Chapter 18 Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 25, 2010 (Pages 5442-5550)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 40 (2010) Repository 9-25-2010 September 25, 2010 (Pages 5442-5550) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2010 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "September 25, 2010 (Pages 5442-5550)" (2010). Volume 40 (2010). 39. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2010/39 This September is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 40 (2010) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 40 Number 39 Saturday, September 25, 2010 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 5443—5550 Agencies in this issue The Courts Bureau of Professional and Occupational Affairs Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Labor and Industry Department of Public Welfare Department of Revenue Department of Transportation Environmental Quality Board Executive Board Fish and Boat Commission Game Commission Health Care Cost Containment Council Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission State Board of Nursing State Conservation Commission State Ethics Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporters (Master Transmittal Sheets): No. 430, September 2010 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- BULLETIN reau, 641 Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, (ISSN 0162-2137) under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publi- cation and effectiveness of Commonwealth Documents). -

2021 PA Fishing Summary

2021 Pennsylvania Fishing Summary/ Boating Handbook MENTORED YOUTH TROUT DAY March 27 (statewide) FISH-FOR-FREE DAYS May 30 and July 4 Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 TROUT OPENER April 3 Statewide Pennsylvania Fishing Summary/Boating Handbookwww.fishandboat.com www.fishandboat.com 1 2 www.fishandboat.com Pennsylvania Fishing Summary/Boating Handbook PFBC LOCATIONS/TABLE OF CONTENTS For More Information: The mission of the Pennsylvania State Headquarters Centre Region Office Fishing Licenses: Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 is to protect, conserve, and enhance P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Boat Registration/Titling: the Commonwealth’s aquatic Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Lobby Phone: (814) 359-5124 resources, and provide fishing and Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Fisheries Admin. Phone: boating opportunities. Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. (814) 359-5110 Publications: Monday through Friday Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Phone: (717) 705-7835 Monday through Friday Contents Boating Safety Regulations by Location Education Courses The PFBC Website: (All fish species) Phone: (888) 723-4741 www.fishandboat.com www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia Inland Waters............................................ 10 Pymatuning Reservoir............................... 12 Region Offices: Law Enforcement/Education Conowingo Reservoir................................ 12 Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating Delaware River and Estuary...................... -

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

To Cumberland County Sites

A NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY OF CUMBERLAND COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Update – 2005 A NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY OF CUMBERLAND COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Update – 2005 Prepared by: The Pennsylvania Science Office The Nature Conservancy 208 Airport Drive Middletown, Pennsylvania 17057 Submitted to: The Tri-County Regional Planning Commission Dauphin County Veterans Memorial Office Building 112 Market Street, Seventh Floor Harrisburg, PA 17101-2015 (717-234-2639) This project was financed in part by a grant from the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund, under the administration of the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation and a Community Development Block Grant, under the administration of the PA Department of Community and Economic development, Office of Community Development and Housing. Subwatersheds of Cumberland County Pictures\Subwatesheds.doc Cumberland Streams (order) 0 - 1 1 - 3 3 - 7 Cumberland County Cumberland_subsheds.shp "BEAR HOLLOW" "BETTEM HOLLOW" "DEAD WOMAN HOLLOW" "HAIRY SPRINGS HOLLOW" "IRISHTOWN GAP HOLLOW" "KELLARS GAP HOLLOW" "KINGS GAP HOLLOW" "PEACH ORCHARD HOLLOW" "RESERVOIR HOLLOW" "STATE ROAD HOLLOW" "STHROMES HOLLOW" "WASP HOLLOW" "WATERY HOLLOW" ALEXANDERS SPRING CREEK BACK CREEK BERMUDIAN CREEK BIG SPRING CREEK BIRCH RUN BLOSER CREEK BORE MILL RUN BRANDY RUN BULLS HEAD BRANCH BURD RUN CEDAR RUN CENTER CREEK Forested buffers help protect streams and CLIPPINGERS RUN COLD SPRING RUN creeks from non-point sources of CONODOGUINET CREEK DOGWOOD RUN pollution and help -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

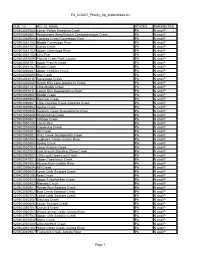

PA COAST Priority Ag Watersheds.Xls

PA_COAST_Priority_Ag_Watersheds.xls HUC_12 HU_12_NAME STATES PARAMETER 020503050505 Lower Yellow Breeches Creek PA N and P 020700040601 Headwaters West Branch Conococheague Creek PA N and P 020503060904 Cocalico Creek-Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061104 Middle Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061701 Conoy Creek PA N and P 020503061103 Upper Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061105 Lititz Run PA N and P 020503051009 Fishing Creek-York County PA N and P 020402030701 Upper French Creek PA N and P 020503061102 Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503060801 Upper Chickies Creek PA N and P 020402030608 Hay Creek PA N and P 020503051010 Conewago Creek PA N and P 020402030606 Green Hills Lake-Allegheny Creek PA N and P 020503061101 Little Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503051011 Laurel Run-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020503060902 Middle Creek PA N and P 020503060903 Hammer Creek PA N and P 020503060901 Little Cocalico Creek-Cocalico Creek PA N and P 020503050904 Spring Creek PA N and P 020503050906 Swatara Creek-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020402030605 Wyomissing Creek PA N and P 020503050801 Killinger Creek PA N and P 020503050105 Laurel Run PA N and P 020402030408 Cacoosing Creek PA N and P 020402030401 Mill Creek PA N and P 020503050802 Snitz Creek-Quittapahilla Creek PA N and P 020503040404 Aughwick Creek-Juniata River PA N and P 020402030406 Spring Creek PA N and P 020402030702 Lower French Creek PA N and P 020503020703 East Branch Standing Stone Creek PA N and P 020503040802 Little Lost Creek-Lost Creek PA N and P 020503041001 Upper Cocolamus Creek -

June 4, 2011 (Pages 2829-2922)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 41 (2011) Repository 6-4-2011 June 4, 2011 (Pages 2829-2922) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2011 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "June 4, 2011 (Pages 2829-2922)" (2011). Volume 41 (2011). 23. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2011/23 This June is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 41 (2011) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 41 Number 23 Saturday, June 4, 2011 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 2829—2922 Agencies in this issue The Courts Bureau of Professional and Occupational Affairs Department of Banking Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Public Welfare Environmental Hearing Board Fish and Boat Commission Game Commission Independent Regulatory Review Commission Patient Safety Authority Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission State Board of Chiropractic State Conservation Commission State Registration Board for Professional Engineers, Land Surveyors and Geologists Susquehanna River Basin Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporters (Master Transmittal Sheets): No. 439, June 2011 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- BULLETIN reau, 641 Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, (ISSN 0162-2137) under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publi- cation and effectiveness of Commonwealth Documents). -

State Water Plan Subbasin 07B Conodoguinet Creek Watershed Franklin and Cumberland Counties

Updated 5/2004 Watershed Restoration Action Strategy (WRAS) State Water Plan Subbasin 07B Conodoguinet Creek Watershed Franklin and Cumberland Counties Introduction The 524-square mile Conodoguinet Creek watershed drains the northern two thirds of Cumberland County and the upper third of Franklin County and flows into the Susquehanna River at West Fairview across from the city of Harrisburg. The subbasin consists of 682 relatively small streams, many of which are unnamed tributaries. The subbasin contains 838 stream miles. The largest tributary watersheds are Middle Spring Creek with a 47.7 square mile drainage basin and Muddy Run at 42.1 square miles. All the other tributaries have drainage areas less than 25 square miles. The subbasin is included in HUC Area 2050305, Lower Susquehanna River, Swatara Creek, a Category I, FY99/2000 Priority watershed in the Unified Watershed Assessment. Geology/Soils The majority of the subbasin is in the Ridge and Valley Ecoregion. Blue (North) Mountain forms the northern border in both counties and South Mountain forms the southern border in Franklin County and southwestern Cumberland County. The limestone valley in the lower half, the shale ridges in the northern half of Cumberland County, and the long, narrow ridges and valleys in the Franklin County portion, result in an unusual drainage pattern and watershed outline. The upper third of the Conodoguinet Creek watershed is constricted between Blue Mountain and Kittatinny Mountain in a narrow, forested, low gradient valley, called Horse Valley, which resembles a tail. Small, high gradient tributaries originate on the ridges in the tail portion. Farther east, Blue Mountain is twisted into a large, steep fold called Doubling Gap and a smaller fold just east called McClures Gap. -

Class a Wild Trout Waters Created: August 16, 2021 Definition of Class

Class A Wild Trout Waters Created: August 16, 2021 Definition of Class A Waters: Streams that support a population of naturally produced trout of sufficient size and abundance to support a long-term and rewarding sport fishery. Management: Natural reproduction, wild populations with no stocking. Definition of Ownership: Percent Public Ownership: the percent of stream section that is within publicly owned land is listed in this column, publicly owned land consists of state game lands, state forest, state parks, etc. Important Note to Anglers: Many waters in Pennsylvania are on private property, the listing or mapping of waters by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission DOES NOT guarantee public access. Always obtain permission to fish on private property. Percent Lower Limit Lower Limit Length Public County Water Section Fishery Section Limits Latitude Longitude (miles) Ownership Adams Carbaugh Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Carbaugh Reservoir pool 39.871810 -77.451700 1.50 100 Adams East Branch Antietam Creek 1 Brook Headwaters to Waynesboro Reservoir inlet 39.818420 -77.456300 2.40 100 Adams-Franklin Hayes Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 31 Bedford Bear Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Mouth 40.207730 -78.317500 0.77 100 Bedford Ott Town Run 1 Brown Headwaters to Mouth 39.978611 -78.440833 0.60 0 Bedford Potter Creek 2 Brown T 609 bridge to Mouth 40.189160 -78.375700 3.30 0 Bedford Three Springs Run 2 Brown Rt 869 bridge at New Enterprise to Mouth 40.171320 -78.377000 2.00 0 Bedford UNT To Shobers Run (RM 6.50) 2 Brown -

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - November 2018

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - November 2018 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 7.91 Armstrong Birch Run Allegheny River Headwaters dnst to mouth 41.033300 -79.619414 1.10 Armstrong Bullock Run North Fork Pine Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.879723 -79.441391 1.81 Armstrong Cornplanter Run Buffalo Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.754444 -79.671944 1.76 Armstrong Cove Run Sugar Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.987652 -79.634421 2.59 Armstrong Crooked Creek Allegheny River Headwaters to conf Pine Rn 40.722221 -79.102501 8.18 Armstrong Foundry Run Mahoning Creek Lake Headwaters -

Fishing Summary Fishing Summary

2019PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws MENTORED YOUTH TROUT DAYS March 23 (regional) and April 6 (statewide) WHAT’S NEW FOR 2019 l Changes to Susquehanna and Juniata Bass Regulations–page 11 www.PaBestFishing.com l Addition and Removal to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 PFBC social media and mobile app: l Addition to Catch and Release Lakes Waters–page 15 www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia l Addition to Misc. Special Regulations–page 16 Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 30 AND April 13 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Go Fishin’ in Franklin County Chambersburg Trout Derby May 4-5, 2019 Area’s #1 Trout Derby ExploreFranklinCountyPA.com Facebook.com/FCVBen | Twitter.com/FCVB 866-646-8060 | 717-552-2977 2 www.fishandboat.com 2019 Pennsylvania Fishing Summary Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the PFBC LOCATIONS/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. FOR MORE INFORMATION: THANK YOU STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: for the purchase 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: Phone: (866) 262-8734 license! Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish & Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: EDUCATION COURSES Commonwealth’s aquatic resources, www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co.