Designing the Key Stage 3 Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(PDF) Understanding the Foundation Stage

Contents Introduction 1 The Rationale of the Foundation Stage • The Characteristics of the Foundation Stage 2 • The Aims of the Foundation Stage 3 • The Principles Underpinning the Foundation Stage 4 • The Curriculum in the Foundation Stage 5 Creating an Effective Learning Environment • The Approach to Learning and Teaching in the Foundation Stage 6 • Adults’ Role in Promoting Learning 7 • Learning Partnerships 7 • The Physical Environment 8 Learning, Teaching and Assessment • The Learning, Teaching and Assessment Cycle in the Foundation Stage 9 • Planning in the Foundation Stage 11 • Assessment for Learning in the Foundation Stage 13 • Observation and Assessment in the Foundation Stage 13 • The Pupil Profile in the Foundation Stage 15 Acknowledgements This material has been developed in collaboration with the Early Years Interboard Group. Understanding the Foundation Stage Introduction The Foundation Stage Years 1 & 2 in the primary school The purpose of this guidance is to provide information related to good practice in the Foundation Stage. It outlines the approach to learning, teaching and assessment and should be used to support the review, development and improvement of existing provision and practice. Young children come to school from a variety of different backgrounds, having had a range of diverse learning experiences at home and for most, some form of pre-school education. The Foundation Stage aims to build on these learning experiences by providing children with an appropriate learning programme to develop their dispositions to learn and to provide them with the skills and competencies they will need to succeed in school and future life. The Foundation Stage also endorses good early years practice where teachers have more flexibility in terms of what they teach. -

An Evaulation of Key Stage 3 2007

An Evaluation of Key Stage 3 2007 S13/2007 November 2007 FAMILY AND CHILDREN’S SERVICES POLICY AND PERFORMANCE KEY STAGE 3, 2007 Research Report S13/2007 This research report presents an analysis of Key Stage 3 results in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in 2007. Results are compared with statistical neighbours and the national averages, and with previous years. Results are presented by school and are contextualised by gender, entitlement to receive a free school meal, SEN, ethnicity, time in school, term of birth, IDACI and pupils’ attendance. The Royal Borough’s results are compared with the 2007 national average and with previous years. The results of a ‘value-added’ assessment of pupil achievement at Key Stage 3 (2007) are presented, using pupils’ previous achievement at Key Stage 2 (2004) as the baseline measure. Further Sam Utting or Diana Hall information available from: Telephone: 0207 361 3096 or 0207 598 4815 Policy and Performance welcomes your comments on this and other reports, and any suggestions for future research. KEY STAGE 3 2007 CONTENTS Paragraph numbers: 1 Introduction 2 The requirements of Key Stage 3 Statutory Assessment in 2007. 3 The structure of Key Stage 3 Assessment in 2007. 4 Evaluation of Key Stage 3 Targets in 2007. 5 Summary of results 6 Borough level results 7 Holland Park 8 St Thomas More 9 Sion Manning 10 Cardinal Vaughan 11 Factors affecting performance (borough level) 12 Ethnicity 13 Attendance 14 Key Stage 2 (2004) to Key Stage 3 (2007) 15 Looked After Children 16 Conclusion 17 Recommendations -

The Sciences at Key Stage 4: Time for a Re-Think? Why Key Stage 4 Is So Important, and Why Changes Are Needed

The sciences at key stage 4: time for a re-think? Why key stage 4 is so important, and why changes are needed Key stage 4 is a pivotal period of time in a student’s chemistry and biology are currently the preserve of school life; it is the point at which they make subject a minority. There is evidence that the existence of choices that define their future study, as well as their multiple routes through key stage 4 disadvantages a last experience of those subjects that they do not large number of students in both their experiences and choose to take further. The sciences are core subjects the choices that are taken away from them. For this to 16, yet multiple qualifications exist for students reason, the SCORE organisations are proposing that of this age. As this discussion paper documents, there should be a single route in the sciences for all evidence suggests that rich opportunities in physics, students up to the age of 16. SCORE’sSCORE’s proposal: proposal: a asingle single route route in in the the sciences sciences SCORE’sSCORE’s vision vision is thatis that opportunities opportunities for forhigh-quality high-quality studyexciting of the sciences and inspiring are available experience to all, of onthe an sciences, studyequitable of the sciencesbasis, and are we available believe thatto all, this on can an only be achievedproviding by the them creation with ofthe a skillssingle and route knowledge at key to equitablestage 4. basis, This singleand we route believe would that remove this can the only need for decisionssucceed to be in madetheir future at 14 endeavours,that could limit whether students’ or not be futureachieved choices, by the and creation give all of students a single routean authentic, at key excitingthey and decideinspiring to experience pursue the ofsciences the sciences, beyond 16. -

