D Harma Connection 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

The Ven. Eido Tai Shimano Roshi, Founder of Two American Rinzai Zen

The Ven. Eido Tai Shimano Roshi, founder of two American Rinzai Zen temples, died February 18 shortly after presenting teachings at Shogen-ji Junior College in Gifu, Japan. He was 85. He moved to Hawaii in 1960 after many years of intensive practice at Ryutaku-ji in Mishima, Japan with the late Soen Nakagawa Roshi. He settled in New York City in 1965, and was asked to become president of the Zen Studies Society, which had been established in 1956 to assist the Buddhist scholar D.T. Suzuki in his pioneering efforts to introduce Zen to the West. He established New York Zendo Shobo-Ji, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, on Sept. 15, 1968, and International Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-Ji, in the Catskill Mountains of Upstate New York, on July 4, 1976. Eido Roshi received Dharma Transmission from Soen Nakagawa Roshi on Sept. 15, 1972, and served as the abbot of New York Zendo and Dai Bosatsu Zendo until his retirement in 2010. He was the author of Points of Departure; Golden Wind; and Zen Word, Zen Calligraphy. He brought out a translation of The Book of Rinzai: the Recorded Sayings of Master Rinzai, and translated several volumes of Eihei Dogen’s Shobogenzo. He gave teachings and held retreats throughout the world, and was the recipient of the Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai award, honoring his remarkable achievements and contributions in bringing the teachings of Buddhism to the West. In the Postscript to his section of the book Namu Dai Bosa: A Transmission of Zen Buddhism to America, edited by Louis Nordstrom, Eido Roshi wrote: “On the Way to Dai Bosatsu I met many travelers. -

SNOW LION PUBLI C'ltl Olss JANET BUDD 946 NOTTINGHAM DR

M 17 BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID ITHACA, NY 14851 Permit No. 746 SNOW LION PUBLI C'lTl OLsS JANET BUDD 946 NOTTINGHAM DR REDLANDS CA SNOW LION ORDER FROM OUR NEW TOLL FREE NUMBER NEWSLETTER & CATALOG 1-800-950-0313 SPRING 1992 SNOW LION PUBLICATIONS PO BOX 6483, ITHACA, NY 14851, (607)-273-8506 ISSN 1059-3691 VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 Nyingma Transmission The Statement of His Holiness How 'The Cyclone' Came to the West the Dalai Lama on the Occasion by Mardie Junkins of the 33rd Anniversary of Once there lived a family in the practice were woven into their he danced on the rocks in an ex- village of Joephu, in the Palrong lives. If one of the children hap- plosion of radiant energy. Not sur- the Tibetan National Uprising valley of the Dhoshul region in pened to wake in the night, the prisingly, Tsa Sum Lingpa is Eastern Tibet. There was a father, father's continuous chanting could especially revered in the Dhoshul mother, two sisters, and two be heard. region of Tibet. As we commemorate today the brothers. Like many Tibetan fam- The valley was a magical place The oldest of the brothers was 33rd anniversary of the March ilies they were very devout. The fa- with a high mountain no one had nicknamed "The Cyclone" for his 10th Uprising in 1959,1 am more ther taught his children and the yet climbed and a high lake with enormous energy. He would run optimistic than ever before about children of the village the Bud- milky white water and yellow crys- up a nearby mountain to explore the future of Tibet. -

