Middle Conodoguinet Creek Watershed Rivers Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Section 106 Annual Report - 2019

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Section 106 Annual Report - 2019 Prepared by: Cultural Resources Unit, Environmental Policy and Development Section, Bureau of Project Delivery, Highway Delivery Division, Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Date: April 07, 2020 For the: Federal Highway Administration, Pennsylvania Division Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Officer Advisory Council on Historic Preservation Penn Street Bridge after rehabilitation, Reading, Pennsylvania Table of Contents A. Staffing Changes ................................................................................................... 7 B. Consultant Support ................................................................................................ 7 Appendix A: Exempted Projects List Appendix B: 106 Project Findings List Section 106 PA Annual Report for 2018 i Introduction The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) has been delegated certain responsibilities for ensuring compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (Section 106) on federally funded highway projects. This delegation authority comes from a signed Programmatic Agreement [signed in 2010 and amended in 2017] between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), and PennDOT. Stipulation X.D of the amended Programmatic Agreement (PA) requires PennDOT to prepare an annual report on activities carried out under the PA and provide it to -

Jjjn'iwi'li Jmliipii Ill ^ANGLER

JJJn'IWi'li jMlIipii ill ^ANGLER/ Ran a Looks A Bulltrog SEPTEMBER 1936 7 OFFICIAL STATE September, 1936 PUBLICATION ^ANGLER Vol.5 No. 9 C'^IP-^ '" . : - ==«rs> PUBLISHED MONTHLY COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA by the BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS PENNSYLVANIA BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS HI Five cents a copy — 50 cents a year OLIVER M. DEIBLER Commissioner of Fisheries C. R. BULLER 1 1 f Chief Fish Culturist, Bellefonte ALEX P. SWEIGART, Editor 111 South Office Bldg., Harrisburg, Pa. MEMBERS OF BOARD OLIVER M. DEIBLER, Chairman Greensburg iii MILTON L. PEEK Devon NOTE CHARLES A. FRENCH Subscriptions to the PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER Elwood City should be addressed to the Editor. Submit fee either HARRY E. WEBER by check or money order payable to the Common Philipsburg wealth of Pennsylvania. Stamps not acceptable. SAMUEL J. TRUSCOTT Individuals sending cash do so at their own risk. Dalton DAN R. SCHNABEL 111 Johnstown EDGAR W. NICHOLSON PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contribu Philadelphia tions and photos of catches from its readers. Pro KENNETH A. REID per credit will be given to contributors. Connellsville All contributors returned if accompanied by first H. R. STACKHOUSE class postage. Secretary to Board =*KT> IMPORTANT—The Editor should be notified immediately of change in subscriber's address Please give both old and new addresses Permission to reprint will be granted provided proper credit notice is given Vol. 5 No. 9 SEPTEMBER, 1936 *ANGLER7 WHAT IS BEING DONE ABOUT STREAM POLLUTION By GROVER C. LADNER Deputy Attorney General and President, Pennsylvania Federation of Sportsmen PORTSMEN need not be told that stream pollution is a long uphill fight. -

September 25, 2010 (Pages 5442-5550)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 40 (2010) Repository 9-25-2010 September 25, 2010 (Pages 5442-5550) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2010 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "September 25, 2010 (Pages 5442-5550)" (2010). Volume 40 (2010). 39. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2010/39 This September is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 40 (2010) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 40 Number 39 Saturday, September 25, 2010 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 5443—5550 Agencies in this issue The Courts Bureau of Professional and Occupational Affairs Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Labor and Industry Department of Public Welfare Department of Revenue Department of Transportation Environmental Quality Board Executive Board Fish and Boat Commission Game Commission Health Care Cost Containment Council Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission State Board of Nursing State Conservation Commission State Ethics Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporters (Master Transmittal Sheets): No. 430, September 2010 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- BULLETIN reau, 641 Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, (ISSN 0162-2137) under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publi- cation and effectiveness of Commonwealth Documents). -

2021 PA Fishing Summary

2021 Pennsylvania Fishing Summary/ Boating Handbook MENTORED YOUTH TROUT DAY March 27 (statewide) FISH-FOR-FREE DAYS May 30 and July 4 Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 TROUT OPENER April 3 Statewide Pennsylvania Fishing Summary/Boating Handbookwww.fishandboat.com www.fishandboat.com 1 2 www.fishandboat.com Pennsylvania Fishing Summary/Boating Handbook PFBC LOCATIONS/TABLE OF CONTENTS For More Information: The mission of the Pennsylvania State Headquarters Centre Region Office Fishing Licenses: Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 is to protect, conserve, and enhance P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Boat Registration/Titling: the Commonwealth’s aquatic Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Lobby Phone: (814) 359-5124 resources, and provide fishing and Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Fisheries Admin. Phone: boating opportunities. Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. (814) 359-5110 Publications: Monday through Friday Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Phone: (717) 705-7835 Monday through Friday Contents Boating Safety Regulations by Location Education Courses The PFBC Website: (All fish species) Phone: (888) 723-4741 www.fishandboat.com www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia Inland Waters............................................ 10 Pymatuning Reservoir............................... 12 Region Offices: Law Enforcement/Education Conowingo Reservoir................................ 12 Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating Delaware River and Estuary...................... -

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

To Cumberland County Sites

A NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY OF CUMBERLAND COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Update – 2005 A NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY OF CUMBERLAND COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Update – 2005 Prepared by: The Pennsylvania Science Office The Nature Conservancy 208 Airport Drive Middletown, Pennsylvania 17057 Submitted to: The Tri-County Regional Planning Commission Dauphin County Veterans Memorial Office Building 112 Market Street, Seventh Floor Harrisburg, PA 17101-2015 (717-234-2639) This project was financed in part by a grant from the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund, under the administration of the PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation and a Community Development Block Grant, under the administration of the PA Department of Community and Economic development, Office of Community Development and Housing. Subwatersheds of Cumberland County Pictures\Subwatesheds.doc Cumberland Streams (order) 0 - 1 1 - 3 3 - 7 Cumberland County Cumberland_subsheds.shp "BEAR HOLLOW" "BETTEM HOLLOW" "DEAD WOMAN HOLLOW" "HAIRY SPRINGS HOLLOW" "IRISHTOWN GAP HOLLOW" "KELLARS GAP HOLLOW" "KINGS GAP HOLLOW" "PEACH ORCHARD HOLLOW" "RESERVOIR HOLLOW" "STATE ROAD HOLLOW" "STHROMES HOLLOW" "WASP HOLLOW" "WATERY HOLLOW" ALEXANDERS SPRING CREEK BACK CREEK BERMUDIAN CREEK BIG SPRING CREEK BIRCH RUN BLOSER CREEK BORE MILL RUN BRANDY RUN BULLS HEAD BRANCH BURD RUN CEDAR RUN CENTER CREEK Forested buffers help protect streams and CLIPPINGERS RUN COLD SPRING RUN creeks from non-point sources of CONODOGUINET CREEK DOGWOOD RUN pollution and help -

Chapter 18 Natural Resources

Chapter 18 Natural Resources PHYSICAL LOCATION Shippensburg Borough and Shippensburg Township are located in the heart of Cumberland Valley, within the Ridge and Valley Province. Blue Mountain is situated towards the north (locally known as “North Mountain”) and South Mountain lies in a southeasterly direction from the Borough. The topography of the region itself can be described as gently rolling or relatively flat due to its location in a valley. The terrain has elevations ranging from approximately 640 to 720 feet. STREAMS AND WATERSHEDS The watersheds and streams in the region are shown on Figure 18.1, Water Related Features Map. There are several streams which influence the region including the Middle Spring Creek, Burd Run, and a tributary to the Middle Spring Creek (locally known as “Branch Creek”), which carries the headwaters to the Middle Spring Creek from the Dykeman Spring area. The watersheds described on Figure 18.1 drain into the Middle Spring Creek Basin, which drains into the Conodoguinet Creek Watershed, and ultimately ends up draining into the Susquehanna River through the Lower Susquehanna River Subbasin. The Lower Susquehanna River Sub-basin has a total drainage area of 5,809 square miles and includes the drainage area of the Conestoga, Conodoguinet, Swatara, Conewago, and Penn’s Creeks and several nearby streams. There are three watersheds within the region. Middle Spring Creek and Burd Run Watersheds drain almost the entire Township, while Rowe Run and Burd Run drain portions of the Borough. Dykeman’s Spring, located within the Borough, are the headwaters for the north-flowing Middle Spring Creek. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

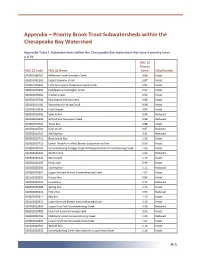

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Lancaster County Incremental Deliveredhammer a Creekgricultural Lititz Run Lancasterload of Nitro Gcountyen Per HUC12 Middle Creek

PENNSYLVANIA Lancaster County Incremental DeliveredHammer A Creekgricultural Lititz Run LancasterLoad of Nitro gCountyen per HUC12 Middle Creek Priority Watersheds Cocalico Creek/Conestoga River Little Cocalico Creek/Cocalico Creek Millers Run/Little Conestoga Creek Little Muddy Creek Upper Chickies Creek Lower Chickies Creek Muddy Creek Little Chickies Creek Upper Conestoga River Conoy Creek Middle Conestoga River Donegal Creek Headwaters Pequea Creek Hartman Run/Susquehanna River City of Lancaster Muddy Run/Mill Creek Cabin Creek/Susquehanna River Eshlemen Run/Pequea Creek West Branch Little Conestoga Creek/ Little Conestoga Creek Pine Creek Locally Generated Green Branch/Susquehanna River Valley Creek/ East Branch Ag Nitrogen Pollution Octoraro Creek Lower Conestoga River (pounds/acre/year) Climbers Run/Pequea Creek Muddy Run/ 35.00–45.00 East Branch 25.00–34.99 Fishing Creek/Susquehanna River Octoraro Creek Legend 10.00–24.99 West Branch Big Beaver Creek Octoraro Creek 5.00–9.99 Incremental Delivered Load NMap (l Createdbs/a byc rThee /Chesapeakeyr) Bay Foundation Data from USGS SPARROW Model (2011) Conowingo Creek 0.00–4.99 0.00 - 4.99 cida.usgs.gov/sparrow Tweed Creek/Octoraro Creek 5.00 - 9.99 10.00 - 24.99 25.00 - 34.99 35.00 - 45.00 Map Created by The Chesapeake Bay Foundation Data from USGS SPARROW Model (2011) http://cida.usgs.gov/sparrow PENNSYLVANIA York County Incremental Delivered Agricultural YorkLoad Countyof Nitrogen per HUC12 Priority Watersheds Hartman Run/Susquehanna River York City Cabin Creek Green Branch/Susquehanna -

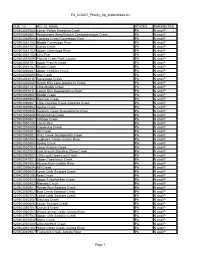

PA COAST Priority Ag Watersheds.Xls

PA_COAST_Priority_Ag_Watersheds.xls HUC_12 HU_12_NAME STATES PARAMETER 020503050505 Lower Yellow Breeches Creek PA N and P 020700040601 Headwaters West Branch Conococheague Creek PA N and P 020503060904 Cocalico Creek-Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061104 Middle Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061701 Conoy Creek PA N and P 020503061103 Upper Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061105 Lititz Run PA N and P 020503051009 Fishing Creek-York County PA N and P 020402030701 Upper French Creek PA N and P 020503061102 Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503060801 Upper Chickies Creek PA N and P 020402030608 Hay Creek PA N and P 020503051010 Conewago Creek PA N and P 020402030606 Green Hills Lake-Allegheny Creek PA N and P 020503061101 Little Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503051011 Laurel Run-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020503060902 Middle Creek PA N and P 020503060903 Hammer Creek PA N and P 020503060901 Little Cocalico Creek-Cocalico Creek PA N and P 020503050904 Spring Creek PA N and P 020503050906 Swatara Creek-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020402030605 Wyomissing Creek PA N and P 020503050801 Killinger Creek PA N and P 020503050105 Laurel Run PA N and P 020402030408 Cacoosing Creek PA N and P 020402030401 Mill Creek PA N and P 020503050802 Snitz Creek-Quittapahilla Creek PA N and P 020503040404 Aughwick Creek-Juniata River PA N and P 020402030406 Spring Creek PA N and P 020402030702 Lower French Creek PA N and P 020503020703 East Branch Standing Stone Creek PA N and P 020503040802 Little Lost Creek-Lost Creek PA N and P 020503041001 Upper Cocolamus Creek -

June 4, 2011 (Pages 2829-2922)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 41 (2011) Repository 6-4-2011 June 4, 2011 (Pages 2829-2922) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2011 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "June 4, 2011 (Pages 2829-2922)" (2011). Volume 41 (2011). 23. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2011/23 This June is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 41 (2011) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 41 Number 23 Saturday, June 4, 2011 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 2829—2922 Agencies in this issue The Courts Bureau of Professional and Occupational Affairs Department of Banking Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Public Welfare Environmental Hearing Board Fish and Boat Commission Game Commission Independent Regulatory Review Commission Patient Safety Authority Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission State Board of Chiropractic State Conservation Commission State Registration Board for Professional Engineers, Land Surveyors and Geologists Susquehanna River Basin Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporters (Master Transmittal Sheets): No. 439, June 2011 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- BULLETIN reau, 641 Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, (ISSN 0162-2137) under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publi- cation and effectiveness of Commonwealth Documents).