Death in the Life and Work of Damien Hirst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

PRESS RELEASE Los Angeles Collectors Jane and Marc

PRESS RELEASE Los Angeles Collectors Jane and Marc Nathanson Give Major Artworks to LACMA Art Will Be Shown with Other Promised Gifts at 50th Anniversary Exhibition in April (Image captions on page 3) (Los Angeles, January 26, 2015)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is pleased to announce eight promised gifts of art from Jane and Marc Nathanson. The Nathansons’ gift of eight works of contemporary art includes seminal pieces by Damien Hirst, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and others. The bequest is made in honor of LACMA’s 50th anniversary in 2015. The gifts kick off a campaign, chaired by LACMA trustees Jane Nathanson and Lynda Resnick, to encourage additional promised gifts of art for the museum’s anniversary. Gifts resulting from this campaign will be exhibited at LACMA April 26–September 7, 2015, in an exhibition, 50 for 50: Gifts on the Occasion of LACMA’s Anniversary. "What do you give a museum for its birthday? Art. As we reach the milestone of our 50th anniversary, it is truly inspiring to see generous patrons thinking about the future generations of visitors who will enjoy these great works of art for years and decades to come,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “Jane and Marc Nathanson have kicked off our anniversary year in grand fashion.” Jane Nathanson added, “I hope these gifts will inspire others to make significant contributions in the form of artwork as we look forward not only to the 50th anniversary of the museum, but to the next 50 years. -

Art, Real Places, Better Than Real Places 1 Mark Pimlott

Art, real places, better than real places 1 Mark Pimlott 02 05 2013 Bluecoat Liverpool I/ Many years ago, toward the end of the 1980s, the architect Tony Fretton and I went on lots of walks, looking at ordinary buildings and interiors in London. When I say ordinary, they had appearances that could be described as fusing expediency, minimal composition and unconscious newness. The ‘unconscious’ modern architecture of the 1960s in the city were particularly interesting, as were places that were similarly, ‘unconsciously’ beautiful. We were the ones that were conscious of their raw, expressive beauty, and the basis of this beauty lay in the work of minimal and conceptual artists of that precious period between 1965 and 1975, particularly American artists, such as Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Dan Flavin and Dan Graham. It was Tony who introduced (or re-introduced) me to these artists: I had a strong memory of Minimal Art from visits to the National Gallery in Ottawa, and works of Donald Judd, Claes Oldenburg and Richard Artschwager as a child. There was an aspect of directness, physicality, artistry and individualized or collective consciousness about this work that made it very exciting to us. This is the kind of architecture we wanted to make; and in my case, this is how I wanted to see, make pictures and make environments. To these ends, we made trips to see a lot of art, and art spaces, and the contemporary art spaces in Germany and Switzerland in particular held a special significance for us. I have to say that very few architects in Britain were doing this at the time, or looking at things the way we looked at them. -

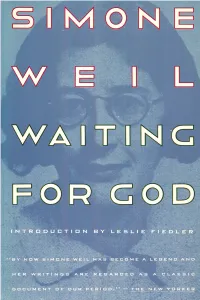

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Press Release

Press Release Abigail Lane Tomorrows World, Yesterdays Fever (Mental Guests Incorporated) Victoria Miro Gallery, 4 October – 10 November 2001 The exhibition is organized by the Milton Keynes Gallery in collaboration with Film and Video Umbrella The Victoria Miro Gallery presents a major solo exhibition of work by Abigail Lane. Tomorrows World, Yesterdays Fever (Mental Guests Incorporated) extends her preoccupation with the fantastical, the Gothic and the uncanny through a trio of arresting and theatrical installations which are based around film projections. Abigail Lane is well known for her large-scale inkpads, wallpaper made with body prints, wax casts of body fragments and ambiguous installations. In these earlier works Lane emphasized the physical marking of the body, often referred to as traces or evidence. In this exhibition Lane turns inward giving form to the illusive and intangible world of the psyche. Coupled with her long-standing fascination with turn-of-the-century phenomena such as séances, freak shows, circus and magic acts, Lane creates a “funhouse-mirror reflection” of the life of the mind. The Figment explores the existence of instinctual urges that lie deep within us. Bathed in a vivid red light, the impish boy-figment beckons us, “Hey, do you hear me…I’m inside you, I’m yours…..I’m here, always here in the dark, I am the dark, your dark… and I want to play….”. A mischievous but not sinister “devil on your shoulder” who taunts and tempts us to join him in his wicked game. The female protagonist of The Inclination is almost the boy-figment’s antithesis. -

