Malaysia's New Cabinet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Najib's Fork-Tongue Shows Again: Umno Talks of Rejuvenation Yet Oldies Get Plum Jobs at Expense of New Blood

NAJIB'S FORK-TONGUE SHOWS AGAIN: UMNO TALKS OF REJUVENATION YET OLDIES GET PLUM JOBS AT EXPENSE OF NEW BLOOD 11 February 2016 - Malaysia Chronicle The recent appointments of Tan Sri Annuar Musa, 59, as Umno information chief, and Datuk Seri Ahmad Bashah Md Hanipah, 65, as Kedah menteri besar, have raised doubts whether one of the oldest parties in the country is truly committed to rejuvenating itself. The two stalwarts are taking over the duties of younger colleagues, Datuk Ahmad Maslan, 49, and Datuk Seri Mukhriz Mahathir, 51, respectively. Umno’s decision to replace both Ahmad and Mukhriz with older leaders indicates that internal politics trumps the changes it must make to stay relevant among the younger generation. In a party where the Youth chief himself is 40 and sporting a greying beard, Umno president Datuk Seri Najib Razak has time and again stressed the need to rejuvenate itself and attract the young. “Umno and Najib specifically have been saying about it (rejuvenation) for quite some time but they lack the political will to do so,” said Professor Dr Arnold Puyok, a political science lecturer from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. “I don’t think Najib has totally abandoned the idea of ‘peremajaan Umno’ (rejuvenation). He is just being cautious as doing so will put him in a collision course with the old guards.” In fact, as far back as 2014, Umno Youth chief Khairy Jamaluddin said older Umno leaders were unhappy with Najib’s call for rejuvenation as they believed it would pit them against their younger counterparts. He said the “noble proposal” that would help Umno win elections could be a “ticking time- bomb” instead. -

Senarai Penuh Calon Majlis Tertinggi Bagi Pemilihan Umno 2013 Bernama 7 Oct, 2013

Senarai Penuh Calon Majlis Tertinggi Bagi Pemilihan Umno 2013 Bernama 7 Oct, 2013 KUALA LUMPUR, 7 Okt (Bernama) -- Berikut senarai muktamad calon Majlis Tertinggi untuk pemilihan Umno 19 Okt ini, bagi penggal 2013-2016 yang dikeluarkan Umno, Isnin. Pengerusi Tetap 1. Tan Sri Badruddin Amiruldin (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Timbalan Pengerusi Tetap 1. Datuk Mohamad Aziz (Penyandang) 2. Ahmad Fariz Abdullah 3. Datuk Abd Rahman Palil Presiden 1. Datuk Seri Mohd Najib Tun Razak (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Timbalan Presiden 1. Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Naib Presiden 1. Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi (Penyandang) 2. Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Tun Hussein (Penyandang) 3. Datuk Seri Mohd Shafie Apdal (Penyandang) 4. Tan Sri Mohd Isa Abdul Samad 5. Datuk Mukhriz Tun Dr Mahathir 6. Datuk Seri Mohd Ali Rustam Majlis Tertinggi: (25 Jawatan Dipilih) 1. Datuk Seri Shahidan Kassim (Penyandang/dilantik) 2. Datuk Shamsul Anuar Nasarah 3. Datuk Dr Aziz Jamaludin Mhd Tahir 4. Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob (Penyandang) 5. Datuk Raja Nong Chik Raja Zainal Abidin (Penyandang/dilantik) 6. Tan Sri Annuar Musa 7. Datuk Zahidi Zainul Abidin 8. Datuk Tawfiq Abu Bakar Titingan 9. Datuk Misri Barham 10. Datuk Rosnah Abd Rashid Shirlin 12. Datuk Musa Sheikh Fadzir (Penyandang/dilantik) 13. Datuk Seri Ahmad Shabery Cheek (Penyandang) 4. Datuk Ab Aziz Kaprawi 15. Datuk Abdul Azeez Abdul Rahim (Penyandang) 16. Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed 17. Datuk Sohaimi Shahadan 18. Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh (Penyandang) 19. Datuk Seri Mahdzir Khalid 20. Datuk Razali Ibrahim (Penyandang/dilantik) 21. Dr Mohd Puad Zarkashi (Penyandang) 22. Datuk Halimah Mohamed Sadique 23. -

