: ACROMION, BODY, CORACOID, GLENOID DRUG, RENAL, OTHER DUPUYTREN’S CONTUSION PROXIMAL HUMERUS: SURGICAL NECK 2 PART 3 PART 4 PART CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: PSEUDOGOUT: HYDROXY LACERATION: DESCRIBE STRUCTURE CRUSH INJURY PROXIMAL HUMERUS: GREATER TUBEROSITY, LESSER TUBEROSITY DEP DIS, CHONDROCALCINOSIS LIGAMENT DISORDERS EFFUSION HUMERAL SHAFT INFLAMMATORY: RA: SEROPOSITIVE, SERONEGATIVE, JUVENILE OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ LOOSE BODY HUMERUS DISTAL: SUPRACONDYLAR INTERCONDYLAR REACTIVE: SECONDARY TO: INFECTION ELSEWHERE, EXTENSION OR NONE INTESTINAL BYPASS, POST DYSENTERIC, POST IMMUNIZATION PAIN OCD TALUS HUMERUS DISTAL: TRANSCONDYLAR NEUROPATHIC CHARCOT SPRAIN HAND: JOINT? OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ HUMERUS DISTAL: EPICONDYLE LATERAL OR MEDIAL AVULSION INFECT: PYOGENIC: STAPH, STREP, PNEUMO, OTHER BACT TENDON RUPTURES: EXTENSOR OR FLEXOR PAIN HUMERUS DISTAL: CONDYLE MEDIAL OR LATERAL INFECTIOUS: NONPYOGENIC: LYME, GONOCOCCAL, TB TENOSYNOVITIS SPRAIN, ANKLE, CALCANEOFIBULAR ELBOW: RADIUS: HEAD NECK OSTEONECROSIS: IDIOPATHIC, DRUG INDUCED, SPRAIN, ANKLE, DELTOID POST TRAUMATIC, OTHER CAUSE SPRAIN, ANKLE, TIB-FIB LIGAMENT (HIGH ANKLE) ELBOW: OLECRANON WITH OR WITHOUT INTRA ARTICULAR EXTENSION SUBLUXATION OF ANKLE, -

Pes Anserine Bursitis

BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Pes Anserine Bursitis ICD 9 Codes: 726.61 Case Type / Diagnosis: The pes anserine bursa lies behind the medial hamstring, which is composed of the tendons of the sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus (SGT) muscles. Because these 3 tendons splay out on the anterior aspect of the tibia and give the appearance of the foot of a goose, pes anserine bursitis is also known as goosefoot bursitis.1 These muscles provide for medial stabilization of the knee by acting as a restraint to excessive valgus opening. They also provide a counter-rotary torque function to the knee joint. The pes anserine has an eccentric role during the screw-home mechanism that dampens the effect of excessively forceful lateral rotation that may accompany terminal knee extension.2 Pes anserine bursitis presents as pain, tenderness and swelling over the anteromedial aspect of the knee, 4 to 5 cm below the joint line.3 Pain increases with knee flexion, exercise and/or stair climbing. Inflammation of this bursa is common in overweight, middle-aged women, and may be associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. It also occurs in athletes engaged in activities such as running, basketball, and racquet sports.3 Other risk factors include: 1 • Incorrect training techniques, or changes in terrain and/or distanced run • Lack of flexibility in hamstring muscles • Lack of knee extension • Patellar malalignment Indications for Treatment: • Knee Pain • Knee edema • Decreased active and /or passive ROM of lower extremities • Biomechanical dysfunction lower extremities • Muscle imbalances • Impaired muscle performance (focal weakness or general conditioning) • Impaired function Contraindications: • Patients with active signs/symptoms of infection (fever, chills, prolonged and obvious redness or swelling at hip joint). -

