Encounter with Zen Books by Lucien Stryk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Square in Oxford Since 1979. U.S

Dear READER, Service and Gratitude It is not possible to express sufficiently how thankful we at Square Books have been, and remain, for the amazing support so many of you have shown to this bookstore—for forty years, but especially now. Nor can I adequately thank the loyal, smart, devoted booksellers here who have helped us take safe steps through this unprecedented difficulty, and continue to do so, until we find our way to the other side. All have shown strength, resourcefulness, resilience, and skill that maybe even they themselves did not know they possessed. We are hearing stories from many of our far-flung independent bookstore cohorts as well as other local businesses, where, in this community, there has long been—before Amazon, before Sears—a shared knowledge regarding the importance of supporting local places and local people. My mother made it very clear to me in my early teens why we shopped at Mr. Levy’s Jitney Jungle—where Paul James, Patty Lampkin, Richard Miller, Wall Doxey, and Alice Blinder all worked. Square Books is where Slade Lewis, Sid Albritton, Andrew Pearcy, Jesse Bassett, Jill Moore, Dani Buckingham, Paul Fyke, Jude Burke-Lewis, Lyn Roberts, Turner Byrd, Lisa Howorth, Sami Thomason, Bill Cusumano, Cody Morrison, Andrew Frieman, Katelyn O’Brien, Beckett Howorth, Cam Hudson, Morgan McComb, Molly Neff, Ted O’Brien, Gunnar Ohberg, Kathy Neff, Al Morse, Rachel Tibbs, Camille White, Sasha Tropp, Zeke Yarbrough, and I all work. And Square Books is where I hope we all continue to work when we’ve found our path home-free. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

N° Artiste Titre Formatdate Modiftaille 14152 Paul Revere & the Raiders Hungry Kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben

N° Artiste Titre FormatDate modifTaille 14152 Paul Revere & The Raiders Hungry kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben Verliefd Op Jou kar 2004 48 860 14154 Paul Simon A Hazy Shade Of Winter kar 1995 18 008 14155 Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard kar 2001 41 290 14156 You Can Call Me Al kar 1997 83 142 14157 You Can Call Me Al mid 2011 24 148 14158 Paul Stookey I Dig Rock And Roll Music kar 2001 33 078 14159 The Wedding Song kar 2001 24 169 14160 Paul Weller Remember How We Started kar 2000 33 912 14161 Paul Young Come Back And Stay kar 2001 51 343 14162 Every Time You Go Away mid 2011 48 081 14163 Everytime You Go Away (2) kar 1998 50 169 14164 Everytime You Go Away kar 1996 41 586 14165 Hope In A Hopeless World kar 1998 60 548 14166 Love Is In The Air kar 1996 49 410 14167 What Becomes Of The Broken Hearted kar 2001 37 672 14168 Wherever I Lay My Hat (That's My Home) kar 1999 40 481 14169 Paula Abdul Blowing Kisses In The Wind kar 2011 46 676 14170 Blowing Kisses In The Wind mid 2011 42 329 14171 Forever Your Girl mid 2011 30 756 14172 Opposites Attract mid 2011 64 682 14173 Rush Rush mid 2011 26 932 14174 Straight Up kar 1994 21 499 14175 Straight Up mid 2011 17 641 14176 Vibeology mid 2011 86 966 14177 Paula Cole Where Have All The Cowboys Gone kar 1998 50 961 14178 Pavarotti Carreras Domingo You'll Never Walk Alone kar 2000 18 439 14179 PD3 Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is kar 1998 45 496 14180 Peaches Presidents Of The USA kar 2001 33 268 14181 Pearl Jam Alive mid 2007 71 994 14182 Animal mid 2007 17 607 14183 Better -

Jim Harrison “A Natural History of Some Poems” JIM HARRISON an INTERVIEW by Allen Morris Jones

The sense of play that a poet needs to make language an ally — often thought of as congenital insincerity by the public—provides the at least momentary pleasure of creation; the sense of having a foothold, if not full membership, in a guild as old as man. The child who carves a tombstone or rock out a bar of soap knows some of this pleasure. —Jim Harrison “A Natural History of Some Poems” JIM HARRISON AN INTERVIEW by Allen Morris Jones t’s a weakness and I can’t get rid of it. How I keep wanting to meet the writers I admire. When he’s in Montana, the poet and novelist Jim Harrison does most of his work in a shed behind his refurbished farmhouse. The house Iitself is tastefully done up in arts and crafts, arrangements of hardwoods and mirrors and original art; his writing space, however, could have come from impoverished Mexico, Argentina, the Balkans. Some mountain village still ten years away from electricity. There’s a sleeping cot (quilts piled up in a wad) and a good-sized desk. A corkboard of photos and shelves full of personal totems. Little else. It’s the room of a writer leery of all distraction save memory. On a Saturday morning in early June, he was working in a raveling, wheat- yellow t-shirt and black sweat pants. Belly in his lap and a legal pad on his desk, the pages folded back. “I’ve never used a computer, even a typewriter. I have a problem with electricity.” This was in the Paradise Valley, south of Livingston. -

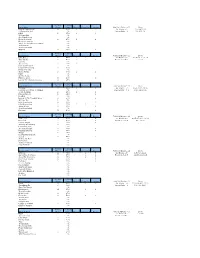

Up to Here # Times Played % Shows Played Opened Closed Set Encore

# Times % Shows Up To Here Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Blow at High Dough 9 60% 2 3 Set Blocks = 6 1,5,7,9,12,14 I'll Believe In You 0% Encore Sets = 5 2,6,8,11,15 NOIS 10 67% 1 4 38 Years Old 0% She Didn't Know 0% Boots Or Hearts 10 67% 2 4 Everytime You Go 0% When The Weight Comes Down 0% Trickle Down 0% Another Midnight 0% Opiated 8 53% 1 2 # Times % Shows Road Apples Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Little Bones 8 53% 1 1 Set Blocks = 8 1,2,4,6,8,10,12,15 Twist My Arm 8 53% 1 2 1 Encore Sets = 3 3,9,13 Cordelia 0% The Luxury 5 33% 1 Born In The Water 0% Long Time Running 4 27% Bring It All Back 0% Three Pistols 6 40% 1 1 Fight 0% On The Verge 0% Fiddler's Green 6 40% 3 Last Of The Unplucked Gems 4 27% # Times % Shows Fully Completely Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Courage 10 67% 2 4 Set Blocks = 7 3,5,8,10,11,13,15 Looking For A Place To Happen 0% Encore Sets = 6.1 1,2,4,7,9,14,15 100th Meridian 10 67% 2 3 Pigeon Camera 2 13% 1 Lionized 0% Locked In The Trunk Of A Car 3 20% 2 We'll Go Too 1 7% Fully Completely 4 27% 3 Fifty Mission Cap 5 33% 1 1 Wheat Kings 8 53% 4 The Wherewithal 0% Eldorado 3 20% 1 # Times % Shows Day For Night Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Grace, Too 13 87% 1 4 Set Blocks = 9 2,3,5,6,7,9,11,13,14 Daredevil 7 47% 1 Encore Sets = 4 4,10,12,15 Greasy Jungle 5 33% 1 Yawning Or Snarling 2 13% Fire In The Hole 0% So Hard Done By 7 47% 1 Nautical Disaster 4 27% 2 Thugs 2 13% Inevitability Of Death 0% Scared 7 47% 2 An Inch An Hour 0% Emergency 0% Titanic Terrarium 0% Impossibilium 0% # Times % Shows Trouble At The Henhouse Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Giftshop 11 73% 1 5 Set Blocks = 6 3,5,7,10,12,14 Springtime In Vienna 7 47% 1 1 Encore Sets = 7 1,4,6,8,11,13,15 Ahead By A Century 13 87% 2 7 Don't Wake Daddy 4 27% 1 Flamenco 5 33% 2 700 Ft. -

Download Spring 2017

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Spring 2017 GROVE ATLANTIC 154 West 14th Street, 12 FL, New York, New York 10011 ATLANTIC MONTHLY PRESS Hardcovers AVAILABLE IN MARCH A collection of essays from “the Henry Miller of food writing” (Wall Street Journal)—beloved New York Times bestselling writer Jim Harrison A Really Big Lunch Meditations on Food and Life from the Roving Gourmand Jim Harrison With an introduction by Mario Batali MARKETING “[A] culinary combo plate of Hunter S. Thompson, Ernest Hemingway, Julian A Really Big Lunch will be published on the Schnabel, and Sam Peckinpah . Harrison writes with enough force to make one-year anniversary of Harrison’s death your knees buckle.” —Jane and Michael Stern, New York Times Book Review on The Raw and the Cooked There was an enormous outpouring of grief and recognition of Harrison’s work at the ew York Times bestselling author Jim Harrison was one of this coun- time of his passing in March 2016 try’s most beloved writers, a muscular, brilliantly economic stylist Harrison’s last book, The Ancient Minstrel, Nwith a salty wisdom. He also wrote some of the best essays on food was a New York Times and national around, earning praise as “the poet laureate of appetite” (Dallas Morning bestseller, as well as an Amazon Editors’ News). A Really Big Lunch, to be published on the one-year anniversary of Best Book of the Month. It garnered strong Harrison’s death, collects many of his food pieces for the first time—and taps reviews from the New York Times Book into his larger-than-life appetite with wit and verve. -

Hugh Padgham Discography

JDManagement.com 914.777.7677 Hugh Padgham - Discography updated 09.01.13 P=Produce / E=Engineer / M=Mix / RM=Remix GRAMMYS (4) MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT / NETWORK Sting Ten Summoner's Tales E/M/P A&M Best Engineered Album Phil Collins "Another Day In Paradise" E/M/P Atlantic Record Of The Year Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Album Of The Year Hugh Padgham and Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Producer Of The Year ARTIST ALBUM CREDIT LABEL 2013 Hall and Oates Threads and Grooves M RCA 2012 Adam Ant Playlist: The Very Best of Adam Ant P Epic/Legacy Dominic Miller 5th House M Ais / Q-Rious Music Clannad The Essential Clannad P RCA McFly Memory Lane: The Best of McFly M/P Island 2011 Sting The Best of 25 Years P/E/M Polydor/A&M Records Melissa Etheridge Icon P Island Van der Graaf Generator A Grounding in Numbers M Esoteric Records Various Artists Grandmaster II Project P/E/M Extreme 2010 The Bee Gees Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collections P/E/M Rhino Youssou N'Dour/Peter Gabriel Shakin' The Tree M Virgin Van der Graff Generator A Grounding In Numbers M Virgin Tina Turner Platinum Collection P/E/M Virgin Hall & Oates Collection: H2O, Private Eyes, Voices M RCA Tim Finn Anthology: North South East West P/E/M EMI Music Dist. Mummy Calls Mummy Calls P/E/M Geffen 311 Playlist: The Very Best of 311 P Legacy Various Artists Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P/E/M Sony Various Artists Rock For Amnesty P/E/M Mercury 2009 Tina Turner The Platinum Collection P Virgin Hall & Oates The Collection: H20/Private Eyes/Voices M RCA Bee Gees The Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collection P Rhino Dominic Miller In A Dream P/E/M Independent Lo-Star Closer To The Sun P/E/M Independent Danielle Harmer Superheroes P/E/M EMI Original Soundtrack Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P Sony Music Various Artists Grandmaster Project P/E/M Extreme Various Artists Now, Vol. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title (Reba McEntire & Vince Gill) 2 Pac 2 Pac The Heart Won't Lie High Till I Die When My Homies Call 10 Things I Hate About You Hit 'Em Up Words Of Wisdom Dazz Holler If Ya' Hear Me Young Black Male 10 Years How Do U Want It 2 Unlimited Wasteland How Long Will They Mourn Me? Get Ready For This 10,000 Maniacs I Ain't Mad At Cha 3 Days Grace Because The Night Belongs To I Came To Bring The Pain Pain Lovers I Don't Give A Fuck 3 Doors Down 100 Songs For Kids I Get Around Away From The Sun How Much Is That Doggy In The I'd Rather Be Your Nigga Be Like That Window If My Homie Calls Be Like That (Edit) You Are My Sunshine Keep Ya Head Up Behind Those Eyes 10000 Maniacs - Life Goes On Better Life Because The Night Belongs To Lost Soulz By My Side Lovers Me Against The World Down Poison 112 N.*.*.*.*. (Never Ignorant About Duck And Run Anywhere {Booty Bass Remix}{Ft. Getting Goals Accomplished) Here By Me Lil' Zane} One Day At A Time [Em's Version] Here Without You Dance With Me Outlaw (Feat Dramacydal) It's Not Me Peaches And Cream Panther Power Kryptonite U Already Know Pat Time Mutha Kryptonite (Acoustic) 12 Stones Picture Me Rollin' Life Of My Own The Way I Feel Rebel Of The Underground Loser 2 Live Crew Rebel Of The Underground My World Tootsie Roll Runnin' (Dying To Live) Never Will I Break 2 Pac Same Song Not Enough 2 Of Amerikaz Most Wanted Secretz Of War Smack Abitionz As A Ryder She's So Scandalous So Far Down All About U Smile So I Need You Baby Don't Cry So Many Tears 30 Seconds To Mars Brenda's Got A Baby Something Wicked The Kill Bury Me A G Soulja's Story 311 California Love [Original Version] Starin' Through My Rear View Amber Call The Cops When You See 2 Str8 Ballin' Pac Come Original Temptations Changes Feels So Good Tha' Lunatic Check Out Time (Feat Kurupt) Wobble Wobble The Realist Killaz Dear Mama 38 Special Thug Passion Death Around The Corner Hold On Loosley To Live & Die In L.A. -

Download Spring 2012

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta SPRING SUMMER 2012 Winter 2012 JEANETTE WINTERSON BACKLIST To coincide with the publication of Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Grove Press has commissioned new artwork by award-winning illustrator Olaf Hajek for the best-selling Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, The Passion, and Sexing the Cherry. Sexing the Cherry (978-0-8021-3578-0 • $14.95 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9870-9 The Passion (978-0-8021-3522-3 • $14.95 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-8021-9871-6 Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (978-0-8021-3516-2 • $14.95 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9872-3 MARCH 2012 “A highly unusual, scrupulously honest, and endearing memoir.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review) Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (978-0-8021-2010-6 • $25.00 • USO) eBook ISBN: 978-0-8021-9475-6 GROVE PRESS HARDCOVERS APRIL From the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award–winning author of the best-selling novel Man Gone Down comes a deeply personal, explosive memoir told through the stories of four generations of black American men in one family THE BROKEN KING A Memoir Michael Thomas Man Gone Down was: • One of The New York Times Book Review’s Ten Best Books eviewed on the cover of The New York Times Book Review and chosen of the Year as one of their Ten Best Books of 2008 before winning the IMPAC • Winner of the International R Dublin Literary Award, Man Gone Down introduced a new writer of IMPAC Dublin Literary Award prodigious and rare talent. -

For Alumni and Friends of Michigan State University

FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY • SUMMER 2015 By Geoff Koch riter Jim Harrison loathes interview re- quests from outsiders seeking to bask in his gruff wisdom, humor and writing prowess. “I AWAIT THE MIRACULOUS” I’ve been a fan of Harrison’s work since the In his twilight, writer Jim mid-2000s, when I found myself adrift in East Harrison—author of Legends of Lansing while my wife worked on her PhD at the Fall—remains hard at work, MSU. That first year I was disoriented by most and wants fellow MSU alums to everything, from the nasal “A”s to Lake Mich- know “I’m not dead yet!” igan. I needed a guide, someone to explain the spirit of the place, not just the names of the towns and landmarks. I stumbled onto the Photos and manuscript: books of Harrison, who ranks at or near the Courtesy of Grand Valley Special Collections & University Archives unless otherwise noted. top of famous writers among MSU alums, if not on the list of most prominent living American writers. Linda and Jim Harrison at the gravesite of William and Mary Wordsworth in St. Oswald’s, Grasmere, Cumbria, England, circa 1960s. 30 SUMMER 2015 | alumni.msu.edu Dan Gerber Guy de la Valdene arrison, an acute observer of culture and landscape, fami- lies and his own personal foibles, and who has mentioned MSU in most of his books, was more than up to the task. His work helped make Michigan feel like my second home. His books have kept me company no matter where I’ve lived since. -

Copper Canyon Reader Fall 2018 in MEMORIUM Please Visitourwebsite

It is my confirmed bias that the poets remain the most “stunned by existence,” the most determined to redeem the world in words. —C.D. Wright Copper Canyon Reader fall 2018 IN MEMORIUM Sam Hamill Founding Editor 1943–2018 from A PersonAl IntroductIon in The Gift of Tongues: Twenty-Five Years of Poetry from Copper Canyon Press(1996) I couldn’t, in my wildest dream, imagine a world in which my small gift would be multiplied by so many generous hands. But that is exactly how the gift of poetry works: the gift of inspiration is transformed by the poet into a body of sound which in turn is given away so that it may inspire and inform another, who in turn adds to the gift and gives it away again. For more information about Sam Hamill and the founding of Copper Canyon Press, please visit our website. The Chinese character for poetry is made up of two parts: “word” and “temple.” It also serves as pressmark for Copper Canyon Press. Ursula K. Le Guin So Far So Good NEW TITLE NEW “One of the troubles with our culture is we do not respect and train the imagination. It needs exercise. It needs practice. You can’t tell a story unless you’ve listened to a lot of stories and then learned how to do it.” to the rAIn Mother rain, manifold, measureless, falling on fallow, on field and forest, on house-roof, low hovel, high tower, downwelling waters all-washing, wider than cities, softer than sisterhood, vaster than countrysides, calming, recalling: return to us, teaching our troubled souls in your ceaseless descent to fall, to be fellow, to feel the root, to sink in, to heal, to sweeten the sea. -

Lumière Festival2016

LUMIÈRE FESTIVAL2016 WELCOME CATHERINE DENEUVE LUMIÈRE AWARD 2016 The program! From Saturday 8 to Sunday 16 October © Patrick Swirc - Modds Swirc © Patrick WELCOME to the Lumière festival! AM R G PRO E H Invitations to actresses and T actors, filmmakers, film music composers. RETROSPECTIVES Restored prints on the big screen in the theater: See films Catherine Deneuve: Lumière Award 2016 Buster Keaton, Part 1 in optimal conditions. An iconic incarnation of the accomplished actress and movie Inventive, a daredevil, touching, hilarious, Buster Keaton was star, this extraordinary actress shook up the art of the actor, all of these things at once, and revolutionized burlesque Huge film screenings at inspired filmmakers for five decades, through her amazing, comedy ofthe early 20th century, during the same era as the Halle Tony Garnier, the daring filmography, exploring all genres and forms. Films« carte Charlie Chaplin. His introverted but reckless character, forever Auditorium of Lyon and the Lyon blanche» (personal picks), a master class and presentation impassible and searching for love, would bring him great of the Lumière Award. notoriety. The Keaton Project, led by the Bologna Film Library Conference Center. and Cohen Films, allows us to dive into his work, currently Marcel Carné under restoration. Silent films accompanied by music to A discovery of silent films with Marcel Carné contributed some of his most successful films to discover with the whole family. cinema concerts. the cinema and invented poetic realism with Jacques Prévert. In his body of work, we come across Jean Gabin, Michèle Quentin Tarantino: 1970 Morgan, Louis Jouvet, Arletty, Simone Signoret, then rediscover Three years after receiving the Lumière Award, the cinephile Buster Keaton in The Cameraman Master classes and the opportunity to attend special Jacques Brel, Annie Girardot or Maurice Ronet.