Fall 1969 Wind Bell

PUBLICATION OF ZEN •CENTER Volume Vilt Nos. 1-2 Fall 1969 This fellow was a son of Nobusuke Goemon Ichenose of Takahama, the province of Wakasa. His nature was stupid and tough. When he was young, none of his relatives liked him. When he was twelve years old, he was or<Llined as a monk by Ekkei, Abbot of Myo-shin Monastery. Afterwards, he studied literature under Shungai of Kennin Monastery for three years, and gained nothing. Then he went to Mii-dera and studied Tendai philosophy under Tai-ho for. a summer, and gained nothing. After this, he went to Bizen and studied Zen under the old teacher Gisan for one year, and attained nothing. He then went to the East, to Kamakura, and studied under the Zen master Ko-sen in the Engaku Monastery for six years, and added nothing to the aforesaid nothingness. He was in charge of a little temple, Butsu-nichi, one of the temples in Engaku Cathedral, for one year and from there he went to Tokyo to attend Kei-o College for one year and a half, making himself the worst student there; and forgot the nothingness that he had gained. Then he created for himself new delusions, and came to Ceylon in the spring of 1887; and now, under the Ceylon monk, he is studying the Pali Language and Hinayana Buddhism. Such a wandering mendicant! He ought to <repay the twenty years of debts to those who fed him in the name of Buddhism. July 1888, Ceylon. Soyen Shaku c.--....- Ocean Wind Zendo THE KOSEN ANO HARADA LINEAOES IN AMF.RICAN 7.llN A surname in CAI':> andl(:attt a Uhatma heir• .l.incagea not aignilleant to Zen in Amttka arc not gi•cn. -

Buddhism: a Tale of the Dalai Lama a Teacher’S Resource Guide

1 Buddhism: A Tale of the Dalai Lama A Teacher’s Resource Guide Content Area Relevance: World History, World Religions Grade Level: Grades K-5 Duration: 4, 60-minute class periods Content Standards: See Appendix C below Authors: Shruthi Nagarajan, Cassidy Charles, and Arjun Kaul Email: [email protected] Driving Question ● How does learning about different religions help us develop our cultural awareness, and increase our understanding of global complexities? Learning Objectives: - Students will be able to identify and locate Tibet on a map. - Students will be able to identify Buddhism as a religion and list at least two or three teachings of Buddhism. - Students will learn about the Dalai Lama and core aspects of his teachings. - Students will learn about the spread of Buddhism to East Asia and the U.S. Quick Facts: - Buddhism began in India after Prince Siddhartha Gautama freed himself from the cycle of desire and suffering over 2500 years ago - The religion is based on the Buddha’s teachings of the Four Noble Truths and The Eightfold Path which allow us to reach Nirvana and end suffering - The three main tiers of the Eightfold Path are Wisdom, Morality, and Meditation - The three main sects of Buddhism are Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana Buddhism which each spread to different regions of Asia - Tibetan Buddhism follows a mix of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism - The Dalai Lama is essential to Tibetan Buddhism as the head monk of the religion and a crucial part in Tibetan politics 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Background Information………………………..……………………….……3-4 2. Teacher Guidance…………………………………………………………… 5-9 a. -

Sesshin Sutra Book Jikyouji – Cedar Rapids

Sesshin Sutra Book Jikyouji – Cedar Rapids 2 Table of Contents Robe Verse ………………………………………………………………….... 3 Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra ……………………………………. 4 Harmony of Difference and Sameness ………………………………….. 6 Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi ……………………………………. 8 Jijuyu Zammai ………………………………………………………………… 10 Fukanzazengi …………………………………………………………………. 12 Sutra Opening Verse ………………………………………………………… 15 Sutra Closing Verse ………………………………………………………….. 15 Four Vows ……………………………………………………………………… 15 Meal Verses – short ………………………………………………………….. 16 Meal Verses – long (gyohatsu) ……………………………………………. 17 Sutras for Services Morning ― Heart of Great Wisdom Sutra Noon ― Harmony of Difference and Sameness or Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi Supper ― Jijuyu Zammai End of day ― Fukanzazengi October 2020 3 At end of second period, after the zazen bell rings: (Robe Verse) (for putting on rakusu or okesa) 3 times all: How great, the robe of liberation! A formless field of merit, Wrapping ourselves in Buddha’s teaching We free all beings. Put on rakusu or okesa October 2020 4 Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra (Maha Prajna Paramita Hridaya Sutra) Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, When deeply practicing prajna paramita, Clearly saw that all five aggregates are empty And thus relieved all suffering. Shariputra, form does not differ from emptiness, Emptiness does not differ from form. Form itself is emptiness. Emptiness itself form. Sensations, perceptions, formations, and consciousness are also like this. Shariputra, all Dharmas are marked by emptiness; They neither arise nor cease, Are neither defiled nor pure, Neither increase nor decrease. Therefore, given emptiness, there is no form, No sensation, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; No eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; No sight, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no object of mind; No realm of sight, and so forth, down to no realm of mind-consciousness. -

William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu!

