An Analysis of the Causes of the Global Financial Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLA Developments in Corporations Law June 2018

Recent developments in corporate law CLA June Judges series 8 June 2018 Ashley Black A Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales Introduction This note reviews several developments in corporations and insolvency law as at June 2018. I first note three recently decided cases as to directors’ duties and oppression, then several cases decided since the introduction of the Insolvency Law Reform Act 2016 (Cth), and then consider important recent case law as to the liquidation of trustee companies and disclaimers of onerous property. I will also refer to an interesting recent example of a freezing order granted in an external administration. I will then note the introduction of a safe harbour from liability for insolvent trading to facilitate corporate restructurings and a stay on the use of ipso facto clauses to amend or terminate contracts with a company that is placed in voluntary administration. I will also refer to recent developments as financial benchmark manipulation and penalties for breach of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Directors’ duties and oppression Judgment has recently been given in the penalty hearing of the long running proceedings against Mr and Mrs Cassimatis, the directors and sole shareholders of Storm Financial Ltd (“Storm”). In the liability judgment 1, Edelman J held that Mr and Mrs Cassimatis had contravened s 180 of the Corporations Act in exercising their powers as directors of Storm in a manner that caused or permitted (by omission) inappropriate advice to be given by that entity to a particular class of investors who were, inter alia, retired or close to retirement and had little or no prospect of rebuilding their financial position if they suffered substantial loss. -

1. Gina Rinehart 2. Anthony Pratt & Family • 3. Harry Triguboff

1. Gina Rinehart $14.02billion from Resources Chairman – Hancock Prospecting Residence: Perth Wealth last year: $20.01b Rank last year: 1 A plunging iron ore price has made a big dent in Gina Rinehart’s wealth. But so vast are her mining assets that Rinehart, chairman of Hancock Prospecting, maintains her position as Australia’s richest person in 2015. Work is continuing on her $10billion Roy Hill project in Western Australia, although it has been hit by doubts over its short-term viability given falling commodity prices and safety issues. Rinehart is pressing ahead and expects the first shipment late in 2015. Most of her wealth comes from huge royalty cheques from Rio Tinto, which mines vast swaths of tenements pegged by Rinehart’s late father, Lang Hancock, in the 1950s and 1960s. Rinehart's wealth has been subject to a long running family dispute with a court ruling in May that eldest daughter Bianca should become head of the $5b family trust. 2. Anthony Pratt & Family $10.76billion from manufacturing and investment Executive Chairman – Visy Residence: Melbourne Wealth last year: $7.6billion Rank last year: 2 Anthony Pratt’s bet on a recovering United States economy is paying off. The value of his US-based Pratt Industries has surged this year thanks to an improving manufacturing sector and a lower Australian dollar. Pratt is also executive chairman of box maker and recycling business Visy, based in Melbourne. Visy is Australia’s largest private company by revenue and the biggest Australian-owned employer in the US. Pratt inherited the Visy leadership from his late father Richard in 2009, though the firm’s ownership is shared with sisters Heloise Waislitz and Fiona Geminder. -

Cba Financial Planning Scandal

July 2014 SMSF Specialists Investment Management Financial Planning Accounting Thompson. Both Phil and Alastair each have over 30 years prac- ticing experience and are assisted by two recent accounting IN THIS ISSUE graduates, Kushal Sharma and Ivan Yeung as well as two further • GFM Accounting – get organised early! support staff, Miryam Schejtmen and Shimla Prasad. • CBA Financial Planning Scandal The constant frustration of many of our clients is that their • 2013/14 Financial Year – Another Bumper Year current accountants do not provide pro-active accounting • Jack Watt – Client of GFM since 1996 advice, rather “they go through the motions” without any real • Deeming of Account Based Pensions from thought of tax minimisation. The GFM Gruchy team work hard 1 January 2015 to ensure you get pro-active accounting. It is critically important you ensure your accounting affairs are well • Staff Profile – Denise Slattery structured and managed and you pay the least amount of • Upcoming seminar - Monday 18th August 2014 at tax possible. 12.00 noon – Estate Planning Creating Certainty • Superannuation, Centrelink Age Pension benefits Our accounting firm is not only able to help with personal & Personal Taxation impact from the 2014 Federal returns but can also assist with the following services: Budget – Seminar June 2014 • Partnership Returns • Upcoming new website launch • Family Trust Returns • “Best Interests Duty” – Who is your financial adviser • Company Tax Returns really working for? • Wealthy investors favour SMSF’s • Business Activity Statements • Do you know where you are going? • Bookkeeping Services • Compulsory Superannuation Guarantee Charge • Financial Statements With the end of financial year 2013/14 just finished, we are in a strong position to be able to assist you with your personal tax GFM ACCOUNTING: returns for those that want to get organised early and possibly GET ORGANISED EARLY! get their refund ASAP. -

Alternative Investment News November 10, 2008

ain111008 6/11/08 19:18 Page 1 NOVEMBER 1O, 2008 LEHMAN/NOMURA PRIME BROKER VOL. IX, NO. 45 INTEGRATION HITS SYSTEMS SNAG Credit Suisse Cuts Combining the prime brokerage businesses of Nomura FoF Headcount Holdings and Lehman Brothers has reportedly hit a costly and The firm has trimmed 10 staffers from its fund of funds unit, with most of the unexpected snag that could delay full integration for an culled positions based in Europe. undetermined time, potentially stretching to several months or See story, page 9 over a year. An official involved with the merger integration plans told AIN that in Nomura’s acquisition of Lehman’s Asia, India and At Press Time European operations, it received the software for Lehman’s cash Zaragoza Likes Biotechs 2 prime brokerage system—which includes trading, analytics and (continued on page 19) The Americas Nonprofits To Add HFs 4 MELLON SUSPENDS SANCTUARY FUNDS Peloton Pro Sets Up Shop 4 Mellon Global Alternative Investments has suspended dealings on the $344 million Mellon RCG Bullish On Asia 6 Sanctuary Fund and the $426 million Mellon Sanctuary Fund II—its flagship event-driven Startup Readies Managed Account 7 and relative-value funds of hedge funds—as liquidity concerns have arisen from Europe unprecedented volatility in the markets. A number of the underlying funds “have invoked German Shop Revisits Launches 9 provisions that are intended for periods such as this where acute market illiquidity is coupled Pioneer Keen On Green 10 with extreme selling pressure,” stated an email sent to AIN by Spokesman Jamie Brookes. Mulvaney Sees Record Highs 11 (continued on page 20) Asia Pacific EX-FSA EXEC: SMALLER FUNDS NEED Infrastructure Firm Hires Trio 12 CLOSER SUPERVISION Japan Launch Pushed Back 13 The U.K.’s Financial Services Authority should monitor the behaviour of smaller hedge Middle East & Africa fund firms more closely because malpractice is more likely to go unnoticed in these firms. -

2014/06: Should There Be Severe Restrictions Placed on Cyclists Sharing

2014/06: Should there be severe restrictions placed on cyclists sharing ... file:///C:/DPfinal/schools/adocs/doca2014/2014bikes/2014bikes.php 2014/06: Should there be severe restrictions placed on cyclists sharing roads with motorised vehicles? What they said... 'Bicycles reduce traffic congestion because they use road space more efficiently than cars' The Greens Bicycle Action Plan for Victoria 'A bit like smoking, if the idea of riding bicycles on the open road was invented today, it would be banned' Michael Pascoe, contributing editor to The Sydney Morning Herald The issue at a glance On January 1, 2014, it was announced that despite record low fatality rates across the country for motorists, 2013 had seen record high rates for the number of cyclists being killed. This apparent anomaly has led commentators, lobby groups and various state governments to consider a variety of measures to increase cyclists' safety. On January 17, 2014, Michael Pascoe, a contributing editor to The Sydney Morning Herald proposed that Australian governments might 'extend the culture of enforced safety to greater regulation of where and when people are allowed to cycle'. The idea that severe restrictions be placed on when and where cyclists can cycle is not new. Former New South Wales Roads Minister, Carl Scully, stated in 2009, 'I believed riding a bike on a road was profoundly unsafe and that where I could I would shift them [cyclists] to off road cycle ways.' Such a proposal has been welcomed by many motorists and some cyclists; however, it has been rejected by others as unduly limiting, unfeasible and too expensive. -

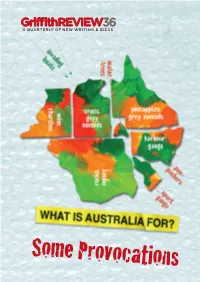

Griffith REVIEW Editon 36: What Is Australia For?

