Tardid, an Iranian Adaptation of Hamlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

Persian 1103 Course Change.Pdf

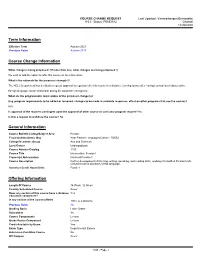

COURSE CHANGE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 1103 - Status: PENDING Chantal 11/20/2020 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2021 Previous Value Autumn 2015 Course Change Information What change is being proposed? (If more than one, what changes are being proposed?) We wish to add the option to offer this course as an online class. What is the rationale for the proposed change(s)? The NELC Department has decided to request approval to regularly offer this course in a distance learning format after having learned much about online foreign language course instruction during the pandemic emergency. What are the programmatic implications of the proposed change(s)? (e.g. program requirements to be added or removed, changes to be made in available resources, effect on other programs that use the course)? N/A Is approval of the requrest contingent upon the approval of other course or curricular program request? No Is this a request to withdraw the course? No General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Persian Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Near Eastern Languages/Culture - D0554 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Undergraduate Course Number/Catalog 1103 Course Title Intermediate Persian I Transcript Abbreviation Intermed Persian 1 Course Description Further development of listening, writing, speaking, and reading skills; reading of simplified Persian texts. Closed to native speakers of this language. Semester Credit Hours/Units Fixed: 4 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 12 Week Flexibly -

King and Karabell BS

k o No. 3 • March 2008 o l Iran’s Global Ambition t By Michael Rubin u While the United States has focused its attention on Iranian activities in the greater Middle East, Iran has worked O assiduously to expand its influence in Latin America and Africa. Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s out- reach in both areas has been deliberate and generously funded. He has made significant strides in Latin America, helping to embolden the anti-American bloc of Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nicaragua. In Africa, he is forging strong n ties as well. The United States ignores these developments at its peril, and efforts need to be undertaken to reverse r Iran’s recent gains. e t Both before and after the Islamic Revolution, Iran Iranian officials have pursued a coordinated has aspired to be a regional power. Prior to 1979, diplomatic, economic, and military strategy to s Washington supported Tehran’s ambitions—after expand their influence in Latin America and a all, the shah provided a bulwark against both Africa. They have found success not only in communist and radical Arab nationalism. Follow- Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia, but also in E ing the Islamic Revolution, however, U.S. officials Senegal, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. These new viewed Iranian visions of grandeur warily. alliances will together challenge U.S. interests in e This wariness has grown as the Islamic Repub- these states and in the wider region, especially if l lic pursues nuclear technology in contravention Tehran pursues an inkblot strategy to expand its d to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty safe- influence to other regional states. -

La Discapacidad Visual En El Cine Iraní

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL La discapacidad visual en el cine iraní MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Zahra Razi Directora Isabel Martín Sánchez . Madrid Ed. electrónica 2019 © Zahra Razi, 2019 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias de la Información Departamento de Periodismo y Comunicación global TESIS DOCTORAL La discapacidad visual en el cine iraní MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR Autora: Zahra Razi Directora: Dra. Isabel Martín Sánchez Madrid, 2018 I Agradecimientos En primer lugar quiero agradecer de manera destacada a mi directora, Dra. Isabel Martín Sánchez, la confianza que ha mostrado en esta investigación desde el principio, el apoyo constante durante el desarrollo de la tesis y el intenso trabajo en los últimos meses para concluir este trabajo de investigación. Le agradezco la confianza, apoyo y dedicación de tiempo a mis profesores: Dra. María Antonia Paz, Dr. Francisco García García, Dr. Bernardino Herrera León, Dr. Joaquín Aguirre Romero, Dr. Vicente Baca Lagos y Dr. Emilio Carlos García por haber compartido conmigo sus conocimientos y sobre todo su amistad. Además, quiero agradecer a la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, la posibilidad que me ofreció de realizar, entre 2012 y 2014, el Máster en Comunicación Social, cuyo trabajo final es el embrión de esta tesis doctoral en 2018, que me abrió la puerta a una realidad social, hasta entonces conocida pero no explorada, como es el mundo de la discapacidad visual en el cine iraní. A Ana Crespo, por ser parte de mi vida académica, gracias por su apoyo, comprensión y sobre todo amistad y dedicación de tiempo. -

