Getting Schooled: Lessons from a Semester with the IYWP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bonny Levine – 2016 Table of Contents

Bonny LeVine – 2016 Table of Contents Bonny LeVine At A Glance ............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Lisa Almeida – CEO, Freedom Boat Club ........................................................................................................................................................11 Cheryl Bachelder – CEO, Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen, Inc ................................................................................................................................14 Jania Bailey – CEO, FranNet Franchising, LLC .................................................................................................................................................18 Cathy Brown – Franchisee Owner & Area Director, Jersey Mike’s Subs .......................................................................................................... 22 Stacy Brown – Founder, Chicken Salad Chick ................................................................................................................................................. 26 Amy Cheng – Partner, Cheng Cohen, LLC .......................................................................................................................................................30 Kim Ellis – VP Franchise Development, Snip It’s Franchise .............................................................................................................................. 36 -

ROCK 'DO: RESURGENCE of a RESILIENT SOUND in U.S., Fresh Spin Is Put on Format Globally, `No- Nonsense' Music Thrives a Billboard Staff Report

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) ZOb£-L0906 VO H3V38 9N01 V it 3AV W13 047L£ A1N331J9 A1NOW 5811 9Zt Z 005Z£0 100 lllnlririnnrlllnlnllnlnrinrllrinlrrrllrrlrll ZL9 0818 tZ00W3bL£339L080611 906 1I9I0-£ OIE1V taA0ONX8t THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT r MARCH 6, 1999 ROCK 'DO: RESURGENCE OF A RESILIENT SOUND In U.S., Fresh Spin Is Put On Format Globally, `No- Nonsense' Music Thrives A Billboard staff report. with a host of newer acts being pulled A Billboard international staff Yoshida says. in their wake. report. As Yoshida and others look for NEW YORK -In a business in which Likewise, there is no one defining new rock -oriented talent, up -and- nothing breeds like success, "musical sound to be heard Often masquerading coming rock acts such as currently trends" can be born fast and fade among the pack, only as different sub-gen- unsigned three -piece Feed are set- faster. The powerful resurgence of the defining rock vibe res, no-nonsense rock ting the template for intelligent, rock bands in the U.S. market -a and a general feeling continues to thrive in powerful Japanese rock (Global phenomenon evident at retail and that it's OK to make key markets. Music Pulse, Billboard, Feb. 6) with radio, on the charts, and at music noise again. "For the THE FLYS Here, Billboard cor- haunting art rock full of nuances. video outlets -does not fit the proto- last few years, it wasn't respondents take a Less restrained is thrashabilly trio typical mold, however, and shows no cool to say you were in a global sound -check of Guitar Wolf, whose crazed, over -the- signs of diminishing soon. -

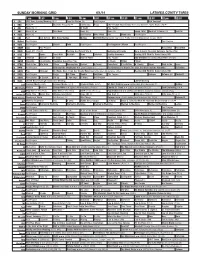

Sunday Morning Grid 6/1/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/1/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Press 2014 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Exped. Wild World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: FedEx 400 Benefiting Autism Speaks. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program The Forgotten Children Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Heart 411 (TVG) Å Painting the Wyland Way 2: Gathering of Friends Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions For You (TVG) 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) El Chavo Fútbol Fútbol 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Walk in the Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Diamond Jo Casino

I don’t know about you, but it has not been Today Chris asked if I could be a pall bearer a banner month in the old Parks household. if needed. At a time when you feel helpless It seems like it’s coming at us from all fronts. to do anything to make it better, an honor Isn’t this Christmas? Shouldn’t we be tiding like this, whether I’m needed or not means a some Yule or decking with some holly bows? lot. It’s not a big thing, but at least you get to This is ridiculous. But I ain’t gonna whine be there for something. In my family, people too long. When the hardest life moments have been there too. hit, you realize how little the other ones are, even when you think those obstacles are go- You may know from past columns that my ing to do you in. But then you face real ad- parents run Toys for Tots in the Tri-States. versity and simply muster the will to trudge Nearly 20,000 toys to who knows how many through the crap to face the big challenges. thousands of kids in Dubuque and surround- I thought about this a while and when I put ing counties. Though he has been the driv- my tired brain to it I realize that we’re get- ing force behind the tremendous growth and ting through it. And the reason is all of those success of the program in Dubuque for the friends around us making it bearable. -

The Beacon, April 10, 2015 Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) Special Collections and University Archives 4-10-2015 The Beacon, April 10, 2015 Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Florida International University, "The Beacon, April 10, 2015" (2015). The Panther Press (formerly The Beacon). 794. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper/794 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Forum for Free Student Expression at Florida International University One copy per person. Additional copies are 25 cents. Vol. 26 Issue 83 fiusm.com Friday, April 10, 2015 POWERFUL PUMPS JASMINE ROMERO/THE BEACON PHOTOS ABOVE BY MEGAN TAIT/THE BEACON LEFT: Walk a Mile in Her Shoes march took place Wednesday, April 8 as up a sign while participating in the Walk in Her Shoes march. Men who part of Take Back the Night Week, organized by the Women’s Center and walked in the march wore heels to symbolize solidarity with women against Interfraternity Council in order to spread awareness on domestic violence, domestic violence, sexual abuse and rape culture. TOP RIGHT: Froylan sexual abuse and to diminish rape culture. BOTTOM RIGHT: Serge Aranov, Remond, a junior studying chemistry, also wears heels during the event on a sophomore studying engineering and brother of Tau Kappa Epsilon holds Wednesday, April 8. -

Collective Soul

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 3, 2008 BOULEVARD CASINO & RIVER ROCK CASINO RESORT PRESENT COLLECTIVE SOUL FRIDAY, MARCH 13 – RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE SATURDAY, MARCH 14 – RIVER ROCK SHOW THEATRE Collective Soul, taken from a line in Ayn Rand's book, “The Fountainhead,” were formed in the small town of Stockbridge, Georgia in the early 90’s by principal songwriter Ed Roland (lead vocals/keyboards/guitars), guitarists Dean Roland and Joel Kosche, rhythm section Will Turpin (bass/percussion) and Shane Evans (drums/percussion). Released in 1993 on the Atlanta indie label Rising Storm, Hints Allegations and Things Left Unsaid proved popular enough on the local level that it was picked up the following year by Atlantic Records. They then released the eponymous sophomore effort which featured the hits "World I Know" and "December" once again going multi- platinum. In 2000, they released Blender which included “Perfect Day,” a duet with Elton John. The group returned to their roots in 2004 releasing the stripped-down and dynamic Youth on its own El Music Group imprint. It was also during this time that they welcomed new guitar player Joel Kosche and drummer Ryan Hoyle. The band’s eighth studio album, Afterwords which was released in 2007 and features the singles "Hollywood” and “All That I Know” is going to be re-released on December 9th to all retail and digital outlets … the album was originally released via exclusive deals with Target and iTunes. The brand new edition includes for the very first time three solo songs by Roland. Currently they have a song titled “Tremble For My Beloved” featured in the new blockbuster film, Twilight as well as on the accompanying chart topping soundtrack. -

PDF (859.55 Kib)

END FEST Mashing and more mashing You are having a beautiful concert- Now I know going experience and listening to one there comes a of your favorite bands play one of your point when favorite songs. It is a comfortable 75 everyone feels degrees. You are feeling good. And then the need to you get kicked in the head by an angst move from ridden 13-year-old male attempting to the front of crowd surf to "Clumsy" by Our Lady the crowd to Peace. EndFest 99 was more than just the back or a festival of anger powered boy bands, . loves the it was undoubtable proof that too many b a n d alterna-teens on one lawn without playing parental supervision is a bad idea. so much Now don't get me wrong. There is that they have nothing wrong with a few underaged to try to get "just a little teens getting together, listening to some closer," but walking around live music and drinking some beer (OK throughout an entire concert is just plain there may be a little something wrong annoying to everyone involved. The with the beer drinking, but this is New best way in which to get from one area EndFest moments: Orleans right?), but there comes a point of the crowd to another is simply to say Above:Collective Soul when even the most laid back former excuse me and then walk past, not to drummer Shane Evans trendy teen has to lay down some rules gets his drink on, right: punch them in the head and then walk Fuel guitarist Carl Bell about behavior while attending a social over their lifeless body. -

G R E E N a Rrow

G G T T HE HE DC G REEN A RROW DC BACK FROM THE DEAD C C OMICS Green Arrow attempted to prevent a terrorist from OMICS THE EMERALD ARCHER detonating a bomb over Metropolis, but gave his life in the process. His lifelong friend, Hal Jordan (formerly Green Lantern II, now a mad being named MIA DEARDEN SAVIOR Oliver OLIVER JONAS QUEEN (GREEN ARROW I) WHILE ON A SOUTH SEA CRUISE, playboy billionaire Oliver E PARALLAX), used his cosmic power to restore Ollie to Mia Dearden ran away from a sent Mia to the E NCYCLOPEDIA FIRST APPEARANCE MORE FUN COMICS #73 (November 1941) Queen was knocked overboard and washed up on Starfish life, but without a soul. violent home when she was a Star City Youth NCYCLOPEDIA STATUS Hero OCCUPATION Adventurer BASE Star City Island. He fashioned a crude bow and arrow and lived like With the help of his “family,” Ollie regained his soul child. Homeless, she turned to Recreational HEIGHT 5ft 11in WEIGHT 185 lbs EYES Green HAIR Blond and made a concerted effort to put his life back in prostitution to support herself. Center for safety. SPECIAL POWERS/ABILITIES Has an excellent eye for archery; trained Robinson Crusoe until he was rescued.A short time later he order. He reconnected with Connor Hawke and Roy She subsequently met the hand-to-hand combatant with above average strength and was rescued and was back on the social scene in his Harper and took in Mia Dearden, a teen from the recently resurrected Oliver Queen. He took her in endurance. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

