Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures the Syriac Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theodora, Aetius of Amida, and Procopius: Some Possible Connections John Scarborough

Theodora, Aetius of Amida, and Procopius: Some Possible Connections John Scarborough HEN ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL SOURCES speak of prostitutes’ expertise, they frequently address the Wquestion of how they managed to keep free from pregnancies. Anyone unschooled in botanicals that were con- traceptives or abortifacients might pose a question similar to that of an anonymous writer in twelfth-century Salerno who asks medical students: “As prostitutes have very frequent intercourse, why do they conceive only rarely?”1 Procopius’ infamous invective, describing the young Theodora’s skills in prostitution, contains a similar phrase: she “became pregnant in numerous instances, but almost always could expel instantly the results of her coupling.”2 Neither text specifies the manner of abortion or contraception, probably similar to those re- corded in the second century by Soranus of Ephesus (see be- low). Procopius’ deliciously scandalous narrative is questionable 1 Brian Lawn, The Prose Salernitan Questions (London 1970) B 10 (p.6): Que- ritur cum prostitute meretrices frequentissime coeant, unde accidat quod raro concipiant? 2 Procop. Anec. 9.19 (ed. Haury): καὶ συχνὰ µὲν ἐκύει, πάντα δὲ σχεδὸν τεχνάζουσα ἐξαµβλίσκειν εὐθὺς ἴσχυε, which can also be translated “She conceived frequently, but since she used quickly all known drugs, a mis- carriage was effected”; if τεχνάζουσα is the ‘application of a specialized skill’, the implication becomes she employed drugs that were abortifacients. Other passages suggestive of Procopius’ interests in medicine and surgery include Wars 2.22–23 (the plague, adapted from Thucydides’ description of the plague at Athens, with the added ‘buboes’ of Bubonic Plague, and an account of autopsies performed by physicians on plague victims), 6.2.14–18 (military medicine and surgery), and 1.16.7 (the infamous description of how the Persians blinded malefactors, reported matter-of-factly). -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Instruction Manual

IINNSSTTRRUUCCTTIIOONN MMAANNUUAALL NexStar 60 . NexStar 80 . NexStar 102 . NexStar 114 . NexStar 130 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Warning .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 ASSEMBLY ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Assembling the NexStar ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Attaching the Hand Control Holder ............................................................................................................................ 8 Attaching the Fork Arm to the Tripod......................................................................................................................... 8 Attaching the Telescope to the Fork Arm ................................................................................................................... 8 The Star Diagonal ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 The Eyepiece.............................................................................................................................................................. -

Janus Cornarius Éditeur Et Commentateur Du Traité De Galien Sur La Composition Des Médicaments Selon Les Lieux

Janus Cornarius éditeur et commentateur du traité de Galien Sur la composition des médicaments selon les lieux alessia guardasole CNRS Paris The Saxon humanist Janus Cornarius (ca. 1500–1558) devoted himself to edit, translate, and comment the extant works of Galen of Pergamon (129–ca. 216). In this study I deal with the Latin translation and commentary of Galen’s work On the composition of drugs by site, edited by Cornarius (Basel, 1537). Namely, by investigating some passages of Galen’s treatise, my effort is to throw light on Cornarius’ working method, defining which literary and manuscript sources he used to improve and interpret thoroughly Galen’s text. e grand travail philologique qui fit suite à l’ édition princeps des œuvres de LGalien chez les Aldes en 1525 s’ enrichit considérablement avec l’ activité extrêmement féconde de Janus Cornarius1. Après avoir acquis en 1535 l’édition Aldine de Galien, Cornarius consacra son travail d’interprétation aux traités galéniques qui n’avaient pas encore suscité l’intérêt des autres traducteurs, en choisissant premièrement les œuvres sur la respiration en raison de son importance physiologique (rem sine qua vivere non possumus), et deuxièmement sur la procréation2 en raison vraisemblablement des liens doctrinaux que l’on pouvait trouver avec les œuvres d’Hippocrate au sujet de la procréation et des affections de la femme. Notre étude sera consacrée au travail du médecin allemand sur les textes galéniques qui a immédiatement suivi, à savoir l’ édition de prestige dédiée à Albert de Mayence qui contient la traduction des dix livres du traité Sur la composition des médicaments selon les lieux3 (que j’ appellerai désormais Secundum locos), publiée à Bâle chez Froben en 1537 et enrichie de façon tout à fait exceptionnelle par un commentaire continu de l’ouvrage de pharmacologie4, dans lequel Cornarius déploie tout son savoir philologique et médical. -

