I Love Sacred .. Harp Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter November 2007

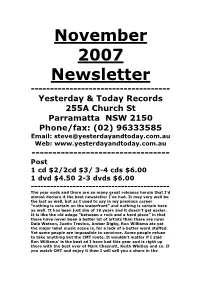

November 2007 Newsletter ------------------------------------ Yesterday & Today Records 255A Church St Parramatta NSW 2150 Phone/fax: (02) 96333585 Email: [email protected] Web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au --------------------------------- Post 1 cd $2/2cd $3/ 3-4 cds $6.00 1 dvd $4.50 2-3 dvds $6.00 ------------------------------------------- The year ends and there are so many great releases herein that I’d almost declare it the best newsletter I’ve had. It may very well be the last as well, but as I used to say in my previous career “nothing is certain on the waterfront” and nothing is certain here as well. It has been just shy of 19 years and it doesn’t get easier. It is like the old adage “between a rock and a hard place” in that there have never been a better lot of artists than there are now: Dale Watson, Justin Trevino, Amber Digby, Ron Williams etc yet the major label music scene is, for a lack of a better word stuffed. Yet some people are impossible to convince. Some people refuse to take anything but the CMT route. It wouldn’t matter if I said Ron Williams’ is the best cd I have had this year and is right up there with the best ever of Mark Chesnutt, Keith Whitley and co. If you watch CMT and enjoy it then I will sell you a share in the Sydney Harbour Bridge. If you watch it and question its merit we have the answers for you. Please read on. ----------------------------------- Ron Williams – “Texas Style” $32 If anything beats this as album of the year I will be very surprised. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 Cds for $10 Each!

THOMAS FRASER I #79/168 AUGUST 2003 REVIEWS rQr> rÿ p rQ n œ œ œ œ (or not) Nancy Apple Big AI Downing Wayne Hancock Howard Kalish The 100 Greatest Songs Of REAL Country Music JOHN THE REVEALATOR FREEFORM AMERICAN ROOTS #48 ROOTS BIRTHS & DEATHS s_________________________________________________________ / TMRU BESTSELLER!!! SCRAPPY JUD NEWCOMB'S "TURBINADO ri TEXAS ROUND-UP YOUR INDEPENDENT TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 CDs for $10 each! #1 TMRU BESTSELLERS!!! ■ 1 hr F .ilia C s TUP81NA0Q First solo release by the acclaimed Austin guitarist and member of ’90s. roots favorites Loose Diamonds. Scrappy Jud has performed and/or recorded with artists like the ' Resentments [w/Stephen Bruton and Jon Dee Graham), Ian McLagah, Dan Stuart, Toni Price, Bob • Schneider and Beaver Nelson. • "Wall delivers one of the best start-to-finish collections of outlaw country since Wayton Jennings' H o n k y T o n k H e r o e s " -Texas Music Magazine ■‘Super Heroes m akes Nelson's" d e b u t, T h e Last Hurrah’àhd .foltowr-up, üflfe'8ra!ftèr>'critieat "Chris Wall is Dyian in a cowboy hat and muddy successes both - tookjike.^ O boots, except that he sings better." -Twangzirtc ;w o tk s o f a m e re m o rta l.’ ^ - -Austin Chronlch : LEGENDS o»tw SUPER HEROES wvyw.chriswatlmusic.com THE NEW ALBUM FROM AUSTIN'S PREMIER COUNTRY BAND an neu mu - w™.mm GARY CLAXTON • acoustic fhytftm , »orals KEVIN SMITH - acoustic bass, vocals TON LEWIS - drums and cymbals sud Spedai td truth of Oerrifi Stout s debut CD is ContinentaUVE i! so much. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

A Selective Study of Negro Worksongs in the United States Margaret E

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1976 A Selective Study of Negro Worksongs in the United States Margaret E. Hilton Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Music at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hilton, Margaret E., "A Selective Study of Negro Worksongs in the United States" (1976). Masters Theses. 3429. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3429 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SELECTIVE STUDY OF NEGRO WORKSONGS IN THE UNITED STATES (TITLE) BY MARGARET E. HILTON THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENlS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1976 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE 5'/t.. g�,.i� 1 ADVISER �t9/t '"(' •err 8'4r: DEPARTMENT HEAD I PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. ' The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holding s . Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a. -

Spanish Fort Town Center Cell: 251-591-3168 Cell: 251-975-8222 20000 Bass Pro Drive, Spanish Fort, AL [email protected] [email protected]

Angela McArthur Jeff Barnes, CCIM Direct: 251-375-2481 Direct: 251-375-2496 Spanish Fort Town Center Cell: 251-591-3168 Cell: 251-975-8222 20000 Bass Pro Drive, Spanish Fort, AL [email protected] [email protected] Overview Site Plan Lease Plan Aerial Photos Signage Demos 447,748 SF Mixed Use Development For Lease on 230 Acres Bass Pro Anchored Property Description Prominently positioned along Interstate 10 in Spanish Fort, Alabama, Spanish Fort Town Center is a signature mixed-use development serving the Mobile / Pensacola MSA. Anchored by Bass Pro Shop, a regional destination tenant that draws customers from a 100 mile radius, Spanish Fort Town Center is poised to take advantage of being centrally located in the fastest growing county in Alabama. Attributes of the property include great exposure and access at the northeast corner of Interstate 10 and US Highway 98, views of Mobile Bay, established anchor tenants, direct proximity to a maturing trade area, restaurants, and over 1 million square feet of retail shopping. This 230 acre development includes retail space, restaurant sites, hotels, a multi-family component, and land for future commercial development. Available Traffic Counts ( ADT 2015) • 1,200 SF and Up • Highway 98: 33,650 • Interstate 10: 60,670 • Outparcels from .94 to 7.09 Acres with Built to Suit Opportunities Parking • 12:1 Parking Ratio Zoning • B-2 Property Highlights • Interstate Frontage • Easy Access • Prominent Sign Bands • High Traffic Counts Developed and Managed by: • Competitive Rates The foregoing is solely for information purposes and is subject to change without notice. Stirling Properties makes no representations or warranties regarding the properties or information herein including but not stirlingproperties.com limited to any and all images pertaining to these properties. -

Benjamin Britten's "Evening Primrose" 27 • Chester Alwes Analyzes Britten's Manipulation of Poetic Text for Compositional Purposes

August 2004 Contents Vol 45 ·no.I Articles .. Shout All Over God's Heaven 9 • Thomas Lloyd discusses how the African-American spiritual has maintained its integrity in the face of major social and musical challenges. Words and Music: Benjamin Britten's "Evening Primrose" 27 • Chester Alwes analyzes Britten's manipulation of poetic text for compositional purposes. An Interview with Dale Warland 35 • Diana Leland talks to Dale Warland about his career highlights, his legacy, and his plans after he leaves the choir that bears his now famous name. Columns Rehearsal Break: Acoustic Issues and the Choral Singer 45 • Margaret Olson addresses how individual choral singers should adjudicate their vocal output during rehearsal. Repertoire and Standards 53 • Nancy Cox gives tips for making a good audition tape. • Vijay Singh shares ways to personalize your jazz performance. Hallelujah! The Best First Church Choir Rehearsal 63 • Tim Sharp explains how to create a good first impression with a new church choir. Compact Disc Reviews 77 • David Castleberry Book Reviews 81 • Stephen Town Choral Reviews 91 • Lyn Schenbeck The Choral Journal is the official publication of The American Choral Directors Association (ACDA). ACDA is a nonprofit professional organization of choral directors In This Issue from schools, colleges, and universities; community, church, and professional choral ensembles; and industry and institutional organizations. Choral Journal circulation: 21,000. Annual dues (includes subscription to the Choral Joumety: Active $65, Industry From the Executive Director 4 $100, Institutional $75, Retired $25, and Student $20. One-year membership begins on date of dues acceptance. Library annual subscription rates: U.S. -

GUIDE to MOBILE a Great Place to Live, Play Or Grow a Business

GUIDE TO MOBILE A great place to live, play or grow a business 1 Every day thousands of men and women come together to bring you the wonder © 2016 Alabama Power Company that is electricity, affordably and reliably, and with a belief that, in the right hands, this energy can do a whole lot more than make the lights come on. It can make an entire state shine. 2 P2 Alabama_BT Prototype_.indd 1 10/7/16 4:30 PM 2017 guide to mobile Mobile is a great place to live, play, raise a family and grow a business. Founded in 1702, this port city is one of America’s oldest. Known for its Southern hospitality, rich traditions and an enthusiastic spirit of fun and celebration, Mobile offers an unmatched quality of life. Our streets are lined with massive live oaks, colorful azaleas and historic neighborhoods. A vibrant downtown and quality healthcare and education are just some of the things that make our picturesque city great. Located at the mouth of the Mobile River at Mobile Bay, leading to the Gulf of Mexico, Mobile is only 30 minutes from the sandy white beaches of Dauphin Island, yet the mountains of northern Alabama are only a few hours away. Our diverse city offers an endless array of fun and enriching activities – from the Alabama Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo to freshwater fishing, baseball to football, museums to the modern IMAX Dome Theater, tee time on the course to tea time at a historic plantation home, world-renowned Bellingrath Gardens to the Battleship USS ALABAMA, Dauphin Island Sailboat Regatta to greyhound racing, Mardi Gras to the Christmas parade of boats along Dog River. -

The Lubbock Texas Quartet and Odis 'Pop' Echols

24 TheThe LubbockLubbock TexasTexas QuartetQuartet andand OdisOdis “Pop”“Pop” Echols:Echols: Promoting Southern Gospel Music on the High Plains of Texas Curtis L. Peoples The Original Stamps Quartet: Palmer Wheeler, Roy Wheeler, Dwight Brock, Odis Echols, and Frank Stamps. Courtesy of Crossroads of Music Archive, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, Echols Family Collection, A Diverse forms of religious music have always been important to the cultural fabric of the Lone Star State. In both black and white communities, gospel music has been an influential genre in which many musicians received some of their earliest musical training. Likewise, many Texans have played a significant role in shaping the national and international gospel music scenes. Despite the importance of gospel music in Texas, little scholarly attention has been devoted to this popular genre. Through the years, gospel has seen stylistic changes and the 25 development of subgenres. This article focuses on the subgenre of Southern gospel music, also commonly known as quartet music. While it is primarily an Anglo style of music, Southern gospel influences are multicultural. Southern gospel is performed over a wide geographic area, especially in the American South and Southwest, although this study looks specifically at developments in Northwest Texas during the early twentieth century. Organized efforts to promote Southern gospel began in 1910 when James D. Vaughn established a traveling quartet to help sell his songbooks.1 The songbooks were written with shape-notes, part of a religious singing method based on symbols rather than traditional musical notation. In addition to performing, gospel quartets often taught music in peripatetic singing schools using the shape-note method. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent.