“The Images of Atlantic Canada Found in Recent Roots/Traditional Music: What Is It Like ‘Down There’?”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Bibiical Drama by Chester N. Scoville a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with The

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English BibIical Drama by Chester N. Scoville A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto O Copyright by Chester N. Scoville (2000) National Library Bibiiotheque nationale l*l ,,na& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rwW~gtm OttawaON KlAûîU4 OtÈewaûN K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2000 Department of English, University of Toronto The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Biblical Dnma by Chester N. Scovilie Much past criticism of character in Middle English drarna has fallen into one of two rougtily defined positions: either that early drama was to be valued as an example of burgeoning realism as dernonstrated by its villains and rascals, or that it was didactic and stylized, meant primarily to teach doctrine to the faithfùl. -

Sexual Trauma and Abuse: Restorative and Transformative Possibilities?

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Sexual Trauma and Abuse: Restorative and Transformative Possibilities? Authors(s) Keenan, Marie Publication date 2014-11-27 Publisher University College Dublin. School of Applied Social Science Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/6247 Downloaded 2021-09-26T18:57:06Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Sexual Trauma and Abuse: Restorative and Transformative Possibilities? A Collaborative Study on the potential of Restorative Justice in Sexual Crime in Ireland DR. MARIE KEENAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN This report is based on the results of a collaborative study between Facing Forward, Ms Bernadette Fahy and Dr Marie Keenan. The Research Assistant Interns who helped with data analysis [supported by the Government JobBridge Scheme] also made a significant contribution to this research and sincere thanks are due to Cian O’ Concubhair, Olive Lyons, Graham Loftus, Martin Mulrennan, Hannah Gilmartin, Andrea Kennedy, Patrice Reilly and Chris Kelly. Cian O’Concubhair’s written work on accountability mechanisms in legal systems enormously enhanced particular sections of this report. Thanks are due to UCD’s Geary Institute for providing office accommodation for the Research Assistant Interns during -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Symphony Nova Scotia Fonds (MS-5-14)

Dalhousie University Archives Finding Aid - Symphony Nova Scotia fonds (MS-5-14) Generated by the Archives Catalogue and Online Collections on January 24, 2017 Dalhousie University Archives 6225 University Avenue, 5th Floor, Killam Memorial Library Halifax Nova Scotia Canada B3H 4R2 Telephone: 902-494-3615 Email: [email protected] http://dal.ca/archives http://findingaids.library.dal.ca/symphony-nova-scotia-fonds Symphony Nova Scotia fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 4 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Collection holdings .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Administration and finance records of Symphony Nova Scotia (1984-2003) ............................................. 7 Budgets records of Symphony -

Great Big Sea's Sean Mccann, an Intimate

FROM: CHILLIWACK ARTS & CULTURAL CENTRE SOCIETY 9201 Corbould Street, Chilliwack BC V2P 4A6 Contact: Ann Goudswaard, Marketing Manager 604.392.8000, ext.103 [email protected] www.chilliwackculturalcentre.com February 16, 2018 High Resolution photo: Séan Mccann.jpg Description: Séan Mccann’s love for Newfoundland and Labrador folk songs shot him to international fame as a founding member of the renowned group Great Big Sea. After twenty years with the band, Séan decided to leave them and start over, in an attempt to find his own peace, love, and happiness. Photo Credit: N/A FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Great Big Sea’s Sean McCann, An Intimate Evening. CHILLIWACK, BC — A rare opportunity to experience one of the East Coast’s most well-loved singers, songwriters and storytellers is coming up this spring, when a founding member of a Canadian folk treasure embarks on a voyage to Chilliwack. On March 3, 2018, An Intimate Evening with Séan McCann will present the Newfoundland and Labrador songsmith and founding member of Great Big Sea, Séan McCann, in a uniquely up-close-and-personal performance that captures the energy and honesty that has come to define McCann’s solo career. Whether a fan old or new, of soft-spoken ballads or rousing folk singalongs, this show is sure to speak to your heart and leave you uplifted and inspired. Beginning almost 30 years ago in St John’s, Newfoundland, Séan McCann’s career has been a storied tale. From international acclaim with Great Big Sea and a life-changing decision to leave the band to concentrate on his solo career, to battling alcoholism and revealing long-harboured secrets of abuse on a journey to find healing and happiness, McCann has weathered both the calm and the storm. -

