Teaching Jung in the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Darkening Spirit: Jung, Spirituality, Religion, by David Tacey, London and New York, Routledge, 2013, 192 Pp., £28.99/US$47.95 (Paperback), ISBN 978-0415527033

168 Book reviews The darkening spirit: Jung, spirituality, religion, by David Tacey, London and New York, Routledge, 2013, 192 pp., £28.99/US$47.95 (paperback), ISBN 978-0415527033 The Darkening Spirit is one panel of a diptych by David Tacey on contemporary spirituality. Where his other book, Gods and Diseases (Routledge, 2013) explores medical and clinical manifestations of repressed spirit, The Darkening Spirit is an analysis of today’s social and cultural spiritual landscape. Tacey contends that Jungian psychology, and in particular Jung’s approach to spirituality, is uniquely well placed among psychological theories to respond to the current spiritual condition. Indeed, he goes so far as to claim that ‘[t]he twenty-first century could well be Jung’s century, just as the twentieth was Freud’s’ (p. 2). In evidence of this, he indicates how many postmodern scientific disciplines such as physics, biology and ecology today radically depart from past linear and reductive perspectives, and even in Freudian psychoanalysis interest is now turning to those areas that had previously led to Jung’s ostracism from the psychoanalytic movement. Tacey’s main thesis is that ‘[t]he spirit of the holy has fallen into the unconscious, and we can no longer find this light by the official means, but only by arduous and difficult dialogue with the unconscious’ (p. 4). This thesis accounts for the book’s title, inspired by Heidegger’s observation that a darkening of the world implies a darkening of spirit. According to Tacey, the light of the spirit can now only be discovered in the dark, having become more faint and diffuse through its association with darkness. -

Evoking the Sacred: the Artist As Shaman

Evoking the Sacred: The Artist as Shaman Dawn Whitehand BAVA (Hons) This exegesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Arts Academy University of Ballarat PO Box 745 Camp Street, Ballarat, Victoria 3353 Australia Submitted in April 2009 The objects of [American] Indians are expressive and most decorative because they are alive, living in our experience of them. When the Indian potter collects clay, she asks the consent of the river-bed and sings its praises for having made something as beautiful clay. When she fires her pottery, to this day, she still offers songs to the fire so it will not discolor [sic] or burst her wares. And finally, when she paints her pottery, she imprints it with the images that give it life and power- because for an Indian, pottery is something significant, not just a utility but a ‘being’ for which there is as much of a natural order as there is for persons or foxes or trees.1 Jamake Highwater 1 Jamake Highwater, The Primal Mind: Vision and Reality in Indian America. (New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, Inc., 1981), 77-8. ii Abstract This thesis examines, via a feminist theoretical framework, the systems in existence that permit the ongoing exploitation of the environment; and the appropriateness of ceramics as a medium to reinvigorate dormant insights. I argue that the organic nuances expressed through clay; the earthy, phenomenological and historic ritual connotations of clay; and the tactile textured surfaces and undulating form, allows ceramics to conjure responses within the viewer that reinvigorates a sense of embedment in the Earth. -

Spirituality in the 20TH

Learning Outcomes Upon completion of this unit, it is expected that participants will be able to: WESTERN • identify the major figures, ideas, images and movements that have shaped Western spirituality in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; spirituality IN THE 20TH • reflect on the differences between spirituality and religion and why these have AND 21ST CENTURIES intensified; • identify the variety of spiritualities in the contemporary era; with Emeritus Prof. David Tacey • reflect on recent attempts within Christian spiritualities to draw on the wisdom WellSpringWellSpring July to October 2020 and practices of Eastern traditions; CENTRE WellSpring Centre, 10 Y Street Ashburton • demonstrate an understanding of mysticism, its relationship to spirituality, and explore the ‘mystical turn’ in recent times. Bookings for 2020 series Cost: $500 for the series Book and pay at www.wellspringcentre.org.au/bookings Alternatively, this unit may be taken as a credited Supervised Reading Unit in an award of the University of Divinity. Fees are then payable through FEEHelp. Dorothy Morgan Registrar, Whitley College Email: [email protected] Phone: (03) 9340 8100 If you already a student within the University of Divinity, contact the registrar at your own Home College to arrange enrolment as a Supervised Reading Unit. WellSpring CENTRE WellSpring Centre 10 Y Street Ashburton VIC 3147 w: www.wellspringcentre.org.au e: [email protected] p: (03) 9885 0277 Introduction Reading List This series adopts an historical approach to the emergence of contemporary Essential Reading: spiritualities. It begins with the rise of critical-prophetic spiritualities in [set texts recommended for purchase, paperback copies (new or used) or eBooks] Evelyn Underhill, Simone Weil and Thomas Merton. -

