Tax Protestors and Penalties: Ensuring Perceived Fairness and Mitigating Systemic Costs Danshera Cords

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perelman, M. (2007). Some Economics of Class. in M. Yates (Ed.), More

Perelman, M. (2007). Some economics of class. In M. Yates (ed.), More unequal: Aspects of class in the United States. New York: Monthly Review Press. How much more will be required before the U.S. public awakes from its political slumber? Tepid action in the workplace, the voting booth, and the streets have allowed the right wing to steamroll revolutionary changes that have remade the entire sociopolitical structure of the United States. Since the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, every Democratic administration with the exception of Lyndon Johnson's has been more conservative—often far more conservative—than the previous Democratic administration. Similarly, every elected Republican administration, with the single exception of George Herbert Walker Bush's, has been more conservative than the previous Republican administration. The deterioration in the distribution of income is a symptom of a far larger problem. Perhaps formulating the situation in the United States might help people understand their class interests as well as reveal who has benefited from the right-wing revolution. Critics of Marx have long taken pleasure in claiming that the rise of the middle class in the United States and other advanced capitalist economies disproves Marx's "predictions" of the course of capitalism. In recent decades, however, the distribution of income in the United States is coming to resemble that of many poor Latin American economies, with a shrinking middle class and an obscene share of wealth going to the richest members of society. Although proponents of the U.S. model pretend that recent economic trends represent a success, in truth they are signs of capitalism's failure. -

Statement of Facts and Beliefs Forming the Basis of the Decision to Stop Filing and Paying the Individual Income Tax

STATEMENT OF FACTS AND BELIEFS FORMING THE BASIS OF THE DECISION TO STOP FILING AND PAYING THE INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX September 2003 (Attachment 2) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 4 POINT I THE INCOME TAX IS A TAX ON LABOR, PROHIBITED BY THE 13TH AMENDMENT 4 POINT II CONGRESS LACKS THE AUTHORITY TO LEGISLATE AN INCOME TAX ON THE PEOPLE EXCEPT IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, THE US TERRITORIES AND IN THOSE AREAS WITHIN ANY OF THE 50 STATES WHERE THE STATES HAVE SPECIFICALLY AUTHORIZED IT, IN WRITING 10 POINT III THE GOVERNMENT IS PROHIBITED BY THE 4TH AND 5TH AMENDMENTS FROM COMPELLING INDIVIDUALS TO SIGN AND FILE AN INCOME TAX RETURN FORM 1040 14 POINT IV PERSONAL INCOME TAXES POLARIZE AND DIVIDE AN OTHERWISE UNITED NATION AND PROMOTE CLASS WARFARE AND MISTRUST OF OUR GOVERNMENT. 15 POINT V THE 16TH AMENDMENT WAS NOT RATIFIED BY 3/4THS OF THE STATE LEGISLATURES AS REQUIRED BY ARTICLE 5 OF THE CONSTITUTION 18 POINT VI THE INTERNAL REVENUE CODE DOES NOT MAKE INDIVIDUALS LIABLE TO FILE A TAX RETURN AND PAY AN INCOME TAX 30 POINT VII THE INTERNAL REVENUE CODE IS VOID FOR VAGUENESS 33 POINT VIII UNLESS ONE IS A FOREIGNER WORKING HERE OR A CITIZEN OF THE U.S.A. EARNING HIS MONEY ABROAD HE IS NOT LIABLE FOR THE INCOME TAX 35 POINT IX MOST INDIVIDUALS ARE NOT REQUIRED TO FILE A FORM 1040 GIVEN THE FACT THAT ITS OMB CONTROL NUMBER RELATES TO REGULATORY SECTIONS THAT HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH MOST PEOPLE 37 POINT X THE IRS ROUTINELY VIOLATES 4TH AMENDMENT DUE PROCESS PROTECTIONS OF AMERICANS BY SEIZING ASSETS WITHOUT LAWFUL AUTHORITY OR A COURT -

Engagement Guidance on Corporate Tax Responsibility Why and How to Engage with Your Investee Companies

ENGAGEMENT GUIDANCE ON CORPORATE TAX RESPONSIBILITY WHY AND HOW TO ENGAGE WITH YOUR INVESTEE COMPANIES An investor initiative in partnership with UNEP Finance Initiative and UN Global Compact THE SIX PRINCIPLES We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and 1 decision-making processes. We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our 2 ownership policies and practices. We will seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by 3 the entities in which we invest. We will promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles 4 within the investment industry. We will work together to enhance our effectiveness in 5 implementing the Principles. We will each report on our activities and progress towards 6 implementing the Principles. CREDITS & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Authors: Athanasia Karananou and Anastasia Guha, PRI Editor: Mark Kolmar, PRI Design: Alessandro Boaretto, PRI The PRI is grateful to the investor taskforce on corporate tax responsibility for their contributions to the guidance: ■ Harriet Parker, Investment Analyst, Alliance Trust Investments ■ Steven Bryce, Investment Analyst, Arisaig Partners (Asia) Pte Ltd ■ Francois Meloche, Extra Financial Risks Manager, Bâtirente ■ Adam Kanzer, Managing Director, Domini Social Investments LLC ■ Pauline Lejay, SRI Officer, ERAFP ■ Meryam Omi, Head of Sustainability, Legal & General Investment Management ■ Robert Wilson, Research Analyst, MFS Investment Management ■ Michelle de Cordova, Director, Corporate Engagement & Public Policy, NEI Investments ■ Rosa van den Beemt, ESG Analyst, NEI Investments ■ Kate Elliot, Ethical Researcher, Rathbone Brothers Plc ■ Matthias Müller, Senior SI Analyst, RobecoSAM ■ Rosl Veltmeijer, Head of Research, Triodos Investment Management We would like to warmly thank Sol Picciotto, Emeritus Professor, Lancaster University and Coordinator, BEPS Monitoring Group, and Katherine Ng, PRI, for their contribution to the guidance. -

A Conceptual Framework for Tax Non-Compliance Studies in a Muslim Country: a Proposed Framework for the Case of Yemen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UUM Repository A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR TAX NON-COMPLIANCE STUDIES IN A MUSLIM COUNTRY: A PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR THE CASE OF YEMEN Lutfi Hassen Ali Al-Ttaffi & Hijattulah Abdul-Jabbar School of Accountancy, Universiti Utara Malaysia ABSTRACT The problem of tax noncompliance is widely described as a serious global phenomenon, especially in developing and least developing countries. Literatures indicate a number of factors that could possibly influence tax noncompliance behaviour but there is no single theory that can explain the phenomenon of tax noncompliance behaviour. Thus, researchers suggested that theories from sociology, psychology and economy could be useful in explaining tax behaviour. Perception and attitude of taxpayers are among the factors contributing towards compliance behaviour. In this regard, empirical evidence indicates that taxpayers act according to their belief and attitudes. Nevertheless, the specific attitude/view of Muslims towards tax has not been considered. Consequently, the purpose of this paper is to discuss the theoretical link between the influence of Islamic religious perspective and tax noncompliance behaviour. Furthermore, tax service quality, public governance quality and tax system structure, which are perceived as relevant to developing and least developing countries, were taken into consideration in the proposed framework. The paper concluded by urging future researchers to consider the relevancy of the Muslim-majority community in the future tax noncompliance studies. Keywords: tax noncompliance, Islamic religious perspective, public governance quality, tax service quality, tax system structure. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Tax noncompliance is one of the several phenomena that has affected the global economy, and thus has attracted the awareness of researchers in the area (Ross & McGee, 2012). -

Complexity, Compliance Costs and Non-Compliance with VAT by Small and Medium Enterprises (Smes) in Bangladesh: Is There a Relationship?

Complexity, Compliance Costs and Non-Compliance with VAT by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh: Is there a Relationship? Author Faridy, Nahida Published 2016 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1553 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367891 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Complexity, Compliance Costs and Non-Compliance with VAT by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh: Is there a Relationship? Nahida Faridy Bachelor in Economics (Hons), Dhaka University Masters in Economics, Dhaka University Masters in Taxation Policy and Management, Keio University Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics Griffith Business School Griffith University Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 Abstract The Value Added Tax (VAT), which has existed for 24 years in Bangladesh, has contributed some 37% on average to total tax revenue over the last 15 years (Saleheen, 2012; National Board of Revenue, 2014). Although, the introduction of a VAT has increased tax revenues and expanded the tax base in Bangladesh, many small and medium enterprise (SME) taxpayers do not comply with the VAT legislation, not only failing to register with the tax authorities as taxpayers but also failing to pay the VAT (Faridy et al., 2014; The Centre for Policy Dialogue, 2014). This non-compliance by SMEs could be intentional or unintentional (NBR, 2011; McKerchar, 2003). Also it may be due to excessive compliance costs (Abdul-Jabbar & Pope, 2009; Governance Institutes Network International, 2014), which could be a result of real or perceived legislative or administrative complexity (Yesegat, 2009), to inefficient VAT administration (Barbone et al., 2012), or to other factors. -