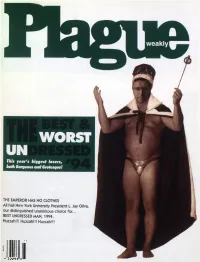

THE EMPEROR HAS HO CLOTHES All Hail New

fi % ST This year's biggesi losers, both Gorgeous and Grotesque! THE EMPEROR HAS HO CLOTHES All hail New York University President L. Jay Oliva, our distinguished unanimous choice for... BEST UNDRESSED MAN, 1994. Huzzah!!! HuzzahN! Huzzah!!! JSJ/O B u M b l E F u c k A i r Liines W e 'U TAkE you WHERE INO ONE ELSE WANTS TO GO. GRAND HAVEN Like sunny Grand Haven, M ichigan, hom e of the world's largest musical fountain! Lucky for you, as a tourist with Bum blefuck Airlines, you can not only witness the quaint rituals of rural existence, you can leave. C om e along on one of our pre-packaged tours, or go your own way. Prices start from $699 round trip, and only $15 one-way. The depressed prices in the local m om & pop stores will put you in hog heaven. The exchange rate is phenom enal: one New York City dollar is worth $1.84 in Grand Haven! In layman's terms this means that where in NY you can pur chase a small french fries, in CH you can purchase a small franchise. It's just like visiting a Third World nation, except here they've got a trolley. Tour the thriving dow ntow n metropolis and m eet som e of the local folk wandering around. Plenty of free parking! Centralia ranks am ong our most popular destinations! Our weekend getaway prices start at $499 round trip. This includes airfare, rental car courtesy of Corwin Insurance, and two nights accomodations at Casa del Zim m erm an on stately Seminary Hill, a m ost aptly nam ed locale. -

The Rankin Family Live at the Red Robinson Show Theatre

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OCTOBER 11, 2011 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS THE RANKIN FAMILY LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 27 Coquitlam, BC – It was in 1989 when Cape Breton siblings – Raylene, John Morris, Jimmy, Cookie and Heather Rankin – began touring together professionally when just a year later with the independent release of their second recording, Fare Thee Well Love, they were signed to Capitol/EMI Music. After the label re-released the album in 1992, it quickly went on to become a platinum seller with the title track finding its way to the Disney film, Into the West. The following year, they released North Country which featured the popular title track along with “Borders and Time” resulting in another-multi platinum success for The Rankin Family. Their music crossed over many musical styles earning them a fast growing following as well as industry accolades that included six Juno Awards and fifteen East Coast Music Awards. Both Grey Dusk of Eve and Endless Seasons were released in 1995 followed by Heather, Cookie and Raylene’s best-selling Christmas album, Do You Hear What I Hear. In 1998, the group released their final album together … aptly titled Uprooted. The following year, they decided to go their separate ways … each pursuing their own interests and musical projects. It wasn’t until eight years later that in 2007, they released their Reunion album and the family soon set out on a cross-Canada tour with niece Molly Rankin – daughter of the late John Morris – completing the line-up. It was as though no time had passed … night after night, audiences welcomed them back into the fold. -

Steve Angelentertainment

steve angel ENTERTAINMENT The Finest in Live Music steve angel ENTERTAINMENT The Finest in Live Music From the casino lounges of Las Vegas, the beach-side resorts of the Florida coast, and the exciting nightclubs of Amsterdam…Steve Angel has entertained music lovers from all walks of life throughout North America and Europe. After living and performing abroad for many years, Steve has returned to Toronto, Canada where he continues his fine blend of musical taste for all listeners alike. One of Southern Ontario’s premiere entertainers, Steve Angel entertainment performs a wide selection of music including popular hits from the 1920′s to today’s top 40. A multi-talented individual, he sings (in 7 languages), plays the trumpet, guitar, percussion and the accordion! Upon receiving his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from York University in Toronto, Steve decided to pursue his career as a professional musical entertainer. Playing a schedule of well over 200 shows annually from solo to full ensemble, Steve Angel’s charm and spontaneity that he brings to the stage has established a reputation that is in a class of its own. Hip, hot, and full of high-driving energy, his musical voodoo will invade your spirit and keep you dancing all night long! Steve Angel Entertainment is available for concert, wedding, corporate, nightclub and special events. Phone 905.399.2147 (CAN) or 813.504.1265 (USA) Email [email protected] www.steveangelentertainment.com steve angel ENTERTAINMENT The Finest in Live Music Guarantee Professional Well-known with -

Popular Magazines, Or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 24 Issue 1 Russian Culture of the 1990s Article 3 1-1-2000 Style and S(t)imulation: Popular Magazines, or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia Helena Goscilo University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Goscilo, Helena (2000) "Style and S(t)imulation: Popular Magazines, or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1474 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Style and S(t)imulation: Popular Magazines, or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia Abstract The new Postsoviet genre of the glossy magazine that inundated bookstalls and kiosks in Russia's urban centers served as both an advertisement for a life of luxury and an advice column on chic style. Conventionalized signs of affluence, models of beauty, "educational" articles on topics ranging from the history and significance of ties ot correct behavior at a first-class estaurr ant filled the pages of magazines intended to provide an accelerated course in etiquette, appearance, and appurtenances for Russia's newly wealthy. The lessons in spending, demeanor, and taste emphasized moneyed visibility. -

Searchable-Printable PDF Index by Title

BS1: Brenda Stubbert’s Collection of Fiddle Tunes Alexa Morrison’s ............................................ jig ............ LC ...... #280 .. 108 BS2: Brenda Stubbert: The Second Collection Alexander Deas' Jig ...................................... jig ......... CBSC .... #314 .. 117 CBFC: The Cape Breton Fiddlers Collection Alexander Glen ........................................... march ...... CBHC ..... #50 .... 26 CBHC: The Cape Breton Highland Collection Alexander Laidlaw Wood .............................. reel ........ CBHC ... #100 .... 53 CBSC: The Cape Breton Scottish Collection Alexander MacDonald .................................. reel .......... JH2 ....... #30 .... 13 JH1: Jerry Holland’s Collection of Fiddle Tunes Alexander William MacDonnell ...................... jig ........... JH2 ..... #287 .. 103 JH2: Jerry Holland: The Second Collection Alexander William MacDonnell’s .................. reel .......... JH1 ......... #9 ...... 4 LC: The Lighthouse Collection Alf’s Love for Carol McConnell ..................... reel .......... JH2 ....... #85 .... 34 WFC: Winston Fitzgerald: A Collection of Fiddle Tunes Alice MacEachern ........................................ reel ........... LC ........ #84 .... 33 Alice Robertson ............................................ reel ........ CBHC ....... #2 ..... iv italics indicate alternate titles Alick C. McGregor’s ...................................... reel .......... BS2 ......... #4 ...... 2 All My Friends ............................................... reel .......... JH1 -

Daly Berman 1 Amanda Elaine Daly Berman Boston University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Musicology And

Daly Berman 1 Amanda Elaine Daly Berman Boston University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Musicology and Ethnomusicology Repression to Reification: Remembering and Revitalizing the Cape Breton Musical Diaspora in the Celtic Commonwealth INTRODUCTION Cape Breton Island, the northeast island of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, has long had a strong connection with New England, and the Boston area in particular, due to its maritime location and relative geographic proximity. At its peak in the mid-20th century, the Boston Cape Breton community is estimated to have numbered close to 100,000 members. However, as Sean Smith writes in the June 3, 2010 issue of the Boston Irish Reporter, Greater Boston’s Cape Breton community is undergoing a transition, with the graying of the generation that played such a major role during the 1950s and 1960s in establishing this area as a legendary outpost for music and dance of the Canadian Maritimes. Subsequent generations of Cape Bretoners have simply not come down to the so-called “Boston states” on the same scale, according to the elders; what’s more, they add, the overall commitment to traditional music and dance hasn’t been as strong as in past generations.1 Further, he notes that it is “non-Cape Bretoners [e.g., members of other Maritime communities, non-Cape Breton Bostonians] who seem to make up more of the attendance at these monthly dances” held at the Canadian-American Club (also known as the Cape Breton Gaelic Club) in Watertown, Massachusetts. The club serves as a gathering site for area members of the Cape Breton and the greater Maritime diaspora, offering a monthly Cape Breton Gaelic Club Ceilidh and weekly Maritime open mic sessions. -

Volume 61 No. 10 - ($2.80 Plus .20 GST) 2 - RPM - Monday April 10 1995 the System

$3.00Volume($2.80 61 plus No. .20 GST) 10 - Introduction2 - RPM - Monday April of10 1995 BDS raises eyebrows at radio the system."There All isn't anyone any actual will befee paying to be set for up is with the marketsnationwidemusicBroadcast trackingBDS throughout Data in has Canada Systemssystem, been Canada, this conducting is(BDS), month. set includingto thebegin tests computerized inoperating Toronto, various PatternGreggVancouver.Hamilton, Miller, Recognition.According Winnipeg, the process to Essentially, BDS Calgary,is based regional BDSon Edmonton a sales systemtakes director a called piece and anddiscussion."peraccess 440song toBDS television the basis, information.currently butoutlets monitorsthat's Wein the normallyobviously 500largest radio chargemarkets stationsup onfor in a Halifax,operatingHamiltonCOVER Montreal,nationallyand STORY London. any Ottawa, The day systemnow, Toronto, with will monitors beLondon, up and in Canada.computerThosemakesof music a `fingerprints' digital supplied monitors fingerprint to it in areby those theout then recordof 10 thatdownloaded markets piececompanies of acrossmusic. into and shoutingtheirlaunchedthe US. system, WhileThe hoorayin the monitoring BDS not UK. at everyonetheclaims impending system a 99% is wasstandingefficiency arrival also ofrecently uprate BDS. and for ContraryofSouth the to closet Mountainwhat some swinging may have comes believed, outSouth to.stereofingerprintstwo So purposes: we'retuners,According in, listening One,one and tofor two,they Miller, toeach they'reacteach stationas "Those radioa hooked library we'restationmonitors upto listening storeto in actual serveeach the honestly.thatstabRadio stationsat programmers,theirDanny integrity, might Kingsbury, not for and beone, that reporting vice-presidentfeel it hints the everythingsystem at the ideais of a ofhomeBC.Mountain the This ofbestThe what small (pop.country five many town, 365)-piece bands are is just beginningbandin in Ontario,south Canada.