Troy Spring State Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT of ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Procurement Section 3800 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS#93 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Procurement Section 3800 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS#93 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 February 19, 2016 Addendum To: DEP RFI No. 2016033C, entitled “Point of Sale System” The Department hereby answers questions posed by prospective Respondents. Unless expressly indicated, these answers do not amend the terms of the Request for Information (RFI). The Department hereby answers the following questions: 1. Is managing the schedule of reservations within the scope of this project, or is this simply for accepting payment for the reservations? Answer #1: Neither of these items is within the scope of this project. The POS will need to function with the existing reservation system on contract, ReserveAmerica, which already schedules and accepts payments for the reservations. 2. Can you provide a list of current vendors that require integration, as well as the intended purpose of the integration? Answer #2: The current vendors that the POS System will need to integrate with are the ReserveAmerica reservation system and the State Contract for Credit Card Processing Services with Bank of America. The intended purpose is for the Department to provide a real-time dashboard, showing data related to revenue, attendance, annual pass use, etc. at a Park, District and Statewide level. 3. Is there an expected method of integration to the State Finance and Accounting systems? Answer #3: Yes, at minimum, data will need to “connect” to the State Finance and Accounting systems through an electronic data file (i.e. Excel or CSV document with specific formatting). Data will need to be integrated at minimum on a monthly basis, but the Department’s ultimate goal is to have real-time data available. -

Florida Greenway and Trail Designations Sorted by Name

Florida Greenway And Trail Designations Sorted by Name DESCRIPTION COUNTY(S) TYPE ACRES MILES NUMBER DATE Addison Blockhouse Historic State Park Volusia Site 147.92 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alafia River Paddling Trail Hillsborough Paddling Trail 13.00 Grandfather 12/8/1981 Alafia River State Park Hillsborough Site 6,314.90 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park Leon Site 1,168.98 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Allen David Broussard Catfish Creek Preserve Polk Site 8,157.21 OGT-DA0079 12/9/2015 Amelia Island State Park Nassau Site 230.48 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Anastasia State Park St. Johns Site 1,592.94 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Anclote Key Preserve State Park Pasco, Pinellas Site 12,177.10 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Apalachee Bay Maritime Heritage Paddling Trail Wakulla Paddling Trail 58.60 OGT-DA0089 1/3/2017 Apalachicola River Blueway Multiple - Calhoun, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Paddling Trail 116.00 OGT-DA0058 6/11/2012 Jackson, Liberty Apalachicola River Paddling Trails System Franklin Paddling Trail 100.00 OGT-DA0044 8/10/2011 Atlantic Ridge Preserve State Park Martin Site 4,886.08 OGT-DA0079 12/9/2015 Aucilla River Paddling Trail Jefferson, Madison, Taylor Paddling Trail 19.00 Grandfather 12/8/1981 Avalon State Park St. Lucie Site 657.58 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Bagdad Mill Santa Rosa Site 21.00 OGT-DA0051 6/6/2011 Bahia Honda State Park Monroe Site 491.25 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Bald Point State Park Franklin Site 4,875.49 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Bayard and Rice Creek Conservation Areas Clay, Putnam Site 14,573.00 OGT-DA0031 6/30/2008 Bayshore Linear -

Ichetucknee Springs & River

http://santaferiversprings.com/ • Bonn, M. A. and F. W. Bell. Economic impact of selected Florida springs on surrounding local areas. Florida Department of Environmental Protection, 2003 (Ichetucknee, Wakulla, Homosassa, Blue springs). • Bonn, M.A. Visitor profiles, economic impacts, and recreational aesthetic values associated with eight priority Florida springs located in the St. Johns River Water Management District. St. Johns River Water Management District, Palatka, FL, 2004 (Silver Glen, Silver, Alexander, Apopka, Bugg, Ponce de Leon, Gemini, Green springs). • Foster, C. Valuing preferences for water quality improvement in the Ichetucknee Springs System: A Case Study from Columbia County, FL. Master Thesis, University of Florida, 2008. • Huth, W.L. and O.A. Morgan. Measuring the willingness to pay for cave diving. Marine Resource Economics vol. 26, pp 151-166,2011 (Wakulla Springs). • Morgan, O.A. and W.L. Huth. Using revealed and stated preference data to estimate the scope and access benefits associated with cave diving. Resource and Energy Economics vol. 33, pp. 107-118, 2011 (Blue Spring, Jackson County, Florida). • Knight, R. Ichetucknee Springs & River: A Restoration Action Plan. Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute, 2012. • Shrestha R.L., Alavalapati, J.R.R., Stein T.V., Carter, D.R., and C.B. Denny. Visitor Preferences and Values for Water-Based Recreation: A Case Study of the Ocala National Forest. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 34(3), 547 – 559, 2002 (Sweetwater, Silver Glen, Juniper, Salt Springs). Credit: map is copied from http://www.saveoursuwannee.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/florida-spreings1.jpg Tallahassee Jacksonville Lake City High Springs Gainesville Ocala Orlando Multipliers for the North-Central Florida Study Area Indirect Output Employment Labor Value Added Expenditure Item(s) IMPLAN Sector Business (Revenue) (jobs/M$) Income (GDP) Taxes 324. -

Florida's Economy

How Springs Invigorate Florida’s Economy Florida has wonderful water resources. Our seashores, terms, water resources generate a lot of money for our estuaries, springs, rivers, lakes, and wetlands are a state. Take, for instance, the springs in our state parks. big reason why our state is such a great place for In 2019, springs in Florida’s state parks were visited by people and all living things. Springs are a unique and more than 3.9 million visitors, who spent over $350 valuable ecosystem to Florida. Every year, millions of million in local economies, supporting 4,885 jobs. people are drawn to our state’s springs for recreation and employment. In fact, when you put it in economic 4 11 9 15 17 8 21 16 7 13 5 3 10 14 12 1 2 6 Florida Water Management Districts 19 18 Northwest Florida 20 Suwannee River St. Johns River Southwest Florida South Florida * Direct Economic Impact (DEI): The amount of new dollars spent in a local economy by non-local park visitors and park operations. 1. Blue Spring State Park 8. Lafayette Blue Springs 15. Suwannee River State Park (Volusia County) State Park (Hamilton, Madison, & 561,219 annual park attendance (Lafayette County) Suwannee counties) $48.8 million DEI* 17,671 annual park attendance 45,465 annual park attendance 572 total jobs supported $1.8 million DEI* $4.2 million DEI* 26 total jobs supported 59 total jobs supported 2. De Leon Springs State Park (Volusia County) 9. Madison Blue Spring 16. Troy Spring State Park 243,285 annual park attendance State Park (Lafayette County) $21.4 million DEI* (Madison County) 6,450 annual park attendance 300 total jobs supported 24,558 annual park attendance $0.6 million DEI* $2.2 million DEI* 9 total jobs supported 3. -

Economic Contributions and Ecosystem Services of Springs in the Lower Suwannee and Santa Fe River Basins of North-Central Florida

Economic Contributions and Ecosystem Services of Springs in the Lower Suwannee and Santa Fe River Basins of North-Central Florida Tatiana Borisova, PhD, Alan W. Hodges, PhD, and Thomas J. Stevens, PhD University of Florida, Food & Resource Economics Department May 29, 2014 Manatees in Manatee Springs (Credit: Mark Long) 1 Economic Contributions and Ecosystem Services of Springs in the Lower Suwannee and Santa Fe River Basins of North-Central Florida Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the project funding sources for their support: The Wildlife Foundation of Florida, Inc. (through Protect Florida Springs Tag Grant program) and Save Our Suwannee, Inc. Project advisors are Annette Long, President, Save Our Suwannee, and Stacie Greco, Water Conservation Coordinator, Alachua County Environmental Protection Department. Thanks to over 20 local business owners, park managers and local government representatives who gave interviews (via phone or over e-mail) and provided information about the springs in the region. In addition, background research and editorial services were provided by Sara Wynn. We are also grateful to Mark and Annette Long for providing photos of springs to be used as illustrations in this report, and we appreciate Jim Hatchitt, Alachua County Environmental Protection Department, for developing the maps of our study region. Table of Contents Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction -

Senate Districts (This Compilation Was Produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019)

Florida State Parks FY 2017-18 Data by 2019 Senate Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019) . Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.4 billion direct economic impact • $158 million in sales tax revenue • 33,587 jobs supported • Over 28 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park Senate Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Broxson, Doug 6 50,681,138 708 614,002 Big Lagoon State Park 12,155,746 170 141,517 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,301,348 214 188,630 Blackwater River State Park 6,361,036 89 75,848 Perdido Key State Park 12,739,427 178 157,126 Tarkiln Bayou Preserve State Park 3,239,973 45 40,164 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 883,608 12 10,717 2 Gainer, George B. 12 196,096,703 2,747 2,340,983 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 Deer Lake State Park 1,654,544 23 19,939 Eden Gardens State Park 3,298,681 46 39,601 Falling Waters State Park 5,761,074 81 67,225 Florida Caverns State Park 12,217,659 171 135,677 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,896,093 111 88,633 Grayton Beach State Park 20,250,255 284 236,181 Henderson Beach State Park 38,980,929 546 476,303 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 4,745,495 66 57,194 St. Andrews State Park 73,408,034 1,028 894,458 Three Rivers State Park 3,465,975 49 39,482 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 21,639,586 303 254,586 3 Montford, Bill 25 124,181,920 1,739 1,447,446 Bald Point State Park 2,238,898 31 26,040 Big Shoals State Park 2,445,527 34 28,729 Constitution Convention Museum State Park 478,694 7 5,309 Econfina River State Park 1,044,631 15 12,874 Forest Capital Museum State Park 1,064,499 15 12,401 John Gorrie Museum State Park 542,575 8 4,988 Lake Jackson Mounds Archeological State Park 2,440,448 34 27,221 Lake Talquin State Park 1,236,157 17 14,775 Letchworth-Love Mounds Archeological State Park 713,210 10 8,157 Maclay Gardens State Park, Alfred B. -

Florida State Parks Data by 2021 Senate Districts

Florida State Parks FY 2019-20 Data by 2021 Senate District s This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation . FloridaStateParksFoundation.org . Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.2 billion in direct impact to Florida’s economy • $150 million in sales tax revenue • 31,810 jobs supported • 25 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park Senate Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Broxson, Doug 6 57,724,473 809 652,954 Big Lagoon State Park 10, 336, 536 145 110,254 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 18, 971, 114 266 218, 287 Blackwater River State Park 7, 101, 563 99 78,680 Perdido Key State Park 17, 191, 206 241 198, 276 Tarkiln Bayou Preserve State Park 3, 545, 446 50 40, 932 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 578, 608 8 6, 525 2 Gainer, George B. 12 147,736,451 2,068 1,637,586 Camp Helen State Park 3, 133, 710 44 32, 773 Deer Lake State Park 1, 738, 073 24 19, 557 Eden Gardens State Park 3, 235, 182 45 36, 128 Falling Waters State Park 5, 510, 029 77 58, 866 Florida Caverns State Park 4, 090, 576 57 39, 405 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7, 558,966 106 83, 636 Grayton Beach State Park 17, 072, 108 239 186, 686 Henderson Beach State Park 34, 067, 321 477 385, 841 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6, 911, 495 97 78, 277 St. Andrews State Park 41, 969, 305 588 472, 087 Three Rivers State Park 2,916,005 41 30,637 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 19,533,681 273 213, 693 3 Ausley, Loranne 25 91,986,319 1,288 970,697 Bald Point State Park 2, 779, 473 39 30, 621 Big Shoals State Park 1 , 136, 344 16 11, 722 Constitution Convention Museum State Park 112, 750 2 698 Econfina River State Park 972, 852 14 11, 198 Forest Capital Museum State Park 302, 127 4 2, 589 John Gorrie Museum State Park 269, 364 4 2, 711 Lake Jackson Mounds Archeological State Park 2, 022, 047 28 20, 627 Lake Talquin State Park 949, 359 13 8, 821 Letchworth-Love Mounds Archeological State Park 573, 926 8 5, 969 Maclay Gardens State Park, Alfred B. -

Designated Greenways and Trails by County

Florida Greenway And Trail Designations Sorted by County COUNTY(S) NAME TYPE ACRES MILES NUMBER DATE 13 counties St. Johns River Blueway Paddling Trail 310 OGT-DA0065 10/17/2013 Alachua Devil's Millhopper Geological State Park Site 66.71 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alachua Dudley Farm Historic State Park Site 327.44 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alachua O'Leno State Park Site 1732.46 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alachua Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park Site 21659.75 OGT-DA0082 1/21/2016 Alachua Potano Paddling Trail Paddling Trail 12 OGT-DA0037 4/14/2009 Alachua River Rise Preserve State Park Site 4481.73 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alachua San Felasco Hammock Preserve State Park Site 7086.06 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Alachua Santa Fe River Paddling Trail Paddling Trail 26 Grandfather 12/8/1981 Baker Pinhook Swamp Purchase Unit Site 40025 OGT-DA0002 6/15/2001 Baker St. Mary's River Paddling Trail Paddling Trail 59 Grandfather 12/8/1981 Baker Weyerhauser-FNST Trail 17.6 OGT-DA0008 10/24/2003 Bay Camp Helen State Park Site 189.93 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Bay Gayle's Trails Panama City Beach Trail 8 OGT-DA0047 5/26/2011 Bay Pine Log State Forest - St. Joe Trail - FNST Segment Trail 6.091 Grandfather 6/26/1990 Bay St. Andrews State Park (includes Shell Island) Site 1167.08 OGT-DA0069 8/13/2014 Bay, Hamilton Econfina Creek Paddling Trail Paddling Trail 22 Grandfather 12/8/1981 Bay, Walton Watersound Trail Trail 5.25 OGT-DA0075 3/25/2015 Brevard Indian River Lagoon Preserve State Park Site 544.08 OGT-DA0077 6/5/2015 Brevard Sebastian Inlet State Park Site 971.01 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Brevard, Volusia East Central Regional Rail Trail Trail 50.8 OGT-DA0071 12/3/2015 Broward Central City Linear Park Trail Trail 2.5 OGT-DA0025 2/20/2007 Broward Hugh Taylor Birch State Park Site 175.24 OGT-DA0003 1/22/2002 Broward John U. -

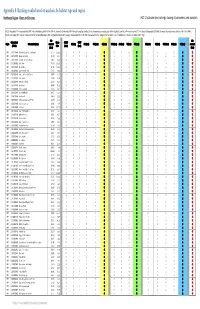

Freshwater Priority Resources

Appendix B. Ranking results based on analysis, by habitat type and region. Northwest Region ‐ Rivers and Streams HUC‐12 sub‐watershed rankings, showing all parameters used in analysis. ACCESS = Accessibility; RT = Recreational Trails; GFBWT = Great Florida Birding & Wildlife Trail; POP = Population w/in 50‐mile radius; FHO = Fishing & Hunting Opportunities; SE = Socio‐Economic Importance (category); WSM = Weighted Stream Miles; AFA = Avian Focus Areas; TE = Threatened, Endangered, & SGCN Wildlife Occurence (Freshwater Forested Wetlands); FW = Fish & Wildlife Populations (category); RFB = Riparian ‐ Freshwater Buffer; IW = Impaired Waterbodies; WRD = Weighted Road Density; IAP = Category 1 Invasive Aquatic Plants; ME ‐ FWF = Management Emphasis (category); Priority Ranks: 1 = Low; 2 = Medium Low; 3 = Medium; 4 = Medium High; 5 = High Sub- Sub- Sub-watershed Stream ACCESS GFBWT Region Sub-watershed (Name) watershed RT (Rank) POP (Rank) FHO (Rank) SE (Rank) WSM (Rank) AFA (Rank) TE (Rank) FW (Rank) RFB (Rank) IW (Rank) WRD (Rank) IAP (Rank) ME (Rank) watershed (HUC-12) Miles (Rank) (Rank) (Acres) (Rank) NW 031300110804 East River-Apalachicola River Frontal 39,713 169.61 3451 5 5 55 4 5 23254 5 NW 031300130504 Blounts Bay Frontal 25,504 81.33 4451 5 5 34 3 5 43224 5 NW 031300130503 Tates Hell Swamp-Cash Creek 20,453 80.20 4252 5 5 33 2 4 52225 5 NW 031403050602 White River 38,530 152.09 3155 5 5 51 5 4 33424 5 NW 031300110803 Brothers River 45,705 139.31 4352 5 5 52 4 5 21243 5 NW 031200011003 Lower St. Marks River 27,372 79.83 3312 5 4 35 -

Environmental Protection Jeanette Nuñez Lt

Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Shawn Hamilton 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Interim Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399 Aug. 13, 2021 The Honorable Ron DeSantis Governor of Florida Plaza Level 05, The Capitol 400 South Monroe Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0001 The Honorable Wilton Simpson, President Florida Senate Room 409, The Capitol 404 South Monroe Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0001 The Honorable Chris Sprowls, Speaker Florida House of Representatives Room 420, The Capitol 402 South Monroe Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0001 Patricia Jameson, Coordinator Florida Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability 111 West Madison, Room 312 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0001 Dear Governor DeSantis, President Simpson, Speaker Sprowls and Coordinator Jameson: The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) holds agreements with 97 Citizen Support Organizations (CSOs). Pursuant to Section 20.058, Florida Statutes, each CSO is required to report information related to its organization, mission and finances to DEP annually by August 1. DEP is required to report by August 15 of each year to the Governor, President of the Senate, Speaker of the House of Representatives and the Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, the information provided by each CSO, including a recommendation with supporting rationale to “continue,” “terminate” or “modify” DEP’s association with each. DEP recommends to “continue” association with 97 CSOs. The enclosed report includes DEP’s recommendations and rationale related to each CSO. The report, supporting documentation and links to their individual websites (if applicable) can be found on DEP’s website at: www.floridadep.gov/comm/comm/content/citizen-support-organizations-reports. -

Reasons to Love Florida: a COUNTY

• ALACHUA • BAKER • BAY • BRADFORD • BREVARD • BROWARD • CALHOUN • CHARLOTTE • CITRUS • CLAY • COLLIER • COLUMBIA • DESOTO • DIXIE • DUVAL • • JEFFERSON • INDIAN RIVER JACKSON • HOLMES • HILLSBOROUGH • HERNANDO HIGHLANDS • HARDEE HENDRY • GULF HAMILTON • GLADES • GILCHRIST • FRANKLIN GADSDEN • FLAGLER ESCAMBIA 67 Reasons To Love Florida: A COUNTY GUIDE OSCEOLA • PALM BEACH • PASCO • PINELLAS • POLK • PUTNAM • ST. JOHNS • ST. LUCIE • SANTA ROSA • SARASOTA • SEMINOLE • SUMTER • SUWANNEE • TAYLOR • UNION • VOLUSIA • WAKULLA • WALTON • WASHINGTON • WALTON • WAKULLA • UNION VOLUSIA • TAYLOR • SEMINOLE SUMTER SUWANNEE • SARASOTA ROSA • SANTA LUCIE JOHNS • ST. • POLK PUTNAM ST. • PINELLAS • PASCO BEACH • PALM OSCEOLA • ORANGE • OKEECHOBEE • OKALOOSA • NASSAU • MONROE • MIAMI-DADE • MARTIN • MARION • MANATEE • MADISON • LIBERTY • LEVY • LEON • LEE • LAKE • LAFAYETTE T rend Florida WELCOME! www.FloridaTrend.com Publisher David G. Denor Executive Editor Mark R. Howard EDITORIAL Writer Janet Ware Managing Editor John Annunziata Welcome to Florida Trend’s newest publication—“67 Reasons ADVERTISING Senior Market Director / Central Florida & North Florida to Love Florida.” Orlando - Treasure Coast - Gainesville - Brevard County Jacksonville - Tallahassee - Panama City - Pensacola Laura Armstrong 321/430-4456 You’ve probably already guessed that those 67 reasons match the Senior Market Director / Tampa Bay Tampa - St. Petersburg - Sarasota - Naples - Ft. Myers number of counties in the State of Florida. For each county, Florida Christine King 727/892-2641 Senior Market Director / South Florida Trend has compiled the most relevant details including population, Miami - Ft. Lauderdale - Palm Beaches density, county seat, major cities, colleges, hospitals, and Andreea Redis-Coste 954/802-4722 Advertising Coordinator transportaton options. Rana Becker 727/892-2642 Since Florida Trend is a business magazine, you won’t be surprised we list the size of the labor force, top industries, and major companies. -

Florida State Park System

SANTA ROSA HOLMES JACKSON ESCAMBIA OKALOOSA Blackwat5er Heritage 14 16 Ponce de Leon Springs Florida Caverns Fort Clinch State Park State Trail State Park 47 Blackwa6ter River State Park 15 17 30 Fernandina Plaza Historic State Park 4 State Park Falling Waters Three Rivers Alfred B. Maclay Gardens 48 Yellow River Marsh 7 WALTON State Park State Park State Park NASSAU Preserve State Park Fred Gannon 29 Letchwort3h-L1ove Mounds George Crady Bridge Fishing Pier State Park Lake Jackson Mounds District 2 49 Rocky Bayou WASHINGTON Archaeological State Park Archaeological State Park 3 State Park 18 Amelia Island State Park 50 Tarkiln Bayou Torreya 41 HAMILTON 13 State Park Suwannee River Big Talbot Island State Park Preserve Eden Gardens GADSDEN State Park 46 State Park Pumpkin Hill Creek 51 State Park Mad4iso0n Blue Preserve State Park JEFFERSON 43 Little Talbot Island State Park 28 LEON Spring Stephen Foster Folk 52 CALHOUN Lake Talquin St. M3ark2s River Culture Center State Park Henderson Beach State Park Preserve State Park MADISON 44 Fort George Island Cultural State Park 53 State Park BAY Big Shoals BAKER State Park Big Lagoon 33 38 DUVAL Yellow Bluff Fort Historic State Park State Park 8 Topsail Hill Natural Bridge Battlefield Suwannee River 54 Perdido Key Preserve State Park 27 Historic State Park Wilderness Trail Oluste4e B5attlefield State Park Deer Lake LIBERTY Edward Ball COLUMBIA 2 19 Wakulla Springs Historic State Park 9 State Park Constitution Convention 34 Grayton Beach Museum State Park State Park Tallahassee-St. Marks 39 SUWANNEE 1 State Park Historic Railroad State Trail Lafayette Blue 60 11 Camp Helen Springs State Park Ichetucknee CLAY WAKULLA 61 Trace 10 State Park 26 42 Ichetucknee 57 ST JOHNS Ochlockonee River Wes Skiles Springs UNION Palatka-to- 12 State Park San Marcos de Apalache 37 State Park Forest Capital Peacock Troy6 S2pring Lake Butler 55 Historic State Park Museum State Park Springs State Trail Palatka-to- GULF State Park Fort Mose Historic State Park State Park O'Leno5 St9ate Park 56 St.