Water Dispute Escalating Between Iran and Afghanistan

Atlantic Council SOUTH ASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Water Dispute Escalating between Iran and Afghanistan AUGUST 2016 FATEMEH AMAN Iran and Afghanistan have no major territorial disputes, unlike Afghanistan and Pakistan or Pakistan and India. However, a festering disagreement over allocation of water from the Helmand River is threatening their relationship as each side suffers from droughts, climate change, and the lack of proper water management. Both countries have continued to build dams and dig wells without environmental surveys, diverted the flow of water, and planted crops not suitable for the changing climate. Without better management and international help, there are likely to be escalating crises. Improving and clarifying existing agreements is also vital. The United States once played a critical role in mediating water disputes between Iran and Afghanistan. It is in the interest of the United States, which is striving to shore up the Afghan government and the region at large, to help resolve disagreements between Iran and Afghanistan over the Helmand and other shared rivers. The Atlantic Council Future Historical context of Iran Initiative aims to Disputes over water between Iran and Afghanistan date to the 1870s galvanize the international when Afghanistan was under British control. A British officer drew community—led by the United States with its global allies the Iran-Afghan border along the main branch of the Helmand River. and partners—to increase the In 1939, the Iranian government of Reza Shah Pahlavi and Mohammad Joint Comprehensive Plan of Zahir Shah’s Afghanistan government signed a treaty on sharing the Action’s chances for success and river’s waters, but the Afghans failed to ratify it. -

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things. -

Selection of Iranian Films 2020

In the Name of God PUBLISHER Farabi Cinema Foundation No. 59, Sie Tir Ave., Tehran 11358, Iran Management: Tel: +98 21 66708545 / 66705454 Fax: +98 21 66720750 [email protected] International Affairs: Tel: +98 21 66747826 / 66736840 Fax: +98 21 66728758 [email protected] / [email protected] http://en.fcf.ir Editor in Chief: Raed Faridzadeh Teamwork by: Mahsa Fariba, Samareh Khodarahmi, Elnaz Khoshdel, Mona Saheb, Tandis Tabatabaei. Graphics, Layout & Print: Alireza Kiaei A SELECTION OF IRANIAN FILMS 2020 CONTENTS Films 6 General Information 126 Awards 136 Statistics 148 Films Film Title P.N Film Title P.N A BALLAD FOR THE WHITE COW 6 NO PLACE FOR ANGELS 64 ABADAN 1160 8 PLUNDER 66 AMPHIBIOUS 10 PUFF PUFF PASS 68 ATABAI 12 RELY ON THE WIND 70 BANDAR BAND 14 RESET 72 BECAME BLOOD 16 RIOT DAY 74 BONE MARROW 18 THE NIGHT 76 BORN OF THE EARTH 20 THE BLACK CAT 78 CARELESS CRIME 22 THE BLUE GIRL 80 CINEMA SHAHRE GHESEH 24 THE ENEMIES 82 CROWS 26 THE FOURTH ROUND 84 DAY ZERO 28 THE GOOD, THE BAD,THE INDECENT 2 86 DROWN 30 THE GREAT LEAP 88 DROWNING IN HOLY WATER 32 THE INHERITANCE 90 EAR RINGED FISH 34 THE LADY 92 EXCELLENCY 36 THE MARRIAGE PROJECT 94 EXODUS 38 THE RAIN FALLS WHERE IT WILL 96 FATHERS 40 THE REVERSED PATH 98 FILICIDE 42 THE SKIN 100 FORSAKEN HOMES 44 THE SLAUGHTERHOUSE 102 I’M HERE 46 THE STORY OF FORUGH’S GIRL 104 I’M SCARED 48 THE SUN 106 IT’S WINTER 50 THE UNDERCOVER 108 KEEP QUIET SNAIL 52 THE WASTELAND 110 KILLER SPIDER 54 TITI 112 LIFE AMONG WAR FLAGS 56 TOOMAN 114 LUNAR ECLIPSE 58 WALKING WITH THE WIND 116 NARROW RED LINE 60 WALNUT TREE 118 NO CHOICE 62 A BALLAD FOR THE WHITE COW (Ghasideye Gaveh Sefid) Directed by: Behtash Sanaeeha Synopsis: Written by: Behtash Sanaeeha, Maryam Mina’s husband has just been executed Moghadam, Mehrdad Kouroshnia for murder. -

C O N T E N T S 34Th Fajr Film Festival 2 22 Movies to Compete in 34Th

مجله داخل پروازی هواپیمایی ماهان فجر Mahan Inflight Magazine Fajr Proprietor: Mahan Air Co. Managing Director: Mehdi Aliyari Central Office: Communication and International Relations Department, 4th Floor, Mahan Air Tower, Azadegan St., Karaj High- way, Tehran,Iran P.O.Box: 14515411 Tel: 021-48381752 Fax: 021- 48381799 Email: [email protected] Advertisement: Tel: (+9821) 24843 Fax: (+9821) 22050045 Cellphone: 09121129144 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 34th Fajr Film Festival 2 22 Movies to Compete in 34th Fajr Film Festival 3 Top Rivals at 34th Fajr Film Festival 4 Nine foreign Plays to Compete in Fajr Festival 7 Fajr Theater Festival to Host 30 Special Int'l Guests 8 Top 100 Most Anticipated Foreign Films of 2016: #23. Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman 9 34th Fajr Film Festival 1-11 February 2016 Tehran, Iran Fajr Film Festival is Iran's annual film festival, held every February from 1-11 in Tehran, Iran. The festival, started in 1982, is under the supervision of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance in Iran. It takes place every year on the anniversary of the Iranian revolution. Page 3 | Health Page 4 | Fajr 22 Movies to Compete in 34th Fajr Film Festival 22 domestic movies would compete in the biggest cinematic event of the country to be held in February. A total of 22 movies, including Bodyguard, 'Wooden Lollipop', 'The Dragon Enters', 'Lanturi' (literally meaning numpty), 'Being Born', 'The World Redemption', 'The Girl', 'Barcode', 'Anger and Hubbub', 'Cyanide', 'Scandal', 'Malaria', 'Breath', 'Blind Point', 'Midnight' and 'Inversion' compete in the section. Top Rivals at 34th Fajr Film Festival Films by famous young and veteran directors vie for the Crystal Simorgh awards at the 34th Fajr Film Festival next month. -

Iranian Cinema Syllabus Winter 2017 Olli Final Version

Contemporary Iranian Cinema Prof. Hossein Khosrowjah [email protected] Winter 2017: Between January 24and February 28 Times: Tuesday 1-3 Location: Freight & Salvage Coffee House The post-revolutionary Iranian national cinema has garnered international popularity and critical acclaim since the late 1980s for being innovative, ethical, and compassionate. This course will be an overview of post-revolutionary Iranian national cinema. We will discuss and look at works of the most prominent films of this period including Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Bahram Beyzaii, and Asghar Farhadi. We will consider the dominant themes and stylistic characteristics of Iranian national cinema that since its ascendance in the late 1980s has garnered international popularity and critical acclaim for being innovative, ethical and compassionate. Moreover, the role of censorship and strong feminist tendencies of many contemporary Iranian films will be examined. Week 1 [January 24]: Introduction: The Early Days, The Birth of an Industry Class Screenings: Early Ghajar Dynasty Images (Complied by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 18 mins) The House is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963) Excerpts from Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992) 1 Week 2 [January 31]: New Wave Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, The Revolution, and the First Cautious Steps Pre-class viewing: 1- Downpour (Bahram Beyzai, 1972 – Required) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-gCtDWHFQI 2- The Report (Abbas Kiarostami, 1977 – Recommended) http://www.veoh.com/watch/v48030256GmyJGNQw 3- The Brick -