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile joint in the human body, but this same characteristic also makes it the least stable joint.1-3 The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that are important in supporting the glenohumeral joint, essential in almost every type of shoulder movement.4 These muscles maintain dynamic joint stability which not only avoids mechanical obstruction but also increases the functional range of motion at the joint.1,2 However, dysfunction of these stabilizers often leads to a complex pattern of degeneration, rotator cuff tear arthropathy that often involves subacromial impingement.2,22 Rotator cuff tear arthropathy is strikingly prevalent and is the most common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction.3,4 It appears to be age-dependent, affecting 9.7% of patients aged 20 years and younger and increasing to 62% of patients of 80 years and older ( P < .001); odds ratio, 15; 95% CI, 9.6-24; P < .001.4 Etiology for rotator cuff pathology varies but rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy are most common in athletes and the elderly.12 It can be the result of a traumatic event or activity-based deterioration such as from excessive use of arms overhead, but some argue that deterioration of these stabilizers is part of the natural aging process given the trend of increased deterioration even in individuals who do not regularly perform overhead activities.2,4 The factors affecting the rotator cuff and subsequent treatment are wide-ranging. The major objectives of this exposition are to describe rotator cuff anatomy, biomechanics, and subacromial impingement; expound upon diagnosis and assessment; and discuss surgical and conservative interventions. -

Elbow Checklist

Workbook Musculoskeletal Ultrasound September 26, 2013 Shoulder Checklist Long biceps tendon Patient position: Facing the examiner Shoulder in slight medial rotation; elbow in flexion and supination Plane/ region: Transverse (axial): from a) intraarticular portion to b) myotendinous junction (at level of the pectoralis major tendon). What you will see: Long head of the biceps tendon Supraspinatus tendon Transverse humeral ligament Subscapularis tendon Lesser tuberosity Greater tuberosity Short head of the biceps Long head of the biceps (musculotendinous junction) Humeral shaft Pectoralis major tendon Plane/ region: Logitudinal (sagittal): What you will see: Long head of biceps; fibrillar structure Lesser tuberosity Long head of the biceps tendon Notes: Subscapularis muscle and tendon Patient position: Facing the examiner Shoulder in lateral rotation; elbow in flexion/ supination Plane/ region: longitudinal (axial): full vertical width of tendon. What you will see: Subscapularis muscle, tendon, and insertion Supraspinatus tendon Coracoid process Deltoid Greater tuberosity Lesser tuberosity Notes: Do passive medial/ lateral rotation while examining Plane/ region: Transverse (sagittal): What you will see: Lesser tuberosity Fascicles of subscapularis tendon Supraspinatus tendon Patient position: Lateral to examiner Shoulder in extension and medial rotation Hand on ipsilateral buttock Plane/ region: Longitudinal (oblique sagittal) Identify the intra-articular portion of biceps LH in the transverse plane; then -

Gluteal Tendinopathy

Gluteal Tendinopathy What is a Gluteal Tendinopathy? In lying Up until recently hip bursitis was diagnosed as the main Either on your bad hip or with bad cause of lateral hip pain but recent studies suggest that an hip hanging across body like so irritation of the gluteus muscle tendon is the likeliest cause. The tendon attaches onto a bony prominence (greater trochanter) and it is here that the tendon is subject to All these positions lead to increase friction of the tendon, compressive forces leading to irritation. can cause pain and slow the healing process. This can result in pain over the lateral hip which can refer down the outside For sleeping you might like to try these positions: of the thigh and into the knee. How common is it? Gluteal tendinopathy is relatively common affecting 10-25% of the population. It is 3 times more prevalent in women than men and is most common in women between the ages of 40 and 60. One of the reasons for this is women It is also important to modify your activity. Avoid or reduce tend to have a greater angle at their hip joint increasing things that flare up your pain, this could be climbing stairs compressive forces on the tendon. or hills or those longer walks/runs. Signs and Symptoms Exercise Therapy • Pain on the outside of your hip, can refer down outside of the thigh to the knee This is best administered by a Physiotherapist to suit the • Worse when going up and/or down stairs individual but below is a rough guide to exercises which • Worse lying on affected side (and sometimes on the can help a gluteal tendinopathy. -

Intramuscular Neural Distribution of the Sartorius Muscles: Treating Spasticity with Botulinum Neurotoxin