Of Mainstream Religion in Australia

Is 'green' religion the solution to the ecological crisis? A case study of mainstream religion in Australia by Steven Murray Douglas Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University March 2008 ii Candidate's Declaration This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. To the best of the author’s knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. Steven Murray Douglas Date: iii Acknowledgements “All actions take place in time by the interweaving of the forces of nature; but the man lost in selfish delusion thinks he himself is the actor.” (Bhagavad Gita 3:27). ‘Religion’ remains a somewhat taboo subject in Australia. When combined with environmentalism, notions of spirituality, the practice of criticality, and the concept of self- actualisation, it becomes even harder to ‘pigeonhole’ as a topic, and does not fit comfortably into the realms of academia. In addition to the numerous personal challenges faced during the preparation of this thesis, its very nature challenged the academic environment in which it took place. I consider that I was fortunate to be able to undertake this research with the aid of a scholarship provided by the Fenner School of Environment & Society and the College of Science. I acknowledge David Dumaresq for supporting my scholarship application and candidature, and for being my supervisor for my first year at ANU. Emeritus Professor Valerie Brown took on the role of my supervisor in David’s absence during my second year. -

Spirituality 2020 3

Learning Outcomes Upon successful completion of this unit, it is expected that students will be able to: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the nature and role of spirituality in Australian AUSTRALIAN society; 2. Identify and analyse the role and nature of spirituality in Indigenous Australian cultures; spirituality 2020 3. Critically reflect on the tension between indigenous cultures and non-indigenous cultures, based on sacred and secular assumptions and values; with Emeritus Prof. David Tacey 4. Critically consider the process and history of secularisation in Australia and its WellSpringWellSpring February to June 2020 CENTRE impact on Christianity and other religions; WellSpring Centre, 10 Y Street Ashburton 5. Demonstrate a critical understanding of the inter-relationship between emerging spiritualities and the multicultural and multi-faith complexity of Australian society. 2020 Costs This unit will be offered for under-graduate (Unit code: DS3035W) or post-graduate (Unit code: DS9035W) credit. Enrolment for Academic Credit: Per University of Divinity schedule (single unit). If students enrol through University of Divinity, FEE-Help may be available to cover tuition fees. All enrolment fees for academic credit are payable to University of Divinity through your RTI (Recognised Teaching Institution). Auditing: Cost $500. No FEE-Help is available for auditing students. Entrance for 2020 course To enrol for this unit as a new student, either for academic credit or as an auditing student, please contact Dorothy Morgan, Registrar at Whitley College at registrar@ whitley.edu.au or on (03) 9340 8100. If you already a student within the University of Divinity, contact the registrar at your own Home College to arrange enrolment. -

Newsletter Volume 78 - Term 3, 2015

The Centre for Ethics Newsletter Volume 78 - Term 3, 2015 Richard Holloway, former Bishop of Breaking open the myth Edinburgh, who wrote in How to Read Where might this approach take the Bible, ‘Unimaginative literalists those who would follow the lead have destroyed the reputation of the of David Tacey? He says the first Bible by insisting on its factual truth task is to break open the myth. This rather than encouraging us to read breaking open is a necessary it metaphorically’. beginning. But what happens then? Tacey encourages the reader Mesmerised by images to be open to the myth’s interior Tacey has said he wants this book meaning. Simply to break open to cause discussion. In this, I do the myth without engaging in the not think he will be disappointed. hard work of looking for its inner He sees Australia as a theological meaning is, according to Tacey, an backwater, where the question of act of vandalism. It discounts any how we read the Bible has been sense that traditions matter and it ignored or denied. He acknowledges has no educational value. He enlists David Tacey that some theologians in this country the philosopher Karl Jaspers to David Tacey is Emeritus Professor have hinted at metaphorical content back him up, ‘Only he or she has of Literature at La Trobe University, but not been able to discuss it in the right to demythologise who Melbourne and Research Professor plain language. He says too many retains the truth contained in the at the Australian Centre for theologians are trapped in literalism; symbolic expression.’ But what is Christianity and Culture, Canberra. -

![David Tacey's New Animism Seminar[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5660/david-taceys-new-animism-seminar-1-2015660.webp)

David Tacey's New Animism Seminar[1]

1 Dear Colleagues, The Executive Committee is pleased to launch the first seminar in the Issues in Jungian Psychology Series with David Tacey’s paper, ‘Toward A New Animism: Jung, Hillman and Analytical Psychology.’ From David some points to consider: The ecological crisis of the contemporary world has urged upon us anew kind of animism, in which the things of the world are alive, animated, spirited, mainly because the body of the world is experiencing pain, pathological symptoms and suffering; the psyche of the world or anima mundi is being discovered in the same way in which psyche was first discovered in suffering individuals. Hillman’s work draws out contradictions in Jung’s theorizing, and privileges Jung’s post‐Cartesian vision and its affirmation of an new kind of animism, which is easily mistaken as pre‐modern animism, and hence as regressive. Hillman’s ‘archetypal psychology’ is an attempt to re‐appropriate what had been left out of ‘Jungian’ or ‘analytical psychology’, but what he re‐appropriates seems so foreign to established views that it is treated as alien and disruptive. This paper raises several issues that may be found at the end of the paper after references. Best wishes, Maryann Dear Colleagues, We have had some thought provoking and inspiring discussions of late from many contributors under the headings of TERMS and ANTIMONY. The spectrum of perception the IAJS membership hold collectively on Jung and what comprises Jungian Studies continues to demonstrate ongoing frontiers on both these topics. I suspect some of these debates will find a new frame in the first seminar of the Issues In Jungian Psychology Series that commences on October 1st. -

How to Read Jung by David Tacey

A Sea of Faith Network (NZ) Review from Newsletter 70, March 2007 The Ultimate Right-Brainer How To Read Jung David Tacey Granta Books London 2006 In the experience of this reviewer, there are only three available attitudes towards Carl Jung: you love him, you hate him, or you have never heard of him. Indifference is not an option. I mostly agree with the first attitude — but that does not mean that I understand Jung. I think that my attitude comes from thinking, or better, feeling that I sort of align with what he is saying. David Tacey was a keynote speaker at the 2006 New Zealand Conference and is the author of eight books and eighty published essays on Jungian studies, spirituality, and culture. Books in press include The Idea of the Numinous (London: Routledge 2006). David is Associate Professor in the School of Arts and Critical Enquiry, La Trobe University, Melbourne. He teaches courses on spirituality, Jungian psychology, and literature. He is on the international faculty of the C. G. Jung Institute in Zurich, where he presents short courses on his current research. We need this book — How To Read Jung — to launch into what is a complex subject and Tacey writes lucidly. He tackles Jung’s big themes head-on taking us through symbols and dreams, then on to the ‘second self’ which is crushed by dogma but set free by artistic creativity. Myth, the ‘dark side’ (to give George Lucas’ rendering of The Shadow) , Anima/Animus, Archetypes and Individuation are all there. At barely 100 pages of text this is a first class way into to Jungian thought and is highly recommended. -

JO 2018 Brochure Full Program Status 20171009.Docx 1 / 15

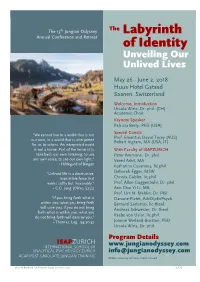

The The 13th Jungian Odyssey Labyrinth Annual Conference and Retreat of Identity Unveiling Our Unlived Lives May 26 - June 2, 2018 Huus Hotel Gstaad Saanen, Switzerland Welcome, Introduction Ursula Wirtz, Dr. phil. (CH) Academic Chair Keynote Speaker Patricia Berry, PhD (USA) Special Guests “We cannot live in a world that is not Prof. Emeritus David Tacey (AUS) our own, in a world that is interpreted Robert Ingram, MA (USA, IT) for us by others. An interpreted world is not a home. Part of the terror is to With Faculty of ISAPZURICH take back our own listening, to use Peter Ammann, Dr. phil. our own voice, to see our own light.” Vered Arbit, MA • Hildegard of Bingen Katharina Casanova, lic.phil. Deborah Egger, MSW "Unlived life is a destructive, irresistible force that Christa Gubler, lic.phil. works softly but inexorably." Prof. Allan Guggenbühl, Dr. phil. • C.G. Jung (CW10, §252) Ann Chai Yi Li, MA Prof. Urs H. Mehlin, Dr. Phil. “If you bring forth what is Dariane Pictet, AdvDipExPsych within you, what you bring forth Bernard Sartorius, lic.theol. will save you, if you do not bring Andreas Schweizer, Dr. theol. forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” Ilsabe von Uslar, lic.phil. • Thomas, Log. 94:30-32 Joanne Wieland-Burston, PhD Ursula Wirtz, Dr. phil. Program Details ISAPZURICH INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OF www.jungianodyssey.com ANALYTICAL PSYCHOLOGY ZURICH [email protected] AGAP POST-GRADUATE JUNGIAN TRAINING Photo: Courtesy of Huus Hotel Gstaad JO 2018_Brochure_Full Program_Status_20171009.docx 1 / 15 Since 2006, participants world-wide have acclaimed the The Jungian Odyssey 2018 Jungian Odyssey—ISAPZURICH’s annual spring semester retreat that opens to the general public our post-graduate level program with our faculty and guest scholars. -

Jung and the New Age: a Study in Contrasts”, the Round Table Press Review (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Vol., No., April 1998, Pp.1-11

This essay has been previously published: in essay form: “Jung and the New Age: A Study in Contrasts”, The Round Table Press Review (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Vol., No., April 1998, pp.1-11. Also published as a chapter in David Tacey, Jung and the New Age, London and New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2001. Jung and the New Age: A Study in Contrasts David Tacey: email: [email protected] Jung’s name has been associated with the New Age for about three decades, but now his alleged “influence” on this movement is being formally proposed and articulated. In New Age Spirituality, Duncan Ferguson argues that Jung has played a major role in the development of this popular spirituality,1 and more recently in The New Age Movement sociologist Paul Heelas claims that Jung is one of “three key figures” (the others being Blavatsky and Gurdjieff) who is responsible for the existence of the movement.2 In similar vein, Nevill Drury maintains that “Jung’s impact on New Age thinking has been enormous, greater, perhaps, than many people realise.”3 Everywhere the claim is being made that the New Age movement is a product of Jungian interest, and today spiritually oriented therapists from a diverse range of fields all claim to be Jungian, or refer to Jung as their spiritual ancestor, scientific authority, inspiration, or source. The task of this paper is to critically evaluate how “Jungian” the New Age is, and to explore the similarities and differences between New Age spirituality and Jungian metapsychology. Jung clearly has several points in common with the New Age. -

Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy the Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing

9 No. Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Vicki Grieves Discussion Paper Series: Discussion Paper Aboriginal Spirituality provides a philosophical baseline for Indigenous knowledges development in Australia. It is Aboriginal knowledges that build the capacity to enhance the social and emotional wellbeing for Aboriginal people now living within a colonial regime. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health Discussion Paper Series: No. 9 Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Vicki Grieves © Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009 CRCAH Discussion Paper Series – ISSN 1834–156X ISBN 978–0–7340–4102–9 First printed in December 2009 This work has been published as part of the activities of the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (CRCAH). The CRCAH is a collaborative partnership partly funded by the Cooperative Research Centre Program of the Australian Government Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, or by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community organisations subject to an acknowledgment of the source and no commercial use or sale. Reproduction for other purposes or by other organisations requires the written permission of the copyright holder(s). Additional copies of this publication (including a pdf version on the CRCAH website) can be obtained from: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health PO Box 41096, Casuarina NT 0811 AUSTRALIA T: +61 8 8943 5000 F: +61 8 8943 5010 E: [email protected] W: www.crcah.org.au Authors: Vicki Grieves Managing Editor: Jane Yule Copy Editor: Cathy Edmonds Cover photograph: Photograph of Alfred Coolwell by Vicki Grieves Original Design: Artifishal Studios Formatting and Printing: InPrint Design For citation: Grieves, V. -

Gods and Diseases Making Sense of Our Physical and Mental Wellbeing

About the Author Dr David Tacey is Associate Professor in Humanities at La Trobe University, Melbourne. He is the author of twelve books, including Re-Enchantment: The New Australian Spirituality (2000), The Spirituality Revolution (2003) and Edge of the Sacred (2009). In the 1970s, David studied literature, psychology and philosophy at Flinders and Adelaide Universities, and in the 1980s he completed post-doctoral studies in psychoanalysis and religion in the United States. He was a Harkness Postdoctoral Fellow of the Commonwealth Fund, New York, and his studies were supervised by James Hillman and Thomas Moore. He has taught in various Australian, American and British universities, and is on the editorial boards of several international journals on analytical psychology and religious studies. He is a public intellectual who is often invited to address contemporary issues, including ecological awareness, mental health, spirituality and Aboriginal Australia. His books have been translated into several languages, including Cantonese, Korean, Spanish, Portuguese and French. God and Disease GJ 3pp.indd 1 8/12/10 2:06 PM Also by David Tacey The Jung Reader (London: Routledge, 2011) Uncertain Places: Cultural Complexes in Australasia, edited by Amanda Dowd, Craig San Roque and David Tacey (New Orleans: Spring Journal Books, 2011) Edge of the Sacred: Jung, Psyche, Earth, Revised International Edition (Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon, 2009) Re-Enchantment: The New Australian Spirituality (Sydney: HarperCollins, 2000) How to Read Jung (London: