One of Mawson's 'Forgotten Men':Robert Bage and His Antarctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S. Antarctic Projects Officer Bullet

S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER BULLET VOLUME III NUMBER 8 APRIL 1962 Instructions given by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty ti James Clark Ross, Esquire, Captain of HMS EREBUS, 14 September 1839, in J. C. Ross, A Voya ge of Dis- covery_and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, . I, pp. xxiv-xxv: In the following summer, your provisions having been completed and your crews refreshed, you will proceed direct to the southward, in order to determine the position of the magnet- ic pole, and oven to attain to it if pssble, which it is hoped will be one of the remarka- ble and creditable results of this expedition. In the execution, however, of this arduous part of the service entrusted to your enter- prise and to your resources, you are to use your best endoavours to withdraw from the high latitudes in time to prevent the ships being besot with the ice Volume III, No. 8 April 1962 CONTENTS South Magnetic Pole 1 University of Miohigan Glaoiologioal Work on the Ross Ice Shelf, 1961-62 9 by Charles W. M. Swithinbank 2 Little America - Byrd Traverse, by Major Wilbur E. Martin, USA 6 Air Development Squadron SIX, Navy Unit Commendation 16 Geological Reoonnaissanoe of the Ellsworth Mountains, by Paul G. Schmidt 17 Hydrographio Offices Shipboard Marine Geophysical Program, by Alan Ballard and James Q. Tierney 21 Sentinel flange Mapped 23 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 24 The Bulletin is pleased to present four firsthand accounts of activities in the Antarctic during the recent season. The Illustration accompanying Major Martins log is an official U.S. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

Leadership Lessons from Sir Douglas Mawson

LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM SIR DOUGLAS MAWSON Sir Douglas Mawson was one of the most courageous and adventurous men Australia has produced. Through his determination and efforts he added to the Commonwealth an area in Antarctica almost as large as Australia itself. He was born in Yorkshire, England May 1882 and at the age of four his parents migrated to Sydney. He was educated at the University of Sydney and played a leading role in founding the Science Society. His great interest was geology and in 1902 he joined expeditions to survey the land around Mittagong and later the New Hebrides Islands. In 1905 he was appointed Lecturer in Mineralogy and Petrology at the University of Adelaide which he served in various capacities until his death. In 1907 a tour of the Snowy Mountains became his first experience of a glacial environment with an ascent of Mount Kosciusko and the beginning of his interest in Antarctica. At this time Britain, Germany and Sweden were involved in Antarctica, Ernest Shackleton was determined to reach the South Pole and in 1907 lead a party with Mawson joining as physicist and surveyor of the expedition. They reached the continent in February 1908 and Shackleton decided that Mawson, Professor Edgeworth David and Dr Forbes MacKay should travel 1800km to the Magnetic Pole. During the expedition they met very bad surfaces and some blizzards and they had underestimated the distance to the Magnetic Pole. While they reached their destination all were in poor condition with only seal meat to eat. They struggled back over hundreds of kilometres of ice caps and at last saw their ship, the Nimrod, less than a kilometre away when suddenly Mawson fell six metres down a crevasse. -

Meet... Douglas Mawson

TEACHERS’ RESOURCES RECOMMENDED FOR Lower and upper primary CONTENTS 1. Plot summary 1 2. About the author 2 3. About the illustrator 2 4. Interview with the author 2 5. Pre-reading questions 2 6. Key study topics 3 7. Other books in this series 4 8. Worksheets 5 KEY CURRICULUM AREAS Learning areas: History, English, Literacy THEMES Australian History Exploration Antarctica PREPARED BY Meet Douglas Mawson Penguin Random House Australia PUBLICATION DETAILS Written by Mike Dumbleton ISBN: 9780857981950 (hardback) Illustrated by Snip Green ISBN: 9780857981974 (ebook) ISBN: 9780857981967 (paperback) These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be PLOT SUMMARY reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. The year 2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the first Australian Antarctic Expedition (1911–14), led Visit penguin.com.au/teachers to find out how our fantastic Penguin Random House Australia books by Douglas Mawson. can be used in the classroom, sign up to the teachers’ newsletter and follow us on In this book, we follow Mawson and his team on @penguinteachers. their journey to Antarctica, as well as on their dangerous and challenging trek across the frozen Copyright © Penguin Random House Australia continent as they attempt to gather scientific and 2014 geological information. Meet Douglas Mawson Mike Dumbleton & Snip Green ABOUT THE AUTHOR 4. What was the most challenging part of the project? Mike Dumbleton is a writer with many educational It was a challenge to tell the story in a way that and children’s books to his credit. -

