DRAFT Submission Select Committee Into Local Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes Wa & Nt Division Meeting

MINUTES WA & NT DIVISION MEETING Karratha Airport THURSDAY 12 MAY at 1300 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- OPENING AND WELCOME ADDREESS Welcoming address by NT Chair Mr Tom Ganley, acknowledging Mayor, City of Karratha Peter Long and AAA National Chair Mr Guy Thompson. Welcome to all attendees and acknowledge of the local indigenous people by Mayor Peter Long followed by a brief background on the City of Karratha and Karratha Airport. 1. ATTENDEES: Adam Kett City of Karratha Mike Gough WA Police Protection Security Unit Allan Wright City of Karratha Mitchell Cameron Port Hedland International Airport Andrew Shay MSS Security Nat Santagiuliana PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd Bob Urquhart City of Greater Geraldton Nathan Lammers Boral Asphalt Brett Karran APEX Crisis Management Nathanael Thomas Aerodrome Management Services Brian Joiner City of Karratha Neil Chamberlain Bituminous Products Daniel Smith Airservices Australia Nick Brass SunEdison Darryl Tonkin Kalgoorlie-Boulder Airport Peter Long City of Karratha Dave Batic Alice Springs Airport Rob Scott Downer Eleanor Whiteley PHIA operating Company Rod Evans Broome International Airport Guy Thompson AAA / Perth Airport Rodney Treloar Shire of Esperance Jennifer May City of Busselton Ross Hibbins Vaisala Jenny Kox Learmonth Airport, Shire of Exmouth Ross Loakim Downer Josh Smith City of Karratha Simon Kot City of Karratha Kevin Thomas Aerodrome -

The Incident Assessment Team (IAT) Karratha Airport

The Incident Assessment Team (IAT) Karratha Airport INCIDENT Revision No. V2-01 ASSESSMENT TEAM (IAT) Effective Date: August 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Process for Establishing the IAT 5 3. Operations of the IAT 6 4. Stakeholder Responsibilities 8 5. Incident Assessment Team Control Sheet 12 6. Category 2 Incident Lead Stakeholder Guide 13 7. IAT Meeting Agency Contact List 14-16 8. Attendance List 17 9. Meeting Guide 18 10. IAT Meeting Flowchart 19 11. IAT Process Flowchart 20 The Incident Assessment Team (IAT) Page 2 of 20 This electronic document is a controlled document August 2014 INCIDENT Revision No. V2-01 ASSESSMENT TEAM (IAT) Effective Date: August 2014 1. INTRODUCTION The intent of this model is to provide a coordinated response to an incident in a timely and appropriate manner to enable restoration of normal operations. The primary stakeholders that may be involved in responding to and resolving incidents, events and threats are: The Airport owner; Airline Operators and/or appointed representatives; Police, Fire and rescue Critical Service providers: Council, Hydrant & Fuel; Airservices Australia; and Other government agencies as appropriate i.e. Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, etc. The model allows for any of the above agencies to request an IAT meeting. The Airport Security Contact Officer / Airport Compliance Coordinator would establish the IAT on behalf of the stakeholders. The IAT does not have to physically meet. It can be convened via teleconference if the matter is time critical or stakeholders are unable to attend in person. Following the IAT meeting the incident would continue to be managed by existing operational processes as appropriate. -

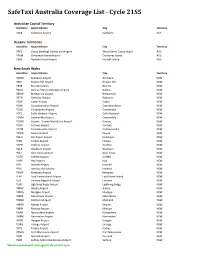

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Aaa Submission Wa Legislative Assembly Economics and Industry Standing Committee Inquiry Into Regional Airfares in Western Australia

REGAIR Submission 70 Recv'd 28 July 2017 1982 • 2017 YEARS AAA SUBMISSION WA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ECONOMICS AND INDUSTRY STANDING COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO REGIONAL AIRFARES IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA 28 JULY 2017 REGAIR Submission 70 Recv'd 28 July 2017 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIAN AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION The Australian Airports Association The AAA represents the interests of The AAA facilitates co-operation among (AAA) is a non-profit organisation that over 380 members. This includes more all member airports and their many and was founded in 1982 in recognition of than 260 airports and aerodromes varied partners in Australian aviation, Australia wide – from the local country whilst contributing to an air transport the real need for one coherent, cohesive, community landing strip to major system that is safe, secure, environmentally consistent and vital voice for aerodromes international gateway airports. responsible and efficient for the benefit of and airports throughout Australia. all Australians and visitors. The AAA also represents more than 120 aviation stakeholders and The AAA is the leading advocate for organisations that provide goods and appropriate national policy relating to services to airports. airport activities and operates to ensure regular transport passengers, freight, and the community enjoy the full benefits of a progressive and sustainable airport 2 industry. REGAIR Submission 70 Recv'd 28 July 2017 CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Introduction 3 Regional tourism in Western Australia 4 Western Australian aviation markets 5 Figure 1: Annual -