Social Selectivity of State Schools and the Impact of Grammars

_____________________________________________________________________________ Social selectivity of state schools and the impact of grammars A summary and discussion of findings from ‘Evidence on the effects of selective educational systems’ by the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University The Sutton Trust, October 2008 Contents Executive summary 3 Introduction and background 5 Findings -- selectivity 7 Findings – pupil intakes 10 Findings – attainment 12 Discussion 13 Proposed ways forward 16 Appendix 18 2 Executive summary Overview This study shows that the vast majority of England's most socially selective state secondary schools are non-grammar schools. However, England's remaining grammar schools are enrolling half as many academically able children from disadvantaged backgrounds as they could do. The research also concludes that the impact on the academic results of non-grammar state schools due to the ‘creaming off’ of pupils to grammar schools is negligible. Grammars have a widespread, low-level, impact on pupil enrolments across the sector. A relatively small number of non-selective schools do see a significant proportion of pupils ‘lost’ to nearby grammars, but this does not lead to lower academic achievement. The Trust proposes that a further study be undertaken to review ‘eleven plus’ selection tests to see whether they deter bright pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds applying to grammar schools, and urges more grammars to develop outreach schemes to raise the aspirations and achievement of children during primary school. It also backs calls for religious schools to consider straightforward 'binary' criteria to decide which pupils should be admitted on faith grounds, and other ways – including the use of banding and ballots – to help make admissions to all secondary state schools operate more equitably. -

Early Years – Key Stage 4

Public Oral Health CURRIC ULUM TOOL KIT WWW... Early Years – Key Stage 4 Oral Health Promotion Team Derby City and Derbyshire County Public Contents • Introduction Page 2 • Oral Health messages Pages 3-5 • Oral Health links to the Early Years Foundation Stage Page 7 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 1 Page 9 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 2 Page 10 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 3 Page 11 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 4 Page 12 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Early Years - Key Stage 4 Page 14 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Special Educational Page 15 Needs and Disabilities and English as an Additional Language • Borrowing resources Page 16 • Purchasing Resources Page 17 • Apps available to download Page 18 1 Public Introduction Schools provide an important setting for promoting health which can easily be integrated into general health promotion, school curriculum and activities. Health promoting messages can be reinforced throughout the most influential stages of children’s lives, enabling them to develop lifelong sustainable attitudes, behaviours and skills. The health and wellbeing of school staff, families and community members can also be enhanced by programmes based in schools. Oral health is fundamental to general health and wellbeing. A healthy mouth enables an individual to speak, eat and socialize without experiencing active disease, discomfort or embarrassment. Poor oral health impacts on children’s confidence, language and personal, social and emotional development. Tackling poor oral health is a priority for Public Health England (PHE) under the national priority of ensuring that every child has the Best Start in Life. -

Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project

Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project August 2005 Prepared by Keith Fuller (Senior Consultant) Frank Thomas (Associate Consultant) Colin Horswell Mouchel Parkman Strelley Hall Nottingham NG8 6PE T +44 (0)115 9061 313 F +44 (0)115 9061 302 Prepared for KS2-3 Transition Design Collaborative Steering Group Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the staff and pupils of the following for their co-operation and support in the compilation of this report. Seven Kings High School (Redbridge); Valentines High School (Redbridge); Archbishop Tenison’s C of E High School (Croydon); Norbury Manor High School for Girls (Croydon); Jo Richardson Community School (Barking and Dagenham); Haydon School (Hillingdon); Rutlish School (Merton); Preston Manor High School (Brent); Battersea Technology College (Wandsworth); Lady Margaret School (Hammersmith and Fulham); Stockwell Park School (Lambeth); Highbury Fields School (Islington); Stanley Park High School (Sutton); Park View Academy (Haringey); Tolworth Girls’ School (Kingston-upon-Thames); The Ravensbourne School (Bromley); Little Ilford School (Newham). Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................1 2 Methodology ...............................................................................................3 2.1 The questionnaire and interviews in schools.................................................3 2.2 Good practice -