Realize a NHK drama centered on William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu! We request for your support and cooperation with our Petition Campaign! Recognized in Japan by the name, Miura Anjin, this English sailor became the diplomatic advisor to Tokugawa Ieyasu, and greatly contributed to the development of Japan with his profound knowledge of navigation and shipbuilding. Four cities connected to Adams: Usuki of Oita prefecture, Ito of Shizuoka prefecture, Yokosuka of Kanagawa prefecture, and Hirado of Nagasaki prefecture, have formed the “ANJIN Project Committee,” and are working together to honor Adams achievements, and also propose a theme based on William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu for Taiga Drama. Taiga Drama is a renowned historical drama series created by NHK, Japan’s sole public broadcasting organization. Themes for this annual drama are selected from Japan’s rich history. To further increase the chances of our Taiga Drama proposal to NHK, we have started a Petition Campaign! To sign the petition, please fill your name and address on the form below: Petition Form I support the creation of a NHK Taiga Drama based around the theme of William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Address Name Prefecture* Municipality* Land number is e.g. Taro Yokosuka Kanagawa Ogawa-cho, Yokosuka not required. e.g. William Adams U.K. Medway 1 2 按針メモリアルパーク 3 4 5 三浦按針上陸記念公園 6 7 三浦按針之墓 8 9 会社名 10 *Those overseas should write your Country in “Prefecture” (e.g. U.K.) and your City in “Municipality” (e.g. Medway). ・Please submit the completed form to the division below (bring the form directly or send it by mail or FAX). -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE Aotearoa New Zealand Centre for Earthquake Resilience Contents ___ Directors’ Report 3 Chair’s Report 4 About Us 5 Our Outcomes 6 Research Research overview 7 Technology platforms 8 Flagship programmes 9 Other projects 10 Scrap tyres find new lives as earthquake protection 11 How effective is insurance for earthquake risk mitigation? 13 Toward functional buildings following major earthquakes 15 Collaboration to Impact Preparing for quakes: Seismic sensors and early warning systems 17 What makes a resilient community? 19 Collaboration a key tool in natural hazard public education 21 Human Capability Development Connections through quakes: International researchers tour New Zealand 23 Research in Te Ao Māori 25 The QuakeCoRE postgraduate experience 27 Recognition highlights 29 Financials, Community and Outputs Financials 33 At a glance 34 Community 35 Publications 41 Directors’ Report 2019 ___ Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE formed in 2016 with a vision of transforming the QuakeCoRE continues to exhibit collaborative leadership domestically and earthquake resilience of communities throughout Aotearoa New Zealand, and in internationally. We highlight the strong alignment achieved with the ‘Resilience to four years, we are already seeing important progress toward this vision through our Nature’s Challenges’ National Science Challenge, progress associated with our on- focus on research excellence, deep national and international collaborations, and going commitment to Mātauranga Māori, partnership research between the public human capability development. and private sectors through community participation in seismic sensor deployment, and also the ‘Learning from Earthquakes’ programme as an example of international In our fourth Annual Report we highlight several world-class research stories, opportunities to study New Zealand as a natural earthquake laboratory. -

Shinge Roshi VISION

FROM: http://www.zenstudies.org/abbot.html 11/20/10 Shinge Roshi: Biography and Vision After receiving a degree in Creative Writing from Vassar College in 1965 and studying painting at the New York Studio School, Roko Sherry Chayat began practice at the Zen Studies Society’s West Side apartment. She spent a year painting in the South of France, returning to find the New York Zendo newly established at 223 East 67th Street. Becoming an integral part of what is often referred to as the Dai Bosatsu Mandala, she was present at New York Zendo Shobo-ji when the decision was made to purchase the property in the Catskills, and served as co-director of the first residential community at Dai Bosatsu Zendo from 1974 to 1976. Moving to Syracuse, she became the spiritual director of the Zen Center of Syracuse Hoen-ji, which had been founded in 1972. In 1991, Shinge Roshi was ordained by Eido Roshi at Dai Bosatsu Zendo. He installed her as abbot of Hoen-ji in 1996, after the zendo moved from her attic to its current home on six acres along Onondaga Creek in Syracuse’s historic Valley district. In 1998, she received inka shomei, Dharma Transmission, from Eido Roshi. In 2008 he performed the shitsugo or “room naming” ceremony at Hoen-ji, recognizing her as a roshi and giving her the name Shinge, meaning “heart-mind flowering.” In addition to her work as a Zen teacher, Shinge Roshi is an award-winning writer. She compiled and edited Eloquent Silence: Nyogen Senzaki’s Gateless Gate and Other Previously Unpublished Teachings and Letters; Endless Vow: The Zen Path of Soen Nakagawa, with Eido Roshi and Kazuaki Tanahashi; and Subtle Sound: The Zen Teachings of Maurine Stuart. -