Intramuscular Neural Distribution of the Sartorius Muscles: Treating Spasticity With Botulinum Neurotoxin Kyu-Ho Yi Yonsei University Ji-Hyun Lee Yonsei University Kyle Seo Modelo Clinic Hee-Jin Kim ( [email protected] ) Yonsei University Research Article Keywords: botulinum neurotoxin, spasticity, sartorius muscle, Sihler’s staining Posted Date: January 6th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-129928/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract This study aimed to detect the idyllic locations for botulinum neurotoxin injection by analyzing the intramuscular neural distributions of the sartorius muscles. A altered Sihler’s staining was conducted on sartorius muscles (15 specimens). The nerve entry points and intramuscular arborization areas were measured as a percentage of the total distance from the most prominent point of the anterior superior iliac spine (0%) to the medial femoral epicondyle (100%). Intramuscular neural distribution were densely detected at 20–40% and 60–80% for the sartorius muscles. The result suggests that the treatment of sartorius muscle spasticity requires botulinum neurotoxin injections in particular locations. These locations, corresponding to the locations of maximum arborization, are suggested as the most safest and effective points for botulinum neurotoxin injection. Introduction Spasticity is a main contributor to functional loss in patients with impaired central nervous system, such as in stroke, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, and others 1. Sartorius muscle, as a hip and knee exor, is one of the commonly involved muscles, and long-lasting spasticity of the muscle results in abnormalities secondary to muscle hyperactivity, affecting lower levels of functions, such as impairment of gait. -

Giant Cell Tumor of the Pes Anserine Bursa (Extra-Articular Pigmented Villonodular Bursitis): a Case Report and Review of the Literature

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Medicine Volume 2011, Article ID 491470, 6 pages doi:10.1155/2011/491470 Case Report Giant Cell Tumor of the Pes Anserine Bursa (Extra-Articular Pigmented Villonodular Bursitis): A Case Report and Review of the Literature Haitao Zhao,1 Aditya V. Maheshwari,2, 3 Dhruv Kumar,4 and Martin M. Malawer2, 5 1 Department of Orthopedic Oncology, Beijing JiShui Tan Hospital, Peking University, 31 Xinjiekou East Street, Xicheng District, Beijing 100035, China 2 Department of Orthopedic Oncology, Washington Hospital Center, 110 Irving Street North West, Washington, DC 20010, USA 3 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, 450 Clarkson Avenue, P.O. Box 30, Brooklyn, NY 11203, USA 4 Department of Pathology, Washington Hospital Center, 110 Irving Street North West, Washington, DC 20010, USA 5 Department of Orthopedic Oncology, The George Washington University Hospital, 900 23rd Street North West, Washington, DC 20037, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Haitao Zhao, [email protected] Received 14 February 2011; Accepted 7 April 2011 Academic Editor: Edward V. Craig Copyright © 2011 Haitao Zhao et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a rare, benign, proliferating disease affecting the synovium of joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths. Involvement of bursa (PVNB, pigmented villonodular bursitis) is the least common, and only few cases of exclusively extra-articular PVNB of the pes anserinus bursa have been reported so far. We report a case of extra-articular pes anserine PVNB along with a review of the literature. -

Spontaneous Septic Subacromial Bursitis Due to Streptococcus

A Case Report: Spontaneous Septic Subacromial Bursitis Due to Streptococcus anginosus Emily McGhee, MD, Mohammad Agha, MD, MHA University of Missouri – Columbia Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Introduction: Discussion: • 67 year old male presented to clinic with 1-2 weeks • Septic subacromial bursitis is rare due to the nature of right shoulder pain, 8/10 achy, no radiation, of the anatomic location of the deep bursa¹ worse with flexion and extension, improved with ice • It is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, • Gastroenteritis 3 days prior with fever of 102°F and after corticosteroid injections, or if there is a vomiting hematogenous spread from another source² • History is significant for HTN, T2DM, OA, bilateral • Of the cases reported in literature, 80% are caused total knee replacements, previous tobacco user, by Staphylococcus aureus² allergies to penicillin and sulfa • Streptococcus anginosus is part of the normal flora of the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract • It can spread hematogenously and is known for its Clinical Course: ability to cause abscesses • Physical Exam: Vital signs within normal limits. • Streptococcus anginosus has been seen in pubic Right shoulder active abduction 30°, passive symphysis and sternoclavicular joint infections3,4 abduction 80°, 4/5 external and internal rotation, • There have been no reported cases of remainder of exam deferred due to pain. Normal left Figure 1: T2 weighted MRI Right Shoulder - large Streptococcus anginosus causing septic shoulder exam subacromial bursitis fluid collection in subacromial/subdeltoid bursa, • Diagnosed with rotator cuff tear and started physical appears ruptured with fluid extending laterally therapy Conclusion: • Initial x-ray negative, lab work unremarkable along humeral shaft, synovial thickening and • Pain continued, prompting a clinic visit the next day enhancement.