36 A QUARTERLY OF NEW WRITING & IDEAS ESSAYS & MEMOIR, FICTION & REPORTAGE Frank Moorhouse, Kim Mahood, Jim Davidson, Robyn Archer Dennis Altman, Michael Wesley, Nick Bryant, Leah Kaminsky, Romy Ash, David Astle, Some Provocations Peter Mares, Cameron Muir, Bruce Pascoe GriffithREVIEW36 SOME PROVOCATIONS eISBN 978-0-9873135-0-8 Publisher Marilyn McMeniman AM Editor Julianne Schultz AM Deputy Editor Nicholas Bray Production Manager Paul Thwaites Proofreader Alan Vaarwerk Editorial Interns Alecia Wood, Michelle Chitts, Coco McGrath Administration Andrea Huynh GRIFFITH REVIEW South Bank Campus, Griffith University PO Box 3370, South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Ph +617 3735 3071 Fax +617 3735 3272 [email protected] www.griffithreview.com TEXT PUBLISHING Swann House, 22 William St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Ph +613 8610 4500 Fax +613 9629 8621 [email protected] www.textpublishing.com.au SUBSCRIPTIONS Within Australia: 1 year (4 editions) $111.80 RRP, inc. P&H and GST Outside Australia: 1 year (4 editions) A$161.80 RRP, inc. P&H Institutional and bulk rates available on application. COPYRIGHT The copyright of all material published in Griffith REVIEW and on its website remains the property of the author, artist or photographer, and is subject to copyright laws. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. ||| Opinions published in Griffith REVIEW are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, Griffith University or Text Publishing. FEEDBACK AND COMMENT www.griffithreview.com ADVERTISING Each issue of Griffith REVIEW has a circulation of at least 4,000 copies. Full-page adverts are available to selected advertisers. -

Ex-Commonwealth PM Set to Launch $500M Macro Fund LAUNCH

The long and the short of it www.hfmweek.com ISSUE 497 3 MAY 2018 INFRAHEDGE CEO BRUCE KEITH DEPARTS AFTER 7 YEARS HFM EUROPEAN 2018 $30bn MAP co-founder to be replaced by Andrew Allright PEOPLE MOVES 03 PERFORMANCE AWARDS DEUTSCHE PUTS PRIME FINANCE BUSINESS UNDER REVIEW HF head Tarun Nagpal to leave bank after 15 years PRIME BROKERAGE 07 EX-GRUSS CAPITAL PROS PREP EVENT-DRIVEN FUND HFMWEEK REVEALS ALL Indar Capital expected to launch later this year LAUNCHES 10 THE WINNERS AWARDS 23 Ex-CommonWealth PM set to launch $500m macro fund Christopher Wheeler readies between 2013 and 2016. London-based CJW Capital CommonWealth closed BY SAM MACDONALD down last year as Fisher depart- ed to join $26bn Soros Fund FORMER CITADEL AND Management. CommonWealth Opportunity From November 2016 until Capital portfolio manager Chris- March this year, Wheeler is topher Wheeler is set to launch a understood to have traded a sub- LAUNCH macro fund with at least $500m stantial macro sleeve for Citadel. initial investment, HFMWeek He previously spent five years has learned. with London-based liquid multi- ANALYSIS Wheeler is starting London- asset business Talisman Global NUMBERS SURGE IN 2017 based CJW Capital Management Asset Management. He earlier with backing from a large asset worked at Morgan Stanley. manager and is looking to begin CJW Capital could become trading this year, HFMWeek one of this year’s largest HFM Global’s annual survey shows understands. European start-ups, amid a num- He registered the firm with ber of prominent macro hedge equity strategies remained most in UK Companies House on 23 fund launches. -

