The Effects of Austin's Urban Branding on Its Local Musicians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Is Austin Still Austin?

1 IS AUSTIN STILL AUSTIN? A CULTURAL ANALYSIS THROUGH SOUND John Stevens (TC 660H or TC 359T) Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 13, 2020 __________________________________________ Thomas Palaima Department of Classics Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Richard Brennes Athletics Second Reader 2 Abstract Author: John Stevens Title: Is Austin Still Austin? A Cultural Analysis Through Sound Supervisors: Thomas Palaima, Ph. D and Richard Brennes For the second half of the 20th century, Austin, Texas was defined by its culture and unique personality. The traits that defined the city ushered in a progressive community that was seldom found in the South. In the 1960s, much of the new and young demographic chose music as the medium to share ideas and find community. The following decades saw Austin become a mecca for live music. Austin’s changing culture became defined by the music heard in the plethora of music venues that graced the city streets. As the city recruited technology companies and developed its downtown, live music suffered. People from all over the world have moved to Austin, in part because of the unique culture and live music. The mass-migration these individuals took part in led to the downfall of the music industry in Austin. This thesis will explore the rise of music in Austin, its direct ties with culture, and the eventual loss of culture. I aim for the reader to finish this thesis and think about what direction we want the city to go in. 3 Acknowledgments Thank you to my advisor Professor Thomas Palaima and second-reader Richard Brennes for the support and valuable contributions to my research. -

Austin, Texas Marie Le Guen

Special Issue Urbanities, Vol. 7 · No 2 · November 2017 The Dreams and Nightmares of City Development © 2017 Urbanities Urban Transformations, Ideologies of Planning and Actors’ Interplay in a Booming City — Austin, Texas Marie Le Guen (University Lumière Lyon 2) [email protected] The city of Austin, state capital of Texas, has been experiencing an impressive process of metropolization, while growing very quickly, since the end of the twentieth century. Its successful adaptation to the economy’s global trends and the growth it brings about are destabilizing Austin’s planning system, which is already very constrained in Texas’ most conservative political framework. Increasing tensions between established groups of actors and the emergence of newer ones prompt several changes in the professional and civic culture of the various actors involved in the urban planning field. These changes arise from the fact that these groups of actors are confronted with urban mutations never seen before. The ideology of planning, its meanings and its practices, are also evolving in this economic and social context, allowing for a larger citizens’ participation and putting sustainability on the political agenda. Keywords: Urban planning, public participation, democracy, sustainable development. Introduction Since the end of the twentieth century, Austin, the state capital of Texas, has experienced tremendous population and economic growth, as well as a diversification of its urban functions, which can be condensed into the process called metropolization. Exhibited as a ‘creative city’ (Florida 2002), Austin embodies a successful adaptation to the global trends. The quick growth, partly resulting from this adaptation, is fuelling urban sprawl, causing environmental degradation, and destabilizing its planning system. -

Music Industry Report 2020 Includes the Work of Talented Student Interns Who Went Through a Competitive Selection Process to Become a Part of the Research Team

2O2O THE RESEARCH TEAM This study is a product of the collaboration and vision of multiple people. Led by researchers from the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and Exploration Group: Joanna McCall Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Barrett Smith Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Jacob Wunderlich Director, Business Development and Applied Research, Exploration Group The Music Industry Report 2020 includes the work of talented student interns who went through a competitive selection process to become a part of the research team: Alexander Baynum Shruthi Kumar Belmont University DePaul University Kate Cosentino Isabel Smith Belmont University Elon University Patrick Croke University of Virginia In addition, Aaron Davis of Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach of the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce contributed invaluable input and analysis. Cluster Analysis and Economic Impact Analysis were conducted by Alexander Baynum and Rupa DeLoach. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 - 6 Letter of Intent Aaron Davis, Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach, The Research Center 7 - 23 Executive Summary 25 - 27 Introduction 29 - 34 How the Music Industry Works Creator’s Side Listener’s Side 36 - 78 Facets of the Music Industry Today Traditional Small Business Models, Startups, Venture Capitalism Software, Technology and New Media Collective Management Organizations Songwriters, Recording Artists, Music Publishers and Record Labels Brick and Mortar Retail Storefronts Digital Streaming Platforms Non-interactive -

Copyright by Krishnan Vasudevan 2017

Copyright by Krishnan Vasudevan 2017 The Dissertation Committee for Krishnan Vasudevan Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Black Media Producers of Austin, Texas: Critical Media Production and Design as Citizenship Committee: Mary Angela Bock, Supervisor Wenhong Chen Donna DeCesare Robert Jensen S. Craig Watkins Black Media Producers of Austin, Texas: Critical Media Production and Design as Active Citizenship by Krishnan Vasudevan Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2017 Dedication This is dedicated to all of the storytellers, social workers and teachers who fight for equality. Please never stop. Acknowledgements Throughout my life, strong women have guided my path and this process was no different. I could not have completed this process without the enduring support of my brilliant and beautiful wife, Mairead, who always believes in me. I am tremendously grateful to my dissertation chair Professor Mary Angela Bock for seeing value in the hodgepodge of disparate ideas I originally presented to her. My selfless and wise sisters, Lalitha and Veena, not only laid out the road map for me to base my own journey but also were always there to listen. I am so thankful for the unconditional love of my mother and father. I want to acknowledge my supportive dissertation committee who allowed and encouraged me to think differently. Finally but perhaps most importantly, this project could not have existed had it not been for the participation of nine tremendously talented visual artists. -