Ahmadinejad's Principalist Doctrine: Sovereign Rights to a Nuclear Arsenal

Ahmadinejad’s Principalist Doctrine: Sovereign Rights to a Nuclear Arsenal Farhad Rezaei Center for Iranian Studies (IRAM), Ankara, Turkey January 2017 Abstract Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won the election in 2005, on behalf of the Principalists, a hardline secular opposition, that considered the clerical establishment corrupt and soft on foreign policy. In particular, the Principalists railed against the NPT, describing it as a product of Western hegemony. Ahmadinejad asserted that Iran, like other nations, had a sovereign right to run a nuclear program. Hinting broadly that Iran would not be dissuaded from weaponizing, Ahmadinejad proceeded to fashion a “civil religion” around the alleged nuclear prowess of Iran. Nuclear Day was celebrated around the country as part of a new secular nationalist identity. But in his customary contradictory and occasionally unpredictable and even bizarre manner, the president also claimed that pursuing the nuclear program is part of his mission ordained by the Mahdi. Ahmadinejad’s “in your face” nuclear diplomacy, coupled with his penchant for messianic visions and denial of the Holocaust, rattled the West. Unsure whether Ahmadinejad spoke for himself or for the regime, the international community became alarmed that Iran crossed the threshold from nuclear rationality to messianic irrationality. The SC reacted by imposing a series of increasingly punitive sanctions on Iran. References: 1. Goodenough, Patrick. 2010. No Sign of International Unity on Iran After Administration’s Latest Deadline Passes. CNS News, January 26. http://www.cnsnews.com/news/article/no-sign- international-unity-iran-after-administration-s-latest-deadline-passes 2. Adebahr, Cornelius. 2014. Tehran Calling: Understanding a New Iranian Leadership. -

Calcareous Cave Discovered in W Azarbaijan Province

Art & Culture February 15, 2018 3 This Day in History Calcareous Cave Discovered (February 15) Today is Thursday; 26th of the Iranian month of Bahman 1396 solar hijri; corresponding to 28th of the Islamic month of Jamadi al-Awwal 1439 lunar hijri; and February 15, 2018, of the Christian Gregorian Calendar. 1428 solar years ago, on this day in 590 AD, Khosrow II was crowned the 22nd in W Azarbaijan Province Sassanid Emperor of Persia, following his revolt against his father, Hormizd IV, who was deposed, blinded and killed. Grandson of Khosrow I (Anushirvan), he styled Simineh District, and en route Iran formed in the course of time and himself Perviz (Victorious) but lacked the traits of virtue, as was evident by incidents gas transfer pipeline to Turkey. presently, it is completely dried.” during his 38-year reign that ended in 628 with his torturous death in prison at the hands of his generals, after he had torn the letter of invitation to Islam from the Almighty’s He pointed to the discovery of this Given the sensitivity of resi- Last and Greatest Messenger, Prophet Mohammad (SAWA), and threatened to attack calcareous cave by the project com- dents of the village with regard to Hijaz from Iranian-controlled Yemen, following the reversal of his fortunes in the 26- missioner and added, “This natural maintain this cave intact, a min- year long Roman-Iranian War. Within a year of his accession he was ousted by the and historical work is located as ute was concluded between rural rebellious general, Bahram Chubin, fled via Syria to Constantinople, and regained the throne of Ctesiphon in 1591 with help from Emperor Maurice of Byzantium (Eastern depth as five meters of the land and councilors and contractor of the Roman Empire). -

Mullahs, Guards, and Bonyads: an Exploration of Iranian Leadership

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Mullahs, Guards, and Bonyads An Exploration of Iranian Leadership Dynamics David E.