2020 NRMA Kennedy Awards' Finalists

2020 NRMA Kennedy Awards’ Finalists Media release embargoed 7pm, Wednesday 22 July 2020 Categories and finalists 1 Les Kennedy Award for Outstanding Crime Reporting - Simon Bouda (A Current Affair); Australian Story: An Innocent Abroad (ABC); Michael Usher and team: Framed, the story of Scott Austic (7 News) 2 Paul Lockyer Award for Outstanding Regional Broadcast Reporting (sponsor AGL) – Prime 7 Local News - Coast Team; Jane Goldsmith (NBN News); ABC Background Briefing/Landline 3 Chris Watson Award for Outstanding Regional Newspaper Reporting (sponsor AGL) – Carla Hildebrandt (Mandurah Mail); Madeline Link (Northern Daily Leader); The Tumut and Adelong Times, Tumbarumba Times 4 Rod Allen Award for Racing Writer of the Year (sponsor Australian Turf Club) – Damien Ractliffe, Chip Le Grand (The Age); Ray Thomas (Daily Telegraph); Chris Roots (Sydney Morning Herald 5 Sean Flannery Award for Outstanding Radio Journalism (sponsor Hillbrick Bicycles) – Gavin Coote (ABC Audio Current Affairs); Steve Cannane and Kyle Taylor (ABC Background Briefing); Elini Psaltis (World Today ABC) 6 Outstanding Podcast (sponsor broadcast voice coach Sally Prosser) – Mark Whittaker: Blood Territory; Kimberley Pratt and Stephanie Coombes: First Person series (10 News First); The Eleventh (ABC Radio Programs) 7 Outstanding News Photo (sponsor Salty Dingo) – Sam Ruttyn (Sunday Telegraph); Nick Moir (Sydney Morning Herald); Dallas Kilponen (freelance pic for the Sydney Morning Herald) 8 Outstanding Portrait (sponsor Salty Dingo) – Richard Dobson (Sunday Telegraph); -

Mis-Conduct in Financial Services in Australia

Part I: mis-conduct in financial services in Australia I thought that it might be useful to see what has been happening in Australia, which has suffered a string of large financial services frauds and other bad conduct, often linked to the country’s largest banks. At the end of 2017, the Australian government set up a Royal Commission to look at bad practices in retail banking. This follow a number of serious scandals involving the main commercial banks in Australia. The Commission issued it interim report in September this year and this will be covered in a separate report on the UCL Centre for Ethics and Law web-site. While the Australian financial system came out well from the 2007/8 financial crisis, in recent years there has been a steady stream of major cases demonstrating unethical behaviour. These have mainly involved mis-advice but also fraud and outright theft. Examples include Westpoint involving the loss of some A$388m (the chief financial officer was convicted), Trio/Astarra with a loss of A$180m with eleven people convicted and Sonray Capital Markets with the founder, Russell Johnson, jailed for fraud.1 Many of these firms were connected with the four major Australian banks.2 For example, Commonwealth Financial Planning Limited (CFPL) was the financial planning division of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. Many of CFPL’s staff mis-advised many thousands of customers leading to an investigation by the Australian Senate Economics References Committee which in a press release in 2014 described the “conduct of a number of CFPL advisers [as] unethical, dishonest, [and] well below professional standards and a grievous breach of their duties”.3 “The problem is that some people in the industry have lost their moral compass. -

Michael Pascoe

2020 Exchange Pty Ltd ABN 86 161 073 927 Suite 503, 55 Lime Street King Street Wharf Sydney NSW 2000 1300 550 618 www.2020Exchange.com.au FACILITATOR PROFILE – MICHAEL PASCOE “The difference between leadership & management has become a cliché, but that hasn’t closed the gap. 2020 Exchange is that leap into pure leadership.” Michael Pascoe is one of Australia’s most experienced and respected finance and economics commentators. With four decades in newspaper, broadcast and on-line journalism covering the full spectrum of economic and business issues, Michael also is a an accomplished speaker, MC and facilitator. Michael was born and educated in Queensland and started his career with The Courier-Mail before working in Hong Kong for three years with the South China Morning Post. Upon returning to Australia, he joined the Australian Financial Review in Sydney and then pioneered specialist finance journalism in commercial broadcasting, first with the Macquarie Radio network and subsequently with Channel 9, Sky News and Channel Seven. Probably best known for his 18 years as the Nine Network’s Finance Editor, Michael conceived, presented and produced the ground-breaking Business Today program in the late 1980s and was the senior interviewer and reporter on Business Sunday from its inception. He has the ability to interpret complex finance issues or world events and explain them to broadcast and live audiences. His broad grasp of the global events and domestic policies impacting on our economy allows him to provide thought-provoking opinions and test the theories of our politicians, business leaders and economists. After a spell as founding Associate Editor for Alan Kohler’s Eureka Report and business correspondent for Crikey.com.au, Michael now brings those talents and an occasional touch of mischievous humour to his current role as Contributing Editor for Australia’s most-read business publications, the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age BusinessDay.com.au sites. -

Report: Statutory Oversight of the Australian Securities And

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services Statutory oversight of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission February 2011 © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 ISBN 978-1-74229-405-6 Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra ii Members of the Committee Mr Bernie Ripoll, Chairman QLD ALP Senator Sue Boyce, Deputy Chair QLD LP Senator Annette Hurley SA ALP Senator the Hon Ursula Stephens NSW ALP Senator Mathias Cormann WA LP Mr Paul Fletcher MP NSW LP Mr Hon Alan Griffin MP VIC ALP Ms Laura Smyth MP VIC ALP Mr Tony Smith MP VIC LP SECRETARIAT Dr Ian Holland, Secretary Dr Robyn Clough, Principal Research Officer Ms Erin East, Principal Research Officer Ms Christina Schwarz, Administrative Officer Ms Ruth Edwards, Administrative Officer Suite SG.64 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 T: 61 2 6277 3583 F: 61 2 6277 5719 E: [email protected] W: www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/corporations_ctte iii Duties of the Committee Section 243 of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 sets out the Parliamentary Committee's duties as follows: (a) to inquire into, and report to both Houses on: (i) activities of ASIC or the Panel, or matters connected with such activities, to which, in the Parliamentary Committee's opinion, the Parliament's attention should be directed; or (ii) the operation of the corporations legislation (other than the excluded provisions), or of any other law of the Commonwealth, of a State or Territory or of a foreign country that appears to the Parliamentary -

Market Failure, Regulation and Education of Financial Advisors

Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 2 2016 Market Failure, Regulation and Education of Financial Advisors Adam Steen Charles Sturt University, Australia, [email protected] Dianne McGrath Charles Sturt University, Australia Alfred Wong Charles Sturt University, Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/aabfj Copyright ©2016 Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal and Authors. Recommended Citation Steen, Adam; McGrath, Dianne; and Wong, Alfred, Market Failure, Regulation and Education of Financial Advisors, Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 10(1), 2016, 3-17. doi:10.14453/aabfj.v10i1.2 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Market Failure, Regulation and Education of Financial Advisors Abstract This paper explores the recent series of financial scandals in the ustrA alian financial advice industry. It examines the causes, consequences and responses to these scandals by financial institutions, investors and regulators through the lens of relevant finance theory and extant literature. Although the paper focuses on the recent Australian experience the discussion and findings presented are of relevance to financial market regulation worldwide. It is proposed that a combination of compensation, education, training and structural reforms are required to reduce the undesirable effects of information asymmetry, adverse selection and moral hazard in the finance sector. Keywords Financial planning scandals, financial advice, egulation,r financial literacy This article is available in Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal: https://ro.uow.edu.au/aabfj/vol10/ iss1/2 Market Failure, Regulation and Education of Financial Advisors Adam Steen1, Dianne McGrath2 and Alfred Wong3 Abstract This paper explores the recent series of financial scandals in the Australian financial advice industry.