A Profile of Buganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report of the Colonies. Uganda 1920

This document was created by the Digital Content Creation Unit University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2010 COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL. No. 1112. UGANDA. REPORT FOR 1920 (APRIL TO DECEMBER). (For Report for 1919-1920 see No. 1079.) LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any T3ookscller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: IMPERIAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONC-ON, W.C.2, and 28, ABINGDON STREET, LONDON, S.W.I; 37, PETER STREET, MANCHESTER; 1, ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF; 23, FORTH STREET, EDINBURGH; or from EASON & SON. LTD., 40-41, LOWER SACKVII.I-E STREET, DUBLIN. 1922. Price 9d. Net. INDEX. PREFACE I. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS II. GOVERNMENT FINANCE III. TRADE, AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRIES IV. LEGISLATION V. EDUCATION VI. CLIMATE AND METEOROLOGY VII. COMMUNICATIONS.. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS' RECEIVED &0dUM£NT$ DIVISION -fTf-ViM-(Hff,>itmrtn«l,.ni ii ii in. No. 1112. Annual Report ON THE Uganda Protectorate FOR THE PERIOD 1st April to 31st December 1920.* PREFACE. 1. Geographical Description.—The territories comprising the Uganda Protectorate lie between Belgian Congo, the Anglo- Egyptian Sudan, Kenya, and the country known until recently as German East Africa (now Tanganyika Territory). The Protectorate extends from one degree of south latitude to the northern limits of the navigable waters of the Victoria Nile at Nimule. It is flanked on the east by the natural boundaries of Lake Rudolf, the river Turkwel, Mount Elgon (14,200 ft.), and the Sio river, running into the north-eastern waters of Lake Victoria, whilst the outstanding features on the western side are the Nile Watershed, Lake Albert, the river Semliki, the Ruwenzori Range (16,794 ft.), and Lake Edward. -

———— “Mudo”: the Soga 'Little Red Riding Hood'

LILLIAN BUKAAYI TIBASIIMA ———— º “Mudo”: The Soga ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ABSTRACT This essay analyses the social underpinnings of the oral tale of “Mudo,” which belongs to the Aarne–Thompson tale type 333, along with a group of similar tales that resemble the action and movement of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Basic to the exposition is Adolf Bastian’s assertion of the fundamental similarity of ideas between all social groups. In the “Mudo” story and its Ugandan variants, the victim is a solitary little girl and the villain a male ogre who devises ways of eating her; the ogre is mostly successful, although in some variants the girl manages to escape. Although these tales come from a great range of cultures and different geographical locations, and the counterpart of the ogre in the European tales is a wolf in disguise, they share elements of plot, characteriza- tion, and motif, and address similar concerns. Introduction USOGA IS PART OF EAS TERN UGANDA, surrounded by water. The B Rev. Fredrick Kisuule Kaliisa1 notes: To the west is river Kiira (Nile) marking the boundary between Buganda and Busoga. To the East is river Mpologoma separating Busoga from Bukedi. To the North are river Mpologoma and Lake Kyoga, forming the boundary be- tween Busoga and Lango. To the south, is Lake Victoria (Nalubaale). It might be the result of the geographical location of Busoga that ogre stories were composed to warn the people against impending harm if they went out alone and stayed in secluded places. Nnalongo Lukude emphasizes this: Historically, Busoga was surrounded by bodies of water and forests, it was very bushy and as a result harboured many wild animals, some of which were man-eaters. -

Table of Contents List of Tables

TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 PROJECT IMPACTS ................................................................................................................ 138 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 138 Summary of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 138 Impacts on Land ....................................................................................................................... 143 6.3.1 Land Requirements and Land Use Context ......................................................................... 143 Impacts on houses – Physical Displacement ........................................................................... 149 Impacts on other structures ...................................................................................................... 153 Impacts on Communal Buildings .............................................................................................. 159 Graves and Cultural Heritage Assets ....................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Crops and Economic Trees .................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Livelihood Activities – Economic Displacement ..................................................... 166 Impacts on Public Utilities/Infrastructure .................................................................................. -

Characterisation of the Livestock Production System and Potential for Enhancing Productivity Through Improved Feeding in Kiboga

Characterisation of the livestock production system and potential for enhancing productivity through improved feeding in Kiboga West DFBA, Kyankwanzi district, Uganda By: Jane Kugonza, Ronald Wabwire, Pius Lutakome, Ben Lukuyu and Josephine Kirui East African Dairy Development Project (EADD) The Feed Assessment Tool (FEAST) is a systematic method to assess local feed resource availability and use. It helps in the design of intervention strategies aiming to optimize feed utilization and animal production. More information and the manual can be obtained at www.ilri.org/feast FEAST is a tool in constant development and improvement. Feedback is welcome and should be directed [email protected]. The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) is not responsible for the quality and validity of results obtained using the FEAST methodology. The Feed Assessment Tool (FEAST) was used to characterize the livestock production system and in particular feed‐related aspects in Kiboga West dairy farmers association (DFBA) of Kyankwanzi, Kyankwanzi district, Uganda. The assessment was carried out through structured group discussions and completion of short questionnaires by key farmers’ representatives1. The following are the findings of the assessment and conclusions for further action. Farming system Kyankwanzi was formerly in Kiboga district but obtained district status in 2004 and is located in the extreme part of Buganda region. The travel distance by road is approximately 220 kilometres from the capital city of Uganda, Kampala. Households in this area are composed of approximately 14 (range 6-20) members and utilise on average 15 acres of pastoral land. Table 1 shows farmers perceptions about average land sizes for different categories of farmers. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be. -

Buganda Relations in 19Th and 20Th Centuries

Bunyoro-Kitara/ Buganda relations in 19th and 20th Centuries. By Henry Ford Miirima Veteran journalist Press Secretary of the Omukama of Bunyoro-Kitara The source of sour relations. In order to understand the relations between Bunyoro-Kitara and Buganda kingdoms in the 19th and 20th centuries, one must first know the origins of the sour relations. The birth of Buganda, after seceeding from Bunyoro-Kitara was the source of hostile relations. This article will show how this sad situation was arrived at. Up to about 1500 Kitara kingdom (today's Bunyoro-Kitara) under Abatembuzi and Abacwezi dynasities was peaceful, intact, with no rebellious princes. When the Abacwezi kings disappeared they left a three-year vacuum on the throne which was filled when four Ababiito princes were traced, and collected from their Luo mother in northern Uganda. They ascended the Kitara throne with their elder, twin brother, Isingoma Mpuuga Rukidi becoming the first Mubiito king. The Babiito dynasity continues today (January 2005) to reign in Bunyoro-Kitara, Buganda, Busoga, Tooro, Kooki, and Ankole. The Abacwezi kings left: behind a structure of local administration based on counties. Muhwahwa(lightweight)county, todays Buganda, was just one of Kitara's counties. In the pages ahead we are going to see that the counties admninistrative strucuture is also the cause of bad relations between. Bunyoro and Buganda. Muhwahwa's small size, hence the need to expand it, as we are about to see in the pages ahead, had a lasting bearing on the relations not only between Bunyoro-Kitara and Buganda, but also between Buganda and the rest of today's Uganda During Abacwezi reign Muhwahwa county under chief Sebwana, was very obedient, and extremely loyal to Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom. -

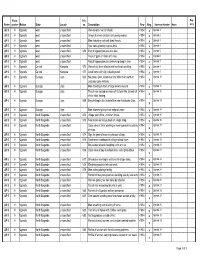

State Locale Description Year Neg. AF 5 H Uganda West Unspecified View

Photo- Print Neg. Binder grapher Nation State Locale no. Description Year Neg. Sorenson Number Notes only AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified View across river to hillside. >1954 x Uganda 1 AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified Group of seven children and young women. >1954 x Uganda 2 AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified Man thatching roof with dried fronds. >1954 x Uganda 3 AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified Four cows grazing in grass field. >1954 x Uganda 4 AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified 686 Pod of hippopotamuses in a lake. >1954 x Uganda 5 AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified Flock of gulls on shore of a lake. >1954 x Uganda 6 AF 5 H Uganda west unspecified Pod of hippopotamuses swimming deep in lake. >1954 x Uganda 7 AF 5 H Uganda Central Kampala 670 View of city from hillside with two locals strolling. >1954 x Uganda 8 AF 5 H Uganda Central Kampala 671 Local home with city in background. >1954 x Uganda 9 AF 5 H Uganda Busoga Jinja 668 Nalubaale Dam, located on the White Nile north of >1954 Uganda 10 x Jinja and Lake Victoria. AF 5 H Uganda Busoga Jinja Man standing in front of large termite mound. >1954 x Uganda 11 AF 5 H Uganda Busoga Jinja Trio of men seated on shore of Victoria Nile (branch of >1954 Uganda 12 x White Nile), fishing. AF 5 H Uganda Busoga Jinja 669 Boys fishing in the Victoria Nile near Nalubaale Dam. >1954 Uganda 13 x AF 5 H Uganda Busoga Jinja Man examining bicycle on edge of water. -

Local Government Councils' Perfomance and Public

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 Lillian Muyomba-Tamale Godber W. Tumushabe Ivan Amanigaruhanga Viola Bwanika-Semyalo Emma Jones 1 ACODE Policy Research Series No. 45, 2011 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/10 Lillian Muyomba-Tamale Godber W. Tumushabe Ivan Amanigaruhanga Viola Bwanika-Semyalo Emma Jones i LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA MUKONO DISTRICT COUNCIL SCORE-CARD REPORT 2009/2010 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Muyomba-Tamale, L., (2011). Local Government Councils’ Performance and public Service Delivery in Uganda: Mukono District Council Score-Card Report 2009/10. ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 45, 2011. Kampala. © ACODE 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this general exemption. -

Political Theologies in Late Colonial Buganda

POLITICAL THEOLOGIES IN LATE COLONIAL BUGANDA Jonathon L. Earle Selwyn College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It does not exceed the limit of 80,000 words set by the Degree Committee of the Faculty of History. i Abstract This thesis is an intellectual history of political debate in colonial Buganda. It is a history of how competing actors engaged differently in polemical space informed by conflicting histories, varying religious allegiances and dissimilar texts. Methodologically, biography is used to explore three interdependent stories. First, it is employed to explore local variance within Buganda’s shifting discursive landscape throughout the longue durée. Second, it is used to investigate the ways that disparate actors and their respective communities used sacred text, theology and religious experience differently to reshape local discourse and to re-imagine Buganda on the eve of independence. Finally, by incorporating recent developments in the field of global intellectual history, biography is used to reconceptualise Buganda’s late colonial past globally. Due to its immense source base, Buganda provides an excellent case study for writing intellectual biography. From the late nineteenth century, Buganda’s increasingly literate population generated an extensive corpus of clan and kingdom histories, political treatises, religious writings and personal memoirs. As Buganda’s monarchy was renegotiated throughout decolonisation, her activists—working from different angles— engaged in heated debate and protest. -

Aruwe Needs Assessment for Land Issues in Kyankwanzi District 2018

A DOCUMENTATION OF FINDINGS OF LAND RELATED CHALLENGES AMONG RURAL WOMEN IN KYANKWANZI DISTRICT AND PROMISING PRACTICES RELATED TO STRENGTHENING WOMEN'S LAND RIGHTS “There have been a few things in my life that have had a more genial effect on my mind than the possession of a piece of land,” Harriet Martineau 1802-1876, first female sociologist. MAY 2018 1 1.0. Introduction This document presents the findings of land related challenges among rural farmers in Kyankwanzi district and promising practices related to strengthening women's land rights. The data collection exercise conducted by Action for Rural Women’s Empowerment (ARUWE) Uganda in partnership with Emerge Poverty Free/Comic Relief Uk. ARUWE sought to establish community knowledge in land governance structures, land ownership and documentation as well as gender and land ownership. Data was collected using a structured questionnaire. The sample included 346 females and 68 males making a total of 414. The exercise was conducted in Kitabona, Nkandwa and Gayaza Sub counties in Kyankwanzi district. 1.1. About the organization. Action for Rural Women’s Empowerment (ARUWE) is a grassroots non- profit organization working with marginalized groups of people especially rural women and children in Uganda. ARUWE operates in Wakiso, Kiboga, Kyankwanzi, Mpigi, Nakapiripirit and Sembabule districts focusing on eliminating discriminative practices that inhibit women’s potential in the social, economic and civic sectors. ARUWE envisions a world in which women and children realize their full social, economic and civic potential and our mission is to empower women to manage their socio-economic development processes through strengthening community participation, advocacy and service delivery. -

The Restoration of the Buganda Kingship

CMIWORKINGPAPER Kingship in Uganda The Role of the Buganda Kingdom in Ugandan Politics Cathrine Johannessen WP 2006: 8 Kingship in Uganda The Role of the Buganda Kingdom in Ugandan Politics Cathrine Johannessen WP 2006: 8 CMI Working Papers This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 ISSN 0805-505X ISBN 82-8062-147-4 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/publications Indexing terms Politics History Buganda Uganda Project title The legal and institutional context of the 2006 elections in Uganda Project number 24076 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2. HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS: THE KABAKA AND HIS PEOPLE .......................................... 2 2.1 TOWARDS INDEPENDENCE......................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 THE 1966 CRISIS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 BUGANDA AND THE NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT (NRM) ............................................................ 5 3. THE CONSTITUTION-MAKING PROCESS: THE RESTORATION OF THE BUGANDA KINGSHIP ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Land Politics and Conflict in Uganda: a Case Study of Kibaale District, 1996 to the Present Day

7 Land Politics and Conflict in Uganda: A Case Study of Kibaale District, 1996 to the Present Day John Baligira Introduction This chapter examines how the interplay between politics and the competing claims for land rights has contributed to conflict in Kibaale district since 1996. It considers the case of Kibaale district as unique. First, as a result of the 1900 Buganda Agreement, 954 square miles of land (mailo land in Luganda language) which constituted 58 per cent of the total land in Buyaga and Bugangaizi counties of present Kibaale district was allocated by the British colonialists to chiefs and notables from Buganda. It is unique because there is no other district in Uganda, where most of the land is statutorily owned by people from outside that district. Second, people from elsewhere migrated massively to Kibaale district to the extent that they constitute about 50 per cent of the total population. No other district in Uganda has so far hosted new settlers constituting such a high percentage of its population. The chapter argues that the massive immigration and acquisition of land, the existence of competing land rights regimes, and the politicization of claims for land rights have contributed to conflict in Kibaale district (see map 1). 7- Land Politics.indd 157 28/06/2017 22:54:21 158 Peace, Security and Post-Conflict Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa Map 7.1: Location of Kibaale district in Uganda Source: Makerere University Cartography Office, Geography Department, 2010 The ownership of mailo land in Buyaga and Bugangaizi counties by mostly Baganda was vehemently opposed by the Banyoro who considered themselves the original land owners.