Attachment 2

Contact us Connecting Australia Australian Airports Association Unit 9, 23, Brindabella Circuit Brindabella Park ACT 2609 The economic and social Tel: +61 6230 1110 contribution of Australia's airports Fax: +61 6230 1367 C Email: [email protected] Prepared for Australian Airports Association M www.airports.asn.au May 2012 Y CM Deloitte Access Economics MY Level 1, 9 Sydney Avenue CY Barton ACT 2600 CMY PO Box 6334 Kingston ACT 2604 K Australia Tel: +61 2 6175 2000 Fax: +61 2 6175 2001 Email: [email protected] www.deloitteaccesseconomics.com.au The economic and social contribution of Australia’s airports Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................... i Key points ................................................................................................................................. ii Executive summary ................................................................................................................... v 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2 Australia’s airport sector ................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Composition and structure of the industry ........................................................................ 5 2.3 Role of airports in the economy ....................................................................................... -

WA Aviation Strategy 2020 DRAFT DRAFT

DRAFT WA Aviation Strategy 2020 DRAFT DRAFT Minister’s Foreword Access to affordable airfares is central to the liveability of our regional towns. Regional air services help reduce isolation, are essential to health services, and play a key role in supporting economic development and job creation in the regions. The Hon. Rita Saffioti MLA Minsiter for Transport Western Australia’s isolation and sheer distances Aviation has, and will continue to play a key make aviation an integral part of our State’s role in our State’s prosperity. Efficient and economic and social wellbeing. affordable air services are crucial not only to the community but also to the tourism and This draft WA Aviation Strategy 2020 (the resources sectors that rely on air services to Strategy) is a blueprint for advancing aviation in get in and out of Perth. Western Australia and sets out a practical policy approach for the aviation industry in WA into the Aviation in WA operates in a complex future. The McGowan Government came into environment involving airlines, airports, industry, office with a commitment to address community community and all levels of government. At concerns about high regional airfares, and this a State Government level, our policies and Strategy delivers on that commitment. regulatory environment need to foster airfares that are affordable to those who rely on Access to affordable airfares is central to the them, and we need to ensure that our airport liveability of our regional towns. Regional air infrastructure is fit for purpose and continues to services help reduce isolation, are essential support future growth in the aviation industry. -

Submission 52

The Qantas Group Submission Productivity Commission Inquiry into the Economic Regulation of Airport Services April 2011 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction The Qantas Group remains committed to a process of constructive engagement between airports and airport users in Australia. Since the introduction of light handed monitoring there has been progress with certain airports towards a more appropriate commercial negotiating approach. However, the Qantas Groups’ experience continues to indicate that reasonable commercially negotiated outcomes with airports are the exception rather than the rule. Where such agreements have been reached they are inevitably the result of protracted negotiations often taking years. Airports are natural monopolies and the current light handed monitoring approach to regulation has been ineffective in preventing the operators of major airports from exerting significant market power in the provision and pricing of airport facilities and services. Whilst the Government’s Aeronautical Pricing Principles were intended to serve as a guide for the pricing of aeronautical services at the non-monitored capital city and larger regional airports, many of these airports also exert significant market power and exhibit behaviours that are not consistent with those of service providers operating in a competitive environment. The current regulatory regime provides no disincentive at all for the major airports in charging demonstrably excessive rates for any core aviation facilities that sit outside the current light handed regime. In particular, excessive lease costs for critical infrastructure such as airline offices, lounges, hangars, maintenance facilities, check in counters, service desks and staff car parking all sit outside any protection provided by the current regime. Airlines, and indeed airports, cannot function without these facilities and yet no protection is afforded to airlines in relation to the provision of these services by airports. -

Lagardere Participating Locations 2019

Adelaide Airport Store Location Aelia Duty Free Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Icons Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Link Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport MAC Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Relay Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Tech2Go Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Avalon Airport Store Location Relay Domestic Terminal Avalon Airport Aelia Duty Free International Terminal Avalon Airport Brisbane Airport Store Location Tech2Go Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport Trader & Co Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport Watermark Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport Ballina Airport Store Location Relay Ballina Byron Gateway Airport Canberra Airport Store Location Relay Canberra Airport Cairns Airport Store Location Discover Domestic Terminal Cairns Airport MAC Domestic Terminal Cairns Airport Newslink/Hub Domestic Terminal Cairns Airport Aelia Duty Free International Terminal Cairns Airport Australian Made International Terminal Cairns Airport Discover International Terminal Cairns Airport Discover TNQ International Terminal Cairns Airport Purely Merino International Terminal Cairns Airport Relay International Terminal Cairns Airport Karratha Airport Store Location Café Karratha Airport LINK Karratha Airport Page 1 of 3 12 Shelley Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia ABN 92 108 952 085 Launceston Airport Store Location The Launceston Store Launceston Airport Melbourne Airport Store Location Newslink Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Newslink/Hub Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Tech2Go Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Watermark Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Icons Terminal 2 Melbourne Airport -

Collection Name

THE INSTITUTION OF ENGINEERS, AUSTRALIA (WESTERN AUSTRALIAN DIVISION) WA ENGINEEERING EXCELLENCE AWARDS 1909 Western Australian Institution of Engineers (WAIE) founded 1910 Inaugural year of operation 1911 WAIE incorporated 1919 Engineers Australia formed, WAIE a foundation member 1920 WAIE name changed to the Perth Division of Engineers Australia 1927 5th Annual Engineering Conference hosted by Perth Division 1969 Perth Division name changed to the Western Australia Division 1979 Diamond Jubilee Conference hosted by WA Division 2000 WA Division had over 7,000 members Source: <http://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/divisions/western-australia-division/about-us/about-us_home.cfm> PRIVATE ARCHIVES MANUSCRIPT NOTE (MN2836; ACC 7741A, 9594A, 9595A) SUMMARY OF CLASSES WA ENGINEERING EXCELLENCE AWARDS Acc. No. DESCRIPTION ENTRIES FOR ENGINEERING EXCELLENCE AWARDS 7741A/1 1987 Western Australia and 1988 National:- a) BHP Engineering – Mt Newman Mining Company Pty Ltd, North Wall Geotechnical Study; b) Marine and Harbours Western Australia Engineering Division – Hillarys Boat Harbour; c) Telecom Australia WA – Telecommunication for the America’s Cup; d) BHP Engineering – Blast Resistant Enclosures for Liquid natural Gas Plant, North West Shelf Project; e) Lincolne Scott API – Lighting Installation , Esplanade Plaza Hotel, Fremantle; f) Lincolne Scott API – The Casino in Burswood Island Resort, Perth; h) Kinhill Engineers Ltd – Frozen Fresh Fries and Peas Processing Facility, Manjimup (Edgell Birds Eye); i) Building Management Authority of Western -

Location Address Suburb State Postcode AUSTRALIA

AUSTRALIA Location Address Suburb State Postcode Canberra Airport Terminal Building Pialligo ACT 2609 Canberra Mantra Hotel Mantra on Northbourne 84 Northbourne Canberra ACT 2612 Fyshwick Downtown 27 Kembla St Fyshwick ACT 2609 Alexandria Downtown Unit 6 221-223 O'Riordan St Mascot NSW 2020 Arncliffe 129 Princes Highway Arncliffe NSW 2205 Artarmon 77 Whiting St Artarmon NSW 2064 Brookvale 47 Mitchell Rd Brookvale NSW 2100 Darling Harbour 10/209 Harris St Pyrmont NSW 2009 Newcastle Unit 2 122 Hannell St Wickham NSW 2293 Sydney Airport Keith Smith Ave Mascot NSW 2020 Sydney City 65 William St Darlinghurst NSW 2010 Taren Point Downtown 91-93 Cawarra Road Caringbah NSW 2229 Williamtown Airport Terminal Building Williamtown NSW 2314 Zetland Audi Centre, Level 3 2A Defries Ave Zetland NSW 2017 Alice Springs Airport Santa Teresa Rd Alice Springs NT 0870 Alice Springs Downtown 8 Kidman Street Alice Springs NT 0871 Ayers Rock Airport Terminal Building Yulara NT 0872 Ayers Rock Downtown Resort Shopping Centre 201 Yulara Dr Yulara NT 0872 Darwin Airport Terminal Building Darwin Airport NT 0812 Darwin Downtown Shop 41 Mitchell Centre 55-59 Mitchell St Darwin NT 0820 Katherine Downtown Giles Street Katherine NT 0850 Biloela / Thangool Airport 57-59 Dawson Hwy Biloela QLD 4715 Brisbane Airport Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport QLD 4007 Brisbane City 55 Charlotte St Brisbane City QLD 4000 Cairns Airport Airport Avenue Cairns QLD 4870 Cairns Central 147 Lake St Cairns QLD 4870 Cairns City Cairns Square Shopping Centre 1-21 Cairns QLD 4870 Currumbin -

Annual Electors' Meeting

ANNUAL ELECTORS’ MEETING MINUTES The Annual Electors’ Meeting was held in the Council Chambers, Welcome Road, Karratha, on Monday, 14 December 2020 ________________________ CHRIS ADAMS CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER No responsibility whatsoever is implied or accepted by the City of Karratha for any act, omission or statement or intimation occurring during Council or Committee Meetings. The City of Karratha disclaims any liability for any loss whatsoever and howsoever caused arising out of reliance by any person or legal entity on any such act, omission or statement or intimation occurring during Council or Committee Meetings. Any person or legal entity who acts or fails to act in reliance upon any statement, act or omission made in a Council or Committee Meeting does so at that persons or legal entity’s own risk. In particular, and without derogating in any way from the broad disclaimer above, in any discussion regarding any planning application or application for a license, any statement or intimation of approval made by any member or Officer of the City of Karratha during the course of any meeting is not intended to be and is not taken as notice of approval from the City of Karratha. The City of Karratha warns that anyone who has any application lodged with the City of Karratha must obtain and should only rely on WRITTEN CONFIRMATION of the outcome of the application, and any conditions attaching to the decision made by the City of Karratha in respect of the application. Signed: _________________________ Chris Adams - Chief Executive Officer DECLARATION OF INTERESTS (NOTES FOR YOUR GUIDANCE) (updated 13 March 2000) A member who has a Financial Interest in any matter to be discussed at a Council or Committee Meeting, which will be attended by the member, must disclose the nature of the interest: (a) In a written notice given to the Chief Executive Officer before the Meeting or; (b) At the Meeting, immediately before the matter is discussed. -

Wandoo Field Oil Spill Contingency Plan Document 2: Oil Pollution Emergency Plan Wan-2000-Rd- 0001.02

VERMILION OIL & GAS AUSTRALIA WANDOO FIELD OIL SPILL CONTINGENCY PLAN DOCUMENT 2: OIL POLLUTION EMERGENCY PLAN WAN-2000-RD- 0001.02 Revision Date Originator Checker Approver 17 17 Feb 2021 Environmental Advisor HSE Manager Managing Director SIGNATURES ON APPROVAL FORM 22/02/2021 VERMILION OIL & GAS AUSTRALIA Title: Wandoo Field Oil Spill Contingency Plan – Oil Pollution Emergency Plan Number: WAN-2000-RD-0001.02 Revision: 17 Date: 17 February 2021 Revision history Revision Date Description 7 29.08.14 NOPSEMA comments 8 16.10.14 NOPSEMA comments 9 07.10.16 Issued for Use 10 06.02.17 NOPSEMA comments 11 18.04.17 NOPSEMA comments 12 21.07.17 Issued for Use 13 16.11.18 Routine review 14 03.01.20 Issued for NOPSEMA Acceptance 15 14.08.20 NOPSEMA comments addressed 16 04.12.20 ICT recource plan 17 17.02.21 Revised ICT recource and dispesant plan Distribution list Copy no. Position Hard copy E copy 1 Master copy – VOGA Document Control X X 2 VOGA Managing Director X 4 VOGA HSES Manager X 5 Wandoo Field Superintendent X X 6 VOGA Incident Commander X X 7 ICT Planning Chief X X 8 ICT Logistics Chief X X 9 ICT Finance Chief X 10 ICT Operations Chief X 11 ICT Safety Officer X 12 ICT Stakeholder Liaison Officer X 13 ICT Public Information Officer X 14 Vermilion Corporate Command Operations Team X 15 VOGA Well Construction QHSE Advisor X 16 VOGA Environmental Advisor X 17 MODU Offshore Installation Manager X X Page ii VERMILION OIL & GAS AUSTRALIA Title: Wandoo Field Oil Spill Contingency Plan – Oil Pollution Emergency Plan Number: WAN-2000-RD-0001.02