2 Transcendental and Anthropomorphic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELI 3850: God in Israel: Historical Encounters NOTE THIS COURSE OUTLINE IS NOT FINAL UNTIL the FIRST DAY of CLASS

RELI 3850: God in Israel: Historical Encounters NOTE THIS COURSE OUTLINE IS NOT FINAL UNTIL THE FIRST DAY OF CLASS. The most up‐to‐date version of the syllabus is on CULearn CARLETON UNIVERSITY GOD IN ISRAEL: HISTORICAL ENCOUNTERS COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES RELI 3850: TOPICS IN STUDY OF RELIGION ABROAD RELIGION PROGRAM Israel: May 4‐27, 2014 Dr. Deidre Public course web site for info and uploading blogs [email protected] about the course www.carleton.ca/studyisrael Dr. Shawna Dolansky Official Course Facebook page: public fb page for [email protected] friends and families to see where we are going. Post photos, videos, tweet about the course. https://www.facebook.com/studyisraelwithZC CU Learn site for readings and grades Description: This third‐year travel course will survey religious history through geographical exploration of famous sites all over Israel: biblical Israel at the Temple Mount; origins of Christianity out of Judaism in the Galilee and in Jerusalem; Second Temple Judaism at Qumran and Masada; Rabbinic Judaism in ancient synagogues and in a special exhibit at the Israel Museum; the Crusades at the ruins of a Crusader fortress; Jewish mysticism in 17th century Safed; the Holocaust at Yad Vashem; modern Israel at the Knesset, a kibbutz, the Baha’i Temple in Haifa, and the beaches of Tel Aviv. Required Texts: Required readings This travel course includes travel in Israel from prepare you for class lectures, May 4‐27 with course requirements beginning discussions and site visits. Always read before travel. the required text prior to the site visit. Course Requirements: Required texts include online readings 30% Participation linked through the CU Learn web site 20% Presentation or Web Page 50% Blogs or Research paper see details below YOUR PROFESSORS: As the Jewish Studies specialist of the Religion Program, Professor Deidre Butler brings together her general expertise in Jewish Studies and Religion with an emphasis on contemporary Jewish life, modern Jewish thought, Holocaust, and gender and sexuality. -

Once Again, Nationality and Religion

genealogy Article Once Again, Nationality and Religion Steven E. Grosby Department of Philosophy and Religion, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA; [email protected] Received: 22 July 2019; Accepted: 5 September 2019; Published: 8 September 2019 Abstract: An examination of the relation between nationality and religion calls for comparative analysis. There is a variability of the relation over time and from one nation and religion to another. At times, nationality and religion have clearly converged; but there have also been times when they have diverged. Examination of this variability may lead to generalizations that can be achieved through comparison. While the generalizations achieved through a comparative analysis of the relation are heuristically useful, there are complications that qualify those generalizations. Moreover, while further refining the comparative framework of the relation between nationality and religion remains important, it is not the pressing theoretical problem. That problem is ascertaining what is distinctive of religion as a category of human thought and action such that it is distinguishable from nationality and, thus, a variable in the comparative analysis. It may be that determining that distinctiveness results in the need for a different framework to analyze the relation between nationality and religion. Keywords: axial age; kinship; monolatry; monotheism; nation; priest; religion; territory 1. Introduction Examination of the relation between nationality and religion calls for comparative analysis. -

ANGELS in ISLAM a Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl

ANGELS IN ISLAM A Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al- malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels) S. R. Burge Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2009 A loose-leaf from a MS of al-Qazwīnī’s, cAjā’ib fī makhlūqāt (British Library) Source: Du Ry, Carel J., Art of Islam (New York: Abrams, 1971), p. 188 0.1 Abstract This thesis presents a commentary with selected translations of Jalāl al-Dīn cAbd al- Raḥmān al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al-malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels). The work is a collection of around 750 ḥadīth about angels, followed by a postscript (khātima) that discusses theological questions regarding their status in Islam. The first section of this thesis looks at the state of the study of angels in Islam, which has tended to focus on specific issues or narratives. However, there has been little study of the angels in Islamic tradition outside studies of angels in the Qur’an and eschatological literature. This thesis hopes to present some of this more general material about angels. The following two sections of the thesis present an analysis of the whole work. The first of these two sections looks at the origin of Muslim beliefs about angels, focusing on angelic nomenclature and angelic iconography. The second attempts to understand the message of al-Suyūṭī’s collection and the work’s purpose, through a consideration of the roles of angels in everyday life and ritual. -

Divine Principle & Angels (V1.6)

Divine Principle & Angels Introduction v 1.6 Recense of an Angel Artist Benny Andersson Introduction • This is an attempt to collect what the Bible and Divine Principle and True Father has spoken about Angels. • Included is some folklore from the Unif. movement. You decide what’s true. Background • The word angel in English is a blend of Old English engel (with a hard g) and Old French angele. Both derive from Late Latin angelus "messenger of God", which in turn was borrowed from Late Greek ἄγγελος ángelos. According to R. S. P. Beekes, ángelos itself may be "an Oriental loan, like ἄγγαρος ['Persian mounted courier']." • Angels, in a variety of religions, are regarded as spirits. They are often depicted as messengers of God in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles and the Quran. • Daniel is the first biblical figure to refer to individual angels by name, mentioning Gabriel (God's primary messenger) in Daniel 9:21 and Michael (the holy fighter) in Daniel 10:13. These angels are part of Daniel's apocalyptic visions and are an important part of all apocalyptic literature Orthodox icon from Saint Catherine's Monastery, representing the archangels Michael and Gabriel. Along with Rafael counted as archangels of Jews, Christians and Muslims. • The conception of angels is best understood in contrast to demons and is often thought to be "influenced by the ancient Persian religious tradition of Zoroastrianism, which viewed the world as a battleground between forces of good and forces of evil, between light and darkness." One of these "sons of God" is "the satan", • a figure depicted in (among other places) the Book of Job. -

Fortune Telling

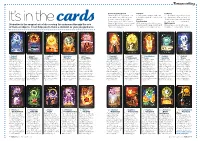

Fortune telling How to use the spread Intuition Dowsing Relax and focus on the question Slowly open your eyes and then Using a pendulum, ask it to show you want to ask - this can be as select the card that you feel most you a movement for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. general or specific as you like. drawn to. Then hover it over each card until It’s in the Then, using one of the following Psychometry you get a ‘yes’ - this is your card. forms of divination, choose a card With your eyes closed, run your Bibliomancy Divination is the magical art of discoveringcards the unknown through the use and read the summary you have hand across the page and stop at Close your eyes and with your of tools or objects. It can help you to make a decision or give you guidance chosen for guidance. the card you feel is right for you. finger point to any card at random. Gabriel Hanael Jophiel Metatron Uriel Zaphkiel Jophiel Sandalphon Zadkiel Gabriel 1 Balance 2Willpower 3 Joy 4 Miracles 5 Friendship 6 Surrender 7 Forgiveness 8 Love 9 Security 10 Grace Gabriel wants you to The great whales of The card you have Miracles are changes Uriel wishes you to The angels want you to Jophiel asks you to let This angelic oracle The angels unite The oracle of Gabriel know that you have the oceans deep are chosen brings forth a of perception and know that the true know that you are go of the pain of the comes to you as with their powerful wishes you to receive been too busy. -

Ancient Origins of Religious Universalism Peter R

Ancient Origins of Religious Universalism Peter R. Bedford, Union College (A précis, of sorts) It is commonly considered By HeBrew BiBle scholars that monotheism in Ancient Israel—and By ‘monotheism’ I mean the Belief that there is only one God and that other ‘gods’ people worship are in fact figments of human imagination, idols that do not exist— emerged around the middle of the first millennium BCE in the context of Israel’s political subjugation and exile at the hands of successive Near Eastern empires, the Neo-Assyrian, Neo-BaBylonian, and the Achaemenid Persian empires. Imperialism is key here since the political sovereignty of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah was undermined By these empires and with it the royal-state ideology that averred that Yahweh, the god of these kingdoms, was their sovereign lord who superintended their affairs and well-being. The political power of these foreign empires compromised the authority of Yahweh since it very much looked like their gods had greater authority than the god of Israel and Judah and that these imperial gods dictated what would happen to Israel and Judah, their kings and their peoples. One reaction of a suBjugated people to the demonstrated power of successive empires and their chief deities—Assur for Assyria, Marduk for Babylonia, Ahura Mazda for Persia—is simply to recognize that your own god is one among many who serves the Great God of the empire in the heavenly court, and so suBjugated peoples here on earth must serve the Great King of the empire who acts as the imperial god’s vicegerent. -

Archangel Kindle

ARCHANGEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sharon Shinn | 10 pages | 01 Dec 1997 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780441004324 | English | New York, United States Archangel PDF Book She has a great love of nature, people, and the planet, and she enjoys her connection in spirit, both here and in heaven. The energy of the mouse is quiet productivity of the multitudes, while the groundhog digs deeper for answers and represents the world of dreams, the opossum represents family nurturing, and the skunk and raccoon represent the cleanup crew. Any time you or someone you love is experiencing sadness due to loneliness, call on Archangel Uriel to help to see the wonders that exist within your soul or the soul for whom you are praying. Know that the reality, is there are far more Archangels serving behind the scenes. Michael the Archangel. Become a fundraiser to help us collect, clone, archive the genetics, and replant these important trees for future generations. These cookies do not store any personal information. In this book I provide many guided meditations audio and experiments that help you discover more ways to deeply connect with Michael. In human form, Raquel appears with wings in flowing white robes and a large book in hand. Additionally, this Archangel symbolically appears in the form of fish, representing the fluidity of divine communications, situations of divine emotional importance, and the surreal world of dreams. Moscow Official as Yakov Rafalson. External Reviews. Uriel presents three impossible riddles to show us how humans cannot fathom the ways of God. Archangel Jophiel provides assistance with refocusing on positive experiences of life, encouraging inner journeys which lead to the discovery of soul-specific solutions for your life's passions, and raising your energy levels and thoughts toward the light to inspire the giving and receiving of unconditional love. -

A N G E L S (Amemjam¿) 1

A N G E L S (amemJam¿) 1. Brief description 2. Nine orders of Angels 3. Archangels and Other Angels 1. Brief description of angels * Angels are spiritual beings created by God to serve Him, though created higher than man. Some, the good angels, have remained obedient to Him and carry out His will. Lucifer, whose ambitions were a distortion of God's plan, is known to us as the fallen angel, with the use of many names, among which are Satan, Belial, Beelzebub and the Devil. * The word "angelos" in Greek means messenger. Angels are purely spiritual beings that do God's will (Psalms 103:20, Matthew 26:53). * Angels were created before the world and man (Job 38:6,7) * Angels appear in the Bible from the beginning to the end, from the Book of Genesis to the Book of Revelation. * The Bible is our best source of knowledge about angels - for example, Psalms 91:11, Matthew 18:10 and Acts 12:15 indicate humans have guardian angels. The theological study of angels is known as angelology. * 34 books of Bible refer to angels, Christ taught their existence (Matt.8:10; 24:31; 26:53 etc.). * An angel can be in only one place at one time (Dan.9:21-23; 10:10-14), b. Although they are spirit beings, they can appear in the form of men (in dreams – Matt.1:20; in natural sight with human functions – Gen. 18:1-8; 22: 19:1; seen by some and not others – 2 Kings 6:15-17). * Angels cannot reproduce (Mark 12:25), 3. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Jon D. Levenson Contents

CURRICULUM VITAE Jon D. Levenson Contents: Personal and Educational pp. 1–2 Areas of Specialization p. 2 Foreign Study p. 2 Prizes and Commendations p. 2–3 Teaching Experience pp. 3 Professional Societies p. 3–4 Offices Held pp. 4 Consulting Experience p. 4 Publications pp. 4–16 Academic Presentations pp. 17–28 Other Presentations pp. 28–40 Education: Ph.D. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, 1975 M.A. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, 1974 B.A. summa cum laude in English, Harvard College, 1971 Areas of Specialization: Theological traditions in ancient Israel (biblical and rabbinic periods) Literary Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible Midrash History of Jewish biblical interpretation Modern Jewish theology Jewish-Christian relations Foreign Study: One year of research in Jerusalem, Israel, on a full-salary grant from Wellesley College, 1980–81 Modern Hebrew language and culture at Ulpan Akiva, Netanya, Israel, summer 1971. Granted certificate from the Ministry of Education and Culture Italian language and art at the Centro di Cultura per Stranieri, University of Florence, Italy, summer 1968 Jon D. Levenson, CV Prizes and Commendations: Listed as one of “The Top 100 People Positively Influencing Jewish Life, 2015,” by the Algemeiner Journal. Listing by Choice of Inheriting Abraham: The Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as one of the Outstanding Academic Titles, 2013. Honorable Mention for the PROSE Award in Theology and Religious Studies, Association of American Publishers (for Resurrection: The Power of God for Christians and Jews, co-authored with Kevin J. Madigan), 2008. -

Jewish-Christian Dialogue About Covenant Ruth Langer Center for Christian-Jewish Learning, Boston College

