PASSERIFORMES Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Phthiraptera: Ischnocera), with an Overview of the Geographical Distribution of Chewing Lice Parasitizing Chicken

European Journal of Taxonomy 685: 1–36 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.685 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2020 · Gustafsson D.R. & Zou F. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:151B5FE7-614C-459C-8632-F8AC8E248F72 Gallancyra gen. nov. (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera), with an overview of the geographical distribution of chewing lice parasitizing chicken Daniel R. GUSTAFSSON 1,* & Fasheng ZOU 2 1 Institute of Applied Biological Resources, Xingang West Road 105, Haizhu District, Guangzhou, 510260, Guangdong, China. 2 Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resource Utilization, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Conservation and Utilization, Guangdong, China. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:8D918E7D-07D5-49F4-A8D2-85682F00200C 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A0E4F4A7-CF40-4524-AAAE-60D0AD845479 Abstract. The geographical range of the typically host-specific species of chewing lice (Phthiraptera) is often assumed to be similar to that of their hosts. We tested this assumption by reviewing the published records of twelve species of chewing lice parasitizing wild and domestic chicken, one of few bird species that occurs globally. We found that of the twelve species reviewed, eight appear to occur throughout the range of the host. This includes all the species considered to be native to wild chicken, except Oxylipeurus dentatus (Sugimoto, 1934). This species has only been reported from the native range of wild chicken in Southeast Asia and from parts of Central America and the Caribbean, where the host is introduced. -

Evolutionary Genetics and the Major Histocompatibility Complex of New Zealand Robins (Petroicidae)

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Evolutionary Genetics and the Major Histocompatibility Complex of New Zealand Robins (Petroicidae) Hilary C. Miller A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular BioSciences at Massey University, New Zealand June 2003 The founding black robin pair, Old Blue (above), and Old Yellow (right) Photo: Rod Morris The South Island robin Photo: J. Kendrick (DOe) Abstract The genes ofthe major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are highly polymorphic and play a direct role in disease resistance. Loss of variation at MHC loci may increase extinction risk in endangered species, due to an inability to combat a range of pathogens. In this thesis, the evolution of class II B MHC genes is investigated, and levels of variation at these loci are measured in two species of New Zealand robin, the endangered Chatham Island black robin (Petroica traversi), and the non-endangered South Island robin (Petroica australis australis). Transcribed class II B MHC loci from both black robin and South Island robin were characterised prior to analysis ofMHC variation. To this end, a non-lethal protocol fo r isolation of transcribed sequences from blood using 3'RA CE and RT-PCR was developed. Four class II B cDNA sequences were isolated frombla ck robin, and eight sequences were isolated from the South Island robin, indicating there are at least fo ur class II B loci. -

New Data on the Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) of Passerine Birds in East of Iran

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244484149 New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran ARTICLE · JANUARY 2013 CITATIONS READS 2 142 4 AUTHORS: Behnoush Moodi Mansour Aliabadian Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 3 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 110 PUBLICATIONS 393 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ali Moshaverinia Omid Mirshamsi Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 10 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 152 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Omid Mirshamsi Retrieved on: 05 April 2016 Sci Parasitol 14(2):63-68, June 2013 ISSN 1582-1366 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran Behnoush Moodi 1, Mansour Aliabadian 1, Ali Moshaverinia 2, Omid Mirshamsi Kakhki 1 1 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, Iran. 2 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology, Iran. Correspondence: Tel. 00985118803786, Fax 00985118763852, E-mail [email protected] Abstract. Lice (Insecta, Phthiraptera) are permanent ectoparasites of birds and mammals. Despite having a rich avifauna in Iran, limited number of studies have been conducted on lice fauna of wild birds in this region. This study was carried out to identify lice species of passerine birds in East of Iran. A total of 106 passerine birds of 37 species were captured. Their bodies were examined for lice infestation. Fifty two birds (49.05%) of 106 captured birds were infested. Overall 465 lice were collected from infested birds and 11 lice species were identified as follow: Brueelia chayanh on Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), B. -

Monitoring Program – Fauna

Procedure Document No. 2663 Document Title Monitoring Program – Fauna Area HSE Issue Date Major Process Environment Sub Process Authoriser Jacqui McGill – Asset President Version Number 19 Olympic Dam 1 SCOPE..................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Responsible ODC personnel ........................................................................................... 2 1.2 Review and modification ................................................................................................. 2 2 DETAILED PROCEDURE ........................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Feral and abundant species ............................................................................................ 3 2.2 ‘At-risk’ fauna – Category 1a ........................................................................................... 3 2.3 ‘At-risk’ fauna – Categories 1b and 2 ............................................................................... 4 2.4 Fauna losses .................................................................................................................. 5 3 COMMITMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Reporting ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Summary of commitments.............................................................................................. -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

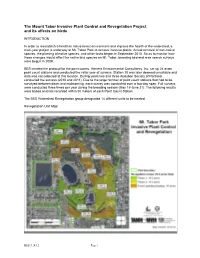

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Additional Records of Passerine Terrestrial Gaits

ADDITIONAL RECORDS OF PASSERINE TERRESTRIAL GAITS GEORGE A. CLARK, JR. The varied methods of locomotion in birds pose significant problems in behavior, ecology, adaptation, and evolution. On the ground birds progress with their legs moving either synchronously (hopping) or asynchronously (walking, running) as the extreme conditions. Relatively terrestrial species often have asynchronous gaits, whereas primarily arboreal species are typically synchronous on the ground. Particularly important earlier studies on passerines are Kunkels’ (1962) comparative behavioral survey and Riiggebergs’ (1960) analysis of the morphological correlates of gaits. Over several years I have noted gaits for 47 passerine species in the U.S., En- gland, and Kenya, and have examined many references. I here sum- marize behavioral records for families not mentioned by Kunkel (1962) and also for species with gaits markedly unlike those of confamilial species discussed by him. My supplementary review is selective rather than ex- haustive with the aim of indicating more fully the distribution of gaits among the passerine families. Regional handbooks, life history studies, and other publications contain numerous additional records, but I know of none that negate the conclusions presented here. J. S. Greenlaw (in prep.) has reviewed elsewhere the passerine double-scratch foraging be- havior that has at times previously been discussed in connection with gaits (e.g., in Hailman 1973). VARIATION WITHIN SPECIES Gaits often vary within a species (Kunkel 1962, Hailman 1973, Schwartz 1964, Gobeil 1968, Eliot in Bent 1968:669-670, this study). As an addi- tional example, I have seen Common Grackles (Quisc&s quiscula) hop in contrast to their usual walk. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds

B BIO VIEW Curator Notes From the Brink of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds In terms of conservation efforts, the Rio Grande Zoo is a rare breed in its own right, using its expertise to preserve and breed species whose numbers have dwindled to almost nothing both in the wild and in captivity. Recently, we took charge of a little over one-tenth of the entire world’s population of Socorro doves which have been officially extinct in the wild since 1978 and are now represented by only 100 genetically pure captive individuals that have been carefully preserved in European institutions. Of these 100 unique birds, 13 of them are now here at RGZ, making us the only holding facility in North America for this species and the beginning of this continent’s population for them. After spending a month in quarantine, the birds arrived safe and sound on November 18 from the Edinburgh and Paignton Zoos in England. Other doves have been kept in private aviaries in California, but have been hybridized with the closely related mourning dove, so are not genetically pure. History and Background Socorro doves were once common on Socorro Island, the largest of the four islands making up the Revillagigedo Archipelago in the East- ern Pacific ocean about 430 miles due west of Manzanillo, Mexico and 290 miles south of the tip of Baja, California. Although the doves were first described by 19th century American naturalist Andrew Jackson Grayson, virtually nothing is known about their breeding behavior in the wild. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 104, NUMBER 7 THE FEEDING APPARATUS OF BITING AND SUCKING INSECTS AFFECTING MAN AND ANIMALS BY R. E. SNODGRASS Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine Agricultural Research Administration U. S. Department of Agriculture (Publication 3773) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION OCTOBER 24, 1944 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 104, NUMBER 7 THE FEEDING APPARATUS OF BITING AND SUCKING INSECTS AFFECTING MAN AND ANIMALS BY R. E. SNODGRASS Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine Agricultural Research Administration U. S. Department of Agriculture P£R\ (Publication 3773) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION OCTOBER 24, 1944 BALTIMORE, MO., U. S. A. THE FEEDING APPARATUS OF BITING AND SUCKING INSECTS AFFECTING MAN AND ANIMALS By R. E. SNODGRASS Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, Agricultural Research Administration, U. S. Department of Agriculture CONTENTS Page Introduction 2 I. The cockroach. Order Orthoptera 3 The head and the organs of ingestion 4 General structure of the head and mouth parts 4 The labrum 7 The mandibles 8 The maxillae 10 The labium 13 The hypopharynx 14 The preoral food cavity 17 The mechanism of ingestion 18 The alimentary canal 19 II. The biting lice and booklice. Orders Mallophaga and Corrodentia. 21 III. The elephant louse 30 IV. The sucking lice. Order Anoplura 31 V. The flies. Order Diptera 36 Mosquitoes. Family Culicidae 37 Sand flies. Family Psychodidae 50 Biting midges. Family Heleidae 54 Black flies. Family Simuliidae 56 Net-winged midges. Family Blepharoceratidae 61 Horse flies. Family Tabanidae 61 Snipe flies. Family Rhagionidae 64 Robber flies. Family Asilidae 66 Special features of the Cyclorrhapha 68 Eye gnats. -

Evolution of the P53-MDM2 Pathway Emma Åberg1, Fulvio Saccoccia1, Manfred Grabherr1, Wai Ying Josefin Ore1, Per Jemth1* and Greta Hultqvist1,2*

Åberg et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:177 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-1023-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Evolution of the p53-MDM2 pathway Emma Åberg1, Fulvio Saccoccia1, Manfred Grabherr1, Wai Ying Josefin Ore1, Per Jemth1* and Greta Hultqvist1,2* Abstract Background: The p53 signalling pathway, which controls cell fate, has been extensively studied due to its prominent role in tumor development. The pathway includes the tumor supressor protein p53, its vertebrate paralogs p63 and p73, and their negative regulators MDM2 and MDM4. The p53/p63/p73-MDM system is ancient and can be traced in all extant animal phyla. Despite this, correct phylogenetic trees including both vertebrate and invertebrate species of the p53/p63/p73 and MDM families have not been published. Results: Here, we have examined the evolution of the p53/p63/p73 protein family with particular focus on the p53/ p63/p73 transactivation domain (TAD) and its co-evolution with the p53/p63/p73-binding domain (p53/p63/p73BD) of MDM2. We found that the TAD and p53/p63/p73BD share a strong evolutionary connection. If one of the domains of the protein is lost in a phylum, then it seems very likely to be followed by loss of function by the other domain as well, and due to the loss of function it is likely to eventually disappear. By focusing our phylogenetic analysis to p53/p63/ p73 and MDM proteins from phyla that retain the interaction domains TAD and p53/p63/p73BD, we built phylogenetic trees of p53/p63/p73 and MDM based on both vertebrate and invertebrate species.