DARK ROOTS CHRISTOPHER NOLAN and NOIR Jason Ney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{DOWNLOAD} Memento and Following Kindle

MEMENTO AND FOLLOWING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Christopher Nolan | 240 pages | 15 Jun 2001 | FABER & FABER | 9780571210473 | English | London, United Kingdom Unlimited acces Film: Memento and Following Book - video Dailymotion Leonard has created an entirely new identity built on a lie, and because his creation is based on a lie, it ultimately leads to a destructive conclusion, which is that he becomes nothing more than Teddy's hitman. Like The Young Man from Following or Robert Angier from The Prestige or Mal from Inception , Leonard has provided himself a comforting lie, and that lie has proven to be his downfall until he finally decides to pursue something that's true—Teddy is using him and so Teddy must be stopped. The cautionary tale in Memento is that Leonard Shelby, despite his unique condition, is universal in how he lies to himself. Nolan isn't opposed to the concept of a lie—he's a storyteller after all. But he's fascinated by how lies are implemented. For Nolan, lies are tools, and sometimes they can be used to benevolent purposes like a magic show in The Prestige or the mind heist in Inception. In Memento , Leonard finds a new lie—that Teddy is responsible for the rape and murder of Leonard's wife—but like all good art, it's a lie that tells the truth. Teddy may not be responsible for Leonard's condition, but his desire to use Leonard as a weapon makes him at least partially responsible for Leonard's predicament. Leonard lies to himself on a tapestry of good intentions; he tells himself he's not a killer. -

John Caglione, Jr

JOHN CAGLIONE, JR. Make-Up Designer IATSE 798 and 706 FILM BROKEN CITY Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: Allen Hughes PHIL SPECTOR Personal Make-Up Artist to Al Pacino Director: David Mamet TOWER HEIST Department Head Director: Brett Ratner ON THE ROAD Special Make-Up Effects Director: Walter Salles Cast: Viggo Mortensen THE SMURFS Department Head Director: Raja Gosnell YOU DON’T KNOW JACK Personal Make-Up Artist to Al Pacino Director: Barry Levinson Nominee: Emmy Award for Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or Movie SALT Department Head Director: Philip Noyce STATE OF PLAY Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: Kevin Macdonald THE DARK KNIGHT Personal Make-Up Artist to Heath Ledger Director: Christopher Nolan Nominee: Academy Award for Best Achievement in Make-Up Nominee: Saturn Award for Best Make-Up 3:10 TO YUMA Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: James Mangold AMERICAN GANGSTER Personal Make-Up Artist to Russell Crowe Director: Ridley Scott THE DEPARTED Department Head Make-Up and Department Head Effects Make-Up Director: Martin Scorsese Cast: Vera Farmiga, Ray Winstone, Kristen Dalton TENDERNESS Department Head Director: John Polson Cast: Russell Crowe, Laura Dern, Jon Foster, Tonya Clarke THE MILTON AGENCY John Caglione, Jr. 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Make-Up Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 798 & 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 4 MY SUPER EX-GIRLFRIEND Department Head Director: Ivan Reitman Cast: Luke Wilson, Anna -

Keith Madden Costume Designer

KEITH MADDEN COSTUME DESIGNER FILM & TELEVISION IRONBANK Director: Dominic Cooke Production Company: FilmNation, 42 & SunnyMarch Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch THE GOOD LIAR Director: Bill Condon Production Company: Giant Films Cast: Helen Mirren, Ian McKellen, Russell Tovey, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson PATRICK MELROSE Director: Edward Berger Production Company: Little Island Productions Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Hugo Weaving Nominated, Best Actor in a TV Movie or Limited Series, Golden Globes (2019) ON CHESIL BEACH Director: Dominic Cooke Production Company: BBC Films Cast: Saoirse Ronan, Billy Howle, Emily Watson Official Selection, London Film Festival (2017) THE CHILD IN TIME Director: Julian Farino Production Company: BBC Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Kelly Macdonald, Stephen Campbell Moore VICEROY’S HOUSE Director: Gurinder Chadha Production Company: BBC Films Cast: Hugh Bonneville, Gillian Anderson, Michael Gambon Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2017) MR. HOLMES LUX ARTISTS | 1 Director: Bill Condon Production Company: Miramax Cast: Ian McKellen, Laura Linney, Philip Davis Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2015) LUX ARTISTS | 2 GOOD PEOPLE Director: Henrik Ruben Genz Production Company: Millennium Films Cast: James Franco, Kate Hudson, Omar Sy THE WOMAN IN BLACK Director: James Watkins Production Company: Cross Creek Pictures Cast: Daniel Radcliffe, Ciarán Hinds, Janet McTeer CENTURION Director: Neil Marshall Production Company: Panthé Pictures International Cast: Michael Fassbender, Dominic West, Olga Kurylenko PERRIER’S BOUNTY Director: Ian Fitzgibbon Production Company: Parallel Film Productions Cast: Gabriel Byrne, Cillian Murphy, Jodie Whittaker Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2009) EDEN LAKE Director: James Watkins Production Company: The Weinstein Company Cast: Michael Fassbender, Kelly Reilly, Jack O’Connell ARTISTS WEBSITE LUX ARTISTS | 3. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Batman Begins Free

FREE BATMAN BEGINS PDF Dennis O'Neil | 305 pages | 15 Jul 2005 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345479464 | English | New York, United States It's Time to Talk About How Goofy 'Batman Begins' Is | GQ As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we have six shows to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. Watch the video. When his parents are killed, billionaire playboy Bruce Wayne relocates to Asia, where he is mentored by Henri Ducard and Batman Begins Al Ghul in how to fight evil. When learning about the plan to wipe out evil in Gotham City by Ducard, Bruce prevents this plan from getting any further and heads back to his home. Back in his original surroundings, Bruce adopts the image of a bat to strike fear into the criminals and Batman Begins corrupt as the icon known as "Batman". But it doesn't stay quiet for long. Written by konstantinwe. I've just come back from a preview screening of Batman Batman Begins. I went in with low expectations, despite the excellence of Christopher Nolan's previous efforts. Talk about having your expectations confounded! This film grips like wet rope from the start. I won't give away any of the story; suffice to say it mixes and matches its sources freely, tossing in a dash of Frank Miller, a bit of Alan Moore and a pinch of Bob Kane to great effect. What's impressive is that despite the weight of the franchise, Nolan has managed to work so many of his trademarks into a mainstream movie. -

80S 90S Hand-Out

FILM 160 NOIR’S LEGACY 70s REVIVAL Hickey and Boggs (Robert Culp, 1972) The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975) Farewell My Lovely (Dick Richards, 1975) The Drowning Pool (Stuart Rosenberg, 1975) The Big Sleep (Michael Winner, 1978) RE- MAKES Remake Original Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) Postman Always Rings Twice (Bob Rafelson, 1981) Postman Always Rings Twice (Garnett, 1946) Breathless (Jim McBride, 1983) Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1959) Against All Odds (Taylor Hackford, 1984) Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947) The Morning After (Sidney Lumet, 1986) The Blue Gardenia (Fritz Lang, 1953) No Way Out (Roger Donaldson, 1987) The Big Clock (John Farrow, 1948) DOA (Morton & Jankel, 1988) DOA (Rudolf Maté, 1949) Narrow Margin (Peter Hyams, 1988) Narrow Margin (Richard Fleischer, 1951) Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991) Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1962) Night and the City (Irwin Winkler, 1992) Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) Kiss of Death (Barbet Schroeder 1995) Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947) The Underneath (Steven Soderbergh, 1995) Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949) The Limey (Steven Soderbergh, 1999) Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) The Deep End (McGehee & Siegel, 2001) Reckless Moment (Max Ophuls, 1946) The Good Thief (Neil Jordan, 2001) Bob le flambeur (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1955) NEO - NOIRS Blood Simple (Coen Brothers, 1984) LA Confidential (Curtis Hanson, 1997) Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986) Lost Highway (David -

Portraits of America DEMOCRACY on FILM

The Film Foundation’s Story of Movies Presents With support from AFSCME A PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOP ON FILM AND VISUAL LITERACY FOR CLASSROOM EDUCATORS ACROSS ALL DISCIPLINES, GRADES 5 – 12 Portraits of America DEMOCRACY ON FILM 2018 WORKSHOPS August 6 & 7 Breen Center for the Performing Arts, 2008 W 30th Street, Cleveland, OH 44113 August 14 & 15 Lightbox Film Center inside International House Philadelphia 3701 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 October 3 & 4 Detroit Institute of Arts, 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit, MI 48202 WHO & WHAT This FREE two-day seminar introduces educators to an interdisciplinary curriculum that challenges students to think contextually about the role of film as an expression of American democracy. SCREENING AND DISCUSSION ACTIVITIES FOCUS ON STRATEGIES TO: N Increase civic engagement by developing students’ critical viewing and thinking skills. N Give students the tools to understand the persuasive and universal language of moving images, a significant component ofvisual literacy. N Explore the social issues and diverse points of view represented in films produced in different historical periods. MORNING AND AFTERNOON WORKSHOPS FOCUS ON LEARNING HOW TO READ A FILM, PRINCIPLES OF CINEMA LITERACY, AND INTERPRETING FILM IN HISTORICAL/CULTURAL CONTEXTS. N Handout materials include screening activities and primary source documents to support and enhance students’ critical thinking skills. N Evening screenings showcase award-winning films, deemed historically and culturally significant by the Library of Congress National Film Registry. N Lunch is provided for registered participants. HOW & WHEN TO REGISTER CLASSROOM CAPACITY IS LIMITED, SO EARLY REGISTRATION IS ENCOURAGED. Continuing Education Credits may be supported by local school districts for this program. -

Film As Philosophy in Memento: Reforming Wartenberg's Imposition

!"#$%&'%()"#*'*+),%"-%!"#"$%&.% /01*2$"-3%4&250-60237'%8$+*'"5"*-%96:0;5"*- "#$%&#$'%()*+%*%,'-*,'%!"#$%&'(%)*"#+,+-*.%*+,%()'%/+01'&#%+2%34,5*45"6,% &'(%315%71"5"6",$%)*.'%/01234)',%*%$0++3+5%,'1*('%*4%(#%6)'()'$%-#&&'$-3*2% +*$$*(3.'%73-(3#+%732&4!%*$'%-*/*12'%#7%(+"'8%/)32#4#/)89%/'$)*/4%'.'+%#$353+*2% /)32#4#/)89%3+%()'3$%#6+%$35)(:%%;)34%,'1*('%1'5*+%63()%()'%*//'*$*+-'9%3+%<===9%#7% >$0-'%?044'22@4%A0*2373',28%+'5*(3.'%.'$,3-(%#+%()34%A0'4(3#+9%B;)'%C)32#4#/)3-*2% D3&3(4%#7%"32&9E<%*+,%F('/)'+%G02)*22@4%.'$8%3+720'+(3*2%/#43(3.'%.'$,3-(%*%8'*$% 2*('$9%3+%9'%!"#$:H%%F3+-'%()'+%+0&'$#04%*$(3-2'4%)*.'%1''+%,'.#(',%(#%()'%3440'9% 3+-20,3+5%()'%'+(3$'%I3+('$9%<==J%3440'%#7%:*4%/+01'&#%+2%34,5*45"6,%&'(%315% 71"5"6",$9K%*+,%*%4'(%#7%7#0$%*$(3-2'4%*//'*$3+5%3+%!"#$%&'(%)*"#+,+-*.%(6#%8'*$4% 2*('$:L%%"#0$%&#$'%1##M%2'+5()%($'*(&'+(4%#7%()'%(#/3-%)*.'%*24#%'&'$5',%()04%7*$N% O*+3'2%"$*&/(#+@4%!"#$+,+-*.%3+%<==J9J%;#&%I*$('+1'$5@4%:*"';"'8%+'%<6144'=% !"#$%&,%)*"#+,+-*.%3+%<==P9P%*%4'-#+,%',3(3#+9%5$'*(28%'Q/*+,',9%#7%G02)*22@4%9'% !"#$%3+%<==R9R%*+,%C*342'8%D3.3+54(#+@4%7"'4$&>%)*"#+,+-*.>%?418$&'=%9'%!"#$% &,%)*"#+,+-*.9%3+%<==S:S% T+'%3&/#$(*+(%-#+4($*3+(%#+%732&4%A0*23783+5%*4%403(*128%-*"#+,+-*"6&#%)*4% 1''+%F('/)'+%G02)*22@4%5$#0+,%$02'9%7$*&',%'*$28%3+%()'%,'1*('N%732&4%,#%+#(% -#0+(%*4%,#3+5%/)32#4#/)8%3+%()'3$%#6+%$35)(%37%()'8%&'$'28%2'+,%()'&4'2.'4%(#% /)32#4#/)3-*2%3+('$/$'(*(3#+%()$#05)%4@541'&#%*//23-*(3#+%#7%()'#$3'4:%%BF/'-373-% ()'#$'(3-*2%',373-'4%U#$353+*(3+5%'24'6)'$'9%3+%40-)%,#&*3+4%*4%/48-)#*+*28434% #$%/#23(3-*2%()'#$8V9E%4#&'(3&'4%($'*(%()'%(*$5'(%732&%B#+28%*4%*%-02(0$*2%/$#,0-(% -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Christopher Nolan's Insomnia & the Renewal

WHITE NIGHTS OF THE SoUL: CHRISTOPHER NoLAN's INSOMNIA & THE RENEWAL OF MORAL REFLECTION IN FILM1 J. L. A. Garcia "In this Light, how can you hide? You are not transparent enough while brightness breathes from every side. Look into yourself. here is your Friend, a single spark, yet Luminosity." -Pope john Paul II, "Shores of Silence" 2 "I said ... to Eve[ning], 'Be soon"' -Francis Thompson, "Hound of Heaven"3 "Insomnia is constituted by the consciousness that it will never finish-that is, that there is no longer any way of withdrawing from the vigilance to which one is held ... The present is welded to the past, is entirely the heritage of the past: it renews nothing. It is always the same present or the same past that endures ... "... this immortality from which one cannot escape ... a vigilance without recourse to sleep. That is to say, a vigilance without refuge in unconsciousness, without the possibility ofwithdrawing into sleep as into a private domain. " -Emmanuel Levinas, Time and the Other4 1 This article originally appeared in Logos 9:4 (Fall, 2006): 82-117 and is reprinted with permission. The author expresses his appreciation to Professors Laura Garcia and Thomas Hibbs, who helped him to look for deeper themes in movies and to think more seriously about them, although any mistakes are his own. j. Veith, V. Devendra, and Laura Garcia also assisted with citations and editing. 2 john Paul II, "Shores of Silence," in Collected Poems, translated by jerzy Peterkiewicz (New York: Random House, 1982), p. 7. 3 Francis Thompson, "The Hound of Heaven," in I Fled Him Down the Nights and Down the Days, with commentary and notes by john Quinn, S.j. -

A Look at Queer Stereotypes As Signifiers in DC Comics' the Joker

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-27-2018 Queering The loC wn Prince of Crime: A Look at Queer Stereotypes as Signifiers In DC Comics’ The Joker Zina Hutton [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006550 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Modern Literature Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Zina, "Queering The loC wn Prince of Crime: A Look at Queer Stereotypes as Signifiers In DC Comics’ The oJ ker" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3702. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3702 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida QUEERING THE CLOWN PRINCE OF CRIME: A LOOK AT QUEER STEREOTYPES AS SIGNIFIERS IN DC COMICS’ THE JOKER A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Zina Hutton 2018 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This thesis, written by Zina Hutton, and entitled Queering the Clown Prince of Crime: A Look at Queer Stereotypes as Signifiers in DC Comics’ The Joker, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. -

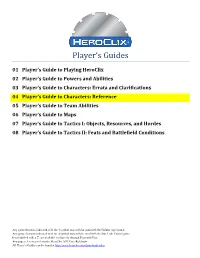

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................