A Biomolecular Anthropological Investigation of William Adams, The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A biomolecular anthropological investigation of William Adams, the frst SAMURAI from England Fuzuki Mizuno1*, Koji Ishiya2,3, Masami Matsushita4, Takayuki Matsushita4, Katherine Hampson5, Michiko Hayashi1, Fuyuki Tokanai6, Kunihiko Kurosaki1* & Shintaroh Ueda1,5 William Adams (Miura Anjin) was an English navigator who sailed with a Dutch trading feet to the far East and landed in Japan in 1600. He became a vassal under the Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was bestowed with a title, lands and swords, and became the frst SAMURAI from England. "Miura" comes from the name of the territory given to him and "Anjin" means "pilot". He lived out the rest of his life in Japan and died in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1620, where he was reportedly laid to rest. Shortly after his death, graveyards designated for foreigners were destroyed during a period of Christian repression, but Miura Anjin’s bones were supposedly taken, protected, and reburied. Archaeological investigations in 1931 uncovered human skeletal remains and it was proposed that they were those of Miura Anjin. However, this could not be confrmed from the evidence at the time and the remains were reburied. In 2017, excavations found skeletal remains matching the description of those reinterred in 1931. We analyzed these remains from various aspects, including genetic background, dietary habits, and burial style, utilizing modern scientifc techniques to investigate whether they do indeed belong to the frst English SAMURAI. William Adams was born in Gillingham, England in 1564. He worked in a shipyard from the age of 12, and later studied shipbuilding techniques, astronomy and navigation. -

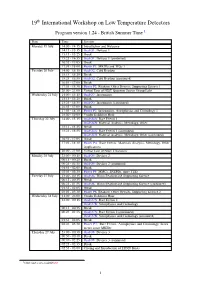

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - British Summer Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 14:00 - 14:15 Introduction and Welcome 14:15 - 15:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O3: Instruments 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 18:00 - 19:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Monday 26 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 01:55 - 02:05 Break 02:05 - 03:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Tuesday 27 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science -

Japanese Gardens at American World’S Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıv | Number ı | Fall 2008 Essays: The Long Life of the Japanese Garden 2 Paula Deitz: Plum Blossoms: The Third Friend of Winter Natsumi Nonaka: The Japanese Garden: The Art of Setting Stones Marc Peter Keane: Listening to Stones Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Tea and Sympathy: A Zen Approach to Landscape Gardening Kendall H. Brown: Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan Book Reviews 18 Joseph Disponzio: The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Garden of Versailles By Ian Thompson Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition By Robert Pogue Harrison Calendar 22 Tour 23 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor times. Still observed is a Marc Peter Keane explains Japanese garden also became of interior and exterior. The deep-seated cultural tradi- how the Sakuteiki’s prescrip- an instrument of propagan- preeminent Wright scholar tion of plum-blossom view- tions regarding the setting of da in the hands of the coun- Anthony Alofsin maintains ing, which takes place at stones, together with the try’s imperial rulers at a in his essay that Wright was his issue of During the Heian period winter’s end. Paula Deitz Zen approach to garden succession of nineteenth- inspired as much by gardens Site/Lines focuses (794–1185), still inspired by writes about this third friend design absorbed during his and twentieth-century as by architecture during his on the aesthetics Chinese models, gardens of winter in her narrative of long residency in Japan, world’s fairs.