Cape Denison MAWSON CENTENNIAL 1911–2011, Commonwealth Bay

Cape Denison MAWSON CENTENNIAL 1911–2011, Commonwealth Bay Mawson and the Australasian Geology of Cape Denison Landforms of Cape Denison Position of Cape Denison in Gondwana Antarctic Expedition The two dominant rock-types found at Cape Denison Cape Denison is a small ice-free rocky outcrop covering Around 270 Million years ago the continents that we are orthogneiss and amphibolite. There are also minor less than one square kilometre, which emerges from The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) took place know today were part of a single ancient supercontinent occurrences of coarse grained felsic pegmatites. beneath the continental ice sheet. Stillwell (1918) reported between 1911 and 1914, and was organised and led by called Pangea. Later, Pangea split into two smaller that the continental ice sheet rises steeply behind Cape the geologist, Dr Douglas Mawson. The expedition was The Cape Denison Orthogneiss was described by Stillwell (1918) as supercontinents, Laurasia and Gondwana, and Denison reaching an altitude of ‘1000 ft in three miles and jointly funded by the Australian and British Governments coarse-grained grey quartz-feldspar layered granitic gneiss. These rock Antarctica formed part of Gondwana. with contributions received from various individuals and types are normally formed by metamorphism (changed by extreme heat 1500 ft in five and a half miles’ (approximately 300 metres and pressure) of granites. The Cape Denison Orthogneiss is found around In current reconstructions of the supercontinent Gondwana, the Cape scientific societies, including the Australasian Association to 450 metres over 8.9 kilometres). Photography by Chris Carson Cape Denison, the nearby offshore Mackellar Islands, and nearby outcrops Denison–Commonwealth Bay region was located adjacent to the coast for the Advancement of Science. -

The Harrowing Story of Shackletons Ross Sea Party Pdf Free Download

THE LOST MEN: THE HARROWING STORY OF SHACKLETONS ROSS SEA PARTY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kelly Tyler-Lewis | 384 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780747579724 | English | London, United Kingdom Ross Sea party - Wikipedia Aurora finally broke free from the ice on 12 February and managed to reach New Zealand on 2 April. Because Mackintosh had intended to use Aurora as the party's main living quarters, most of the shore party's personal gear, food, equipment and fuel was still aboard when the ship departed. Although the sledging rations intended for Shackleton's depots had been landed, [41] the ten stranded men were left with "only the clothes on their backs". We cannot expect rescue before then, and so we must conserve and economize on what we have, and we must seek and apply what substitutes we can gather". On the last day of August Mackintosh recorded in his diary the work that had been completed during the winter, and ended: "Tomorrow we start for Hut Point". The second season's work was planned in three stages. Nine men in teams of three would undertake the sledging work. The first stage, hauling over the sea ice to Hut Point, started on 1 September , and was completed without mishap by the end of the month. Shortly after the main march to Mount Hope began, on 1 January , the failure of a Primus stove led to three men Cope, Jack and Gaze returning to Cape Evans, [49] where they joined Stevens. The scientist had remained at the base to take weather measurements and watch for the ship. -

Australian Antarctic Magazine

AusTRALIAN MAGAZINE ISSUE 23 2012 7317 AusTRALIAN ANTARCTIC ISSUE 2012 MAGAZINE 23 The Australian Antarctic Division, a Division of the Department for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, leads Australia’s CONTENTS Antarctic program and seeks to advance Australia’s Antarctic interests in pursuit of its vision of having PROFILE ‘Antarctica valued, protected and understood’. It does Charting the seas of science 1 this by managing Australian government activity in Antarctica, providing transport and logistic support to SEA ICE VOYAGE Australia’s Antarctic research program, maintaining four Antarctic science in the spring sea ice zone 4 permanent Australian research stations, and conducting scientific research programs both on land and in the Sea ice sky-lab 5 Southern Ocean. Search for sea ice algae reveals hidden Antarctic icescape 6 Australia’s four Antarctic goals are: Twenty metres under the sea ice 8 • To maintain the Antarctic Treaty System and enhance Australia’s influence in it; Pumping krill into research 9 • To protect the Antarctic environment; Rhythm of Antarctic life 10 • To understand the role of Antarctica in the global SCIENCE climate system; and A brave new world as Macquarie Island moves towards recovery 12 • To undertake scientific work of practical, economic and national significance. Listening to the blues 14 Australian Antarctic Magazine seeks to inform the Bugs, soils and rocks in the Prince Charles Mountains 16 Australian and international Antarctic community Antarctic bottom water disappearing 18 about the activities of the Australian Antarctic Antarctic bioregions enhance conservation planning 19 program. Opinions expressed in Australian Antarctic Magazine do not necessarily represent the position of Antarctic ice clouds 20 the Australian Government. -

Antarctica: at the Heart of It All

4/8/2021 Antarctica: At the heart of it all Dr. Dan Morgan Associate Dean – College of Arts & Science Principal Senior Lecturer – Earth & Environmental Sciences Vanderbilt University Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Spring 2021 Webcams for Antarctic Stations III: “Golden Age” of Antarctic Exploration • State of the world • 1910s • 1900s • Shackleton (Nimrod) • Drygalski • Scott (Terra Nova) • Nordenskjold • Amundsen (Fram) • Bruce • Mawson • Charcot • Shackleton (Endurance) • Scott (Discovery) • Shackleton (Quest) 1 4/8/2021 Scurvy • Vitamin C deficiency • Ascorbic Acid • Makes collagen in body • Limits ability to absorb iron in blood • Low hemoglobin • Oxygen deficiency • Some animals can make own ascorbic acid, not higher primates International scientific efforts • International Polar Years • 1882-83 • 1932-33 • 1955-57 • 2007-09 2 4/8/2021 Erich von Drygalski (1865 – 1949) • Geographer and geophysicist • Led expeditions to Greenland 1891 and 1893 German National Antarctic Expedition (1901-04) • Gauss • Explore east Antarctica • Trapped in ice March 1902 – February 1903 • Hydrogen balloon flight • First evidence of larger glaciers • First ice dives to fix boat 3 4/8/2021 Dr. Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjold (1869 – 1928) • Geologist, geographer, professor • Patagonia, Alaska expeditions • Antarctic boat Swedish Antarctic Expedition: 1901-04 • Nordenskjold and 5 others to winter on Snow Hill Island, 1902 • Weather and magnetic observations • Antarctic goes north, maps, to return in summer (Dec. 1902 – Feb. 1903) 4 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 1 • November and December, 1902 too much ice • December 1902: Three meant put ashore at hope bay, try to sledge across ice • Can’t make it, spend winter in rock hut 5 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 2 • Antarctic stuck in ice, January 1903 • Crushed and sinks, Feb. -

Flnitflrcililcl

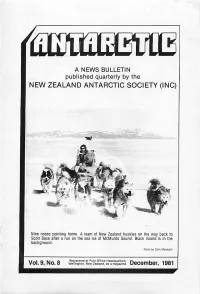

flNiTflRCililCl A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) svs-r^s* ■jffim Nine noses pointing home. A team of New Zealand huskies on the way back to Scott Base after a run on the sea ice of McMurdo Sound. Black Island is in the background. Pholo by Colin Monteath \f**lVOL Oy, KUNO. O OHegisierea Wellington, atNew kosi Zealand, uttice asHeadquarters, a magazine. n-.._.u—December, -*r\n*1981 SOUTH GEORGIA SOUTH SANDWICH Is- / SOUTH ORKNEY Is £ \ ^c-c--- /o Orcadas arg \ XJ FALKLAND Is /«Signy I.uk > SOUTH AMERICA / /A #Borga ) S y o w a j a p a n \ £\ ^> Molodezhnaya 4 S O U T H Q . f t / ' W E D D E L L \ f * * / ts\ xr\ussR & SHETLAND>.Ra / / lj/ n,. a nn\J c y DDRONNING d y ^ j MAUD LAND E N D E R B Y \ ) y ^ / Is J C^x. ' S/ E A /CCA« « • * C",.,/? O AT S LrriATCN d I / LAND TV^ ANTARCTIC \V DrushsnRY,a«feneral Be|!rano ARG y\\ Mawson MAC ROBERTSON LAND\ \ aust /PENINSULA'5^ *^Rcjnne J <S\ (see map below) VliAr^PSobral arg \ ^ \ V D a v i s a u s t . 3_ Siple _ South Pole • | U SA l V M I IAmundsen-Scott I U I I U i L ' l I QUEEN MARY LAND ^Mir"Y {ViELLSWORTHTTH \ -^ USA / j ,pt USSR. ND \ *, \ Vfrs'L LAND *; / °VoStOk USSR./ ft' /"^/ A\ /■■"j■ - D:':-V ^%. J ^ , MARIE BYRD\Jx^:/ce She/f-V^ WILKES LAND ,-TERRE , LAND \y ADELIE ,'J GEORGE VLrJ --Dumont d'Urville france Leningradskaya USSR ,- 'BALLENY Is ANTARCTIC PENIMSULA 1 Teniente Matienzo arg 2 Esperanza arg 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Deception arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Arturo Prat chile 8 Bernardo O'Higgins chile 9 P r e s i d e n t e F r e i c h i l e : O 5 0 0 1 0 0 0 K i l o m e t r e s 10 Stonington I. -

Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan Prime Minister’S Foreword

Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan Prime Minister’s Foreword Australia has inherited a proud legacy from Sir Douglas Significant progress has already been made by the Mawson and the generations of Australian Antarctic Government on improving aviation access to Antarctica. expeditioners who have followed in his footsteps - a We have undertaken C-17A trial flights to provide an option legacy of heroism, scientific endeavour and environmental for a new heavy-lift cargo capability. Work will continue stewardship. across Government to further build support for the Australian Antarctic programme. Mawson’s legacy has forged, for all Australians, a profound and significant connection with Antarctica. The Australian The Government’s investment in Antarctic capability, in Antarctic Territory occupies a unique place in our national support of Antarctic science, represents a step change in identity. our Antarctic programme and will equip us to be a partner of choice in East Antarctica and to work even more closely Australia’s Antarctic science programme is one of our most with other countries within the Antarctic Treaty system. iconic and enduring national endeavours. Antarctica is of great importance to Australians, and Antarctic science will A strong and effective Antarctic Treaty system is in continue to be one of our national priorities. Australia’s national interest. The Government will use our international engagement to build and maintain strong and Antarctica is an extreme and hostile environment. Modern effective relationships with other nations in support of the and effective Antarctic operations and logistics capabilities Antarctic Treaty system. -

SECTION THREE: Historic Sites and Monuments in Antarctica

SECTION THREE: Historic Sites and Monuments in Antarctica The need to protect historic sites and monuments became apparent as the number of expeditions to the Antarctic increased. At the Seventh Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting it was agreed that a list of historic sites and monuments be created. So far 74 sites have been identified. All of them are monuments – human artifacts rather than areas – and many of them are in close proximity to scientific stations. Provision for protection of these sites is contained in Annex V, Article 8. Listed Historic Sites and Monuments may not be damaged, removed, or destroyed. 315 List of Historic Sites and Monuments Identified and Described by the Proposing Government or Governments 1. Flag mast erected in December 1965 at the South Geographical Pole by the First Argentine Overland Polar Expedition. 2. Rock cairn and plaques at Syowa Station (Lat 69°00’S, Long 39°35’E) in memory of Shin Fukushima, a member of the 4th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition, who died in October 1960 while performing official duties. The cairn was erected on 11 January 1961, by his colleagues. Some of his ashes repose in the cairn. 3. Rock cairn and plaque on Proclamation Island, Enderby Land, erected in January 1930 by Sir Douglas Mawson (Lat 65°51’S, Long 53°41’E) The cairn and plaque commemorate the landing on Proclamation Island of Sir Douglas Mawson with a party from the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition of 1929 31. 4. Station building to which a bust of V. I. Lenin is fixed, together with a plaque in memory of the conquest of the Pole of Inaccessibility by Soviet Antarctic explorers in 1958 (Lat 83°06’S, Long 54°58’E). -

Explore Tasmania's Antarctic Heritage

COVER IMAGE: STEPHEN WALKER’S SCULPTURE OF LOUIS BERNACCHI, TASMANIAN ANTARCTIC PIONEER Explore Tasmania’s Antarctic heritage 20 Wireless Institute Tasmania’s connection with Antarctica goes back millions of years, At the top of Hobart’s Queen’s Domain is a weatherboard house with a direct historical link to Australia’s own to when continents were fused in the supercontinent of Gondwana. Douglas Mawson – and pride of place in the history of Antarctic communications. Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic When Gondwana broke up, Tasmania was last to separate. Expedition (1911-1914) was first to use the new wireless technology to communicate between Antarctica and We also share a long human history, starting with James Cook’s epic the outside world. Australia’s new national government built a radio station and a mast over 50 metres high on the Domain which received signals from Mawson via Macquarie Island. From 1922 the station became a part of a Antarctic voyage of the 1770s. Hobart, a major base for 19th century Antarctic nationwide network used for maritime safety – a vital link for Southern Ocean sailors. sealing and whaling, featured in the historic voyages of James Clark Ross, 21 Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens Dumont d’Urville, Carsten Borchgrevink, Douglas Mawson and Roald Amundsen. The Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens, established in 1818 – the second oldest in Australia – feature a unique Today, as headquarters for Australian Antarctic operations, host city for Subantarctic Plant House in a refrigerated building where plants subantarctic island plants are displayed in a international Antarctic organisations and a major centre for Antarctic research, controlled wet and chilly environment.