Rural Poverty in Romania and the Need for Diversification: Carpathian Studies Turnock, David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

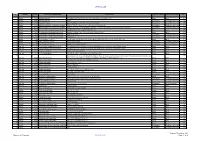

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Medici Veterinari De Libera Practica Buzau

AUTORITATEA NAŢIONALĂ SANITARĂ VETERINARĂ ŞI PENTRU SIGURANŢA ALIMENTELOR DIRECŢIA SANITARĂ VETERINARĂ ŞI PENTRU SIGURANŢA ALIMENTELOR BUZĂU DATELE DE CONTACT ALE MEDICILOR VETERINARI DE LIBERĂ PRACTICĂ ABILITAȚI CU ACTIVITATEA DE IDENTIFICARE ȘI ÎNREGISTRARE A ANIMALELOR Nr. Localitatea Denumirea societății Numele medicului veterinar Telefon contact crt. 1 Amaru S.C VLAMIVET ANIMAL CARE BOANCA IONUT 0745005662 2 Balaceanu SC VET CLASS MINTOIU CIPRIAN 0722485922 3 Balta Alba SC BIOSS SETUP STANCIU C-TIN 0723644286 4 Beceni SC POLO VET HOSTINAR SILVIU 0741253594 5 Berca SC ROFARMVET TUDOSIE DOINA 0740144922 6 Bisoca SC COLIVET COMANESCU GEORGICA 0745005652 7 Blajani CMVI SAMPETRU DECEBAL SANPETRU DECEBAL 0751049907 8 Boldu SC FLOREA VET 99 SRL FLOREA VASILE 0748213746 9 Bozioru SC YANA VET POPA TATIANA 0723259597 10 Bradeanu SC MAXIVET FARMING SRL PINGHEL STEFAN ROMICA 0735553667 11 Braesti SC DIAMOND VET MERCAN STEFAN 0749072505 12 Breaza SC MARIUCA & DAVID CIOBANU OVIDIU NICUSOR 0722971808 13 Buda SC ZOOVET IBRAC LEONTINA 0726329778 14 Buzau SC SALVAVET TABACARU VASILE 0722221552 15 C. A. Rosetti RO FARMAVET SRL CRETU MARIN 0729840688 16 Canesti CMVI GHERMAN SIMONA GHERMAN SIMONA 0745108469 17 Caragele SC CORNEX 2000 SRL CARBUNARU ADRIAN 0722565985 18 Catina CMVI VOROVENCI ALIN VOROVENCI ALIN 0740254305 19 Cernatesti SC VETERINAR SERVICE BRATU GEORGE Pagina 1 din 4 Adresa: Municipiul Buzău, strada Horticolei, nr. 58 bis, Cod Poştal 120081; Telefon: 0238725001, 0758097100, Fax: 0238725003 E-mail: [email protected] , Web: http://www.ansvsa.ro/?pag=565&jud=Buzau -

Indicatori Fizici

"PROIECTUL REGIONAL DE DEZVOLTARE A INFRASTRUCTURII DE APA SI APA UZATA DIN JUDETUL BUZAU, IN PERIOADA 2014-2020" Tabel 1 Indicatorii fizici aferenti sistemului de alimentare cu apa din localitatile impactate de proiect* Cantitate / (UAT) Nr. ID Descriere U.M. UAT TOTAL Crt. POIM CJ UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT Valea UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT Ramnicu Buzau** Buzau Nehoiu Patarlagele Magura Ramnicului Topliceni Grebanu Cislau Cernatesti Merei Viperesti Manzalesti Lopatari Calvini Chiojdu Puiesti Sarat SISTEM DE ALIMENTARE CU APA 1 - Foraje noi buc 27 20 - - 10 - - - - - - - - 57 - - - - - 2 - Reabilitare foraje buc - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - - 1 - - - 3 - Extindere si reabilitare captare cu dren buc - - - - - - 1 - - - - - - 1 - - - - - Reabilitare captare de suprafata / 4 - buc 1 - - - - - - - - - - - 1 - 2 Reabilitare desnisipator - - - - Conducta de aductiune/transport/legatura 5 2S72 m 1,104 4,379 18,307 212 10,979 10,915 - 1,297 - - - - 8,440 103,137 noua 47,504 - - - - 6 2S73 Conducta de aductiune - reabilitare m 692 11,842 3,876 - - - - 295 - - - - - - 16,705 - - - - Conducte de descarcare in 7 - m - 3,508 - - - - - - - - - - - 3,508 emisar/evacuare apa spalare - - - - - 8 2S78 Statie de clorinare noua buc 6 1 3 - 1 - 2 3 - 1 - - - - 1 18 - - - 9 2S78 Statie de tratare noua buc 1 1 - - - - - - - - - - - 2 - - - - - 10 2S78 Statie de tratare - reabilitare si extindere buc 1 - - - 1 - - - - - - - 1 - 3 - - - - 11 - Statie de pompare noua buc 4 - 2 6 6 - 3 7 2 - 1 2 - 5 6 1 45 - - 12 - Statie de pompare - reabilitare buc -

Ministerul Sănătăţii Informare Privind Centrele De Permanenta Care Au Functionat in Judetul Buzau

MINISTERUL SĂNĂTĂŢII DIRECTIA DE SĂNĂTATE PUBLICĂ A JUDEŢULUI BUZĂU Str. Stadionului nr.7. SE APROBA, Tel./fax: 0238-710.860 DIRECTOR EXECUTIV, E-mail: [email protected] DR.ACSINTE VENERA INFORMARE PRIVIND CENTRELE DE PERMANENTA CARE AU FUNCTIONAT IN JUDETUL BUZAU Conform prevederilor Ordinului MSF nr.151/2002 pentru aprobarea Regulamentului privind Organizarea si Functionarea Centrelor de Permanenta in Asistenta Primara si a HGR nr.1521/2002 pentru aprobarea Contractului Cadru privind Conditiile Acordarii Asistentei Medicale Primare in cadrul Sistemului de Asigurari Sociale de Sanatate in Asistenta Medicala Primara in Judetul Buzau- DIRECTIA DE SANATATE PUBLICA a dispus infiintarea, incepand cu 01.09.2003- a 8 centre de permanenta , cu urmatoarea locatie: 1.Centrul de Permanenta Buzau -Ambulatoriu de Specialitate al Spitalului Judetean Buzau -63 Medici de Familie 2. Centrul de Permanenta Rm.Sarat -Statia de Ambulanta Rm.Sarat -19 Medici de familie 3. Centrul de Permanenta Boldu -Dispensarul Medical Boldu- Comuna Boldu -Teritoriu deservit- Valcelele, Balta Alba, Boldu, Ghergheasa, Ramnicelu -6 Medici de Familie 4. Centrul de Permanenta Smeeni -Spitalul Smeeni- Comuna Smeeni -Teritoriu deservit- Smeeni, Gheraseni, Bradeanu,Tintesti 5. Centrul de Permanenta Sageata -Punctul Sanitar Gavanesti-Comuna Sageata -Teritoriu deservit- Sageata, Vadu-Pasii, Robeasca -7 Medici de familie 6. Centrul de Permanenta Cilibia -Dispensarul Medical Cilibia-Comuna Cilibia -Teritoriu deservit- Galbinasi,Cilibia,C.A.Rosetti,Rusetu,Luciu,Largu -6 Medici de Famnilie 7. Centrul de Permanenta Patarlagele -Centrul de Sanatate Patarlagele- Comuna Patarlagele MINISTERUL SĂNĂTĂŢII DIRECTIA DE SĂNĂTATE PUBLICĂ A JUDEŢULUI BUZĂU Str. Stadionului nr.7. SE APROBA, Tel./fax: 0238-710.860 DIRECTOR EXECUTIV, E-mail: [email protected] DR.ACSINTE VENERA -Teritoriu deservit- Buda-Craciunesti, Clavini, Catina, Panatau, Patarlagele,Viperesti, Colti 8. -

Colecţia De Planuri

ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE DIRECŢIA JUDEŢEANĂ BUZĂU A ARHIVELOR NAŢIONALE INVENTAR COLECŢIA DE PLANURI SJAN Buzau 680 u.a. 45 pag. Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei 1 COLECŢIA PLANURI Prefaţă inventar Colecţia de planuri conţine un număr de 681 documente de acest gen, documente care redau unele situaţii şi stări de lucruri geo-fizice, politice, militare, administrative, funciare, silvice, de proiectare şi construcţie pentru diferiţi ani sau momente istorice. Planurile, care numeric sunt preponderente în colecţie, privesc judeţul Buzău, şi oraşul Buzău în primul rând. Cele mai numeroase sunt planurile de moşii situate în judeţul Buzău, întocmite la sfârşitul secolului al XIX lea şi în primele decenii ale secolului al XX lea, pentru rezolvarea unor succesiuni, vânzări-cumpărări, delimitări, încălcări de proprietăţi. Dintre planurile de moşii menţionăm proprietăţile statului de la Buzău, Amara, Rm. Sărat şi ale moşiilor ce aparţin unor mari proprietari precum Lascăr Catargiu, Maria Lucasievici, A. Popovici. Alte planuri prezintă delimitarea moşiilor în loturi cedate locuitorilor în urma reformei agrare de la 1921. colecţia mai cuprinde şi schiţe, planuri de construcţie pentru diferite instituţii publice precum Liceul Comercial Rm. Sărat, Şcoala Normală de fete Buzău, Biserica Buna Vestire. De asemenea, informaţii cu caracter statistic se găsesc în planul cu situaţia demografică a fostului judeţ Rm. Sărat din anul 1941. Astfel, aceste documente furnizează, în urma studierii lor, informaţii preţioase asupra evoluţiei administrativ-teritoriale, demografice şi nu în ultimul rând economice ale judeţului Buzău. Inventarul colecţiei a fost completat de d-na Manole Liliana. Întocmit, Insp. sup. Bulfan Cătălina SJAN Buzau Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei 2 INVENTAR AL COLECŢIEI DE PLANURI Nr. -

Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) in Some Riparian Ecosystems of South-Eastern Romania

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 30 Décembre Vol. LIV (2) pp. 409–423 «Grigore Antipa» 2011 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-011-0026-y CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE KNOWLEDGE ON STAPHYLINIDS (COLEOPTERA: STAPHYLINIDAE) IN SOME RIPARIAN ECOSYSTEMS OF SOUTH-EASTERN ROMANIA MELANIA STAN Abstract. The diversity of the staphylinid fauna is investigated in some riparian ecosystems along rivers of south-east Romania: the Danube, Prut, Siret, Buzău. 94 staphylinid species and subspecies were identified from 23 investigated sites. Thecturota marchii (Dodero) is a new record for the Romanian fauna. Leptobium dimidiatum (Grideli), a rare species, is recorded from a new site, the second record from Romania. Résumé. On présente la diversité de la faune de staphylinides dans quelques écosystèmes ripariens qui se trouvent le long des rivières du sud-est de la Roumanie: Danube, Prut, Siret, Buzău. 94 espèces et sous-espèces de staphylinides y ont été trouvées, en 23 sites. Theucturota marchii (Dodero) est signalée pour la première fois en Roumanie. Leptobium dimidiatum (Grideli), une espèce rare, est signalée dans un nouveau site, le deuxième sur le territoire roumain. Pour chaque espèce on présente le site où elle a été trouvée, la date, la nombre d’exemplaires (pour la plupart le sexe), legit. Sur la base des observations faites sur le terrain on offre une brève référence sur la caractéristique écologique des espèces. Key words: Staphylinidae, riparian ecosystems, faunistics. INTRODUCTION The hydrobiologic regime represents the most important control element for the existence, characteristics and maintaining of the wetland types and of their characteristic processes. Riparian areas are very important for the delimitation of the ecosystems, but especially in the specific functions which they have within the ecosystem complexes: flooding control, protection against erosion, supplying/ discharging of the underground waters, nutrient retention, biomass export, protection against storms, water transportation, stabilization of the microclimate. -

Buzău 651 MONITORUL OFICIALALROMÂNIEI,PARTEAI,Nr.670Bis/1.X.2010

MINISTERUL CULTURII ŞI PATRIMONIULUI NAŢIONAL LISTA MONUMENTELOR ISTORICE 2010 Judeţul Buzău MONITORUL OFICIALALROMÂNIEI,PARTEAI,Nr.670bis/1.X.2010 651 Nr. crt. Cod LMI 2004 Denumire Localitate Adresă Datare 1 BZ-I-s-B-02189 Situl arheologic din parcul Crâng municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng 2 BZ-I-m-B-02189.01 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng, 0,4 km SV de sec. VI - VII, Epoca castelul de apă medievală timpurie, Cultura Ipoteşti - Cândeşti 3 BZ-I-m-B-02189.02 Necropolă municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng, între sere şi mil. III - II, Epoca Obelisc bronzului mijlociu, Cultura Monteoru 4 BZ-I-m-B-02189.03 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng, zona sere mil. IV, Eneolitic, Obelisc,spre poarta mare a Cultura Gumelniţa Crângului 5 BZ-I-s-B-02190 SitularheologicdelaBuzău municipiul BUZĂU BuzăuE,la2kmdestaţia Buzău Sud 6 BZ-I-m-B-02190.01 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU BuzăuE,la2kmdestaţia Buzău sec. XVII - XVIII, Sud Cultura Sântana de Mureş - Cerneahov 7 BZ-I-m-B-02190.02 Necropolă municipiul BUZĂU BuzăuE,la2kmdestaţia Buzău sec. XVII - XVIII Sud 8 BZ-I-m-B-02190.03 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU La cca 1 km SE de Cimitirul sec. IV - V p. Chr., evreiesc, spre Pădurea Frasinu; Epoca migraţiilor târzie cca 2 km S de staţia BuzăuSud MINISTERUL CULTURII ŞI PATRIMONIULUI NAŢIONAL INSTITUTUL NAŢIONAL AL PATRIMONIULUI 652 MONITORULOFICIALALROMÂNIEI,PARTEAI,Nr.670bis/1.X.2010 Nr. crt. Cod LMI 2004 Denumire Localitate Adresă Datare 9 BZ-I-s-B-02191 Situl arheologic de la Buzău, punct "Dispensar" municipiul BUZĂU Str. Bucegi în zona Dispensarului nr. 3, până în incinta Centrului Militar şia Liceului de Arte 10 BZ-I-m-B-02191.01 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU Str. -

Summative Evaluation of “First Priority: No More ‘Invisible’ Children!” Evaluation Report

MINISTRY OF LABOR AND SOCIAL JUSTICE for every child National Authority for the Protection of Child′s Rights and Adoption Summative evaluation of “First priority: no more ‘invisible’ children!” Evaluation report International Consulting Expertise Initiative • Commitment • Energy MINISTRY OF LABOR AND SOCIAL JUSTICE for every child National Authority for the Protection of Child′s Rights and Adoption Summative evaluation of “First priority: no more ‘invisible’ children!” Evaluation report Contracting Agency and Beneficiary: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Romania Country Office Contractor: International Consulting Expertise in consortium with Camino Association Evaluation Coordinators (UNICEF): Viorica Ștefănescu, Voichița Tomuș, Alexandra Grigorescu Boțan Evaluation Team Members: Project Manager Alina-Maria Uricec Gabriela Tănase Team leader Irina Lonean Evaluation Experts Liliana Roșu Adriana Blănaru Alina Bîrsan Anda Mihăescu Ecaterina Stativă Oana Clocotici International Consulting Expertise Initiative • Commitment • Energy Bucharest 2017 SUMMATIVE EVALUATION OF “FIRST PRIORITY: NO MORE ‘INVISIBLE’ CHILDREN!” Contents List of tables .......................................................................................................................................VII List of figures ...................................................................................................................................... IX Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................ -

Buletin Informativ Statistic

AGENTIA JUDETEANA PENTRU OCUPAREA Agentia Judeteana pentru Ocuparea Fortei de Munca Buzau FORTEI DE MUNCA BUZAU * Sediul central – Buzau, str. Ion Baiesu, bl. 3A, parter, Tel. (+40238)713216, (+40238)720290, Fax (+40238)713216, E-mail: [email protected]; www.ajofmbuzau.ro Organizare in teritoriu: Agentia Locala pentru Ocuparea Fortei de Munca Buzau * Buzau, str. Unirii, Bl. 11 D-E, parter Tel. (+40238)720229, (+40238)710257; * Buzau, str. Pacii, nr. 29 Tel. (+40238)720287, (+40238)722540 - EURES; Punct de lucru Rimnicu Sarat * Rm.Sarat, str. Plt Torcaru, nr. 12 bis Tel./fax (+40238)562855; Punct de lucru Pogoanele * Pogoanele, str. Libertatii, Bl. 4, parter Tel./fax (+40238)552361; Punct de lucru Nehoiu * Nehoiu, str. Mihai Viteazul, nr. 3 bis, Bl. 30/31, parter Tel./fax (+40238)554545; Centrul de Formare Profesionala a Adultilor * Buzau, str. Pacii, Nr. 29 Buzau, 31 iulie 2021 Tel. (+40238)727913, Fax (+40238)727913; A.J.O.F.M. BUZAU BALANTA SOMAJULUI ********************************** INTRARI IN PLATA SI EVIDENTA IESIRI DIN PLATA SI EVIDENTA MODIFICARI RATA SOLD Intrari REPUNERI abs. fata SOMAJ LUNA / ANUL TOTAL Intrari din Intrari SOMERI Expirare SUSP. S. I. FINAL SOLD INITIAL absolventi Sold suspend TOTAL IESIRI Incadrati Pensionati Alte cauze de per. ULUI INTRARI cimpul muncii neindemnizati INDEMNIZ. perioada INCADRARE indemnizati ant.(+/-) TOTAL AN 2005 12988 48185 4846 1292 40334 2385 (-)672 46729 5615 29160 212 10029 1713 (+)1947 14444 7,4 TOTAL AN 2006 14444 37654 4039 870 31245 1647 (-)532 37475 4166 24377 156 7661 1115 (+)870 -

Farmaciile Aflate in Contract Cu Cjas Buzau La Data De 14.06.2019

FARMACIILE AFLATE IN CONTRACT CU CJAS BUZAU LA DATA DE 14.06.2019 Denumire farmacie Nr.Contract Adresa Program Nr.crt. Telefon E-Mail Luni Marţi Miercuri Joi Vineri Sâmbătă Duminică 2M Pharma 1 84 Vadu Pasii,Complex Prestari Servicii tel.0238/588.455 [email protected] 09:00-17:00 09:00-17:00 09:00-17:00 09:00-17:00 09:00-17:00 Inchis Inchis 2 Abc Farm SRL 6 Buzau, Bulevardul Republicii,Nr.4A,Zona Spitalului CFRtel.0238/712228 [email protected] 09.00-13.00 15.00-19-0009.00-13.00 15.00-19-009.00-13.00 15.00-19-0009.00-13.00 15.00-19-0009.00-13.00 15.00-19-0009.00-13.00 09.00-13.00 3 Adivo Farm SRL 13 Rm.Sarat Str.Patriei , Bl.9E+F , Parter tel.0238/569890 [email protected] 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 Inchis 4 Adonis Pharm SRL 157 Lopatari tel.0238526256 [email protected] 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 09.00-17.00 Inchis Inchis 5 Alina Pharm SRL 94 Alina Pharm Cislau Cislau,Str.Calea Mihai Viteazu Nr.180 tel.0238/551455 [email protected] 08:30-17:30 08:30-17:30 08:30-17:30 08:30-17:30 08:30-17:30 08:30-12:30 Inchis Alina Pharm Merei Sat Merei,Com.Merei,Str.Principala,Nr.430 tel.0238/509273 [email protected] 08:00-15:30 08:00-15:30 08:00-15:30 08:00-15:30 08:00-15:30 08:30-12:00 Inchis Alina Pharm Unguriu Sat Unguriu,Com.Unguriu,Str.Brasovului,Nr.119 tel.0741606676 [email protected] 08:00-13:00 13:30-16:00 08:00-16:00 08:00-16:00 08:00-16:00 Inchis Inchis Alina Pharm Viperesti Sat. -

Statistical Tools in Landscape Archaeology 1

Archeologia e Calcolatori 21, 2010, 339-356 STATISTICAL TOOLS IN LANDSCAPE ARCHAEOLOGY 1. Introduction Recent evolution of the Romanian national policy regarding the pro- tection of cultural heritage has increased the general interest in organizing information about archaeological sites and monuments in georeferenced databases. The main result of this systematization was aimed at monitoring the interaction between archaeological heritage and urban development. However, a better use of these data management systems through Archaeo- logical Predictive Modeling could contribute both to the improvement of the heritage management activity and to an advance in scienti�c research. Our aim here is to discuss the intermediate process, which should ensure the transition from tables and lists of archaeological discoveries to meaningful connections and interactions, using Landscape Archaeology methods and statistical algorithms. As GIS applications in archaeology were classi�ed by Aldenderfer (1992) and Kvamme (1999), Archaeological Predictive Models (APMs) rep- resent an important evolution of spatial integrated databases of archaeologi- cal records. Most of the development of these techniques has taken place in North American archaeology, where the spatial extent of some archaeological landscapes was dif�cult to survey in an inclusive and ef�cient manner. Re- cently, APMs were also applied in the national management of archaeological resources of some European countries, in particular the Netherlands (van Leusen, Kamermans 2005; Verhagen 2007; Kamermans, Van Leusen, Verhagen 2009), and Great Britain (Renfrew, Bahn 2004). APM correlates the distribution and density of certain categories of archaeological sites discovered in a particular geographic region with the environmental conditions of their location and surroundings. Therefore, it predicts with a variable probability the location of analogous sites by identifying similar environmental conditions with those quanti�ed for the discoveries already known. -

37. Palatul Copiilor Buzău Şi Filialele Rîmnicu Sărat, Pătârlagele, Nehoiu, Berca, Beceni, Pogoanele

INSPECTORATUL ŞCOLAR JUDEŢEAN BUZĂU ________________________________________________________________________ 37. PALATUL COPIILOR BUZĂU ŞI FILIALELE RÎMNICU SĂRAT, PĂTÂRLAGELE, NEHOIU, BERCA, BECENI, POGOANELE PROIECTARE-ORGANIZARE - Strategiile de coordonare şi direcţiile de dezvoltare ale activităţii din Palatul Copiilor Buzău şi din cele sase filiale din judeţ s-au regăsit în planurile echipelor manageriale ale instituţiilor ce şi-au articulat dimensiunile educaţionale cu cele prevăzute în documentele de lucru ale Inspectoratului Şcolar Judeţean Buzău şi ale Ministerul Educaţiei; - Există o reţea coerentă de coordonare a activităţii educative: a) la nivel judeţean – IŞJ Buzău, prin inspectorul de specialitate; b) la nivelul instituţiilor noastre, fiecare unitate şcolară şi-a proiectat un program specific al activităţilor, urmărind dezvoltarea programelor naţionale şi o ofertă proprie de activităţi, în raport cu specificul zonei şi al orizontului de interes al elevilor, părinţilor. În anul şcolar 2020-2021, oferta educaţională, este variată; OFERTA EDUCAŢIONALĂ PENTRU ANUL ŞCOLAR 2020-2021 Palatul Copiilor Buzău – cercurile de: informatică, design vestimentar, arte plastic-pictură, aeromodele, carting-automodele, şah, cultură şi civilizaţie engleză, teatru, tenis de câmp, cenaclu literar, redacţie de presă/radio-tv, muzică populară, muzică uşoară, cor-grup vocal, dans modern, dans popular, electrotehnică, prietenii pompierilor; Clubul Copiilor Râmnicu Sărat – cercurile: coregrafie – balet, carting, muzică vocal-instrumentală, electronică,