Do Audits Deter Or Provoke Future Tax Noncompliance? Evidence on Self-Employed Taxpayers

WP/19/223 Do Audits Deter or Provoke Future Tax Noncompliance? Evidence on Self-employed Taxpayers by Sebastian Beer, Matthias Kasper, Erich Kirchler, and Brian Erard © 2019 International Monetary Fund WP/19/223 IMF Working Paper Fiscal Affairs Department Do Audits Deter or Provoke Future Tax Noncompliance? Evidence on Self-employed Taxpayers Prepared by Sebastian Beer, Matthias Kasper, Erich Kirchler, and Brian Erard Authorized for distribution by Ruud de Mooij October 2019 IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management. Abstract This paper employs unique tax administrative data and operational audit information from a sample of approximately 7,500 self-employed U.S. taxpayers to investigate the effects of operational tax audits on future reporting behavior. Our estimates indicate that audits can have substantial deterrent or counter-deterrent effects. Among those taxpayers who receive an additional tax assessment, reported taxable income is estimated to be 64% higher in the first year after the audit than it would have been in the absence of the audit. In contrast, among those taxpayers who do not receive an additional tax assessment, reported taxable income is estimated to be approximately 15% lower the year after the audit than it would have been had the audit not taken place. Our results suggest that improved targeting of audits towards noncompliant taxpayers would not only yield more direct audit revenue, it would also pay dividends in terms of future tax collections. -

September 11 & 12 . 2008

n e w y o r k c i t y s e p t e m b e r 11 & 12 . 2008 ServiceNation is a campaign for a new America; an America where citizens come together and take responsibility for the nation’s future. ServiceNation unites leaders from every sector of American society with hundreds of thousands of citizens in a national effort to call on the next President and Congress, leaders from all sectors, and our fellow Americans to create a new era of service and civic engagement in America, an era in which all Americans work together to try and solve our greatest and most persistent societal challenges. The ServiceNation Summit brings together 600 leaders of all ages and from every sector of American life—from universities and foundations, to businesses and government—to celebrate the power and potential of service, and to lay out a bold agenda for addressing society’s challenges through expanded opportunities for community and national service. 11:00-2:00 pm 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE Organized by myGoodDeed l o c a t i o n PS 124, 40 Division Street SEPTEMBER 11.2008 4:00-6:00 pm REGIstRATION l o c a t i o n Columbia University 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE 6:00-7:00 pm OUR ROLE, OUR VOICE, OUR SERVICE PRESIDENTIAL FORUM& 101 Young Leaders Building a Nation of Service l o c a t i o n Columbia University Usher Raymond, IV • RECORDING ARTIST, suMMIT YOUTH CHAIR 7:00-8:00 pm PRESIDEntIAL FORUM ON SERVICE Opening Program l o c a t i o n Columbia University Bill Novelli • CEO, AARP Laysha Ward • PRESIDENT, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND TARGET FOUNDATION Lee Bollinger • PRESIDENT, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Governor David A. -

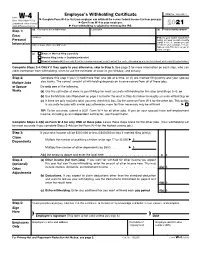

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY March 5, 1996 In

* * * PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY March 5, 1996 In accordance with the Warrant the polls were opened at 7:00 a.m. and closed at 8:00 p.m. The voters cast their ballots in their respective precincts. The results were as follows: DEMOCRATIC PARTY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 TOTAL PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE Bill Clinton 24 59 24 21 39 81 71 57 63 25 464 Lyndon N. LaRouche Jr 0 3 0 0 0 2 1 5 1 1 13 No Preference 1 1 1 0 3 2 0 5 3 1 17 All Others 3 1 0 0 1 0 0 4 0 2 11 Blanks 0 0 3 0 2 0 2 2 2 0 11 TOTAL 28 64 28 21 45 85 74 73 69 29 516 STATE COMMITTEE MAN Stanley C. Rosenberg 23 55 27 20 35 74 61 63 61 27 446 Blanks 5 9 1 1 10 11 13 10 8 2 70 TOTAL 28 64 28 21 45 85 74 73 69 29 516 STATE COMMITTEE WOMAN Mary L. Ford 22 48 22 17 29 60 56 55 52 22 383 All Others 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Blanks 6 16 6 4 16 25 18 18 17 7 133 TOTAL 28 64 28 21 45 85 74 73 69 29 516 TOWN COMMITTEE Mary Sidney Treyz 11 17 16 11 17 15 31 26 40 24 208 Florence C. Frank 10 21 16 12 19 22 28 28 45 21 222 Dolores D. -

April New Books

BROWNELL LIBRARY NEW TITLES, APRIL 2018 FICTION F ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Queen Anne's lace / Berkley Prime Crime, 2018 While helping Ruby Wilcox clean up the loft above their shops, China comes upon a box of antique handcrafted lace and old photographs. Following the discovery, she hears a woman humming an old Scottish ballad and smells the delicate scent of lavender. Soon strange things start occurring. Could the building be haunted? F ARDEN Arden, Katherine. The bear and the nightingale: a novel / Del Rey, 2017 A novel inspired by Russian fairy tales follows the experiences of a wild young girl who taps the mysterious powers of a precious necklace given to her father years earlier to save her village from dark and dangerous forces. F BALDACCI Baldacci, David. The fallen / Grand Central Publishing, 2018 Amos Decker and his journalist friend Alex Jamison are visiting the home of Alex's sister in Barronville, a small town in western Pennsylvania that has been hit hard economically. When Decker is out on the rear deck of the house talking with Alex's niece, a precocious eight-year- old, he notices flickering lights and then a spark of flame in the window of the house across the way. When he goes to investigate he finds two dead bodies inside and it's not clear how either man died. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. There's something going on in Barronville that might be the canary in the coal mine for the rest of the country. Faced with a stonewalling local police force, and roadblocks put up by unseen forces, Decker and Jamison must pull out all the stops to solve the case. -

IRS Publication 4128, Tax Impact of Job Loss

Publication 4128 Tax Impact of Job Loss The Life Cycle Series A series of informational publications designed to educate taxpayers about the tax impact of significant life events. Publication 4128 (Rev. 5-2020) Catalog Number 35359Q Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service www.irs.gov Facts JOB LOSS CREATES TAX ISSUES References The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) recognizes that the loss of a job may • Publication 17, Your create new tax issues. The IRS provides the following information to Federal Income Tax (For assist displaced workers. Individuals) • Severance pay and unemployment compensation are taxable. • Publication 575, Payments for any accumulated vacation or sick time are also Pension and Annuity taxable. You should ensure that enough taxes are withheld from Income these payments or make estimated payments. See IRS Publication 17, Your Federal Income Tax, for more information. • Publication 334, Tax Guide for Small • Generally, withdrawals from your pension plan are taxable unless Businesses they are transferred to a qualified plan (such as an IRA). If you are under age 59 1⁄2, an additional tax may apply to the taxable portion of your pension. See IRS Publication 575, Pension and Annuity Income, for more information. • Job hunting and moving expenses are no longer deductible. • Some displaced workers may decide to start their own business. The IRS provides information and classes for new business owners. See IRS Publication 334, Tax Guide for Small Businesses, for more information. If you are unable to attend small business tax workshops, meetings or seminars near you, consider taking Small Business Taxes: The Virtual Workshop online as an alternative option. -

Class of 2003 Finals Program

School of Law One Hundred and Seventy-Fourth FINAL EXERCISES The Lawn May 18, 2003 1 Distinction 2 High Distinction 3 Highest Distinction 4 Honors 5 High Honors 6 Highest Honors 7 Distinguished Majors Program School of Law Finals Speaker Mortimer M. Caplin Former Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service Mortimer Caplin was born in New York in 1916. He came to Charlottesville in 1933, graduating from the College in 1937 and the Law School in 1940. During the Normandy invasion, he served as U.S. Navy beachmaster and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach. He continued his federal service as Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service under President Kennedy from 1961 to 1964. When he entered U.Va. at age 17, Mr. Caplin committed himself to all aspects of University life. From 1933-37, he was a star athlete in the University’s leading sport—boxing—achieving an undefeated record for three years in the mid-1930s and winning the NCAA middleweight title in spite of suffering a broken hand. He also served as coach of the boxing team and was president of the University Players drama group. At the School of Law, he was editor-in-chief of the Virginia Law Review and graduated as the top student in his class. In addition to his deep commitment to public service, he is well known for his devotion to teaching and to the educational process and to advancing tax law. Mr. Caplin taught tax law at U.Va. from 1950-61, while serving as president of the Atlantic Coast Conference.