Introduction: the Problem of New Media Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Digital Booklet

1 MAIN TITLE 2 THE SMOKING FROG 3 BEDTIME AT BLYE HOUSE 4 NEW CLOTHES FOR QUINT 5 THE CHILDREN'S HOUR 6 PAS DE DEUX 7 LIKE A CHICKEN ON A SPIT 8 ALL THAT PAIN 9 SUMMER ROWING 10 QUINT HAS A KITE 11 PUB PIANO 12 ACT TWO PRELUDE: MYLES IN THE AIR 13 UPSIDE DOWN TURTLE 14 AN ARROW FOR MRS. GROSE 15 FLORA AND MISS JESSEL 16 TEA IN THE TREE 17 THE FLOWER BATH 18 PIG STY 19 MOVING DAY 20 THE BIG SWIM 21 THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS 22 BURNING DOLLS 23 EXIT PETER QUINT, ENTER THE NEW GOVERNESS; RECAPITULATION AND POSTLUDE MUSIC COMPOSED AND CONDUCTED BY JERRY FIELDING WE DISCOVER WHAT When Marlon Brando arrived in THE NIGHTCOMERS had allegedly come HAPPENED TO THE Cambridgeshire, England, during January into being because Michael Winner wanted to of 1971, his career literally hung in the direct “an art film.” Michael Hastings, a well- GARDENER PETER QUINT balance. Deemed uninsurable, too troubled known London playwright, had constructed a and difficult to work with, the actor had run kind of “prequel” to Henry James’ famous novel, AND THE GOVERNESS out of pictures, steam, and advocates. A The Turn of the Screw, which had been filmed couple of months earlier he had informed in 1961, splendidly, as THE INNOCENTS. MARGARET JESSEL author Mario Puzo in a phone conversation In Hastings’ new story, we discover what that he was all washed up, that no one was happened to the gardener Peter Quint and going to hire him again, least of all to play the governess Margaret Jessel: specifically Don Corleone in the upcoming film version how they influenced the two evil children, of Puzo’s runaway best-seller, The Godfather. -

2011-2012 (Pdf)

Trinity College Bulletin Catalog Issue 2011-2012 August 16, 2011 Trinity College 300 Summit Street Hartford, Connecticut 06106-3100 (860)297-2000 www.trincoll.edu Trinity College is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges, Inc NOTICE: The reader should take notice that while every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information provided herein, Trinity College reserves the right to make changes at any time without prior notice. The College provides the information herein solely for the convenience of the reader and, to the extent permissible by law, expressly disclaims any liability that may otherwise be incurred. Trinity College does not discriminate on the basis of age, race, color, religion, gender, sexual orientation, handicap, or national or ethnic origin in the administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other College-administered pro- grams. Information on Trinity College graduation rates, disclosed in compliance with the Student Right- to-Know and Campus Security Act, Public Law 101-542, as amended, may be obtained by writing to the Office of the Registrar, Trinity College, 300 Summit Street, Hartford, CT 06106. In accordance with Connecticut Campus Safety Act 90-259, Trinity College maintains information concerning current security policies and procedures and other relevant statistics. Such information may be obtained from the director of campus safety at (860) 297-2222. Contents College Calendar 7 History of the College 10 The Mission of Trinity College 14 The Curriculum 15 The First-Year Program 16 Special Curricular Opportunities 17 The Individualized Degree Program 28 Graduate Studies 29 Advising 30 Requirements for the Bachelor's Degree 33 Admission to the College 43 College Expenses 49 Financial Aid 53 Key to Course Numbers and Credits 55 Distribution Requirement 57 Interdisciplinary Minors 58 African Studies................................................... -

Photo Journalism, Film and Animation

Syllabus – Photo Journalism, Films and Animation Photo Journalism: Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining. Need and importance, Timeliness The images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events. Objectivity The situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone. Narrative The images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to audiences. Like a writer, a photojournalist is a reporter, but he or she must often make decisions instantly and carry photographic equipment, often while exposed to significant obstacles (e.g., physical danger, weather, crowds, physical access). subject of photo picture sources, Photojournalists are able to enjoy a working environment that gets them out from behind a desk and into the world. -