Helicopter Crash Kills 1

C M Y K www.newssun.com NEWS-SUN Highlands County’s Hometown Newspaper Since 1927 Sunday, December 8, 2013 Volume 94/Number 146 | 75 cents Streaks roll Sebring cruises to win over district foe A Classic Thousands line streets of Lemon Bay Sebring to see annual parade SPORTS, B1 Christmas PHOTOS INSIDE ON A3 PAGE B12 County HELICOPTER CRASH KILLS 1 to study Witness: Crop duster nosed private dived, exploded EMS at sod farm By BARRY FOSTER News-Sun correspondent By SAMANTHA GHOLAR SEBRING – Despite a stri- [email protected] dent stand against even talk- SEBRING — A helicopter ing about the idea of privatiz- reportedly nosed-dived into the ing Highlands County’s ground at a sod farm near the Emergency Medical Services Sebring airport late Friday after- by Commissioner Jim noon, apparently killing the pilot. Brooks, the balance of the No official information had been Highlands County released as of Saturday afternoon, Commission Tuesday agreed but an eyewitness spoke to the to continue investigating the News-Sun Saturday morning near possibility. the scene of the crash site on the Brooks, a former Sod, Citrus and Cane property near Highlands County EMS coor- Sebring International Raceway. dinator himself, said he was The National Transportation not in favor of even entertain- Safety Board was probing the ing the idea. wreckage, which was near an irri- “The coun- gation pond, Saturday morning. ty is respon- Joshua Snell, an employee with sible for pro- the contracting company that helps viding EMS manage the property, said the inci- service. dent occurred around 5:20 p.m. -

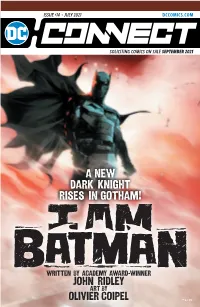

A New Dark Knight Rises in Gotham!

ISSUE #14 • JULY 2021 DCCOMICS.COM SOLICITING COMICS ON SALE SEPTEMBER 2021 A New Dark Knight rises in Gotham! Written by Academy Award-winner JOHN RIDLEY A r t by Olivier Coipel ™ & © DC #14 JULY 2021 / SOLICITING COMICS ON SALE IN SEPTEMBER WHAT’S INSIDE BATMAN: FEAR STATE 1 The epic Fear State event that runs across the Batman titles continues this month. Don’t miss the first issue of I Am Batman written by Academy Award-winner John Ridley with art by Olivier Coipel or the promotionally priced comics for Batman Day 2021 including the Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #1 special edition timed to promote the release of the graphic novel collection. BATMAN VS. BIGBY! A WOLF IN GOTHAM #1 12 The Dark Knight faces off with Bigby Wolf in Batman vs. Bigby! A Wolf in Gotham #1. Worlds will collide in this 6-issue crossover with the world of Fables, written by Bill Willingham with art by Brian Level. Fans of the acclaimed long-running Vertigo series will not want to miss the return of one of the most popular characters from Fabletown. THE SUICIDE SQUAD 21 Interest in the Suicide Squad will be at an all-time high after the release of The Suicide Squad movie written and directed by James Gunn. Be sure to stock up on Suicide Squad: King Shark, which features the breakout character from the film, and Harley Quinn: The Animated Series—The Eat. Bang. Kill Tour, which spins out of the animated series now on HBO Max. COLLECTED EDITIONS 26 The Joker by James Tynion IV and Guillem March, The Other History of the DC Universe by John Ridley and Giuseppe Camuncoli, and Far Sector by N.K. -

CUMULUS MEDIA Unveils PROJECT SHINE Nationwide Appeal to Volunteerism Launches Today Across 422 U.S

CUMULUS MEDIA Unveils PROJECT SHINE Nationwide Appeal to Volunteerism Launches Today Across 422 U.S. Radio Stations and Westwood One Network Platinum-Selling Band Collective Soul Contributes New Version of Anthem “Shine” to Inspire Acts of Humanitarian Service ATLANTA, GA, November 19, 2020 – CUMULUS MEDIA today announces the launch of PROJECT SHINE, a cross-platform charitable initiative, serving as a nationwide call to local volunteerism through partner VolunteerMatch, the world’s largest volunteer engagement network. PROJECT SHINE will be promoted on the company’s 422 radio stations and websites across 87 U.S. markets and through CUMULUS MEDIA’s Westwood One, the largest audio network in the U.S., with creative promos framed by a new version of iconic rock band Collective Soul’s hit “Shine”, re-recorded exclusively for PROJECT SHINE. PROJECT SHINE encourages Cumulus’ hundreds of millions of listeners to visit local station websites to instantly connect with VolunteerMatch’s powerful search engine and database and find local volunteer opportunities. The campaign was produced by Cumulus, with support from production company Benztown and McVay Media. PROJECT SHINE is an evergreen campaign that will inspire local acts of service and human connection in a world that has seen its share of challenges. VolunteerMatch serves over 130,000 participating nonprofits, 150 network partners, and 1.3 million annual website visitors. There are currently 3.2 million volunteers needed by non-profits organizations on VolunteerMatch -- with over 700,000 of those openings for virtual volunteers, and many postings for safely-distanced activities. Brian Philips, EVP, Content & Audience, CUMULUS MEDIA, said: “PROJECT SHINE serves as a conduit for human connection.