Opening a Studio School a Guide for Studio School Proposer Groups on the Pre-Opening Stage

Opening a studio school A guide for studio school proposer groups on the pre-opening stage August 2014 Contents Introduction 3 Section 1 - Who does what - roles and responsibilities? 5 Section 2 - Managing your project 10 Section 3 – Governance 12 Section 4 - Pupil recruitment and admissions 21 Section 5 - Statutory consultation 33 Section 6 - Staffing and education plans 36 Section 7 - Site and buildings 42 Section 8 – Finance 56 Section 9 - Procurement and additional support 63 Section 10 - Funding Agreement 67 Section 11 - The equality duty 71 Section 12 - Preparing to open 73 Section 13 - Once your school is open 80 Annex A - RSC regions and Local authorities 82 2 Introduction Congratulations! All your planning and preparation has paid off, and the Secretary of State for Education has agreed that your application to open a studio school should move to the next stage of the process – known as the ‘pre-opening’ stage. This is the stage between the approval of your application and the opening of the school. The setting up of a studio school is a challenging but ultimately very rewarding task and it will require significant commitment and time from sponsors and partners. Your original application set out your plans for establishing the studio school, from the education vision and the admission of pupils to the recruitment of staff and the curriculum. Now your application has been approved, you must begin work to implement these plans. The letter of approval you received from the Department for Education (DfE) sets out important conditions of approval. It is vital that you consider these conditions carefully in planning your priorities and what you need to focus on next. -

The National Curriculum in England Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document

The national curriculum in England Key stages 1 and 2 framework document September 2013 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. The school curriculum in England 5 3. The national curriculum in England 6 4. Inclusion 8 5. Numeracy and mathematics 9 6. Language and literacy 10 7. Programmes of study and attainment targets 12 English 13 Spoken language – years 1 to 6 17 Key stage 1 – year 1 19 Key stage 1 – year 2 26 Lower key stage 2 – years 3 and 4 33 Upper key stage 2 – years 5 and 6 41 English Appendix 1: Spelling 49 Spelling – work for year 1 50 Spelling – work for year 2 55 Spelling – work for years 3 and 4 59 Word list – years 3 and 4 64 Spelling – years 5 and 6 66 Word list – years 5 and 6 71 International Phonetic Alphabet (non-statutory) 73 English Appendix 2: Vocabulary, grammar and punctuation 74 Glossary for the programmes of study for English (non-statutory) 80 Mathematics 99 Key stage 1 – years 1 and 2 101 Year 1 programme of study 102 Year 2 programme of study 107 Lower key stage 2 – years 3 and 4 113 Year 3 programme of study 114 Year 4 programme of study 120 2 Upper key stage 2 – years 5 and 6 126 Year 5 programme of study 127 Year 6 programme of study 135 Mathematics Appendix 1: Examples of formal written methods for addition, subtraction, multiplication and division 142 Science 144 Key stage 1 146 Key stage 1 programme of study – years 1 and 2 147 Year 1 programme of study 148 Year 2 programme of study 151 Lower key stage 2 – years 3 and 4 154 Lower key stage 2 programme of study 155 Year 3 programme of study 157 Year 4 programme of study 161 Upper key stage 2 – years 5 and 6 165 Upper key stage 2 programme of study 166 Year 5 programme of study 168 Year 6 programme of study 172 Art and design 176 Computing 178 Design and technology 180 Geography 184 History 188 Languages 193 Music 196 Physical education 198 3 1. -

Key Stage 3 Curriculum for Years 7, 8 & 9

Key Stage 3 2014 Key Stage 3 Curriculum for Years 7, 8 & 9 HITCHIN BOYS’ SCHOOL, GRAMMAR SCHOOL WALK, HITCHIN, HERTFORDSHIRE. SG5 1JB ART AND DESIGN Name of Head of Department: Mrs D Aldin-Burnett (from whom further information may be obtained) Teachers: Mrs O Konanec Mrs H Scripps Mrs G Anderson Miss K Rainbow Art Technician Mrs D Ward Number of teaching periods per week: Year 7 2 (One hour periods) Year 8 1 Year 9 1 Homework: Homework is set in line with the whole-school policy. It may involve such tasks as internet research about particular artists, collecting source material or working in sketch books. Method of assessment: Year 7: Assessment at the end of each unit of work (3 units per year) + examination in June. Year 8: Assessment at the end of each unit of work (3 units per year) + examination in June. Year 9: Assessment at the end of each unit of work (3 units per year) + examination in June. Details of field trips or visits: Visits will be arranged to local galleries and museum. All visits form part of the syllabus. Visits will relate to topics undertaken in class. Details of special equipment or clothing needed with approximate costs: Pupils are advised to wear some form of protective clothing. An overall, apron or old shirt will be adequate. Staff and other pupils cannot be held responsible for clothing accidentally damaged. An A4 book and portfolio will be issued at the beginning of each KS3 year. Pupils taking GCSE will be asked to purchase an A3 book for the 4 units throughout the 2 years. -

Supporting Transition from Reception to Year 1 (Following Break in Schooling Due to Covid-19)

SUPPORTING TRANSITION FROM RECEPTION TO YEAR 1 (FOLLOWING BREAK IN SCHOOLING DUE TO COVID-19) Page 1 of 40 © EARLY YEARS MATTERS LTD EMAIL: [email protected] SUPPORTING TRANSITION FROM RECEPTION TO YEAR 1 (POST-COVID BREAK IN SCHOOLING) Prior to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic schools and Ofsted were looking closely at issues around transition from EYFS into Key Stage 1. Arguably, this was because it was clear that unless and until the divide between these two important stages was bridged children were losing out – going from an informal and active approach to a more sedentary seat-based approach. This was further complicated by the fact that: ‘Reception and Year 1 teachers agreed that the vital, smooth transition from the foundation stage to Year 1 was difficult because the early learning goals were not aligned with the now-increased expectations of the national curriculum.’ (Ofsted, 2017). To date, due to the pandemic, much remains in abeyance and even the requirement to complete the EYFSP, has been suspended, leaving teachers with less information than ever as children who have completed less than two terms in Reception classes prepare to move into Year 1 in September 2020. A further and more complicated issue, is not only that children have missed out on vital schooling, but that they have done so in a period of uncertainty when adults, themselves are confused and fearful about the effects of the pandemic. This booklet is therefore intended to support EYFS and Year 1 leaders and teachers as they negotiate the ‘normal’ transition questions and the ‘new normal’ ones such as how to make up for lost learning time, how to manage resources, where to start, and so on. -

Year One Children's Literacy Behaviours and Perceptions of Literacy Learning in the Classroom and Reading Recovery Contexts

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2002 Year one children's literacy behaviours and perceptions of literacy learning in the classroom and reading recovery contexts Fiona Callaghan Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Callaghan, F. (2002). Year one children's literacy behaviours and perceptions of literacy learning in the classroom and reading recovery contexts. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/740 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/740 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

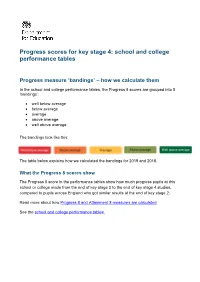

Progress Scores for Key Stage 4: School and College Performance Tables

Progress scores for key stage 4: school and college performance tables Progress measure ‘bandings’ – how we calculate them In the school and college performance tables, the Progress 8 scores are grouped into 5 ‘bandings’: • well below average • below average • average • above average • well above average The bandings look like this: The table below explains how we calculated the bandings for 2019 and 2018. What the Progress 8 scores show The Progress 8 score in the performance tables show how much progress pupils at this school or college made from the end of key stage 2 to the end of key stage 4 studies, compared to pupils across England who got similar results at the end of key stage 2. Read more about how Progress 8 and Attainment 8 measures are calculated See the school and college performance tables. How we calculated the bandings for 2019 and 2018 Progress A school/college1 was given the description if… description The progress score is 0.5 or higher, and lower confidence interval limit Well above is higher than 0. average 2019: About 14% of schools/colleges in England 2018: About 14% of schools/colleges in England The progress score is higher than 0 but lower than 0.5, and lower confidence interval limit is higher than 0. Above average 2019: About 17% of schools/colleges in England 2018: About 17% of schools/colleges in England The progress score has a confidence interval that includes 0. That is, the score’s lower confidence interval limit is 0 or less and/or the Average score’s upper confidence interval limit is 0 or more.