Ahead by a Century: Tim Edgar, Machine-Learning, and the Future of Anti-Avoidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2013 Headlines of 2013 President’S Message

FOOD & BEVERAGE SPORT & RECREATION EVENTS & ENTERTAINMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2013 HEADLINES OF 2013 PRESIDENT’s MESSAGE SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE RIFE WITH CAN-CON. B5 A4 Sunday, April 21, 2013 Leader-Post • leaderpost.com Sunday, April 21, 2013 A5 More than 180 rigging points with HD over 4,535 kg of equipment overhead mobile Another Record Year Governance with 13 150 60 strobe light fixtures, 731 metres cameras speakers of lighting trusses, 720,000 watts in 14 of lighting power and 587 moving SOUND clusters head lighting fixtures The year 2013 will go down as In 2012, we finally made application to the Province of &VISION artsBREAKING NEWS& AT L EA D ERlifePOST.COM Canada’s annual music awards yet another record year for Evraz Saskatchewan to step away from our original (1907) Act. extravaganza — to be hosted at SECTION B TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 2013 Regina’s Brandt Centre tonight — requires a monumental effort in Place (operated by The Regina It has served us well for over a century, but had become planning and logistics. Here’s last year’s stage with some of the key numbers for this year’s event. Exhibition Association Limited): outdated for our current business activity and contemporary Design by Juris Graney 1,800 LED BRYAN SCHLOSSER/Sunday Post • Record revenues of $34.8M. governance model. In 2014, The Regina Exhibition panels Crews prepare the elaborate stage for the Juno Awards being held at the Brandt Centre tonight. on 13 suspended Setting the stage towers • Three extraordinary high Association Limited will continue under The Non-profit -

'69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking the Tragically Hip 3 Life Is

1 Summer of '69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking The Tragically Hip 3 Life Is A Highway Tom Cochrane 4 Takin' Care of Business Bachman Turner Overdrive 5 Tom Sawyer Rush 6 Working For The Weekend Loverboy 7 American Woman The Guess Who 8 Bobcaygeon The Tragically Hip 9 Roll On Down the Highway Bachman Turner Overdrive 10 Heart Of Gold Neil Young 11 Rock and Roll Duty Kim Mitchell 12 38 Years Old The Tragically Hip 13 New World Man Rush 14 Wheat Kings The Tragically Hip 15 The Weight The Band 16 These Eyes The Guess Who 17 Everything I Do (I Do IT For You) Bryan Adams 18 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 19 Run To You Bryan Adams 20 Tonight is a Wonderful Time to Fall in Love April Wine 21 Turn Me Loose Loverboy 22 Rock You Helix 23 We're Here For A Good Time Trooper 24 Ahead By A Century The Tragically Hip 25 Go For Soda Kim Mitchell 26 Whatcha gonna Do (When I'm Gone) Chilliwack 27 Closer To The Heart Rush 28 Sweet City Woman The Stampeders 29 Chicks ‘N Cars (And the Third World War) Colin James 30 Rockin' In The Free World Neil Young 31 Black Velvet Alannah Myles 32 Heaven Bryan Adams 33 Feel it Again Honeymoon Suite 34 You Could Have Been A Lady April Wine 35 Gimme Good Lovin' Helix 36 The Spirit Of Radio Rush 37 Sundown Gordon Lightfoot 38 This Beat Goes on/ Switchin' To Glide The Kings 39 Sunny Days Lighthouse 40 Courage The Tragically Hip 41 At the Hundreth Meridian The Tragically Hip 42 The Kid Is Hot Tonite Loverboy 43 Life is a Carnival The Band 44 Don't It Make You Feel The Headpins 45 Eyes Of A Stranger Payolas 46 Big League -

You Can't See Me I Am a Stranger…Do You Know What I Mean?

The Stranger I am a stranger…You can't see me I am a stranger…Do you know what I mean? I navigate the mud…I walk above the path Jumpin' to the right…Then I jump to the left On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path nobody knows And what I'm feelin'…Is anyone's guess What is in my head…And what's in my chest I'm not gonna stop…I'm just catching my breath They're not gonna stop…Please just let me catch my breath I am the stranger…You can't see me I am the stranger…Do you know what I mean? That is not my dad…My dad is not a wild man Doesn't even drink…My dad, he's not a wild man On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path that nobody knows I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… www.downiewenjack.ca Grace, too He said I'm fabulously rich C'mon just let's go She kinda bit her lip Geez, I don't know But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with will and determination And grace, too The secret rules of engagement Are hard to endorse When the appearance of conflict Meets the appearance of force But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with skill and it's frustration And grace, too www.downiewenjack.ca Poets Spring starts when a heartbeat's pounding When the birds can be heard Above the reckoning carts doing some final accounting Lava flowing in Superfarmer’s -

Song-Book.Pdf

1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rockin’ Tunes Ain’t No Mountain High Enough 6 Sherman The Worm 32 Alice The Camel 7 Silly Billy 32 Apples And Bananas 7 Swimming, Swimming 32 Baby Jaws 8 Swing On A Star 33 Bananas, Coconuts & Grapes 8 Take Me Out To The Ball Game 33 Bananas Unite 8 The Ants Go Marching 34 Black Socks 8 The Bare Necessities 35 Best Day Of My Life 9 The Bear Song 36 Boom Chicka Boom 10 The Boogaloo 36 Button Factory 11 The Cat Came Back 37 Can’t Buy Me Love 11 The Hockey Song 38 Day O 12 The Moose Song 39 Down By The Bay 12 The Twinkie Song 39 Don’t Stop Believing 13 The Walkin’ Song 39 Fight Song 14 There’s A Hole In My Bucket 40 Firework 15 Three Bears 41 Forty Years On An Iceberg 16 Three Little Kittens 41 Green Grass Grows All Around 16 Through The Woods 42 Hakuna Matata 17 Tomorrow 43 Here Little Fishy 18 When The Red, Red Robin 43 Herman The Worm 18 Yeah Toast! 44 Humpty Dump 19 I Want It That Way 19 If I Had A Hammer 20 Campfire Classics If You Want To Be A Penguin 20 Is Everybody Happy? 21 A Whole New World 46 J. J. Jingleheimer Schmidt 21 Ahead By A Century 47 Joy To The World 21 Better Together 48 La Bamba/Twist And Shout 22 Blackbird 49 Let It Go 23 Blowin’ In The Wind 50 Mama Don’t Allow 24 Brown Eyed Girl 51 M.I.L.K. -

Download the 2019 JCSH Annual Report in English

Table of Contents Message from the Executive Director ........................................................... ii Executive Summary ............................................................................... iii JCSH Statement on Reconciliation ........................................................... vi Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 The Case for Cross-Sector Collaboration ....................................................... 3 About JCSH ....................................................................................... 3 Mandate ........................................................................................ 3 Vision ........................................................................................... 3 Mission .......................................................................................... 3 Strategic Direction ............................................................................ 3 Long-Term Outcomes......................................................................... 4 Organizational Structure ..................................................................... 5 About Comprehensive School Health ........................................................... 6 Consortium Accomplishments .................................................................... 8 Leadership ..................................................................................... 8 Knowledge Development & Exchange................................................... -

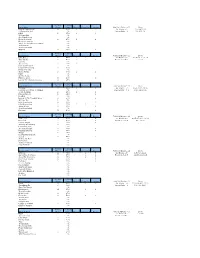

Up to Here # Times Played % Shows Played Opened Closed Set Encore

# Times % Shows Up To Here Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Blow at High Dough 9 60% 2 3 Set Blocks = 6 1,5,7,9,12,14 I'll Believe In You 0% Encore Sets = 5 2,6,8,11,15 NOIS 10 67% 1 4 38 Years Old 0% She Didn't Know 0% Boots Or Hearts 10 67% 2 4 Everytime You Go 0% When The Weight Comes Down 0% Trickle Down 0% Another Midnight 0% Opiated 8 53% 1 2 # Times % Shows Road Apples Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Little Bones 8 53% 1 1 Set Blocks = 8 1,2,4,6,8,10,12,15 Twist My Arm 8 53% 1 2 1 Encore Sets = 3 3,9,13 Cordelia 0% The Luxury 5 33% 1 Born In The Water 0% Long Time Running 4 27% Bring It All Back 0% Three Pistols 6 40% 1 1 Fight 0% On The Verge 0% Fiddler's Green 6 40% 3 Last Of The Unplucked Gems 4 27% # Times % Shows Fully Completely Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Courage 10 67% 2 4 Set Blocks = 7 3,5,8,10,11,13,15 Looking For A Place To Happen 0% Encore Sets = 6.1 1,2,4,7,9,14,15 100th Meridian 10 67% 2 3 Pigeon Camera 2 13% 1 Lionized 0% Locked In The Trunk Of A Car 3 20% 2 We'll Go Too 1 7% Fully Completely 4 27% 3 Fifty Mission Cap 5 33% 1 1 Wheat Kings 8 53% 4 The Wherewithal 0% Eldorado 3 20% 1 # Times % Shows Day For Night Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Grace, Too 13 87% 1 4 Set Blocks = 9 2,3,5,6,7,9,11,13,14 Daredevil 7 47% 1 Encore Sets = 4 4,10,12,15 Greasy Jungle 5 33% 1 Yawning Or Snarling 2 13% Fire In The Hole 0% So Hard Done By 7 47% 1 Nautical Disaster 4 27% 2 Thugs 2 13% Inevitability Of Death 0% Scared 7 47% 2 An Inch An Hour 0% Emergency 0% Titanic Terrarium 0% Impossibilium 0% # Times % Shows Trouble At The Henhouse Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Giftshop 11 73% 1 5 Set Blocks = 6 3,5,7,10,12,14 Springtime In Vienna 7 47% 1 1 Encore Sets = 7 1,4,6,8,11,13,15 Ahead By A Century 13 87% 2 7 Don't Wake Daddy 4 27% 1 Flamenco 5 33% 2 700 Ft. -

Voting with Their Feet Unable to Push out Their Socialist Dictator in a Free Election, Hungry Venezuelans Escape to Colombia

POT SHOTS: MARIJUANA IN BEER, ICED TEA, JUICE … AUGUST 18, 2018 Voting with their feet Unable to push out their socialist dictator in a free election, hungry Venezuelans escape to Colombia SPYING: THE EVANGELICAL CONNECTION TRENDING: PETERSON, PRAGER, AND SHAPIRO A Biblical, non-insurance approach to health care Monthly costs: As believers in Christ, we are called to glorify God in all that we do. (Ranges based on age, household size, and membership level) Samaritan members bear each other’s burdens by sharing the cost of medical bills while praying for and encouraging one another. Members Individuals $100-$220 can choose between two membership options for sharing their medical 2 Person $200-$440 needs: Samaritan Classic and Samaritan Basic. 3+ People $250-$495 As of July 2018 Find more information at: samaritanministries.org CONTENTS | August 18, 2018 • Volume 33 • Number 15 32 38 44 48 63 FEATURES DISPATCHES 32 7 News Analysis / Human Race / The other border crisis Quotables / Quick Takes At the border with Colombia, hungry Venezuelans seek out supplies to survive their country’s harrowing economic collapse— while Christians try their best to help CULTURE 19 Movies & TV / Books / Children’s Books / Q&A / Music 38 Pot in the bottle Big Alcohol is adding a new ingredient—marijuana—to its moneymaking brew NOTEBOOK 55 Lifestyle / Technology / 44 Bad connections? Medicine / Politics A Russian spy drama entangles the National Prayer Breakfast, revealing both weaknesses and strengths of the prayer VOICES breakfast movement 4 Joel Belz 48 16 Janie B. Cheaney Digital sages Mindy Belz Public intellectuals Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, and Dennis 30 Prager are speaking powerfully to a young generation trying 61 Mailbag to find its bearings 63 Andrée Seu Peterson 64 Marvin Olasky ON THE COVER: Venezuelan citizens cross the Simón Bolívar International Bridge to Colombia in Cúcuta, Colombia. -

Gord Downie: Ahead by a Century

Gord Downie: Ahead by a Century Gord Downie, musician, singer, songwriter, environmentalist and native rights activist, left his mark on generations of Canadians. His lyrics for The Tragically Hip, quirky and clever as they are, have become a part of the Canadian soundtrack. Songs such as Blow at High Dough , Courage , Wheat Kings and Bobcaygeon , are now sung at campfires and hockey games, but also analyzed for PhD papers. Their songs explored Canadian geography and history, the themes of the water and the land, creating a sense of pride of place, but also referenced Canadian authors (Hugh MacLennan, for one) and the work of William Shakespeare. Taking pride in their Canadian roots (at a time when it was not cool in music), touring the nation relentlessly in the early days, and consistently evolving, over 13 studio albums and through four decades, the Hip maintained a distinct sound and a strong position in the hearts of English Canada. In the wake of an untreatable brain cancer diagnosis in 2016, Downey chose to go on the road with the Hip, to engage with fans, to conduct a national celebration. Fans raised money for cancer charities. The Tragically Hip’s final concert, held in their hometown of Kingston, ON, on August 20, 2016, was broadcast nationally and viewed in parks across Canada, hitting record viewer numbers of over 11 million. Downie chose to use his final days to highlight causes close to his heart. Secret Path: The Story of Chanie Wenjack , highlighted the legacy of the residential school system and its impact on First Nations. -

Tom Mcgill @ Starstruck (716)896-6666 Toast Songlist

FOR BOOKING INFO, CALL; TOM MCGILL @ STARSTRUCK (716)896-6666 TOAST SONGLIST All Because Of You – U2 One – U2 Vertigo/I Will Follow – U2 American Girl – Tom Petty Little Miss Can’t Be Wrong – Spin Doctors Two Princes – Spin Doctors Dani California – Red Hot Chili Peppers Flagpole Sitta’ – Harvey Danger You’re all I have - Snow Patrol Clumsy – Our Lady Peace High & Dry – Radiohead Creep - Radiohead Inside Out – Eve 6 Alternative Girlfriend – Barenaked Ladies Brian Wilson – Barenaked Ladies What A Good Boy – Barenaked Ladies Million Dollars – Barenaked Ladies Hey Jealousy – Gin Blossoms T-N-T – AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie - AC/DC Dirty Deeds – AC/DC What Is, And What Should Never Be – Led Zeppelin Ramble On - Led Zeppelin Little Bones – Tragically Hip New Orleans Is Sinking – Tragically Hip Ahead By A Century – Tragically Hip Poets - Tragically Hip Nautical Disaster – Tragically Hip Twist My Arm – Tragically Hip Grace, Too – Tragically Hip Courage – Tragically Hip Blow at High Dough - Tragically Hip I’ll Be Leaving You – Tragically Hip Better Man – Pearl Jam Evenflow – Pearl Jam Daughter – Pearl Jam Interstate Love Song – Stone Temple Pilots Santeria - Sublime What I Got - Sublime Long Road to Ruin – Foo Fighters Roxanne – The Police One Way Out – Allman Brothers Pride & Joy – Stevie Ray Vaughn Cold Shot – Stevie Ray Vaughn Ants Marching – Dave Matthews Band Blister in Sun – Violent Femmes Laid – James FOR BOOKING INFO, CALL; TOM MCGILL @ STARSTRUCK (716)896-6666 Remedy – The Black Crowes Hard to Handle – The Black Crowes La Grange – ZZ Top -

1 Summer of '69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking the Tragically Hip 3 Life Is a Highway Tom Cochrane 4 Takin' Care of Busine

1 Summer of '69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking The Tragically Hip 3 Life Is A Highway Tom Cochrane 4 Takin' Care of Business Bachman Turner Overdrive 5 Tom Sawyer Rush 6 Working For The Weekend Loverboy 7 American Woman The Guess Who 8 Bobcaygeon The Tragically Hip 9 Sunglasses At Night Corey Hart 10 Heart Of Gold Neil Young 11 If I Had A Million Dollars Barenaked Ladies 12 Try Blue Rodeo 13 The Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgderald Gordon Lightfoot 14 Wheat Kings The Tragically Hip 15 The Weight The Band 16 These Eyes The Guess Who 17 Everything I Do (I Do IT For You) Bryan Adams 18 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 19 Run To You Bryan Adams 20 Never Surrender Corey Hart 21 Turn Me Loose Loverboy 22 You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette 23 We're Here For A Good Time Trooper 24 Ahead By A Century The Tragically Hip 25 Go For Soda Kim Mitchell 26 Hallelujah Leonard Cohen 27 Closer To The Heart Rush 28 Sweet City Woman The Stampeders 29 If You Could Read My Mind Gordon Lightfoot 30 Rockin' In The Free World Neil Young 31 Black Velvet Alannah Myles 32 Heaven Bryan Adams 33 One Week Barenaked Ladies 34 You Could Have Been A Lady April Wine 35 The Safety Dance Men Without Hats 36 The Spirit Of Radio Rush 37 Sundown Gordon Lightfoot 38 This Beat Goes on/ Switchin' To Glide The Kings 39 Sunny Days Lighthouse 40 Courage The Tragically Hip 41 Home For A Rest Spirit Of The West 42 The Kid Is Hot Tonite Loverboy 43 Nova Heart The Spoons 44 5 Days In May Blue Rodeo 45 Eyes Of A Stranger Payolas 46 Big League Tom Cochrane 47 Brian Wilson Barenaked Ladies 48 -

INVITED to the FEAST?: PROBLEMS of HOSPITALITY, COLONIALITY and IDENTITY in the MUSIC CLASSROOM. ELEANOR M. JOHNSTON a Dissertat

INVITED TO THE FEAST?: PROBLEMS OF HOSPITALITY, COLONIALITY AND IDENTITY IN THE MUSIC CLASSROOM. ELEANOR M. JOHNSTON A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Education York University Toronto, Ontario July 2020 © Eleanor M. Johnston, 2020 i Abstract This study sought to understand the complicated interactions of student, teacher, curriculum and curricular objects in one junior music classroom in Ontario. This work was taken up under Derrida’s call for cities of refuge in On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness while mindful of the ways in which colonial structures can appear cosmopolitan, as in the trope of music as universal language. It explored how changing the music that was studied might affect their perception of their own and others’ belonging in the music room. This in turn, asks us to consider how curricular choices affect behavior, engagement and success in our students. Through ethnographically informed methods including interviews and observations, surveys and a curricular intervention using global pop music, student and teacher attitudes and engagement with diverse musics and cultures were examined. Three major themes emerged in the analysis; complex and conflicted identities in students who believed much of their tastes and selves did not belong at school, a rapid fluidity in musical taste, and the omnipresent shadow of a Western cultural framework of music curriculum, academic success, and schooling behavior and expectations. Several pedagogical and curricular implications were explored, including engaging students through academic approaches to music, student belonging and hospitality practices, and the difficulties of reception of multicultural approaches within the school. -

The Hip Rock out at "Secret" Show 8/10/09 3:54 PM

The Hip Rock Out At "Secret" Show 8/10/09 3:54 PM Chart Magazine The Hip Rock Out At "Secret" Show Thursday February 21, 2002 @ 05:30 PM By: ChartAttack.com Staff May 2002 issue featuring Moby (Check out his centerspread Lee's Palace Wallpaper Download Toronto, Ontario ), February 20, 2002 Sum 41, Hanson by Jim Kelly Brothers & more. Online ordering for this and other Wednesday night, when the Canadian issues now Olympic men’s hockey team was set to available. play a must-win game against Team Finland, nationalistic fervour was running high inside Lee’s Palace in Toronto. But The Happy Hip Hockey Night. that was only partly because of the impending hockey showdown. The 500-capacity club was filled with fans who had come to see Canada’s favourite band, The Tragically Hip, in a rare club show — a surprise charity concert that had been announced only that day at noon, prompting diehard fans to line up for hours in the rain until the doors opened at 5 p.m. All proceeds from the show (everyone paid $25 at the door) went to the Special Olympics. Ostensibly, it was also a warm-up gig for the band’s February 23 concert in Salt Lake City, where they’ll be performing for Canada’s Olympic athletes and contest-winners. The feeling inside the club was that of a near-perfect confluence of Canadian cultural expressions. We celebrate the Canadian-ness of The Tragically Hip in much the same way that we cling to the game of hockey as a touchstone of our way of life.