Final Report | Version 27/07/2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoria 2003 ESPANOL

ACTIVIDAD 2003 Edición Autoritat del Transport Metropolità c/ Muntaner, 315-321 08021 Barcelona Teléfono +34 93 362 00 20 Fax +34 93 362 00 22 e-mail: [email protected] web: www.atm-transmet.org Depósito legal: B34284-2004 Impresión: Estudi 6 Diseño y Maquetación: www.aidcreativos.com Barcelona, julio de 2004 2 CAPÍTULO 1 PRESENTACIÓN DEL CONSORCIO 7 1 ADMINISTRACIONES INTEGRANTES DE LA ATM 9 2 ÓRGANOS DE GOVIERNO, ASESORAMIENTO Y CONSULTA 10 3 ESTRUCTURA ORGANIZATIVA Y RECURSOS HUMANOS 18 CAPÍTULO 2 ACTUACIÓN EN EL EJERCICIO 2003 21 1 PLANIFICACIÓN DE INFRAESTRUCURAS Y SERVICIOS 23 1.1 Informe anual de seguimiento del PDI 2001-2010 23 1.2 Desarrollo de actuaciones del PDI 29 1.3 Estudios de viabilidad derivados del PDI 30 1.4 Otros estudios y proyectos de trazado 30 1.5 Plan de Servicios de Transporte Público Colectivo 2005 31 2 GESTIÓN DE PROYECTOS 36 2.1 Tranvía Diagonal - Baix Llobregat 36 2.2 Tranvía Sant MartíBesòs 40 3 SISTEMA TARIFARIO INTEGRADO 43 3.1 Ventas y utilización del Sistema Tarifario Integrado (STI) 44 3.2 Tarifa media ponderada 47 3.3 Índice de intermodalidad 48 4 SERVICIO DE TRANSPORTE PÚBLICO INTERURBANO NOCTURNO 49 5 ACTUACIONES CONTRA EL FRAUDE 50 6 ATENCIÓN AL CIUDADANO 52 7 CENTRO DE INFORMACIÓN TransMet 53 8 PLANOS DE LA RED FERROVIARIA INTEGRADA 54 9 PROGRAMA DE MEJORA DE LA FLOTA Y DE SU ACCESSIBILIDAD 56 10 TECNOLOGÍAS DE SISTEMAS DE TRANSPORTE 57 10.1 Gestión de la Integración Tarifaria (SGIT) 57 10.2 Proyecto de Tarjeta XIP Sin Contacto 57 10.3 Sistema de Ayuda a la Explotación (SAE) 58 10.4 Empresa -

Report Report INTRODUCTION

Report Report INTRODUCTION The efforts the Catalan government is making to extend the public transport network to new points of the territory and improve the quality of the service have made a notable contribution to the increase in demand, especially in the second half of 2010. For example, in the sphere of the integrated fare system for the Barcelona area a total of 922.33 million journeys were recorded for 2010, 0.9% more than the previous year, thanks largely to the increase in the number of journeys by Metro, a 5.4% increase over 2009. Moreover, this upward tendency in the number of journeys made by public transport has been confirmed in the first quarter of 2011, and the forecasts for the close of the year LLUÍS RECODER I MirAllES already point to a record annual figure. Councillor for Territory and Sustainability and Chairman of the This recovery of demand is partly due to the set of measures taken to improve the infra- Metropolitan Transport Authority structure which the Catalan government is promoting in order to extend the public transport network and bring it to new centres of population, thus substantially broadening its area of coverage. It was in 2010 that new sections of the Metro came into operation, such as L9/L10 between Gorg and La Sagrera, L5 between Horta and Vall d’Hebron, and L2 between Pep Ventura and Badalona Pompeu Fabra. It was in the same year that Ferrocarrils de la Generalitat opened the station at Volpelleres near Sant Cugat del Vallès. In the field of road public transport various bus lines have been modified and extended to adapt their routes to the new needs for access to strategic facilities and other points where a large number of journeys are concentrated. -