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 2, Issue 2 (2007): CP10-15 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING Jewish-Christian Dialogue about Covenant Ruth Langer Center for Christian-Jewish Learning, Boston College Delivered at the Houston Clergy Institute, March 6, 2007 In 2002, the dialogue held between the US Catholic Bishop’s Committee on Ecumenical and Interfaith Affairs and the National Council of Synagogues issued a statement called “Reflections on Covenant and Mission.” Reflecting on the developments in Catholic teaching about Jews and Judaism since Nostra Aetate, issued in 1965, the Catholic part of the statement took the daring step of affirming that if God’s covenant with the Jews is eternally valid, then it must be salvific for Jews, and thus there is no justification for a Christian mission directed to Jews. There is no reason that Jews ought to become Christians. This statement was quite controversial. It received serious criticism not only from parts of the Protestant world, but also from some significant Catholic theologians. How could Christians simply dismiss Jesus’ commission to his disciples? When the resurrected Jesus appears in the Galilee, he commands, “All power in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you.” (Mt 28:18b-20a)1 I begin with this, not because I plan to talk about Christian understandings of covenant, but because I want to highlight what has been termed “theological dialogue.”2 This isn’t a dialogue about how we should respond together to poverty or social justice issues in our society. -

Chapter Four—Divinity

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER FOUR The Ritual-Architectural Commemoration of Divinity: Contentious Academic Theories but Consentient Supernaturalist Conceptions (Priority II-A).............................................................485 • The Driving Questions: Characteristically Mesoamerican and/or Uniquely Oaxacan Ideas about Supernatural Entities and Life Forces…………..…………...........…….487 • A Two-Block Agenda: The History of Ideas about, then the Ritual-Architectural Expression of, Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity……………………......….....……...489 I. The History of Ideas about Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity: Phenomenological versus Social Scientific Approaches to Other Peoples’ God(s)………………....……………495 A. Competing and Complementary Conceptions of Ancient Zapotec Religion: Many Gods, One God and/or No Gods……………………………….....……………500 1. Ancient Oaxacan Polytheism: Greco-Roman Analogies and the Prevailing Presumption of a Pantheon of Personal Gods..................................505 a. Conventional (and Qualified) Views of Polytheism as Belief in Many Gods: Aztec Deities Extrapolated to Oaxaca………..….......506 b. Oaxacan Polytheism Reimagined as “Multiple Experiences of the Sacred”: Ethnographer Miguel Bartolomé’s Contribution……...........514 2. Ancient Oaxacan Monotheism, Monolatry and/or Monistic-Pantheism: Diverse Arguments for Belief in a Supreme Being or Principle……….....…..517 a. Christianity-Derived Pre-Columbian Monotheism: Faith-Based Posits of Quetzalcoatl as Saint Thomas, Apostle of Jesus………........518 b. “Primitive Monotheism,” -

Authorship of the Pentateuch

M. Bajić: Authorship of the Pentateuch Authorship of the Pentateuch Monika Bajić Biblijski institut, Zagreb [email protected] UDK:27-242 Professional paper Received: April, 2016 Accepted: October, 2016 Summary This piece is a concise summary of the historical and contemporary develo- pment of Pentateuch studies in Old Testament Theology. This article aims to provide information on the possible confirmation of Mosaic authorship. The purpose is to examine how the Documentary Hypothesis, Fragment and Su- pplemental Hypotheses, Form and Traditio-Historical Criticism, Canonical and Literary Criticism have helped to reveal or identify the identity of the author of the Torah. To better understand the mentioned hypotheses, this article presents a brief description of the J, E, D, and P sources. Key words: Pentateuch, authorship, Mosaic authorship, Torah, Documen- tary Hypothesis, Fragment and Supplemental Hypothesis, Form and Tradi- tio-Historical Criticism, Canonical and Literary Criticism. In the most literal sense, the Pentateuch 1 (or Torah) is an anonymous work, but traditional views support the belief of Mosaic authorship (Carpenter 1986, 751- 52). Yet, with the advent of humanism and the Renaissance, the sense of intellec- tual freedom and upswing in research have led to the fact that many have begun to read the Bible critically, trying to challenge its text as well as the traditions and beliefs that are formed from it (Alexander 2003, 61-63). One of the most commonly attacked beliefs is Moses’ authorship of the Torah. There has been an 1 Taken from the Greek translation LXX. Pentateuch is derived from the Greek word pentateu- chos, which means a five-book work, known as the Books of Moses (Carpenter 1986).