Festival Fever Sequel Season Fashion Heats Up

arts and entertainment weekly entertainment and arts THE SUMMER SEASON IS FOR MOVIES, MUSIC, FASHION AND LIFE ON THE BEACH sequelmovie multiples season mean more hits festival fever the endless summer and even more music fashionthe hemlines heats rise with up the temps daily.titan 2 BUZZ 05.14.07 TELEVISION VISIONS pg.3 One cancelled in record time and another with a bleak future, Buzz reviewrs take a look at TV show’s future and short lived past. ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR SUMMER MOVIE PREVIEW pg.4 Jickie Torres With sequels in the wings, this summer’s movie line-up is a EXECUTIVE EDITOR force to be reckoned with. Adam Levy DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING Emily Alford SUIT SEASON pg.6 Bathing suit season is upon us. Review runway trends and ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING how you can rock the baordwalk on summer break. Beth Stirnaman PRODUCTION Jickie Torres FESTIVAL FEVER pg.6 ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Summer music festivals are popping up like the summer Sarah Oak, Ailin Buigis temps. Take a look at what’s on the horizon during the The Daily Titan 714.278.3373 summer months. The Buzz Editorial 714.278.5426 [email protected] Editorial Fax 714.278.4473 The Buzz Advertising 714.278.3373 [email protected] Advertising Fax 714.278.2702 The Buzz , a student publication, is a supplemental insert for the Cal State Fullerton Daily Titan. It is printed every Thursday. The Daily Titan operates independently of Associated Students, College of Communications, CSUF administration and the WHAT’S THE BUZZ p.7 CSU system. The Daily Titan has functioned as a public forum since inception. -

![[Michael] Winner Luc Chaput](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6245/michael-winner-luc-chaput-206245.webp)

[Michael] Winner Luc Chaput

Document generated on 09/30/2021 3:14 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma [Gerry] Anderson ... [Michael] Winner Luc Chaput Number 283, March–April 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/68696ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Chaput, L. (2013). [Gerry] Anderson ... [Michael] Winner. Séquences, (283), 20–21. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 20 PANORAMIQUE | Salut l'artiste [GERRY] ANDERSON ... [MICHAEL] WINNER Gerry Anderson | 1929-2012 photographie, et le mari de la comédienne Stefan Kudelski | 1929-2013 Né Gerald Alexander Abrahams, réalisa- Luce Guilbeault. Ingénieur suisse d’origine polonaise, inven- teur et producteur britannique qui, avec teur du magnétophone Nagra (il enregistrera son épouse Sylvia Thamm, créa la télésé- Harry Carey, Jr. | 1921-2012 en polonais) et de ses multiples versions rie culte Thunderbirds (Les Sentinelles de l’air). Fils d’un acteur qui était un grand ami pour lequel il reçut quatre Oscars et la mé- de John Ford, il prit part à plus de cent daille d’honneur John Grierson de la SMPTE. -