Librarian in the Underground What Academic Libraries Can Learn from DIY Culture

Solomon Blaylock and Declan Ryan Librarian in the underground What academic libraries can learn from DIY culture See yourself as the pilot of an elabo- crisscrossing North America every day. We’ve rate spacecraft in unfamiliar territory. walked in both pairs of shoes, and we’re con- If you freeze, tense up, refuse to look vinced. We can sum it up in three letters: DIY. at what is in front of you, you will crack up the ship. On the other hand, So what is DIY? DO IT YOURSELF! credulity and uncritical receptivity are Unless you’ve got a rich uncle or write the almost as dangerous. kind of music that’s going to end up play- —William S. Burroughs, Ah Pook Is Here ing in a Gap changing room you’re going to need to bust your hump as a musician. You cademic library professionals are now don’t play a few club gigs, get discovered Ain uncharted territory. We’re hurtling and signed, and ease into a life of destroying through unfamiliar, rapidly shifting land- expensive hotel rooms. You’re going to haul scapes. Information storage and retrieval, your own amps, replace your own strings, scholarly publishing, information literacy: drive your own vehicle into the ground, eat everything’s changing on a daily basis. Get $1 meals, sweat it out under broken lights hung up on any one thing, and you’re already at clubs with all of three people in the au- working in the past. Allow yourself to be dience, play on the same grimy basement overwhelmed and you’re paralyzed. -

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982 Alan Schaefer The opening of the Vulcan Gas Company in 1967 marked a significant turning point in the history of music, art, and underground culture in Austin, Texas. Modeled after the psychedelic ballrooms of San Francisco, the Vulcan Gas Company presented the best of local and national psychedelic rock and roll as well as the kings and queens of the blues. The primary 46 medium for advertising performances at the 47 venue was the poster, though these posters were not simple examples of commercial art with stock publicity photos and redundant designs. The Vulcan Gas Company posters — a radical body of work drawing from psychedelia, surrealism, art nouveau, old west motifs, and portraiture — established a blueprint for the modern concert poster and helped articulate the visual language of Austin’s emerging underground scenes. The Vulcan Gas Company closed its doors in the spring of 1970, but a new decade witnessed the rapid development of Austin’s music scene and the posters that promoted it. Austin’s music poster artists offered a visual narrative of the music and culture of the city, and a substantial collection of these posters has found a home at the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University. The Wittliff Collections presented Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982 in its gallery in the Alkek Library in 2015. The exhibition was curated by Katie Salzmann, lead archivist at the Wittliff Collections, and Alan Schaefer, a lecturer in the Department of English Jim Franklin. New Atlantis, Lavender Hill Express, Texas Pacific, Eternal Life Corp., and Georgetown Medical Band. -

Haam Annual Report 2013

PHOTO BY BRENDA LADD PHOTOGRAPHY HAAM ANNUAL REPORT 2013 www.myhaam.org Dear Friends of HAAM: The year 2013 brought many changes to the health care landscape in our nation, our community and to the Health Alliance for Austin Musicians (HAAM). But through it all, HAAM’s core values and mission remained rock solid. We love Austin. We love live music. And we love what HAAM does for Austin’s musicians. Two major changes affected HAAM in 2013. First, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) began to take effect—opening new doors for many HAAM members to obtain health insurance. Although some people thought that the ACA might reduce the need for HAAM, nothing could be further from the truth. Because Texas did not follow many other states and expand its Medicaid eligibility, more than 60% of current HAAM members still need HAAM to access affordable health care. Additionally, the ACA does not usually provide the dental, vision, hearing and other health care services that are currently available to HAAM members. The second major change for HAAM in 2013 was the departure of our much loved, longtime executive director, Carolyn Schwarz, who deftly guided the organization for eight years. We wish her well and welcome Reenie Collins to our team as executive director. A native Austinite with deep roots in the health care and non-profit community, Reenie is passionate about HAAM and its mission. Reenie has a long-standing history with the HAAM family and actually worked as a health care consultant to our founder Robin Shivers in 2005 when HAAM was being formed. -

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas BY Joshua Long 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Geography __________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson __________________________________ Dr. Jane Gibson __________________________________ Dr. Brent Metz __________________________________ Dr. J. Christopher Brown __________________________________ Dr. Shannon O’Lear Date Defended: June 5, 2008. The Dissertation Committee for Joshua Long certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas ___________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson Date Approved: June 10, 2008 ii Acknowledgments This page does not begin to represent the number of people who helped with this dissertation, but there are a few who must be recognized for their contributions. Red, this dissertation might have never materialized if you hadn’t answered a random email from a KU graduate student. Thank you for all your help and continuing advice. Eddie, you revealed pieces of Austin that I had only read about in books. Thank you. Betty, thank you for providing such a fair-minded perspective on city planning in Austin. It is easy to see why so many Austinites respect you. Richard, thank you for answering all my emails. Seriously, when do you sleep? Ricky, thanks for providing a great place to crash and for being a great guide. Mycha, thanks for all the insider info and for introducing me to RARE and Mean-Eyed Chris. -

Knowledge Workers: a Psychological Approach to Living and Working

Knowledge Workers A Psychological Approach to Living and Working Stephanie Carlson Abstract Th is project intends to develop a live-work building for knowledge workers through the application of the principles of environmental psychology. Th e site is located in downtown Austin, Texas—a technology hub with an active urban environment attractive to professionals seeking the fl exibility and bal- ance knowledge work provides. Knowledge workers perform symbol work that is neither temporally nor physically bound; however, they still operate within existing spatial constructs that do not address their unique living and working needs. Environmental psychology research can begin to suggest architectural solutions to the physical and psychological issues faced by knowledge workers. Th e application of this research will be determined through the examination of the tension between living and working spaces, as well as the relationship be- tween public and private. Th e slow process of drawing by hand brings together the mental and the kinesthetic into a physical form, refl ecting an architectural process which attempts to bring together psychology and the physicality of space into a cohesive architecture which supports the work and well-being of knowledge workers. Contents i Introduction 42 Restoration 48 Place I Waves of Change IV Analysis 1 Introduction 3 Th e Agricultural Age 53 Introduction 5 Th e Industrial Age 54 Weird City 9 Th e Information Age 59 Site and Program II Blurred Boundaries V Conclusion 13 Introduction 69 Summary 14 Blurring Live-Work 20 Knowledge Work 71 Notes 77 Figures III Supportive Spaces 81 References 23 Introduction 25 Evidence-Based Design 87 Appendix: Design 31 Stimulation 35 Control Introduction One machine can do the work of fi fty ordinary men. -

Live Venue Sound System Installation

CASE STUDIES Live Venue Installations Unite Your Audience The Martin Audio Experience LIVE VENUE INSTALLATIONS Martin Audio At Martin Audio we believe that uniting audiences with modelling and software engineering, to deliver dynamic, exciting sound creates shared memories that sear into the full-frequency sound right across the audience. consciousness delivering more successful tours, events and repeatedly packed venues. With over forty years of live sound and installation expertise to our name, Martin Audio offers a wide range of premium We achieve this by an obsessive attention to detail on professional loudspeakers so customers can be assured the professional sound system’s acoustic performance, of selecting the right system for their chosen application, frequently challenging convention and involving a whether it’s a small scale installation or a festival for over sophisticated mix of design, research, mathematical 150,000 people. Live Venue Installations With our heritage in live production it’s no surprise that this has transferred into the realms of permanent audio installation within live venues. More often than not, live venues are combined with bar and club areas so our portfolio offering has frequently meant and integrated system design approach. As with many other applications, our solutions focus upon appropriate sound level performance, coverage, consistency and control to unite audiences night after night. 2 LIVE VENUE INSTALLATIONS Cabo Wabo Cantina Upgrades With Martin Audio WPC Cabo Wabo Cantina Cabo San Lucas, MX––Sammy -

The 35 Best Folk Music Venues in the U.S

The 35 Best Folk Music Venues in the U.S. Tweet Like 2.9K Share Save (https://www.reddit.com/submit) Click a state to view its venue(s) Although folk music may have hit its zenith in the 1960s, the genre still thrives today, along with a dedicated base of fans. It lives in music venues on each coast as well as hundreds of places in between. ARIZONA Folk music is still with us because it connects the listener, and the artist, to our cultural heritage. The tunes and lyrics CALIFORNIA describe who we are and where we came from. COLORADO Below is a list of the top 35 folk venues in the United States. We've listed the venues alphabetically by state. CONNECTICUT These 35 venues are not necessarily dedicated to folk music, but they are places where folk music indeed thrives. They ILLINOIS are also elite live music venues with superb acoustics, sightlines, and atmospheres, all qualities needed to make our list. MARYLAND The deciding factor, however, was enthusiasm. The following 35 venues exhibit a fervor for folk music that is almost MASSACHUSETTS palatable. MICHIGAN The people behind these venues love what they do and they love folk music. And, as you'll soon read, many of these NEW YORK venues are run by volunteers. NORTH CAROLINA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA RHODE ISLAND Arizona TEXAS VIRGINIA The Lost Leaf Bar & Gallery 914 North 5th Street Phoenix, AZ The Lost Leaf Bar & Gallery is an amazing venue for any type of show, especially folk music. For one, all their shows are free. -

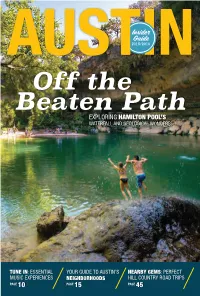

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected].