Marine Tourism and Sharks: a Case Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Engineers Journal

---------.---- The Royal Engineers , I' * .ii ; Journal. H'lii I '' ) Sir Charles Pasley (IV) . Lieut.-Colonel P. ealy 569 1 Mechanization and Divisional Engineers. Part m. f' Brevet Lieut.-Colonel N. T. Fitzratrick 691 A Subaltern in the Indian Mutiny. Part VI. Brevet Colonel C. B. Thackeray 597 Repairs to the Barge Pier at Shoeburyness . Brevet Major A. Winnis 611 i Further Notes on the Roorkee Pattern Steel Crib Lieut.-Colonel G. Le Q. Martel 687 The Principles of Combined Operations . Brigadier W. G. S. Dobbie 640 The Transatlantic Venture . Captain W. G. Fryer 656 Further Experiments in Vibro-Concrete Piling in the North-West Frontier Province Colonel C. H. Haswell 677 The Principles and Practice of Lubrication as Applied to Motor Vehicles Captain S. G. Galpin 685 Two Sapper Subalterns in Tibet . Lieutenant L. T. Grove 690 Bridging on the Chitral Road, with Special Reference to the N.W.R. Portable Type Steel Bridge . Lieutenant W. F. Anderson 702 Report on Concealment from the Air . Major B. C. Dening 706 An "F" Project . Lieutenant A. E. M. Walter 711 A Mining 8tory . V. 715 Memoirs. Books. Magazines. Correspondence . 716 VOL. XLV. DECEMBER, 1931. CHATHAM: THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS. TELEPHONE: CHATHAM, 2669. AGENTS AND PRINTERS: MACKAYS LTD. LONDON: 171 HUGH RZES. LTD.. 5. REGENT STREET. S.W.I. ..... m; 11-. 4 J"b !" All ,:,i INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE , v.= L-. - ·--·11-1 EXPAMET EXPANDED METAL Specialities "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEET i REINFORCEMENT FOR I CONCRETE. "EXPAMET" and "BB" LATHINGS FOR PLASTERWORK. "EXMET" REINFORCEMENT FOR BRICKWORK. "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEETS, for Fencing, Openwork Partitions, Machinery Guards, Switchboard Enclosures, Etc. -

A Study of the Soul in Recent Poetics

ROSE OF T!jE WORLD A STUDY OF THE SOUL IN A RECENT POETICS Jchn William Scoggan B.Sc. Carleton University, Ottawa, 1968 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of E.nglish @ JOHN WILLIAM SCOGGAN 1973 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July, 1973 VOLUME I APPROVAL Name : John Scoggan Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Charles Olson's Imago Mundi Eramini ng Committee: Chairman: Dr. S .A. Black ~ar~hMaud Senior Supervisor Robin Blaser Evan Alderson Arthur Stone Assistant Professor Department of Mathematics Simon Fraser University Date Approved: July 25, 1972 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE f hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behaif or for cne nf its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of ~hesis /~issertation : Rose of the World: a study of the soul in a recent poetics Author- : John William Scoggan (name ) December 11, 1973 ABSTRACT This thesis is about the Gold Flower which has always stood for the sources of the human soul. -

Unep Kannet 2009

International Environmental Law-making and Diplomacy Review 2008 Ed Couzens and Tuula Honkonen (editors) UNIVERSITY OF JOENSUU – UNEP COURSE SERIES 8 University of Joensuu Joensuu, Finland, 2009 i University of Joensuu – UNEP Course Series 8 Publisher University of Joensuu Department of Law P.O.Box 111, FIN-80101 JOENSUU, FINLAND Editors Ed Couzens and Tuula Honkonen Editorial Marko Berglund, Michael Kidd, Tuomas Kuokkanen, Board Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, Akpezi Ogbuigwe, Barbara Ruis Contact Joensuu University Library/Sales of Publications P.O. Box 107, FIN-80101 JOENSUU, FINLAND Tel.: +358 13 251 2652, +358 13 251 4509 Fax: +358 13 251 2691 E-mail: [email protected] Website: <http://www.joensuu.fi/library> United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Division of Environmental Policy Implementation (DEPI) P.O. Box 30552, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya E-mail: [email protected] Website: <http://www.unep.org/training> Exchanges Joensuu University Library/Exchanges P.O. Box 107, FIN-80101 JOENSUU, FINLAND Tel.: +358 13 251 2677 Fax: +358 13 251 2691 E-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1795-6706 ISBN 978-952-219-254-7 Cover Leea Wasenius Design Layout Saarijärven Offset Oy Saarijärven Offset Oy Saarijärvi, Finland 2009 ii Contents Foreword......................................................................................................... vi Preface............................................................................................................. vii Part I General Issues of International Environmental Law-making and Governance in Respect of Oceans -

A Historical Overview of the Origins of Anti-Shark Measures in Natal, 1940 - 1980

A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE ORIGINS OF ANTI-SHARK MEASURES IN NATAL, 1940 - 1980 Melissa Joyce van Oordt A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College 2006 I declare that this thesis has not been submitted to any other university and that it is my entirely own work and that I have given due acknowledgement of all sources. Melissa Joyce van Oordt Supervisor Copyright by Melissa Joyce van Oordt 2006 © Table of Contents Abstract III Acknowledgments iv - vi Figures and Illustrations vii Abbreviations viii Prologue The emergence of beach recreation and anti-shark measures in Natal: 1900s - 1957 "Caution"l 1 - 16 Chapter One "Black December", Myths, Fear and Sharks "Undoubtedly it is a man-killer.,,2 17 - 48 Chapter Two Post-War Beach Recreation off the Natal coastline and the establishment of shark research institutions in Natal I Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository (PAR), Attorney General's Office (AGO) 1/8/47, 45A11895, 'Natal Water Police Point to The Attorney General: Superintendent of Water Police Reports on Danger of Sharks in Durban', 6th February 1895. 2 V. Coppleson. Shark Attack (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1988) originally published in 1958, p.2 on "Great Wh ites" 49 - 81 Chapter Three Anti-shark measures in Natal during the 1960s 82 -108 Chapter Four The 1970s, Anti-shark measures, Tourism, Media and Conservation 109 - 141 Conclusion 142 - 151 Bibliography 152 - 182 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the ongms of anti-shark measures in Natal, highlighting the relationship between beach recreation, anti-shark measures and the important influence of human perceptions of sharks. -

The Reference Book of Information and Statistics Relating to the Territory of Hawaii

The Reference Book of Information and Statistics Relating to the Territory of Hawaii THE PRINTSHOP COMPANY, LTD. Compiler and Publisher FIFTY-NINTH ISSUE HONOtULU, HAWAII 1932 I 'PRICE $1.00 PRINTED IN U. S. A. MAIL $1.15 BI~HOP TRIJ~T £0.~ lTD. REAL ESTATE TRUSTS INVESTMENTS PROPERTY MANAGEMENT STOCKS AND BONDS LARGEST SAFE DEPOSIT VAULTS IN HAWAII • You Are Cordially Invited to Consult Our Trust Officers Il This comfortable Observation Coach leaves t.he Oahu Railway Station daily at 9:15 A. M., and takes you by the wonderful scenic rail route, to Haleiwa, where you arrive at 11:45 A. l\L EIGHTY-NINE MILES OF SIGHTSEEING DE LUXE DAILY $2.45 See Oahu by Rail and Bus This luxurious Bus leaves Haleiwa daily at 12:45 P. 1\L, and takes you via Schofield Barracks and Kamehameha Highway, to the Young Hotel, in Honolulu, where you arrive at 2:30 P. l\L OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS \V. 11. ALEXANDER.................................. Chairman of the Board ]. \VATERHOUSE. ....................... President and General Manager H. A. BALDWIN ............................................................ Vice-President C. R. HEMEN\VA Y .... Vice-President and Asst. Gen. Manager ]. P. COOKE.... ----·------------------------------------------------------------·····-···Treasurer R. E. MIST----------------------------------------------------------------------------------Secretary ]. \V. SPEYER ______________________________________________________________ Asst. Treasurer ]. F. 1f ORGAN ····----------------------------------------------------------Asst. Treasurer -

Individual Shark Profiling: an Innovative and Environmentally

Received: 11 May 2018 Accepted: 24 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/conl.12612 POLICY PERSPECTIVE Individual shark profiling: An innovative and environmentally responsible approach for selectively managing human fatalities Eric E. G. Clua1,2 John D. C. Linnell3 1 EPHE, PSL Research University, Perpignan, Abstract France Most shark-induced human fatalities are followed by widespread and unselective 2Labex Corail, CRIOBE, Moorea, French Polynesia culling campaigns that have limited effectiveness and may have high ecological costs 3Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, for threatened species. The blanket culling strategy implicitly assumes that incident Trondheim, Norway risk is directly correlated with shark density, an assumption that has yet to be demon- Correspondence strated. We present the alternative hypothesis that incidents are more likely to be Eric E. G. Clua, EPHE, PSL Research Univer- sity, CRIOBE USR3278 EPHE-CNRS-UPVD, caused by behavioral variability among individual sharks than due to shark density. F-66860 Perpignan, France. Throughout their ontogenetic development, large species of sharks opportunistically Email: [email protected] establish a diet that is rarely, if ever, inclusive of humans as a food source. We pro- ORCID: D-7820-2013 pose that, some animals with specific behaviors (including boldness) may potentially Editor Matt W.Hayward pose a higher risk than conspecifics. Under this scenario, the risk of a shark attack in a given area would relate to the presence of a limited number of high-risk individuals rather than shark density. In terms of management of human fatalities, such a hypothesis would favor aban- doning general culling campaigns and replacing them with approaches that profile and selectively remove the potential problem individuals, as is done in the terrestrial realm when managing predators that attack humans or livestock. -

Highlights August 2012

If you do not currently receive our monthly highlights and would like to, please email: [email protected] Click here for press office contacts Click on logo to go directly to channel Highlights August 2012 This brand new eight part series from the makers of Deadliest Catch follows the treasure Gold Divers hunters that flock to the coasts of Alaska to dive for the ultimate prize, gold. Teams of two battle UK PREMIERE SERIES it out on homemade custom built rigs, trying TUESDAYS FROM 14TH AUGUST, 10.00PM to stay alive while they dive in the deathly cold water. How will they survive when they take on the ferocious conditions of the Arctic Ocean? This new series profiles the eccentric characters who battle the extreme climate, life threatening hazards and each other in a relentless hunt for gold. From an Alaskan social worker who sinks his life savings into a lifelong dream, to the only female dredger in Nome, these rugged treasure hunters put it all on the line to scour the sea floor for sparkling, precious metal. CONTACT [email protected] Everyone’s favourite programming event Shark Shark Week continues with Killer Shark the Week has moved over to Animal Planet this Attacks of Black December (Sunday 19th, Shark Week year and promises to be back with an even 9.00pm) the story of a Summer in South Africa bigger bite than before. in 1957 when the balance of nature was tipped UK PREMIERES with a spate of shark attacks that devastated a MONDAY 13TH - SUNDAY 19TH AUGUST First up is the hour long special Great White community. -

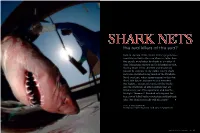

The Real Killers of the Sea?

SHARK NETS the real killers of the sea? Back in the late 1950s, South Africa’s popular east coast was rocked to the core when no fewer than five people were bitten by sharks in a matter of days. Mass panic ensued and holidaymakers fled, leaving resort towns deserted and financially ruined. In response to the public outcry, shark nets were installed along much of the KwaZulu- Natal coastline, where many remain to this day. Shark bite figures plummeted and everyone was happy… except, of course, for the sharks and the multitude of other animals that are killed every year. Photojournalist and marine biologist Thomas P. Peschak investigated the true cost of lethal bather-protection methods and asks, ‘Are shark nets really still necessary?’ TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHS THOMAS P. PESCHAK/SAVE OUR SEAS FOUNDATION WWW.AFRICAGEOGRAPHIC.COM 39 40 AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC • MAY 2009 THIS SPREAD Populations of great ham- merhead sharks are declining worldwide and South Africa is no exception. Shark nets have been recording fewer catches of the species, which suggests a reduc- tion in their numbers. PREVIOUS SPREAD Unlike many ocean-users, surfers are generally well educated about sharks and the minimal risks they pose. In this photograph, shark-diving expert Mark Addison of BlueWilderness tests the reaction of a blacktip to a surfboard. PAGE 38 Despite enjoying protected status in South Africa since 1991, great white sharks continue to be caught legally in the shark nets under an exemption. WWW.AFRICAGEOGRAPHIC.COM 43 was also bitten by a shark while stand- ing on a shallow sandbank, and suc- THEY [THE SHARK NETS] ACT AS cumbed to his injuries. -

Why Marine Protected Areas Are Important

Bulletin NEWS Thursday November 6 2014 7 No longer plenty of fish in the sea over-exploited. 800 000 tons of In the “Black December” of 1958, five bathers were killed by sharks along marine life are the Kwa-Zulu Natal coastline. Shark nets were introduced, a major contrib- harvested utor to bi-catch of dolphins, turtles with many years of killing top predators. make changes. annually “Shark nets were never set up to save Sewerage spills, plastic pollution, people but to safeguard tourism,” said and aquaculture are other major KAREN WATKINS Professor Attwood. threats to the integrity of the ocean The better option would be a mag- habitat. any years ago fishermen netic field and for the Natal Parks Professor Attwood feels the answer threw bait overboard in Board to be transparent regarding the to dwindling fish stocks is an increase MFalse Bay and the water costs to the environment and the aim in the number of MPAs. At present was filled with fish. Nowadays, for the nets. they cover 19% of our coastline, with Boulders penguins have to swim In 1964, the first MPA was declared, the west coast being mostly neglected. further out to sea in search of Tsitsikamma, with many to follow in He said only nine percent of the food. And it’s not only penguins the next four decades. But their real coast falls within no-take zones, where who are finding fish a rare com- value was only articulated in 1989. nothing is to be removed by fishing or modity. Quotas came in 1978; the line fish- other methods. -

Chapter One: Black December, Myths, Fear and Sharks ‘The Sea Along the Natal Coast Is Subject to Increasing Pressures from Man’S Activities’ 1

PLEASE NOTE THIS IS A DRAFT IN PROGRESS DO NOT CITE Chapter One: Black December, Myths, Fear and Sharks ‘The sea along the Natal coast is subject to increasing pressures from man’s activities’ 1 Melissa van Oordt Masters Student Howard College Campus, Durban, University of KwaZulu-Natal ‘For God’s sake, HELP me’2 Black December: December 1957 – April 1958: On 30th December 1957: …moments before the attack a shark patrol plane passed overhead. The shark went straight for the victims [sic] buttocks and wheeled for a second attack when Mr. Brokensha grabbed the shark’s tail. The animal threw him off and returned to attack…the shark severed the victim’s left arm and then swam off.3 Black December was described by the Natal Mercury (1958) as an: unprecedented reign of terror which virtually put an end to sea-bathing along the South Coast and sent thousands of visitors streaming to net- protected beaches, the marauding sharks have cast a shadow of death over Southern Africa’s premier holiday playground…4 1 G Cliff and RB Wilson Natal Sharks Board’s field guide to Sharks and other marine animals Paper Print, Westmead, Pinetown 1994 p 3 2 The last words record from 5th shark attack victim: “Killer Shark was furthest inshore yet” The Natal Mercury Durban, Friday, January 10, 1958 p 1 3 Natal Shark Board Archives (NSBA) South African Shark Attack File (SASA): KwaZulu-Natal (KZN): File N57/4: File: Julia Painting 30 December 1957 (Shark Attack File managed by Geremy Cliff) 4 “South Coast Shark Attacks Now Total Five” The Natal Mercury Durban, Friday, January 10, 1958 p 2 1 PLEASE NOTE THIS IS A DRAFT IN PROGRESS DO NOT CITE In December 1957, the Natal5 South coast had seen four shark attacks:6 Between January and April 1958 a further three attacks occurred along the South coast of Natal. -

Thesis Sci 2020 Sheridan Katherine

Human Safety and Shark Conservation: An Analysis of Surfer Risk Perceptions and Attitudes towards Shark Management Katherine Sheridan 10th February 2020 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology by coursework and dissertation Supervisors: Professor Justin O’Riain, Professor Mark Needham Universityand Professor of Nicoli Cape Nattrass Town Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa, Department of Biological Sciences University of Cape Town Rondebosch, 7701 South AfricaEmail: [email protected] i The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Plagiarism Declaration 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is using another’s work and to pretend that it is one’s own. 2. I have used the Conservation Biology Journal format as the convention for citation and referencing. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this project from the work, or works of other people has been attributed, cited and referenced. 3. This project is my own work. I have not allowed, and will not allow, anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. 4. I acknowledge that copying someone else’s assignment or essay, or part of it, is wrong, and declare that this is my own work.