The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM

Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM ISSN 1554-6985 VOLUME XI · (/current) NUMBER 2 SPRING 2018 (/previous) EDITED BY (/about) Christy Desmet and Sujata (/archive) Iyengar CONTENTS On Gottfried Keller's A Village Romeo and Juliet and Shakespeare Adaptation in General (/783959/show) Balz Engler (pdf) (/783959/pdf) "To build or not to build": LEGO® Shakespeare™ Sarah Hatchuel and the Question of Creativity (/783948/show) (pdf) and Nathalie (/783948/pdf) Vienne-Guerrin The New Hamlet and the New Woman: A Shakespearean Mashup in 1902 (/783863/show) (pdf) Jonathan Burton (/783863/pdf) Translation and Influence: Dorothea Tieck's Translations of Shakespeare (/783932/show) (pdf) Christian Smith (/783932/pdf) Hamlet's Road from Damascus: Potent Fathers, Slain Yousef Awad and Ghosts, and Rejuvenated Sons (/783922/show) (pdf) Barkuzar Dubbati (/783922/pdf) http://borrowers.uga.edu/7168/toc Page 1 of 2 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM Vortigern in and out of the Closet (/783930/show) Jeffrey Kahan (pdf) (/783930/pdf) "Now 'mongst this flock of drunkards": Drunk Shakespeare's Polytemporal Theater (/783933/show) Jennifer Holl (pdf) (/783933/pdf) A PPROPRIATION IN PERFORMANCE Taking the Measure of One's Suppositions, One Step Regina Buccola at a Time (/783924/show) (pdf) (/783924/pdf) S HAKESPEARE APPS Review of Stratford Shakespeare Festival Behind the M. G. Aune Scenes (/783860/show) (pdf) (/783860/pdf) B OOK REVIEW Review of Nutshell, by Ian McEwan -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

A Filmmakers' Guide to Distribution and Exhibition

A Filmmakers’ Guide to Distribution and Exhibition A Filmmakers’ Guide to Distribution and Exhibition Written by Jane Giles ABOUT THIS GUIDE 2 Jane Giles is a film programmer and writer INTRODUCTION 3 Edited by Pippa Eldridge and Julia Voss SALES AGENTS 10 Exhibition Development Unit, bfi FESTIVALS 13 THEATRIC RELEASING: SHORTS 18 We would like to thank the following people for their THEATRIC RELEASING: FEATURES 27 contribution to this guide: PLANNING A CINEMA RELEASE 32 NON-THEATRIC RELEASING 40 Newton Aduaka, Karen Alexander/bfi, Clare Binns/Zoo VIDEO Cinemas, Marc Boothe/Nubian Tales, Paul Brett/bfi, 42 Stephen Brown/Steam, Pamela Casey/Atom Films, Chris TELEVISION 44 Chandler/Film Council, Ben Cook/Lux Distribution, INTERNET 47 Emma Davie, Douglas Davis/Atom Films, CASE STUDIES 52 Jim Dempster/bfi, Catharine Des Forges/bfi, Alnoor GLOSSARY 60 Dewshi, Simon Duffy/bfi, Gavin Emerson, Alexandra FESTIVAL & EVENTS CALENDAR 62 Finlay/Channel 4, John Flahive/bfi, Nicki Foster/ CONTACTS 64 McDonald & Rutter, Satwant Gill/British Council, INDEX 76 Gwydion Griffiths/S4C, Liz Harkman/Film Council, Tony Jones/City Screen, Tinge Krishnan/Disruptive Element Films, Luned Moredis/Sgrîn, Méabh O’Donovan/Short CONTENTS Circuit, Kate Ogborn, Nicola Pierson/Edinburgh BOXED INFORMATION: HOW TO APPROACH THE INDUSTRY 4 International Film Festival, Lisa Marie Russo, Erich BEST ADVICE FROM INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS 5 Sargeant/bfi, Cary Sawney/bfi, Rita Smith, Heather MATERIAL REQUIREMENTS 5 Stewart/bfi, John Stewart/Oil Factory, Gary DEALS & CONTRACTS 8 Thomas/Arts Council of England, Peter Todd/bfi, Zoë SHORT FILM BUREAU 11 Walton, Laurel Warbrick-Keay/bfi, Sheila Whitaker/ LONDON & EDINBURGH 16 article27, Christine Whitehouse/bfi BLACK & ASIAN FILMS 17 SHORT CIRCUIT 19 Z00 CINEMAS 20 The editors have made every endeavour to ensure the BRITISH BOARD OF FILM CLASSIFICATION 21 information in this guide is correct at the time of GOOD FILMS GOOD PROGRAMMING 22 going to press. -

Media Arts Design 1

Media Arts Design 1 • Storyboarding Certificate (https://catalog.nocccd.edu/cypress- MEDIA ARTS DESIGN college/degrees-certificates/media-arts-design/storyboarding- certificate/) Division: Fine Arts Courses Division Dean MAD 100 C Introduction to Media Arts Design 3 Units Dr. Katy Realista Term hours: 36 lecture and 72 laboratory. This course focuses on the use of digital design, video, animation and page layout programs. This course Faculty is designed for artists to design, create, manipulate and export graphic Katalin Angelov imagery including print, video and motion design elements. This course is Edward Giardina intended as a gateway into the varied offerings of the Media Arts Design program, where the student can pursue more in-depth study on the topic(s) Counselors that most attracted them during this introductory class. $20 materials fee payable at registration. (CSU, C-ID: ARTS 250) Renay Laguana-Ferinac MAD 102 C Introduction to WEB Design (formerly Introduction to WEB Renee Ssensalo Graphics-Mac) 3 Units Term hours: 36 lecture and 72 laboratory. This course is an overview of the Degrees and Certificates many uses of media arts design, with an emphasis on web publishing for • 2D Animation Certificate (https://catalog.nocccd.edu/cypress- the Internet. In the course of the semester, students create a personal web college/degrees-certificates/media-arts-design/associate-in-science- page enriched with such audiovisual elements as animation, sound, video in-film-television-and-electronic-media-for-transfer-degree/) and different types of still images. This course is intended as a gateway into • 3D Animation Certificate (https://catalog.nocccd.edu/cypress- the varied offerings of the Media Arts Design program, where the student college/degrees-certificates/media-arts-design/3d-animation- can pursue more in-depth study on the topics that most attracted them certificate/) during this introductory class. -

How to Choose a Search Engine Or Directory

How to Choose a Search Engine or Directory Fields & File Types If you want to search for... Choose... Audio/Music AllTheWeb | AltaVista | Dogpile | Fazzle | FindSounds.com | Lycos Music Downloads | Lycos Multimedia Search | Singingfish Date last modified AllTheWeb Advanced Search | AltaVista Advanced Web Search | Exalead Advanced Search | Google Advanced Search | HotBot Advanced Search | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Domain/Site/URL AllTheWeb Advanced Search | AltaVista Advanced Web Search | AOL Advanced Search | Google Advanced Search | Lycos Advanced Search | MSN Search Search Builder | SearchEdu.com | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search File Format AllTheWeb Advanced Web Search | AltaVista Advanced Web Search | AOL Advanced Search | Exalead Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Geographic location Exalead Advanced Search | HotBot Advanced Search | Lycos Advanced Search | MSN Search Search Builder | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Images AllTheWeb | AltaVista | The Amazing Picture Machine | Ditto | Dogpile | Fazzle | Google Image Search | IceRocket | Ixquick | Mamma | Picsearch Language AllTheWeb Advanced Web Search | AOL Advanced Search | Exalead Advanced Search | Google Language Tools | HotBot Advanced Search | iBoogie Advanced Web Search | Lycos Advanced Search | MSN Search Search Builder | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Multimedia & video All TheWeb | AltaVista | Dogpile | Fazzle | IceRocket | Singingfish | Yahoo Video Search Page Title/URL AOL Advanced -

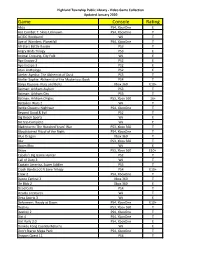

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

MPEG-7-Aligned Spatiotemporal Video Annotation and Scene

MPEG-7-Aligned Spatiotemporal Video Annotation and Scene Interpretation via an Ontological Framework for Intelligent Applications in Medical Image Sequence and Video Analysis by Leslie Frank Sikos Thesis Submitted to Flinders University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Science and Engineering 5 March 2018 Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................ VI List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. VIII List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. IX List of Listings .................................................................................................................................. X Declaration .................................................................................................................................... XII Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... XIII Chapter 1 Introduction and Motivation ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Limitations of Video Metadata.............................................................................................. 1 1.2 The Limitations of Feature Descriptors: the Semantic Gap .....................................................