Marzuki Malaysiakini 24 Februari 2020 Wartawan Malaysiakini

LANGSUNG: Serah Dewan Rakyat tentukan Dr M jadi PM – Marzuki Malaysiakini 24 Februari 2020 Wartawan Malaysiakini LANGSUNG | Dengan pelbagai perkembangan semasa yang berlaku pantas dalam negara sejak semalam, Malaysiakini membawakan laporan langsung mengenainya di sini. Ikuti laporan wartawan kami mengenai gerakan penjajaran baru politik Malaysia di sini. Terima kasih kerana mengikuti laporan langsung Malaysiakini Sekian liputan kami mengenai keruntuhan kerajaan PH, Dr Mahathir Mohamad meletak jawatan sebagai perdana menteri dan pengerusi Bersatu. Terus ikuti kami untuk perkembangan penjajaran baru politik negara esok. Jika anda suka laporan kami, sokong media bebas dengan melanggan Malaysiakini dengan harga serendah RM0.55 sehari. Maklumat lanjut di sini. LANGSUNG 12.20 malam - Setiausaha Agung Bersatu Marzuki Yahya menafikan terdapat anggota parlimen atau pimpinan Bersatu yang di war-warkan keluar parti. Ini selepas Dr Mahathir Mohamad mengumumkan peletakan jawatan sebagai pengerusi Bersatu tengah hari tadi. Menurut Marzuki keputusan Bersatu keluar PH dibuat sebulat suara oleh MT parti. Ketika ditanya pemberita, beliau juga menafikan kemungkinan wujudnya kerjasama Pakatan Nasional. Menjelaskan lanjut, kata Marzuki tindakan Dr Mahathir itu "menyerahkan kepada Dewan Rakyat untuk menentukan beliau sebagai PM Malaysia. "Tidak timbul soal Umno, PAS atau mana-mana pihak. Ini terserah MP untuk sokong Tun (Dr Mahathir Mohamad) sebagai PM," katanya. 11.40 malam: Hampir 100 penyokong Bersatu berkumpul di luar ibu pejabat parti itu sementara menunggu para pemimpin mereka yang bermesyuarat malam ini. Apabila Ketua Pemuda Bersatu Syed Saddiq Abdul Rahman keluar dari bangunan itu, beliau dikerumuni para penyokongnya yang mula berteriak dan menolak pemberita bagi memberi laluan kepada Saddiq berjalan ke arah keretanya, yang menyebabkan sedikit keadaan sedikit kecoh. -

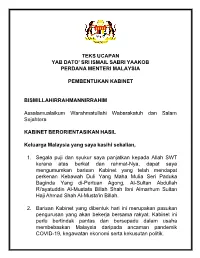

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

Di Lokasi Sede- Pence- Rxa'ssia'oauuwa"P'ebr"Lu2tana'g"Aiu" Se- Tetaypb}Kang

AKHBAR BERITA HARIAN MUKA SURAT :2 RUANGAN : NASIONAI Kuala Lumput: Penguatkuasaan hwalanPerBerakan Pe- Perintah khas yang dislarkan secara langsung di 'Aesen mulihan(PKPP) yang berakhir Is- Muhyiddin pada penihisan televFsyen, malam tadL nin ini, dilai'0utkan sehingga 31 Disember baharu dan perti kelab malam dan pusat hi: vagangga, Thwar rlan Sala rB He- pembudayaan norma perlor0utan tempoh norma baharu a(;ak sukar Susulan Perlis dan klus- pematuhan kepada SOP yang di- buran PKPP ihi, tindalcan. penguatkua- dah; Shglang di ditenislain oleh pihak saan akan penhn'g i' sauda- untuklmdiamalkan di lokasi sede- Pence- Rxa'ssia'oauuwa"p'ebr"lu2tana'g"aiu" se- tetaYpB}kang. berkuasa mengikut Akta ter membia- Katanya, kemasukan pelancong gera dan acawal dengan tbnda- ra-saudari mesti terus gahan dan Pengawalan Penyakit pe- asing juga masih tldak dibenar- kan tegas dan tangkas sebelinn ia sakan dirt dengan pemakaian Betjangkit 1988 (Akta 342). tangan, kan untuk mengelakkan penula- merebak dengan lebih meluas," ' lihip muka, membasuh Mengumiunkan keputusan ke- diri ran kes import ke dalam negara, katanya. senl'asa menjaga kebersihan rajaan itu, Perdana Menteri, Tan selain aktiviti sukan dibenarkan, Muhyid(tin menegaskan kera- dan mengelakkan berada tempat SriMuhyiddinYassin, berkatatin- tetapi tanpa pembabitan p(iserta jaan akan terus memperketatkan yang sesak," katanya. dakan itu adalah untuk memas- me- antarabangsa dan penonton. kawalan sempadan negara, Selb Perdam Menteri berkata, tikansemuapihakmematuhipro- "Dengan semangat sambutan mewajibkan warganegara yang, mandanpelitupmukaadalah sedur operasi standard (SOP) dan yang digu- --Hari Kebangsaan Ke-63 yang ber- pulanH dari luar tlan warga aging barangan keperluan " protokol kesihatan yang ditetap- inasa, Ke- tema Malaysia P&atin, saya me- yang masuk ke negara ini, mtin- nakan hampir setiap kan. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Hot Topics Wrapper

5/4/2021 Bernama - Budget 2021 A Catalyst For Country's Economy, Saviour For Those Affected By COVID-19 - Ministers wrapper Bahasa Malaysia Hot Topics A+ A A- Touchpoints Budget 2021 Budget 2021 Speech Fiscal Outlook and Federal Government Revenue Estimates 2021 Search - K2 Search - Categories Search - Contacts Search - Content Search - News Feeds Search - Web Links Search - Advanced Menu Main Ministry's Prole Finance Minister wwwold.treasury.gov.my/index.php/en/gallery-activities/news/item/7265-bernama-budget-2021-a-catalyst-for-country-s-economy,-saviour-for-those-affected-by-covid-19-ministers.html 1/7 5/4/2021 Bernama - Budget 2021 A Catalyst For Country's Economy, Saviour For Those Affected By COVID-19 - Ministers Deputy Minister of Finance Secretary General Chief Information Ocer Treasury's Prole Divisions & Units History Organization Chart Publication Calendar Gallery Activities Client's Charter Contact Us Sta Directory FAQs Home Gallery Activities News Bernama - Budget 2021 A Catalyst For Country's Economy, Saviour For Those Aected By COVID-19 - Ministers Friday, Nov 06 2020 wwwold.treasury.gov.my/index.php/en/gallery-activities/news/item/7265-bernama-budget-2021-a-catalyst-for-country-s-economy,-saviour-for-those-affected-by-covid-19-ministers.html 2/7 5/4/2021 Bernama - Budget 2021 A Catalyst For Country's Economy, Saviour For Those Affected By COVID-19 - Ministers MOF Services BUSINESS Online AGENCY Services MOF Mobile STAFF Application Microsite e- KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 6 - Budget 2021 tabled by Finance Minister Tengku Datuk Participation Seri Zafrul Tengku Abdul Aziz in the Dewan Rakyat today has been described as & Feedback a catalyst for the country's economy and a saviour for those aected by the COVID-19 pandemic. -

How the Pandemic Is Keeping Malaysia's Politics Messy

How the Pandemic Is Keeping Malaysia’s Politics Messy Malaysia’s first transfer of power in six decades was hailed as a milestone for transparency, free speech and racial tolerance in the multiethnic Southeast Asian country. But the new coalition collapsed amid an all-too-familiar mix of political intrigue and horse trading. Elements of the old regime were brought into a new government that also proved short-lived. The turmoil stems in part from an entrenched system of affirmative-action policies that critics say fosters cronyism and identity-based politics, while a state of emergency declared due to the coronavirus pandemic has hampered plans for fresh elections. 1. How did this start? Two veteran politicians, Mahathir Mohamad and Anwar Ibrahim, won a surprising election victory in 2018 that ousted then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, who was enmeshed in a massive money-laundering scandal linked to the state investment firm 1MDB. Mahathir, 96, became prime minister again (he had held the post from 1981 to 2003), with the understanding that he would hand over to Anwar at some point. Delays in setting a date and policy disputes led to tensions that boiled over in 2020. Mahathir stepped down and sought to strengthen his hand by forming a unity government outside party politics. But the king pre-empted his efforts by naming Mahathir’s erstwhile right-hand man, Muhyiddin Yassin, as prime minister, the eighth since Malaysia’s independence from the U.K. in 1957. Mahathir formed a new party to take on the government but failed to get it registered. -

Media Statement Malaysia Is Hosting the First Virtual Ief-Igu Ministerial Gas Forum

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UNIT PERANCANG EKONOMI JABATAN PERDANA MENTERI MEDIA STATEMENT MALAYSIA IS HOSTING THE FIRST VIRTUAL IEF-IGU MINISTERIAL GAS FORUM Kuala Lumpur, 1 Dec 2020 - Prime Minister of Malaysia, YAB Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin will inaugurate the 7th IEF-IGU Ministerial Gas Forum Roundtable this coming 3rd of December, that will be hosted by the Government of Malaysia represented through the Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department. The Ministerial Gas Forum, under the theme “Towards Recovery and Shared Prosperity: Natural Gas Opportunities for a Sustainable World”, is a biennial event jointly organised by International Energy Forum (IEF) and International Gas Union (IGU) and this 7th edition will be the first time the forum is held virtually. YB Dato’ Sri Mustapa Bin Mohamed, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Economy) will be hosting and jointly-moderating the ministerial forum together with Professor Joe Kang, the President of International Gas Union (IGU) and Mr Joseph McMonigle, the Secretary-General of International Energy Forum (IEF). The Ministerial Forum will be focusing on the inclusive dialogue highlighting the role of natural gas to strengthening energy security and facilitating the orderly energy transition in an increasingly carbon-constrained world. The two separate plenary sessions have been timed in such a way to encourage greater participation from 38 countries including Asia, North America, South America, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “Malaysia is honoured to be given the opportunity to be the host country of this biennial forum by the International Energy Forum (IEF) and the International Gas Union (IGU) . The forum will be addressing gas industry’s pressing issues amidst the current global 1 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE pandemic situation and to discuss mutually-beneficial solutions,” said Dato’ Sri Mustapa. -

Malaysian Newspaper Discourse and Citizen Participation

www.ccsenet.org/ass Asian Social Science Vol. 8, No. 5; April 2012 Malaysian Newspaper Discourse and Citizen Participation Arina Anis Azlan (Corresponding author) School of Media and Communication Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-4456 E-mail: [email protected] Samsudin A. Rahim School of Media and Communication Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-5832 E-mail: [email protected] Fuziah Kartini Hassan Basri School of Media and Communication Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-5908 E-mail: [email protected] Mohd Safar Hasim Centre of Corporate Communications Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-3-8921-5540 E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 26, 2012 Accepted: March 13, 2012 Published: April 16, 2012 doi:10.5539/ass.v8n5p116 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n5p116 This project is funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia under the research code UKM-AP-CMNB-19-2009/1 Abstract Newspapers are a particularly important tool for the communication of government agenda, policies and issues to the general public. An informed public makes for better democracy and active citizen participation, with citizens able to make well-informed decisions about the governance of their nation. This paper observes the role of Malaysian mainstream newspapers in the facilitation of citizen participation to exercise their political rights and responsibilities through a critical discourse analysis on newspaper coverage of the New Economic Model (NEM), a landmark policy of the Najib Administration. -

Racialdiscriminationreport We

TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Definition of Racial Discrimination......................................................................................................................... 4 Racial Discrimination in Malaysia Today................................................................................................................. 5 Efforts to Promote National Unity in Malaysia in 2018................................................................................... 6 Incidences of Racial Discrimination in Malaysia in 2018 1. Racial Politics and Race-based Party Politics........................................................................................ 16 2. Groups, Agencies and Individuals that use Provocative Racial and Religious Sentiments.. 21 3. Racism in the Education Sector................................................................................................................. 24 4. Racial Discrimination in Other Sectors................................................................................................... 25 5. Racism in social media among Malaysians........................................................................................... 26 6. Xenophobic -

Malaysia Daybreak | 30 August 2021 FBMKLCI Index

Malaysia | August 30, 2021 Key Metrics Malaysia Daybreak | 30 August 2021 FBMKLCI Index 1,700 ▌What’s on the Table… 1,650 ———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— 1,600 1,550 Strategy Note – Reaction to new cabinet and events to watch 1,500 Market likely to be neutral on the new cabinet as key ministers were retained. 1,450 This suggests there will be continuity to policies implemented previously. The 5% 1,400 gain in KLCI in the past week suggests market has priced in political stability in Aug-20 Oct-20 Dec-20 Feb-21 Apr-21 Jun-21 Aug-21 the near term. Maintain KLCI target of 1,608 pts and top picks. ——————————————————————————— FBMKLCI Bumi Armada – A robust 2Q21 as FPSO assets working well 1,590.16 4.42pts 0.28% 1H21 core net profit of RM361m was above expectations, at 82% of our full-year AUG Future SEP Future 1595 - (0.60%) 1579.5 - (0.45%) forecast (76% of consensus) due to better-than-forecast FPSO profits. Upgrade ——————————————————————————— from Hold to Add, with higher SOP-based TP of 55 sen as we raise our earnings Gainers Losers Unchanged forecasts and use a stronger US$ rate of RM4.15 (vs. RM4). Likely strong 2H21F 397 616 445 ——————————————————————————— earnings may re-rate the stock; share price is down 9% from its 16 Jun-high of 49 Turnover sen; a good opportunity to buy, in our view. 4083.21m shares / RM2960.129m 3m avg volume traded 5042.52m shares Public Bank Bhd – A prudent move to enhance provision buffer 3m avg value traded RM2963.34m ——————————————————————————— PBB’s 1H21 net profit was within expectations at 53% of our full-year forecast Regional Indices and 50% of the Bloomberg consensus estimate.