The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

1 2014 OSCE HUMAN DIMENSION IMPLEMENTATION MEETING September 22 - October 3, 2014 Written contribution of The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) Within the framework of their joint programme, The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Under Working session 3: Fundamental freedoms I (continued), including freedom of peaceful assembly and association September 23, 2014 2 The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of their joint programme, the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, wish to draw the attention of the Organisation for the Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) on the ongoing threats and obstacles faced by human rights defenders in OSCE Participating States. In 2013 and 2014, human rights defenders in Eastern Europe and Central Asia continued to operate in a difficult, and sometimes hostile environment. The situation particularly deteriorated in Azerbaijan, Hungary, Kyrgyzstan, and the Russian Federation, where the civil society has continued to face acts of reprisals by the authorities and where domestic legal frameworks and practices governing the exercise of the right to freedoms of assembly and association were drastically restricted. In other countries, human rights defenders have continued to be subjected to arbitrary detention following blatantly unfair trials, in particular in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, or to lengthy pre-trial detention, -

SITUATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in BELARUS in 2014

Human Rights Centre “Viasna” SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS in BELARUS in 2014 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Minsk, 2015 SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN BELARUS in 2014 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Author and compiler: Tatsiana Reviaka Editor and author of the foreword: Valiantsin Stefanovich The edition was prepared on the basis of reviews of human rights violations in Belarus published every month in 2014. Each of the monthly reviews includes an analysis of the most important events infl uencing the observance of human rights and outlines the most eloquent and characteristic facts of human rights abuses registered over the described period. The review was prepared on the basis of personal appeals of victims of human rights abuses and the facts which were either registered by human rights activists or reported by open informational sources. The book features photos from the archive of the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, as well as from publications on the websites of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty Belarus service, the Nasha Niva newspaper, tv.lrytas.lt, baj.by, gazetaby.com, and taken by Franak Viachorka and Siarhei Hudzilin. Human Rights Situation in 2014: Trends and Evaluation The situation of human rights during 2014 remained consistently poor with a tendency to deterioration at the end of the year. Human rights violations were of both systemic and systematic nature: basic civil and political rights were extremely restricted, there were no systemic changes in the fi eld of human rights (at the legislative level and (or) at the level of practices). The only positive development during the year was the early release of Ales Bialiatski, Chairman of the Human Rights Centre “Viasna” and Vice-President of the International Federation for Human Rights. -

Submission to the Committee Against Torture in Relation to Its Examination of the Fourth Periodic Report of Azerbaijan

Submission to the Committee against Torture in relation to its examination of the fourth periodic Report of Azerbaijan 56th Session of the Committee against Torture 26 October 2015 1 I. Introduction Already in its last Concluding Observations on Azerbaijan in 2009, the Committee against Torture (CAT) recommended that Azerbaijan fully guarantee and protect the right of freedom of opinion and expression of human rights defenders (HRD)1 and introduce legal mechanisms and practical measures to that effect because it was concerned about the harassment of HRD as well as the lack of due process in the criminal convictions of individuals who expressed their opinions.2 Unfortunately, the situation has dramatically worsened since 2009. Starting in 2012, the crackdown of civil society organisations (CSOs) and HRD has intensified. Dozens of political activists and critical journalists have been harassed by restrictive legislation and arbitrary detained and charged with fabricated accusations such as fraud, illegal business, or hooliganism. In unfair trials HRD have been sentenced to long-term imprisonment to punish them for their human rights activities and for raising their voice against a corrupt government. At the same time, Azerbaijan is barely cooperating with international organizations. The United Nations Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture (SPT) had to suspend its visit to Azerbaijan in September 2014 as its delegation was prevented from visiting several places and was barred from completing its work despite repeated attempts.3 Moreover, Azerbaijan has a total of 126 judgments by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) that are awaiting execution. The majority of those judgments are related to the harassment of CSO and HRD. -

Submission to the Committee Against Torture in Relation to Its Examination of the Fourth Periodic Report of Azerbaijan

Submission to the Committee against Torture in relation to its examination of the fourth periodic Report of Azerbaijan 56th Session of the Committee against Torture 26 October 2015 1 I. Introduction Already in its last Concluding Observations on Azerbaijan in 2009, the Committee against Torture (CAT) recommended that Azerbaijan fully guarantee and protect the right of freedom of opinion and expression of human rights defenders (HRD)1 and introduce legal mechanisms and practical measures to that effect because it was concerned about the harassment of HRD as well as the lack of due process in the criminal convictions of individuals who expressed their opinions.2 Unfortunately, the situation has dramatically worsened since 2009. Starting in 2012, the crackdown of civil society organisations (CSOs) and HRD has intensified. Dozens of political activists and critical journalists have been harassed by restrictive legislation and arbitrary detained and charged with fabricated accusations such as fraud, illegal business, or hooliganism. In unfair trials HRD have been sentenced to long-term imprisonment to punish them for their human rights activities and for raising their voice against a corrupt government. At the same time, Azerbaijan is barely cooperating with international organizations. The United Nations Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture (SPT) had to suspend its visit to Azerbaijan in September 2014 as its delegation was prevented from visiting several places and was barred from completing its work despite repeated attempts.3 Moreover, Azerbaijan has a total of 126 judgments by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) that are awaiting execution. The majority of those judgments are related to the harassment of CSO and HRD. -

The Right to Insult in International Law

THE RIGHT TO INSULT IN INTERNATIONAL LAW Amal Clooney and Philippa Webb* ABSTRACT States all over the world are enacting new laws that criminalize insults, and using existing insult laws with renewed vigour. In this article, we examine state practice, treaty provisions, and case law on insulting speech. We conclude that insulting speech is currently insufficiently protected under international law and regulatedby confused case law and commentary. We explain that the three principal internationaltreaties that regulate speech provide conflicting guidance on the right to insult in internationallaw, and the treaty provisions have been interpreted in inconsistent ways by international courts and United Nations bodies. We conclude by recommending that internationallaw should recognize a "rightto insult"and, drawingon US practice under the FirstAmendment, we propose eight recommendations to guide consideration of insulting speech in internationallaw. These recommendations would promote coherence in international legal standards and offer greater protection to freedom of speech. * Amal Clooney is a barrister at Doughty Street Chambers and a Visiting Professor at Columbia Law School. Philippa Webb is a barrister at 20 Essex Street Chambers and Reader (Associate Professor) in Public International Law at King's College London. We thank Matthew Nelson, Anna Bonini, Katarzyna Lasinska, Raphaelle Rafin, Tiffany Chan, Deborah Tang, Ollie Persey, and Mirka Fries for excellent research assistance. We are grateful to Professor Guglielmo Verdirame, Professor Michael Posner, Professor Vince Blasi, and Nani Jansen for comments. COL UMBIA HUMAN RIGHTS LAW RE VIE W [48.2 INTRODUCTION Freedom of speech is under attack. States all over the world are enacting new laws that criminalize insults and are using existing insult laws with renewed vigour. -

Final-Signatory List-Democracy Letter-23-06-2020.Xlsx

Signatories by Surname Name Affiliation Country Davood Moradian General Director, Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies Afghanistan Rexhep Meidani Former President of Albania Albania Juela Hamati President, European Democracy Youth Network Albania Nassera Dutour President, Federation Against Enforced Disappearances (FEMED) Algeria Fatiha Serour United Nations Deputy Special Representative for Somalia; Co-founder, Justice Impact Algeria Rafael Marques de MoraisFounder, Maka Angola Angola Laura Alonso Former Member of Chamber of Deputies; Former Executive Director, Poder Argentina Susana Malcorra Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina; Former Chef de Cabinet to the Argentina Patricia Bullrich Former Minister of Security of Argentina Argentina Mauricio Macri Former President of Argentina Argentina Beatriz Sarlo Journalist Argentina Gerardo Bongiovanni President, Fundacion Libertad Argentina Liliana De Riz Professor, Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo Argentina Flavia Freidenberg Professor, the Institute of Legal Research of the National Autonomous University of Argentina Santiago Cantón Secretary of Human Rights for the Province of Buenos Aires Argentina Haykuhi Harutyunyan Chairperson, Corruption Prevention Commission Armenia Gulnara Shahinian Founder and Chair, Democracy Today Armenia Tom Gerald Daly Director, Democratic Decay & Renewal (DEM-DEC) Australia Michael Danby Former Member of Parliament; Chair, the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee Australia Gareth Evans Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Australia and -

Azerbaijan: the Repression Games

AZERBAIJAN: THE REPRESSION GAMES THE VOICES YOU WON’T HEAR AT THE FIRST EUROPEAN GAMES 1 The first ever European Games are due to take place in (Above) Flame Towers in downtown Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, on 12-28 June 2015. This Baku © Amnesty International multi-sport event will involve around 6,000 athletes and features a new state-of-the-art stadium costing some US$640 million. The games will give a huge boost to the government’s campaign to portray Azerbaijan as a progressive and politically stable rising economic Key Country Facts power. According to the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, the hosting of the European Games ‘will enable Azerbaijan to assert itself again Head of State throughout Europe as a strong, growing and a modern state.’2 President Ilham Aliyev But behind the image trumpeted by the government of a forward-looking, Head of Government modern nation is a state where criticism of the authorities is routinely Artur Rasizadze and increasingly met with repression. Journalists, political activists and human rights defenders who dare to challenge the government face Population trumped up charges, unfair trials and lengthy prison sentences. 9,583,200 In recent years, the Azerbaijani authorities have mounted an Area unprecedented clampdown on independent voices within the country. 86,600 km2 They have done so quietly and incrementally with the result that their actions have largely escaped consequences. The effects, however, are unmistakable. When Amnesty International visited the country in March 2015, there was almost no evidence of independent civil society activities and dissenting voices have been effectively muzzled. -

1 the Responsibility of a Politician: Leyla Yunus and the Heirs Of

The Responsibility of a Politician: Leyla Yunus and the Heirs of Andrei Sakharov Thomas de Waal October 11, 2014 Dear Colleague, In 1989 during some of the most tumultuous days of perestroika, Andrei Sakharov stood up in the Soviet Union's first popularly elected parliament, the Congress of People's Deputies, and called for the end of the monopoly on power of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Sakharov was an influential voice, but also a lonely one, speaking amidst a cacophony of old Communist Party nomenklatura officials on the one hand and aspiring nationalists on the other. At the same time, in the Soviet Union's non-Russian republics, a few brave activists were inspired by the courage of Sakharov and others. They stepped forward and spoke out about the rights of their republics to win independence and achieve democracy. These activists were strongest in the three Baltic republics and the three republics of the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. In Azerbaijan, the struggle was especially difficult. The Communist Party apparatus clung tenaciously to power. The Popular Front of Azerbaijan had a radical nationalist wing that was ready to use violence. All the while the mutually suicidal conflict with Armenia over the disputed region of Nagorny Karabakh was heating up. A small band of academics and intellectuals in the city of Baku were the first to talk about democracy, the first to warn about the dangers of "provocations" and the first to speak up about the defence of the Armenian minority still living in Azerbaijan. They combined courage with intellectual insight about where their republic was heading. -

The Jails of Azerbaijan

The jails of Azerbaijan A chronology of recent repression 14 May to 25 August 2014 ESI Background briefing Introduction Azerbaijan assumed the chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (CoE) on 14 May 2014. Here is what happened since then until 25 August 2014: arrests, pre-trial detainments, court sentences, and other forms of politically motivated repression, the most serious and brutal crackdown on civil society in Azerbaijan ever. May 2014 14 May – in May Azerbaijan took over chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (CoE) from Austria, to lead the Committee for the next six months. 15 May – One day later, the Baku Grave Crimes Court sentenced journalist and human rights activist Parviz Hashimli to eight years in prison on charges of arms possession and smuggling. Hashimli is a reporter for the independent newspaper, Bizim Yol (“Our Way”), and director of the site “Moderator.az.” He had also been arrested eight months earlier 17 September 2013, by officers from the Ministry of National Security. 22 May – The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) issued a decision in the case of Ilgar Mammadov, Chairman of the Republican Alternative Civic Movement (REAL). Mammadov was arrested and detained on 4 February 2013 (along with Tofig Yagublu, a leader in the Musavat oppotition party). The two were charged with organising and initiating a violent mass protest in Ismayilli, Azerbaijan, which occured on 23 January 2014. The ECHR ruled that Mammadov’s three month pre-trial detention was politically motivated and orders the Azerbaijani government to pay him 20,000 EUR. -