Sea Water Intrusion in Coastal Carbonate Formations in Catalonia, Spain E

SEA WATER INTRUSION IN COASTAL CARBONATE FORMATIONS IN CATALONIA, SPAIN E. Custodio, Dr. Ind. Eng. M. Pascual, Geologist X. Bosch, Geologist A. Bayo, Geologist International Course on Groundwater Hydrology, Universitat Polit~cnica de Catalunya and Eastern Pyrenees Authority. Barcelona. Spain. Abstract Extensive carbonate formations are found along the Southern coast of Catalonia, in NE Spain. High population density and elevated water demand in small coastal basins with permanently dry creeks has put a great pressure to get water from limestones. Most wells exploit brackish water or became salt water polluted soon. Preliminary surveys show the existence of a very permeable carbonate formation near the coast that changes into a low permeability aquifer where distance to the coast line increases. In some instances cation exchange appears and shows the advancing nature of the salt water front. Two main areas are discussed, the Vandellos massif in which some deep observation wells have been drilled and the Southern part of the Garraf massif, where salinity problems are acute, and show a wide variation with areal situation. In these sites a thin fresh water layer floats on saline water, the mixing zone presenting a thickness varying from one site to another. Carbonate minerals saturation indexes are discussed. Introduction Recent interest in research into the hydrochemical processes at work in mixing zones where fresh water and salt water come into contact in coastal aquifers has given rise to a series of publications by authors 147 all over the world: Hanshaw and Back (19791; Back et al. (19791, Maga ritz et al., (1980l; Back and Hanshaw (19831; Herman and Back (!9841; Magaritz and Luzier (1985); Mercado (19851; Tulipano and Fidelibus (1986); Custodio et al. -

Loire Valley by Rail

Loire Valley by Rail Train Seats Travel On all legs of the journey you have reserved seat and carriage numbers which are shown clearly on Passports your ticket. You may need to renew your British Passport if you are travelling to an EU country. Please ensure your passport is less than 10 years old (even if it has 6 months or more left on it) and has at least 6 Baggage months validity remaining from the date of travel. As with most trains, passengers are responsible for EU, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino carrying baggage onto and off the train. Baggage and Swiss valid national identification cards are also can be stored on overhead shelves or at the acceptable for travel. For more information, please entrance to the carriages. Trollies are available at St visit: passport checker Pancras and Lille, but bags do need to be carried on to the platform. Porters are sometimes but not always available at St Pancras. Visas As a tourist visiting from the UK, you do not need a Travel Editions recommends a luggage delivery visa for short trips to most EU countries, Iceland, service called thebaggageman, where your suitcase Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. You will be can be picked up from your home before departure able to stay for up to 90 days in any 180-day period. and delivered straight to your hotel; therefore For all other passport holders please check the visa removing the worry about carrying your cases onto requirements with the appropriate embassy. and off the trains. For further information, please check here: travel to the EU For further information: http://www.thebaggageman.com For all other passport holders please check the visa requirements with the appropriate embassy. -

The Development of the Association Of

THE DEVELOPMENT OF T HE ASSOCIATION OF FO R E S T R Y OWNERS IN ´EL MASSIS DEL GARRAF´ FOR THE E N E R G E T I C EXPLOITATION OF FORE ST BIOMASS. 6TH UPC INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON SUSTAINABLE TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT VILANOVA I LA GELTRÚ – 2013 International Group 1: Oriol Costa Echaniz Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain Brandon Summers Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain Stephan Maier Graz University of Technology Graz, Austria Stina Tang The Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden Nick Kerckhaert Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................. ¡Error! Marcador no definido. Table of contents ........................................................................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Results ............................................................................................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. Discussion ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................ -