Anya Gallaccio

Anya Gallaccio 1963 Born in Paisley, Scotland Lives and works in London, UK Education 1985-1988 Goldsmiths’ College, University of London, UK 1984-1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, UK Residencies and awards 2004 Headlands Center for the Arts, Sansalitos, California, US 2003 Nominee for the Turner Prize, Tate Britain, London, UK 2002 1871 Fellowship, Rothermere American Institute, Oxford, UK San Francisco Art Institute, California, US 1999 Paul Hamlyn Award for Visual Artists, Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award, London, UK 1999 Kanazawa College of Art, JP 1998 Sargeant Fellowship, The British School at Rome, IT 1997 Jan-March Art Pace, International Artist-In-Residence Programme, Foundation for Contemporary Art, San Antonio Texas, US Solo Exhibitions 2015 Lehmann Maupin, New York, US 2014 Stroke, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, UK SNAP, Art at the Aldeburgh Festival, Suffolk, UK Blum&Poe, Los Angeles, US 2013 This much is true, Artpace, San Antonio, Texas, US Creation/destruction, The Holden Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Red on Green, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, UK 2011 Highway, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL Where is Where it’s at, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland including the Dick Institiute, the Baird Institute and the Doon Valley Museum, Kilmarnock, UK 2009 Inaugural Exhibition, Blum & Poe Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, US Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, US 2008 Comfort and Conversation, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL That Open Space Within, Camden Arts Center, London, UK Kinsale -

Londra Al Centro Dell Scena Artistica: La Yung British Art Dalla Conferenza Del 12-05-2011 Del Prof

Londra al centro dell scena artistica: La Yung British Art Dalla conferenza del 12-05-2011 del prof. Francesco Poli a cura del prof. Mario Diegol i Sensation e la YBA (Young British Artists) Il 28 dicembre del 1997 presso la Royal Academy of Art di Londra il collezionista d’arte contemporanea Charles Saatchi organizza la mostra Sensation in cui espone le opere della Yung British Art. La mostra è, in seguito, riproposta a Berl ino e New York e diventa, grazie all’abilità manageriale di Saatchi e alla sua rete di contatt i sviluppata negl i anni precedenti con la sua att ività di pubbl icitario, l’evento artistico del momento e un riferimento importante per il mercato dell’arte portando alla ribalta una serie di giovani art isti inglesi come: Jake & Dinos Chapman, Adam Chodzko, Mat Coll ishaw, Tracey Emin, Marcus Harvey, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Abigail Lane, Sarah Lucas, Chris Ofil i, Richard Patterson, Simon Patterson, Marc Quinn, Fiona Rae, Sam Taylor-Wood, Gavin Turk, Gill ian Wearing, Rachel Whiteread. Gl i artist i della Yung British Art propongono opere che sol itamente tendono a stupire e a provocare lo spettatore. Sono giovani nati negl i anni sessanta che impiegano linguaggi differenti non sempre omologabil i alle tradizional i espressioni plastiche e visive anche se ne recuperano a volte i material i (la pittura, la scultura in marmo) mischiandoli o alternandol i all’impiego di oggetti, fotograf ie, material i plastici, stoffe ecc.. Il manifesto della mostra Sensation con cui evocano e amplificano storie personal i e collettive dove il soggetto e il contenuto prevalgono sulla forma: una forma a volte iperreal istica, in altri casi mostruosa e raccapricciante ampl ificata da dimensioni che possono assumere una scala monumentale. -

Shock Value: the COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR?

Shock Value: THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? BY REENA JANA SHOCK VALUE: enough to prompt San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker to state, “I THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? don’t know another private collection as heavy on ‘shock art’ as Logan’s is.” When asked why his tastes veer toward the blatantly gory or overtly sexual, Logan doesn’t attempt to deny that he’s interested in shock art. But he does use predictably general terms to “defend” his collection, as if aware that such a collecting strategy may need a defense. “I have always sought out art that faces contemporary issues,” he says. “The nature of contemporary art is that it isn’t necessarily pretty.” In other words, collecting habits like Logan’s reflect the old idea of le bourgeoisie needing a little épatement. Logan likes to draw a line between his tastes and what he believes are those of the status quo. “The majority of people in general like to see pretty things when they think of what art should be. But I believe there is a better dialogue when work is unpretty,” he says. “To my mind, art doesn’t fulfill its function unless there’s ent Logan is burly, clean-cut a dialogue started.” 82 and grey-haired—the farthestK thing you could imagine from a gold-chain- Indeed, if shock art can be defined, it’s art that produces a visceral, 83 wearing sleazeball or a death-obsessed goth. In fact, the 57-year-old usually often unpleasant, reaction, a reaction that prompts people to talk, even if at sports a preppy coat and tie. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Resource What Is Modern and Contemporary Art

WHAT IS– – Modern and Contemporary Art ––– – –––– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ––– – – – – ? www.imma.ie T. 00 353 1 612 9900 F. 00 353 1 612 9999 E. [email protected] Royal Hospital, Military Rd, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 Ireland Education and Community Programmes, Irish Museum of Modern Art, IMMA THE WHAT IS– – IMMA Talks Series – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ? There is a growing interest in Contemporary Art, yet the ideas and theo- retical frameworks which inform its practice can be complex and difficult to access. By focusing on a number of key headings, such as Conceptual Art, Installation Art and Performance Art, this series of talks is intended to provide a broad overview of some of the central themes and directions in Modern and Contemporary Art. This series represents a response to a number of challenges. Firstly, the 03 inherent problems and contradictions that arise when attempting to outline or summarise the wide-ranging, constantly changing and contested spheres of both art theory and practice, and secondly, the use of summary terms to describe a range of practices, many of which emerged in opposition to such totalising tendencies. CONTENTS Taking these challenges into account, this talks series offers a range of perspectives, drawing on expertise and experience from lecturers, artists, curators and critical writers and is neither definitive nor exhaustive. The inten- What is __? talks series page 03 tion is to provide background and contextual information about the art and Introduction: Modern and Contemporary Art page 04 artists featured in IMMA’s exhibitions and collection in particular, and about How soon was now? What is Modern and Contemporary Art? Contemporary Art in general, to promote information sharing, and to encourage -Francis Halsall & Declan Long page 08 critical thinking, debate and discussion about art and artists. -

Download Press Release Here

! For Immediate Release 1 May 2019 Artists Announced for New Contemporaries 70th Anniversary Constantly evolving and developing along with the changing face of visual art in the UK, to mark its 70th anniversary, New Contemporaries is pleased to announce this year's selected artists with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. The panel of guest selectors comprising Rana Begum, Sonia Boyce and Ben Rivers has chosen 45 artists for the annual open submission exhibition. Since 1949 New Contemporaries has played a vital part in the story of contemporary British art. Throughout the exhibition's history, a wealth of established artists have participated in New Contemporaries exhibitions including post-war figures Frank Auerbach and Paula Rego; pop artists Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney; YBAs Damien Hirst and Gillian Wearing; alongside contemporary figures such as Tacita Dean, Mark Lecky, Mona Hatoum, Mike Nelson and Chris Ofili; whilst more recently a new generation of artists including Ed Atkins, Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Rachel Maclean and Laure Prouvost have also taken part. Selected artists for Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2019 are: Jan Agha, Eleonora Agostini, Justin Apperley, Ismay Bright, Roland Carline, Liam Ashley Clark, Becca May Collins, Rafael Pérez Evans, Katharina Fitz, Samuel Fordham, Chris Gilvan- Cartwright, Gabriela Giroletti, Roei Greenberg, Elena Helfrecht, Mary Herbert, Laura Hindmarsh, Cyrus Hung, Yulia Iosilzon, Umi Ishihara, Alexei Alexander Izmaylov, Paul Jex, Eliot Lord, Annie Mackinnon, Renie Masters, Simone Mudde, Isobel Napier, Louis Blue Newby, Louiza Ntourou, Ryan Orme, Marijn Ottenhof, Jonas Pequeno, Emma Prempeh, Zoe Radford, Taylor Jack Smith, George Stamenov, Emily Stollery, Wilma Stone, Jack Sutherland, Xiuching Tsay, Alaena Turner, Klara Vith, Ben Walker, Ben Yau, Camille Yvert and Stefania Zocco. -

Fundraiser Catalogue As a Pdf Click Here

RE- Auction Catalogue Published by the Contemporary Art Society Tuesday 11 March 2014 Tobacco Dock, 50 Porters Walk Pennington Street E1W 2SF Previewed on 5 March 2014 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London The Contemporary Art Society is a national charity that encourages an appreciation and understanding of contemporary art in the UK. With the help of our members and supporters we raise funds to purchase works by new artists Contents which we give to museums and public galleries where they are enjoyed by a national audience; we broker significant and rare works of art by Committee List important artists of the twentieth century for Welcome public collections through our networks of Director’s Introduction patrons and private collectors; we establish relationships to commission artworks and promote contemporary art in public spaces; and we devise programmes of displays, artist Live Auction Lots Silent Auction Lots talks and educational events. Since 1910 we have donated over 8,000 works to museums and public Caroline Achaintre Laure Prouvost – Special Edition galleries – from Bacon, Freud, Hepworth and Alice Channer David Austen Moore in their day through to the influential Roger Hiorns Charles Avery artists of our own times – championing new talent, supporting curators, and encouraging Michael Landy Becky Beasley philanthropy and collecting in the UK. Daniel Silver Marcus Coates Caragh Thuring Claudia Comte All funds raised will benefit the charitable Catherine Yass Angela de la Cruz mission of the Contemporary Art Society to