Classical and Modern Standard Arabic Marijn Van Putten University of Leiden

Chapter 3 Classical and Modern Standard Arabic Marijn van Putten University of Leiden The highly archaic Classical Arabic language and its modern iteration Modern Standard Arabic must to a large extent be seen as highly artificial archaizing reg- isters that are the High variety of a diglossic situation. The contact phenomena found in Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic are therefore often the re- sult of imposition. Cases of borrowing are significantly rarer, and mainly found in the lexical sphere of the language. 1 Current state and historical development Classical Arabic (CA) is the highly archaic variety of Arabic that, after its cod- ification by the Arab Grammarians around the beginning of the ninth century, becomes the most dominant written register of Arabic. While forms of Middle Arabic, a style somewhat intermediate between CA and spoken dialects, gain some traction in the Middle Ages, CA remains the most important written regis- ter for official, religious and scientific purposes. From the moment of CA’s rise to dominance as a written language, the whole of the Arabic-speaking world can be thought of as having transitioned into a state of diglossia (Ferguson 1959; 1996), where CA takes up the High register and the spoken dialects the Low register.1 Representation in writing of these spoken dia- lects is (almost) completely absent in the written record for much of the Middle Ages. Eventually, CA came to be largely replaced for administrative purposes by Ottoman Turkish, and at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was function- ally limited to religious domains (Glaß 2011: 836). -

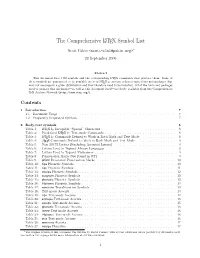

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List Scott Pakin <[email protected]>∗ 22 September 2005 Abstract This document lists 3300 symbols and the corresponding LATEX commands that produce them. Some of these symbols are guaranteed to be available in every LATEX 2ε system; others require fonts and packages that may not accompany a given distribution and that therefore need to be installed. All of the fonts and packages used to prepare this document—as well as this document itself—are freely available from the Comprehensive TEX Archive Network (http://www.ctan.org/). Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Document Usage . 7 1.2 Frequently Requested Symbols . 7 2 Body-text symbols 8 Table 1: LATEX 2ε Escapable “Special” Characters . 8 Table 2: Predefined LATEX 2ε Text-mode Commands . 8 Table 3: LATEX 2ε Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 8 Table 4: AMS Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 9 Table 5: Non-ASCII Letters (Excluding Accented Letters) . 9 Table 6: Letters Used to Typeset African Languages . 9 Table 7: Letters Used to Typeset Vietnamese . 9 Table 8: Punctuation Marks Not Found in OT1 . 9 Table 9: pifont Decorative Punctuation Marks . 10 Table 10: tipa Phonetic Symbols . 10 Table 11: tipx Phonetic Symbols . 11 Table 13: wsuipa Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 14: wasysym Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 15: phonetic Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 16: t4phonet Phonetic Symbols . 13 Table 17: semtrans Transliteration Symbols . 13 Table 18: Text-mode Accents . 13 Table 19: tipa Text-mode Accents . 14 Table 20: extraipa Text-mode Accents . -

Instruction Manual Manuel D'instructions Manual De Instrucciones Bedienungsanleitung Manuale Di Istruzioni

78-8840, 78-8850, 78-8890 MAKSUTOV-CASSEGRAIN WITH REAlVOICE™ OUTPUT AVEC SORTIE REALVOICE™ 78-8831 76MM REFLECTOR CON SALIDA REALVOICE™ MIT REALVOICE™ SPRACHAUSGABE CON USCITA REALVOICE™ INSTRUCTION MANUAL MANUEL D’INSTRUCTIONS MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES BEDIENUNGSANLEITUNG MANUALE DI ISTRUZIONI 78-8846 114MM REFLECTOR Lit.#: 98-0433/04-13 ENGLISH ENJOYING YOUR NEW TELESCOPE 1. You may already be trying to decide what you plan to look at first, once your telescope is setup and aligned. Any bright object in the night sky is a good starting point. One of the favorite starting points in astronomy is the moon. This is an object sure to please any budding astronomer or experienced veteran. When you have developed proficiency at this level, other objects become good targets. Saturn, Mars, Jupiter, and Venus are good second steps to take. 2. The low power eyepiece (the one with the largest number printed on it) is perfect for viewing the full moon, planets, star clusters, nebulae, and even constellations. These should build your foundation. Avoid the temptation to move directly to the highest power. The low power eyepiece will give you a wider field of view, and brighter image—thus making it very easy to find your target object. However, for more detail, try bumping up in magnification to a higher power eyepiece on some of these objects. During calm and crisp nights, the light/dark separation line on the moon (called the “Terminator”) is marvelous at high power. You can see mountains, ridges and craters jump out at you due to the highlights. Similarly, you can move up to higher magnifications on the planets and nebulae. -

