Psychosocial Interventions in the Management of Schizophrenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Rather Life': Promoting Dada and Surrealism

Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction Very Short Introductions are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way in to a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been published in more than 25 languages worldwide. The series began in 1995, and now represents a wide variety of topics in history, philosophy, religion, science, and the humanities. Over the next few years it will grow to a library of around 200 volumes – a Very Short Introduction to everything from ancient Egypt and Indian philosophy to conceptual art and cosmology. Very Short Introductions available now: ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY Continental Philosophy Julia Annas Simon Critchley THE ANGLO-SAXON AGE COSMOLOGY Peter Coles John Blair CRYPTOGRAPHY ANIMAL RIGHTS David DeGrazia Fred Piper and Sean Murphy ARCHAEOLOGY Paul Bahn DADA AND SURREALISM ARCHITECTURE David Hopkins Andrew Ballantyne Darwin Jonathan Howard ARISTOTLE Jonathan Barnes Democracy Bernard Crick ART HISTORY Dana Arnold DESCARTES Tom Sorell ART THEORY Cynthia Freeland DRUGS Leslie Iversen THE HISTORY OF THE EARTH Martin Redfern ASTRONOMY Michael Hoskin EGYPTIAN MYTHOLOGY Atheism Julian Baggini Geraldine Pinch Augustine Henry Chadwick EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BARTHES Jonathan Culler BRITAIN Paul Langford THE BIBLE John Riches THE ELEMENTS Philip Ball BRITISH POLITICS EMOTION Dylan Evans Anthony Wright EMPIRE Stephen Howe Buddha Michael Carrithers ENGELS Terrell Carver BUDDHISM Damien Keown Ethics Simon Blackburn CAPITALISM James Fulcher The European Union THE CELTS Barry Cunliffe John Pinder CHOICE THEORY EVOLUTION Michael Allingham Brian and Deborah Charlesworth CHRISTIAN ART Beth Williamson FASCISM Kevin Passmore CLASSICS Mary Beard and THE FRENCH REVOLUTION John Henderson William Doyle CLAUSEWITZ Michael Howard Freud Anthony Storr THE COLD WAR Galileo Stillman Drake Robert McMahon Gandhi Bhikhu Parekh GLOBALIZATION PLATO Julia Annas Manfred Steger POLITICS Kenneth Minogue HEGEL Peter Singer POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY HEIDEGGER Michael Inwood David Miller HINDUISM Kim Knott POSTCOLONIALISM HISTORY John H. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES School of Humanities Doris Lessing and R. D. Laing: Madness and the Matter of the Body by Kerry Sara Myler Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 Errata i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy DORIS LESSING AND R. D. LAING: MADNESS AND THE MATTER OF THE BODY by Kerry Sara Myler With the publication of The Divided Self in 1960, R. D. Laing initiated the British ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement which was to challenge the hegemony of conventional medical and psychoanalytical models of madness during that decade and beyond. Anti-psychiatric thinking coincided with the beginning of the second wave of feminism and the two movements coalesced within a number of literary texts, most notably Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. -

Shaping Your Career in Research

Tuesday 6th June 2017 Queen Elizabeth Teaching and Learning Centre, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow, G51 4TF Shaping your career in research 09:30 Registration with tea and coffee 10:00 Welcome Professor Dame Anna Dominiczak DBE MD FRCP FAHA FRSE FMedSci, Regius Professor of Medicine, Vice Principal and Head College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow 10:10 The research landscape in Scotland Short talks on the outlook for clinical and non-clinical researchers • Professor Laura Machesky FRSE FMedSci, Professor of Cell Biology, CRUK Beatson Institute, University of Glasgow • Mr Damian Mole, Senior Clinical Lecturer, University of Edinburgh 11:00 Structured networking with tea and coffee Designed to facilitate quick introductions between attendees 11:45 My MedSciLife Hear more about ‘the person behind the science’, at different stages of a research career • Dr Margaret Cunningham, Chancellor’s Research Fellow, University of Strathclyde • Professor Iain McInnes FRCP FRSE FMedSci, Muirhead Professor of Medicine and Director of Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow • Professor Eve Johnstone CBE FRSE FMedSci, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Edinburgh 13:00 Lunch break with tours: Clinical Innovation Zone or Imaging Centre of Excellence 14:00 Pitching Ideas: Presentation Skills • Simon Cain, Westbourne Training & Consulting Can you drive home a message; to funders, peers or senior colleagues? In this interactive workshop you will learn simple tools and approaches to deliver a compelling argument. 15:30 Tea and coffee break 16:00 Research Culture: Visions of 2035 Imagine that you are a member of the UK research community in 2035: what does your ‘idealised’ research culture look like? How does it support a vibrant and diverse workforce? And how does it maintain and improve research excellence? Discuss these and other issues at this Royal Society run workshop. -

Hopsig News and Notes

HoPSIG News and Notes The newsletter of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ History of Psychiatry Special Interest Group Issue 5, Autumn 2017 HoPSIG & Archives News Editorial Welcome to all our readers, old and new! HoPSIG had a full house at our spring workshop and our session at the International Congress 2017 was also well attended (abstracts are available on our Meetings page). We intend to continue holding history workshop events three times a year, including at least one meeting outside London, and we are in discussion with the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London about making links with academic historians. This is our first issue published exclusively as an e-newsletter, the College’s preferred format for this sort of publication, and we are very grateful to Mark Turner, Digital Content Officer, for setting it up and putting this issue together. We are proud to say that HoPSIG has grown substantially, from a mere 120 people on our mailing list 2 years ago to the current figure of 1000. We are also appealing to trainees, and have three currently on the committee who are all involved in specific projects. As well as accruing interest within our own profession, HoPSIG has also had the pleasure of answering queries about the history of psychiatry from other fields and industries, including historians, radio and television producers, and a novelist. It is fair to say that we have also had a lot of fun, and we hope that you enjoy reading this issue as much as we have enjoyed reading all of your contributions and editing it! Paul Lomax is stepping down from the HoPSIG committee, so we have a vacancy for another trainee. -

Fellows Opted out of Mentoring Scheme - As of 18Th July 2016

Fellows opted out of mentoring scheme - as of 18th July 2016 Name Position / Job Title Employer Name Professor Christopher Abell FRS Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Professor of FMedSci Biological Chemistry University of Cambridge Pro-Vice Chancellor and Head of College of Medical and Dental Sciences and Professor of Professor David Adams FMedSci Hepatology University of Birmingham Professor Desmond Archer OBE Professor Emeritus of FMedSci Ophthalmology Queen's University Belfast Sir Derek Barton Professor of Synthesis and Glaxo Professor of Professor Anthony Barrett FRS Organic Chemistry, Head of Synthesis FMedSci Section Imperial College London Professor of Vascular Professor Jill Belch OBE FMedSci Medicine/Consultant Physician University of Dundee Head of Division of Diabetes Sir Stephen Bloom FRS FMedSci Endocrinology and Metabolism Imperial College London Professor Emeritus and Director of Sir Tom Blundell FRS FMedSci Research University of Cambridge International Prevention Professor Peter Boyle FRSE FMedSci President Research Institute Professor George Brownlee FRS Emeritus Professor of Chemical FMedSci Pathology University of Oxford Sir Arnold Burgen FRS FMedSci Barts and The London, Queen Mary's School of Professor Mark Caulfield FMedSci Co-Director Medicine and Dentistry Honorary Fellow and Past Chairman of UCL Partners Academic Health Sir Cyril Chantler FMedSci Science Partnership Professor of Surgery, Paul Hamlyn Lord Ara Darzi PC KBE FRS Chair of Surgery; Director, Institute HonFREng FMedSci of Global Health Innovation Imperial College -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Book Reviews Michael H. Ebert, M.D., Editor Managing© Care, Copyright Not Dollars: 2001 Physicianssion Postgraduate making, academic integrity, Press, and humanistic Inc. treatment and The Continuum of Mental Health Services the modeling of these values in our treatment of our residents. edited by Robert K. Schreter, M.D.; Steven S. Scharfstein, Section IV considers public policy issues, including the role M.D., M.P.A.; and Carol A. Schreter, M.S.W., Ph.D. of the public sector and of family and consumer advocacy. Pub- Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Press, 1997, lic health considerations, state and local controls, guiding prin- 383 pages, $55.00. ciples and system components, and particular issues related to homelessness, children, and legislative mandates are reviewed, Managing Care, Not Dollars calls us to shift our perspective as are the roles of families and communities, self-help pro- on managed care from fear to embracement, from cost contain- grams, recreation, education, and employment. ment to the coherent delivery of state-of-the-art services. Clearly and cogently presented, Managing Care, Not Dollars “The concept of the continuum of care with multiple compo- is a “must read” for consumers, clinicians, and managers of men- nents is not a new idea,” we are reminded in the foreword: “It tal health services on the brink of the new millennium. “Overall, derives from community mental health principles and ideas de- this book is a how-to manual, a guide to setting up and using the veloped in the 1960s as a means to provideOne continuity personal of care, copy a mayemerging be printed continuum of care,” we are told in the introduction. -

Spring 2014 Message from Our President—Building a Cathedral James P

The Westchester Psychiatrist A quarterly publication of the Psychiatric Society of Westchester County Spring 2014 Message From Our President—Building A Cathedral James P. Kelleher, M.D. 2013-2014 We are grateful to the Bronx DB for wel- Executive Council coming us this year and for providing a James P. Kelleher, MD memorable evening. The speakers, Dr. Su- President san Whitley, Director of Chemical Depend- ency Services, Kings County Hospital Center, Carlo Bayrakdarian, MD President-Elect and Sandra Turner, Program Manager, Pal- liative Syringe Program, St. Ann’s Corner of Barbara Goldblum, MD Harm Reduction, gave a very important Secretary presentation about saving lives through ear- Richard McCarthy, MD ly intervention in heroin overdose. Some of Treasurer their data indicated that by providing sup- Fady Hajal, MD plies of naloxone and training to community Past-President members, a life could be saved for about (2012-2013) There is a story of three men working un- $50. I admire their work. Anthony Stern, MD derground. When asked what they’re do- Program Coordinator ing, the first two say they’re digging a hole. The theme of this year’s APA meeting, held in New York, was Changing the Practice and Karl Kessler, MD The third answers, “I’m building a cathe- Program Coordinator-Elect dral.” I think that metaphor represents the Perception of Psychiatry. I learned a great attitude of the Westchester District Branch deal from the presentations of Drs. Matthew Susan Stabinsky, MD State (about developments in psychiatric Legislative Representative during the last year and I hope it has shone through in our work. -

The History of the Australasian Society for Psychiatric Research 1978-2004

The History of the Australasian Society for Psychiatric Research 1978-2004 THE APPENDICES Appendices for the University of Western Australia History of ASPR undergraduate student practicum project Produced by Victoria Tait and based on her interviews and archival research Supervisor: Vera Morgan Date 07 November 2006 CONTENTS Foundation Members......................................................................... 2 Past Presidents and Committee Members 1978-2004...................... 4 Summary of the annual scientific meeting – year, location, theme, plenary speakers 1979-2004........................................................... 10 Summaries of the Annual General Meetings – Issues Covered 1978-2004 ....................................................................................... 16 Original aims, circa 1984................................................................. 29 Australian Society for Psychiatric Research – Original constitution and Rules 1981 ............................................................................... 31 Australasian Society for Psychiatric Research - Revised Constitution and Rules (pre-2004 constitution) ............................... 34 Foundation Members Mary Abrahams Professor Brian Davies University of Queensland Royal Melbourne Hospital Dr Lois Achimovich Dr Alys Donnan Darlington, WA Monash University Alfred Hospital, VIC Professor K. S. Adam Christchurch Hospital, NZ Dr L. R. H. Drew Commonwealth Department of Dr J. G. Andrews Health ACT University of NSW H. D. Eastwell Dr J. Antonio -

Diaspora: a Very Short Introduction for Rosanna, Michelino, and Owen Acknowledgments

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form, and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kenny, Kevin, 1960– Diaspora : a very short introduction / Kevin Kenny. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-19-985858-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Human beings—Migrations. 2. Emigration and immigration. 3. Transnationalism. 4. Culture and globalization. 5. Human geography. I. Title. GN370.K46 2013 304.8—dc23 2012043546 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in Great Britain by Ashford Colour Press Ltd., Gosport, Hants. -

Understanding Schizophrenia / Older and Wiser?

E D iT understanding schizophrenia / older and wiser? / new student writing The University of Edinburgh Magazine volume two issue two summer 2000 E D iTcontents The University of Edinburgh Magazine volume two issue two summer 2000 14 08 26 50 18 22 COVER STORIES 08 MISTAKEN IDENTITY - a study of schizophrenia. Jennifer Trueland. 14 DOWNSTREAM - a short story. Jennifer Hadfield. 26 GROWING OLD: SAGACIOUS OR SENILE? - the way we were. Ian Deary. publisher Communications & Public Affairs, FEATURES The University of Edinburgh Centre, 12 STARTER FOR TEN - Allan Little has the answers. 7-11 Nicolson Street, Edinburgh EH8 9BE A MOMENTARY VIEW - a year in the life in pictures. 18 editor Anne McKelvie 24 LETTER FROM EDINBURGH - a giant leap for womankind. Edith Pechey. assistant editors 50 A LITTLE LOCAL DELICACY - Polynesian style. John Atherton. David Eccles, Richard Mellis design The University of Edinburgh 2000 Neil Dalgleish for Visual Resources, REGULARS © The University of Edinburgh photography 04 EditEd - on the University news front. No part of this publication may be Tricia Malley, Ross Gillespie, 22 ExhibitEd - the art of the University. reproduced in any form Visual Resources, without the prior written The University of Edinburgh 31 OMNIANA - The Peabody of the East. consent of the publishers. Edit is advertising sales agent printed on environment- LETTERS - there’s a quaich to be won. Mediaworks 32 friendly low chlorine content paper. Edit, The 58 Southwold Road 38 InformEd - for Edinburgh graduates world wide. University of Edinburgh Paisley PA1 3AL Magazine, is published Tel/Fax: 0141 882 1768 twice a year. The views expressed in its columns are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent those of the University. -

UNIVERSITIES and COLLEGES Analysis Using Electrochemical Sensors

576 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 23 FEBRUARY 1980 Royal College of Radiologists, British Institute of Radiology, and Royal Society of Medicine Radiology Section-Joint radiological meeting, 28-29 BMA NOTICES March, Southampton. Details from the meetings Instructions to authors secretary of the college, 38 Portland Place, London WIN 3DG. Central Meetings "Medical aspects of adoption and long-term The following are the minimum require- fostering"-Seminar, 22-24 April, Manchester. Details FEBRUARY ments for manuscripts submitted for from the conference organiser, Association of British 26 Tues Scottish Joint Consultants Committee (7 Adoption and Fostering Agencies, 4 Southampton Row, Drumsheugh Gardens, Edinburgh EH3 publication. London WC1B 4AA. (Tel 01-242 8951.) Closing date 7QP), 10.15 am. A stamped addressed envelope or an for applications 17 March. 27 Wed Council Executive, 10.30 am. international reply coupon must accompany Atkinson Morley's Hospital Neurological Depart- ment-Day course on "Disorders of speech," 10 May, MARCH the manuscript if acknowledgment of its London. Details from the neurological office of the 5 Wed Central Ethical Committee, 10 am. receipt is desired. hospital, Copse Hill, Wimbledon, London SW20. 5 Wed Finance and General Purposes Committee, (Tel 01-946 7711.) 10 am. 6 Thurs General Purposes Subcommittee (GMSC), (1) Typing should be on one side of the Marie Curie Memorial Foundation-Symposium 10.30 am. "Cancer-questions and answers," 20 May, London. 10 Mon Medical Academic Staff Committee, 10 am. paper, with double or triple spacing Details from the foundation, 124 Sloane Street, London 12 Wed Negotiating Subconmmittee (CCHMS), 10 between the lines and 5-cm margins at the SW1X 9BP. -

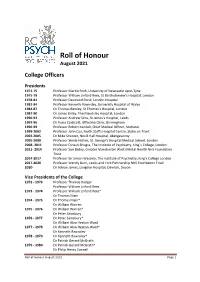

Roll of Honour August 2021

Roll of Honour August 2021 College Officers Presidents 1971-75 Professor Martin Roth, University of Newcastle upon Tyne 1975-78 Professor William Linford Rees, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London 1978-81 Professor Desmond Pond, London Hospital 1981-84 Professor Kenneth Rawnsley, University Hospital of Wales 1984-87 Dr Thomas Bewley, St Thomas’s Hospital, London 1987-90 Dr James Birley, The Maudsley Hospital, London 1990-93 Professor Andrew Sims, St James’s Hospital, Leeds 1993-96 Dr Fiona Caldicott, Uffculme Clinic, Birmingham 1996-99 Professor Robert Kendell, Chief Medical Officer, Scotland 1999-2002 Professor John Cox, North Staffs Hospital Centre, Stoke on Trent 2002-2005 Dr Mike Shooter, Nevill Hall Hospital, Abergavenny 2005-2008 Professor Sheila Hollins, St. George’s Hospital Medical School, London 2008- 2011 Professor Dinesh Bhugra, The Institute of Psychiatry, King`s College, London 2011- 2014 Professor Sue Bailey, Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust 2014-2017 Professor Sir Simon Wessely, The Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London 2017-2020 Professor Wendy Burn, Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust 2020- Dr Adrian James, Langdon Hospital, Dawlish, Devon Vice Presidents of the College 1972 - 1973 Professor Thomas Rodger Professor William Linford Rees 1973 - 1974 Professor William Linford Rees* Dr Thomas Main 1974 - 1975 Dr Thomas Main* Dr William Warren 1975 - 1976 Dr William Warren* Dr Peter Sainsbury 1976 - 1977 Dr Peter Sainsbury* Dr William Alan Heaton-Ward 1977 - 1978 Dr William Alan