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology

Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Sebastià Herreros i Agüí Abstract Modernism (Modern Style, Modernisme, or Art Nouveau) was an artistic and cultural movement which flourished in Europe roughly between 1880 and 1915. In Catalonia, because this era coincided with movements for autonomy and independence and the growth of a rich bourgeoisie, Modernism developed in a special way. Differing from the form in other countries, in Catalonia works in the Modern Style included many symbolic elements reflecting the Catalan nationalism of their creators. This paper, which follows Wladyslaw Serwatowski’s 20 ICV presentation on Antoni Gaudí as a vexillographer, studies other Modernist artists and their flag-related works. Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Josep Llimona, Miquel Blay, Alexandre de Riquer, Apel·les Mestres, Antoni Maria Gallissà, Joan Maragall, Josep Maria Jujol, Lluís Masriera, Lluís Millet, and others were masters in many artistic disciplines: Architecture, Sculpture, Jewelry, Poetry, Music, Sigillography, Bookplates, etc. and also, perhaps unconsciously, Vexillography. This paper highlights several flags and banners of unusual quality and national significance: Unió Catalanista, Sant Lluc, CADCI, Catalans d’Amèrica, Ripoll, Orfeó Català, Esbart Català de Dansaires, and some gonfalons and flags from choral groups and sometent (armed civil groups). New Banner, Basilica of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 506 Catalan Modernism and Vexillology Background At the 20th International Conference of Vexillology in Stockholm in 2003, Wladyslaw Serwatowski presented the paper “Was Antonio Gaudí i Cornet (1852–1936) a Vexillographer?” in which he analyzed the vexillological works of the Catalan architectural genius Gaudí. -

Agricultural and Horticultural Halls and Annexes

www.e-rara.ch International exhibition. 1876 official catalogue Agricultural and horticultural halls and annexes United States Centennial Commission Philadelphia, 1876 ETH-Bibliothek Zürich Shelf Mark: Rar 20263: 3-4 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-78195 Spain. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement. -

Catalonia Accessible Tourism Guide

accessible tourism good practice guide, catalonia 19 destinations selected so that everyone can experience them. A great range of accessible leisure, cultural and sports activities. A land that we can all enjoy, Catalonia. © Turisme de Catalunya 2008 © Generalitat de Catalunya 2008 Val d’Aran Andorra Pirineus Costa Brava Girona Lleida Catalunya Central Terres de Lleida Costa de Barcelona Maresme Costa Barcelona del Garraf Tarragona Terres Costa de l’Ebre Daurada Mediterranean sea Catalunya Index. Introduction 4 The best destinations 6 Vall de Boí 8 Val d’Aran 10 Pallars Sobirà 12 La Seu d’Urgell 14 La Molina - La Cerdanya 16 Camprodon – Rural Tourism in the Pyrenees 18 La Garrotxa 20 The Dalí route 22 Costa Brava - Alt Empordà 24 Vic - Osona 26 Costa Brava - Baix Empordà 28 Montserrat 30 Maresme 32 The Cister route 34 Garraf - Sitges 36 Barcelona 38 Costa Daurada 40 Delta de l’Ebre 42 Lleida 44 Accessible transport in Catalonia 46 www.turismeperatothom.com/en/, the accessible web 48 Directory of companies and activities 49 Since the end of the 1990’s, the European Union has promoted a series of initiatives to contribute to the development of accessible tourism. The Catalan tourism sector has boosted the accessibility of its services, making a reality the principle that a respectful and diverse society should recognise the equality of conditions for people with disabilities. This principle is enshrined in the “Barcelona declaration: the city and people with disabilities” that to date has been signed by 400 European cities. There are many Catalan companies and destinations that have adapted their products and services accordingly. -

2021 UCI Trials World Championships Must Register All Persons Included in the Delegation Using the Following Form

Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Rules .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Selection of Participants ............................................................................................................................ 4 4. Riders Categories ....................................................................................................................................... 4 5. Competition Format .................................................................................................................................. 4 National Team Competition .......................................................................................................................... 6 6. Registration and Riders’ Confirmation ...................................................................................................... 7 Online registration ......................................................................................................................................... 7 7. Riders confirmation ................................................................................................................................... 8 8. Delegation Accreditation .......................................................................................................................... -

WP2.2Barcelona FINAL

The city of marvels? Multiple endeavours towards competitiveness in Barcelona Pathways to creative and knowledge-based regions ISBN: 978-90-75246-56-8 Printed in the Netherlands by Xerox Service Center, Amsterdam Edition: 2007 Cartography lay-out and cover: Puikang Chan, AMIDSt, University of Amsterdam All publications in this series are published on the ACRE-website http://www2.fmg.uva.nl/acre and most are available on paper at: Dr. Olga Gritsai, ACRE project manager University of Amsterdam Amsterdam institute for Metropolitan and International Development Studies (AMIDSt) Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies Nieuwe Prinsengracht 130 NL-1018 VZ Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel. +31 20 525 4044 +31 23 528 2955 Fax +31 20 525 4051 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © Amsterdam institute for Metropolitan and International Development Studies (AMIDSt), University of Amsterdam 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced in any form, by print or photo print, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. The city of marvels? Multiple endeavours towards competitiveness in Barcelona Pathways to creative and knowledge-based regions ACRE report 2.2 Montserrat Pareja Eastaway Joaquin Turmo Garuz Marc Pradel i Miquel Lídia García Ferrando Montserrat Simó Solsona Maite Padrós (language revision) Accommodating Creative Knowledge – Competitiveness of European Metropolitan Regions within the Enlarged Union Amsterdam 2007 AMIDSt, University of Amsterdam ACRE ACRE is the acronym for the international research project Accommodating Creative Knowledge – Competitiveness of European Metropolitan Regions within the enlarged Union. The project is funded under the priority 7 ‘Citizens and Governance in a knowledge-based society within the Sixth Framework Programme of the EU (contract no. -

Archives of the Crown of Aragon Catalogue of Publications of the Ministry: General Catalogue of Publications: Publicacionesoficiales.Boe.Es

Archives of the Crown of Aragon Catalogue of Publications of the Ministry: www.mecd.gob.es General Catalogue of Publications: publicacionesoficiales.boe.es Edition 2018 Translation: Communique Traducciones MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, CULTURE AND SPORTS Published by: © TECHNICAL GENERAL SECRETARIAT Sub-Directorate General of Documentation and Publications © Of the texts and photographs: their authors NIPO: 030-18-036-7 Legal Deposit: M-13391-2018 Archives of the Crown of Aragon 700th anniversary of the creation of the Archive of the Crown of Aragon (ACA) (1318) United Nations Santa Fe Capitulations United Nations Celebrated in association with UNESCO Educational, Scientific and Inscribed on the Register in 2009 Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Memory of the World Cultural Organization Index 1. History .......................................................................................................... 7 2. Current Locations ..................................................................................... 21 3. Board of Trustees ..................................................................................... 25 4. European Heritage Label and UNESCO Memory of the World Register ........................................................................................................ 28 5. Documents ................................................................................................. 32 Real Cancillería (Royal Chancery) ....................................................... 32 Consejo de Aragón (Council of -

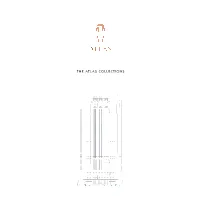

The Atlas Collections

THE ATLAS COLLECTIONS Dear Guests, Welcome to ATLAS - a labour of love that honours my grandfather, CS Hwang, the late founder of Parkview Group, and the beautiful space he created in which ATLAS resides. It is our hope that your experience at ATLAS reflects the passion and attention that has gone into every aspect of its creation. A grand and beautiful space, we invite you to unwind, enjoy, celebrate and indulge as our talented and dedicated ATLAS team makes you feel most welcome and at home. The ATLAS Collections feature two of the world’s most remarkable physical collections of Gin and Champagne. Building the ATLAS Collections was a monumental task which took over two years to curate and assemble. We are also delighted to feature a selection of rare and exceptional still wines and whiskies from my own family’s private cellar, which for the first time since its inception almost 40 years ago, has been opened especially for our guests at ATLAS. Building upon the modest collection of wines started by my grandfather, the Parkview Family Cellar found a permanent home in 1989 with the opening of the Parkview Group’s flagship property, Hong Kong Parkview. Initially consisting of a small collection of 50 bottles of right bank Bordeaux wines, the collection grew steadily under the stewardship of my uncle, George Wong, and his son Alex. By 2000, the collection was at 3,000 bottles and has now expanded beyond the right bank to other regions in France and the rest of the world. Currently, the collection stands at 50,000 bottles of fine wine and over 10,000 bottles of whiskey acquired through reputable merchants, auctions, and numerous trips to the wineries and distilleries where suppliers have now become close friends, ensuring that the family always has access to the finest and rarest bottles.