Bern Symbols

T H E S Y M B O L S O F B E R N U N I O N C H U R C H R.D.1, LEESPORT, PENNSYSLVANIA By the grace of God, I was able to prepare this booklet as a member of BERN REFORMED CHURCH in the year 1974. I dedicate it to my wife, DOROTHY M. (SEIFRIT) REESER, who has given of her best for the advancement of the Kingdom of God in Bern Reformed and Lutheran Church and also in memory of my wife, Dorothy’s parents, FRANK AND TAMIE SEIFRIT who gave of their best in support of Bern United Church of Christ of the Bern Union Church. EARL H. REESER Note: Typos and minor grammar errors have been corrected. THE SYMBOLS OF BERN UNION CHURCH Earl H. Reeser I heard people say that the stained-glass windows in the Bern Reformed and Lutheran Church of Leesport, R.D.1, along Rt. 183, are the most beautiful they have ever seen. It is with these thoughts in mind that prompted me to undertake my interpretation of the meaning of the symbols as well as other work you see before you, which the building committee saw fit to install in the building of this church. The first church built was exclusively by the Reformed. When this organization was affected, is not definitely known, but the belief is, that it may have been as early as 1739. The earliest baptism is recorded in that year. When the first building was erected, is also not definitely known. -

Identifying Semitic Roots: Machine Learning with Linguistic Constraints

Identifying Semitic Roots: Machine Learning with Linguistic Constraints Ezra Daya∗ University of Haifa Dan Roth∗∗ University of Illinois Shuly Wintner† University of Haifa Words in Semitic languages are formed by combining two morphemes: a root and a pattern. The root consists of consonants only, by default three, and the pattern is a combination of vowels and consonants, with non-consecutive “slots” into which the root consonants are inserted. Identifying the root of a given word is an important task, considered to be an essential part of the morphological analysis of Semitic languages, and information on roots is important for linguistics research as well as for practical applications. We present a machine learning approach, augmented by limited linguistic knowledge, to the problem of identifying the roots of Semitic words. Although programs exist which can extract the root of words in Arabic and Hebrew, they are all dependent on labor-intensive construction of large-scale lexicons which are components of full-scale morphological analyzers. The advantage of our method is an automation of this process, avoiding the bottleneckof having to laboriously list the root and pattern of each lexeme in the language. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of machine learning to this problem, and one of the few attempts to directly address non-concatenative morphology using machine learning. More generally, our results shed light on the problem of combining classifiers under (linguistically motivated) constraints. 1. Introduction The standard account of word-formation processes in Semitic languages describes words as combinations of two morphemes: a root and a pattern.1 The root consists of consonants only, by default three (although longer roots are known), called radicals. -

The-Gospel-Of-Mary.Pdf

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN GOSPEL TEXTS General Editors Christopher Tuckett Andrew Gregory This page intentionally left blank The Gospel of Mary CHRISTOPHER TUCKETT 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Christopher Tuckett, 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services Ltd., Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn, Norfolk ISBN 978–0–19–921213–2 13579108642 Series Preface Recent years have seen a signiWcant increase of interest in non- canonical gospel texts as part of the study of early Christianity. -

Official Journal

THE CITY RECORD. OFFICIAL JOURNAL. VOL XXVI. NEW YORK, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 1898. NUMBER 7,777, DEPARTMENT OF STREET CLEANING. final Disposition of /lfalemal. Cart.86oads. At Barren Island (N.Y. S. U. Co. 734 AtSea ............................................................... I,o79,fi73'/z Report for the Quarter arld Year Ending December 31, 1897 AtNewtown Cieek .......................................................... 262,6O2y4 AtWhale (;reek ............................................................ 750 AtLong Island ...................................... ................ 10,094 DEPARIIIIENT OF STREET CLEANING-CITY OF NEW YORK, I AtWoodbridge Creek ....................................................... 362 ,NEw YORK, October 26, 1898. AtStaten Island ........................................ ................... 525 Hon. ROBERT A. VAN \VYCK, rllayor : AtEllis Island .............................................................. 1,250 SIR--As required by section 1544 of the Charter, I beg to hand you herewith a report of the Sunk at Stanton Street Dump ................................................. 102 business of the Department of Street Cleaning under my predecessor, for the last quarter of the year AtSt. George, Staten Island ..................................... ............ 35,o833. 1897, together with a resume of the business for the entire year. AtFlushing .............................................................. 1,588 The delay in sending this report in has been caused by some accounts of 1897 which were not In lots........... -

As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain

Department of History and Civilization As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain Ana Avalos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, February 2007 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of History and Civilization As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain Ana Avalos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Peter Becker, Johannes-Kepler-Universität Linz Institut für Neuere Geschichte und Zeitgeschichte (Supervisor) Prof. Víctor Navarro Brotons, Istituto de Historia de la Ciencia y Documentación “López Piñero” (External Supervisor) Prof. Antonella Romano, European University Institute Prof. Perla Chinchilla Pawling, Universidad Iberoamericana © 2007, Ana Avalos No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author A Bernardo y Lupita. ‘That which is above is like that which is below and that which is below is like that which is above, to achieve the wonders of the one thing…’ Hermes Trismegistus Contents Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Introduction 6 1. The place of astrology in the history of the Scientific Revolution 7 2. The place of astrology in the history of the Inquisition 13 3. Astrology and the Inquisition in seventeenth-century New Spain 17 Chapter 1. Early Modern Astrology: a Question of Discipline? 24 1.1. The astrological tradition 27 1.2. Astrological practice 32 1.3. Astrology and medicine in the New World 41 1.4.