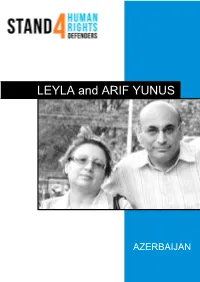

LEYLA and ARIF YUNUS

LEYLA and ARIF YUNUS AZERBAIJAN DESCRIPTION OF THE CASE (2014 - present) Leyla Yunus (59) and her husband Arif Yunus (60) were arrested Leyla Yunus is a long on 30 July 2014. time human rights defender. After spending one year in a pre-trial detention, on 13 August 2015 the Baku Court for Grave Crimes sentenced Leyla and Arif Yunus She is a Director of the to 8.5 and 7 years respectively. Charges brought against Leyla Yunus include state treason (article 274 of the criminal code of Institute for Peace and Azerbaijan), large-scale fraud (article 178.3.2), forgery (article Democracy. 320), tax evasion (article 213), and illegal entrepreneurship (article 192). Arif Yunus is charged with state treason and fraud. A historian by training, she is known The persecution against Leyla and Arif Yunus started in late April for calling for peace during the 2014, when travel bans were imposed on them and their passports Azerbaijan-Armenia hostilities and were confiscated. The period of pre-trial detention of Leyla and Arif lead people-to-people dialogue Yunus was extended twice. The first hearing on the case took place between the two states. on 15 July 2015, almost one year after their detention. Both Leyla and Arif are suffering from life-threatening health During the Eurovision Song Contest, conditions. Leyla Yunus has diabetes and hepatitis C. During the she gave an interview to the court hearing in early August 2015, Arif Yunus suffered a severe Washington Post on the illegal hypertensive crisis. demolition of citizens’ houses in Baku. Subsequently, the building of the International organisations have been calling for the immediate Institute for Peace and Democracy release of the couple and for all charges against them to be was itself illegally demolished. -

The Book of Sakharov Prize Laureates 2016

THE BOOK OF SAKHAROV PRIZE LAUREATES 2016 2016 Nadia Murad Basee Taha, Lamiya Aji Bashar 2002 Oswaldo José Payá Sardiñas 2015 Raif Badawi 2001 Izzat Ghazzawi, Nurit Peled-Elhanan, 2014 Denis Mukwege Dom Zacarias Kamwenho 2013 Malala Yousafzai 2000 ¡Basta Ya! 2012 Nasrin Sotoudeh, Jafar Panahi 1999 Xanana Gusmão 2011 Arab Spring: 1998 Ibrahim Rugova Mohamed Bouazizi, Ali Ferzat, Asmaa Mahfouz, 1997 Salima Ghezali Ahmed El Senussi, Razan Zaitouneh 1996 Wei Jingsheng 2010 Guillermo Fariñas 1995 Leyla Zana 2009 Memorial 1994 Taslima Nasreen 2008 Hu Jia 1993 Oslobođenje 2007 Salih Mahmoud Mohamed Osman 1992 Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo 2006 Aliaksandr Milinkevich 1991 Adem Demaçi 2005 Damas de Blanco, Hauwa Ibrahim, 1990 Aung San Suu Kyi Reporters Without Borders 1989 Alexander Dubček 2004 The Belarusian Association of Journalists 1988 Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, 2003 United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan Anatoli Marchenko and all the staff of the UN FOREWORD Martin Schulz President of the European Parliament As we approach the end of 2016, it is difficult to be optimistic. Bombs are raining down on Syrian cities and their inhabitants day and night, the list of prisoners of conscience around the world is getting longer and longer and populist propaganda attacking democratic values has reached the very heart of the Union. The European Parliament is not standing idly by. In the name of freedom of expression and the right to speak out against suffering and injustice, it is trying to help those whose governments seek to silence them. It does so in any way it can, sometimes in private, and sometimes in public, such as by awarding the annual Sakharov Prize, which casts a spotlight on one particular struggle. -

The Old-New Arenas of Imperialism – Western Asia and North Africa

Kraków 2015 © Copyright by Villa Decius Association 2015 Edited by: Danuta Glondys, Ph.D. Ziemowit Jóźwik Coedited by: Dominika Kasprowicz, Ph.D. Conference concept: Dominika Kasprowicz, Wojciech Przybylski Cooperation: Olga Glondys Translation: Piotr Krasnowolski Proofreading: Martin Cahn Photographs: Tomasz Kizny Paweł Mazur Design and composition: Piotr Hrehorowicz, Małgorzata Punzet, Inter Line SC Printed by: Drukarnia Leyko sp. z o.o. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Villa Decius Association. ISBN 978-83-61600-05-3 Introduction Dominika The first fifteen years of the twenty-first century have opened a new chapter in the world’s history. Kasprowicz | In analysts’ opinion, its current content and following pages will be filled primarily with geopolitical events and technological innovations. The former will mainly include relatively new international conflicts (like in Libya, Syria and Ukraine) and escalation of the ongoing wars in Africa (Somalia, Sudan) and Middle East. The second subsection of the new chapter will deal with socio-political issues, especially growing protests against corporate globalization and their influence on institutions of liberal democracy. The last critical factor that manifests itself in various places of the world is the fundamentalist threat to the West. All three themes, their origins and results are nothing new in a sense that they fit into a global pattern of the rise and fall of societies traceable back to the ancient times. However, the cycle of rise and decline appears to be accelerating under the influence of the digital revolution and technological innovations.