Swing Shift Cinderella and Te Screwy Truant - 1945), Both to Create a Comic Efect and to Oppose the Former Code of Representation to the New One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Fraternite! Eqalite!

VOL. 119 - NO. 3 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, JANUARY 16, 2015 $.35 A COPY Liberte! Fraternite! Eqalite! by Sal Giarratani This past Saturday, a large How can we defeat an en- crowd gathered on the emy if we won’t even prop- Boston Common standing in erly identify who that enemy solidarity with millions of is? Even the new Presi- people in Paris’ Place de la dent of Egypt Abdel-Fattah Republique against Radical el-Sissi has courageously Islamic acts of terror that spoken for the need for a killed 17 people last week. Revolution in Islam and for Some 40 world leaders countering those who mis- joined arms together in sup- use the religion of Muslims. port of France and against On second thought, per- those seeking civilization haps Obama didn’t belong jihad. in that recent gathering in Many marched together in Paris since the world needed support of those values of to see leaders linking arms modern civilization under with one another. attack today. It was a march We insulted not only for liberty. It was a march for the French of 2015, we in- all of us. It was also a march sulted the bond between against those using reli- our nations built up since gious fanaticism and killing the days of the American innocents in the name of White House, it was a dumb send Vice President Joe was a deliberate move not to Revolution. their God. mistake that America went Biden or Secretary of State link the United States of We must not be afraid to Why wasn’t President AWOL at this world-wide John F. -

American WWII Propaganda Cartoons

Name _____________________________________ Date ________________________ Period ______ American WWII Propaganda Cartoons “Blitz Wolf” – A cartoon produced in 1942 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Short Subject Cartoon. The plot is a parody of the Three Little Pigs, told from a WWII anti-German propaganda perspective. As you watch the cartoon, answer the following questions: Who do the Three Little Pigs represent? Who does the Wolf represent? What does this cartoon say about America’s view of Germany and Hitler? “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap” - A 1942 one-reel animated cartoon short subject released by Paramount Pictures. It is one of the best-known World War II propaganda cartoons. The cartoon gets its title from a novelty song written by James Cavanaugh, John Redmond and Nat Simon. As you watch the cartoon, answer the following questions: Who does Popeye represent? How are the Japanese portrayed? What does this cartoon say about America’s view of Japan and its people? Using complete sentences, answer the following questions about the use of animated cartoons for anti- war propaganda. 1. Is the use of animation and humor appropriate for depicting the serious nature of war? Use at least 2 specific examples to explain your opinion. 2. The U.S. has been fighting the War on Terror for over a decade. If such propaganda cartoons were made today featuring Iraqis, Afghans, or others targeted in the War on Terror, would they be accepted? Would they be considered offensive? Use at least 2 specific examples to explain your opinion. -

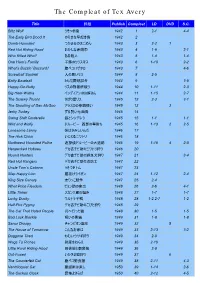

The Compleat of Tex Avery

The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. Blitz Wolf うそつき狼 1942 1 2-1 4-4 The Early Bird Dood It のろまな早起き鳥 1942 2 Dumb-Hounded つかまるのはごめん 1943 3 2-2 1 Red Hot Riding Hood おかしな赤頭巾 1943 4 1-9 2-1 Who Killed Who? ある殺人 1943 5 1-4 1-4 One Ham’s Family 子豚のクリスマス 1943 6 1-10 2-2 What’s Buzzin’ Buzzard? 腹ペコハゲタカ 1943 7 4-6 Screwball Squirrel 人の悪いリス 1944 8 2-5 Batty Baseball とんだ野球試合 1944 9 3-5 Happy-Go-Nutty リスの刑務所破り 1944 10 1-11 2-3 Big Heel-Watha インディアンのお婿さん 1944 11 1-15 2-7 The Screwy Truant さぼり屋リス 1945 12 2-3 3-1 The Shooting of Dan McGoo アラスカの拳銃使い 1945 13 3 Jerky Turkey ずる賢い七面鳥 1945 14 Swing Shift Cinderella 狼とシンデレラ 1945 15 1-1 1-1 Wild and Wolfy ドルーピー 西部の早射ち 1945 16 1-13 2 2-5 Lonesome Lenny 僕はさみしいんだ 1946 17 The Hick Chick いじわるニワトリ 1946 18 Northwest Hounded Police 迷探偵ドルーピーの大追跡 1946 19 1-16 4 2-8 Henpecked Hoboes デカ吉チビ助のニワトリ狩り 1946 20 Hound Hunters デカ吉チビ助の野良犬狩り 1947 21 3-4 Red Hot Rangers デカ吉チビ助の消防士 1947 22 Uncle Tom’s Cabana うそつきトム 1947 23 Slap Happy Lion 腰抜けライオン 1947 24 1-12 2-4 King Size Canary 太りっこ競争 1947 25 2-4 What Price Fleadom ピョン助の家出 1948 26 2-6 4-1 Little Tinker スカンク君の悩み 1948 27 1-7 1-7 Lucky Ducky ウルトラ子鴨 1948 28 1-2 2-7 1-2 Half-Pint Pygmy デカ吉チビ助のこびと狩り 1948 29 The Cat That Hated People 月へ行った猫 1948 30 1-5 1-5 Bad Luck Blackie 呪いの黒猫 1949 31 1-8 1-8 Senor Droopy チャンピオン誕生 1949 32 5 The House of Tomorrow こんなお家は 1949 33 2-13 3-2 Doggone Tired ねむいウサギ狩り 1949 34 2-9 Wags To Riches 財産をねらえ 1949 35 2-10 Little Rural Riding Hood 田舎狼と都会狼 1949 36 2-8 Out-Foxed いかさま狐狩り 1949 37 6 The Counterfeit Cat 腹ペコ野良猫 1949 38 2-11 4-3 Ventriloquist Cat 腹話術は楽し 1950 39 1-14 2-6 The Cuckoo Clock 恐怖よさらば 1950 40 2-12 4-5 The Compleat of Tex Avery Title 邦題 Publish Compleat LD DVD S.C. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

Cartoons— Not Just for Kids

Cartoons— Not just for kids. Part I 1. Chuck Jones later named this previously unnamed frog what? 2. In the 1990s the frog became the mascot for which television network? 3. What was Elmer Fudd’s original name? 4. What is the name of the opera that “Kill the Wabbit” came from? 5. Name a Looney Tunes animal cartoon character that wears pants: 6. What is the name of Pepe le Pew’s Girlfriend? 7. Name 3 Looney Tune Characters with speech impediments 8. Name the influential animator who had a hand in creating all of these characters: Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Screwy Squirrel, and Droopy 9. Name the Tiny Tunes character based on the Tazmanian Devil 10. In what century does Duck Dodgers take place? 11. What is Dot’s full first name? 12. What kind of contracts do the animaniacs have? 13. What company do all of the above characters come from? Requiem for the Blue Civic – Jan. 2014 Cartoons 1 Part II 14. Name one of Darkwing Duck’s Catch phrases: 15. Name the three characters in “Tailspin” that also appear in “the Jungle book” (though the universes are apparently separate and unrelated) 16. Who is this? 17. Fill in these blanks: “ Life is like a ____________here in _____________ Race cars, lasers, aeroplanes ‐ it's a _______blur You might ______ a _____ or rewrite______ ________! __‐__!” 18. What was the name of Doug Funnie’s dog? 19. Whose catchphrase is: “So what’s the sitch”? 20. What kind of an animal is Ron Stoppable’s pet, Rufus? 21. -

Muffled Voices in Animation. Gender Roles and Black Stereotypes in Warner Bros

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Bra şov • Vol. 4 (53) No.2. - 2011 • Series IV Series IV: Philology and Cultural Studies MUFFLED VOICES IN ANIMATION. GENDER ROLES AND BLACK STEREOTYPES IN WARNER BROS. CARTOONS: FROM HONEY TO BABS BUNNY Xavier FUSTER BURGUERA 1 Abstract: This essay will use a Tiny Toons episode, “Fields of Honey”, as an excuse to survey stereotypical female and racial roles depicted in the most representative cartoons of the 20 th century. It is particularly relevant to go back to a 1990s cartoon series since, in that decade, Western animation was undergoing crucial changes in its conception which would determine significantly the upcoming animated instalments of the new millennium. Moreover, contemporary cartoonists are now those grown-up children that watched the earlier American cartoons whose allegedly unconscious female discrimination and “innocent” racism might somehow have been fossilised among its audience and become thus perpetuated in the culture and imaginary of the globalised world. Finally, it is also important to be acquainted with the contents of cartoons understood as children’s products, especially in a period where television is taking over most of the parental duties and guidance in children’s development into adulthood. Key words: popular culture, media and animation studies, gender roles, black stereotypes, Warner Bros., Tiny Toons. 1. Introduction: All this and rabbit stew Animation, as well as real-image featurettes, became an extension of the Cartoons were born at the beginning of theatrical ritual. Cartoons started to be th the 20 century, thanks to the projected before a theatrical performance technological revolution that was changing or as interludial pieces as soon as 1911. -

Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Theses School of Film, Media & Theatre Summer 7-31-2018 Animating Social Pathology: Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation Wolfgang Boehm Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_theses Recommended Citation Boehm, Wolfgang, "Animating Social Pathology: Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animating Social Pathology: Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation by Wolfgang Boehm Under the Direction of Professor Greg Smith ABSTRACT This thesis grounds an unstable ontology in animation’s industrial history and its plas- matic aesthetics, in-so-doing I find animation to be a site of rendering visible a particular con- frontation with an inability to properly rationalize, ossify, or otherwise delimit traditionally held boundaries of motility. Because of this inability, animation is privileged as a form to rethink our interactions with media technology, leading to utopian thought and bizarre, pathological behav- ior. I follow the ontological trend through animation studies, using Pixar’s WALL-E as a guide. I explore animation as an afterimage of social pathology, which stands in contrast to the more lu- dic thought of a figure such as Sergei Eisenstein, using Black Mirror’s “The Waldo Moment.” I look to two Cartoon Network shows as examples of potential alternatives to both the utopian and pathological of the preceding chapters. -

1 Iconology in Animation: Figurative Icons in Tex Avery's Symphony In

Iconology in Animation: Figurative Icons in Tex Avery’s Symphony in Slang Nikos Kontos The current fascination with popular culture has generated numerous investigations focusing on a wide variety of subject matter deriving primarily from the mass media. In most cases they venture upon capturing its particular effects on the social practices of various target-audiences in our present era: effects that namely induce enjoyment and amusement within a life-world of frenetic consumerism verging upon the ‘hyper-real’. Popular culture has become a shibboleth, especially for those who are absorbed in demarcating post-modernity: its ubiquity hailed as a socially desirable manifestation of the mass-circulated ‘taste cultures’ and ‘taste publics’ – along with their ‘colonizing’ representations and stylizations – found in our post-industrial society. Hence, the large quantity of studies available tends to amplify on the pervasive theme of the postmodern condition with an emphasis on pastiche and/or parody. However, before the issue of post-modernity became an agenda-setting trend, semioticians had been in the forefront in joining the ranks of scholars who began to take seriously the mass-produced artifacts of popular culture and to offer their expertise in unraveling the immanent meanings of the sign systems ensconced within those productions. Since Roland Barthes’ and Umberto Eco’s critically acclaimed forays into the various genres of popular culture during the late 50’s and early 60’s, many semiotic scholars - following their lead - have attempted to extract from these mass art-forms meaningful insights concerning the semiotic significance portrayed in them. Many of these genres such as comics, detective/spy novels, science fiction, blockbuster films, etc., have been closely scrutinized and analyzed from an array of critical vantage points covering aspects that range, for example, from formal text-elements of the particular genre to its ideological ramifications in a socio-historical context. -

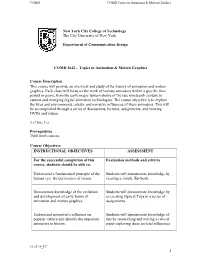

COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics

COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics New York City College of Technology The City University of New York Department of Communication Design COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics Course Description This course will provide an overview and study of the history of animation and motion graphics. Each class will focus on the work of various animators within a specific time period or genre, from the early magic lantern shows of the late nineteenth century to current and emerging digital animation technologies. The course objective is to explore the lives and environments, artistic and narrative influences of these animators. This will be accomplished through a series of discussions, lectures, assignments, and viewing DVDs and videos. 3 cl hrs, 3 cr Prerequisites 3500 level courses Course Objectives INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT For the successful completion of this Evaluation methods and criteria course, students should be able to: Understand a fundamental principle of the Students will demonstrate knowledge by human eye: the persistence of vision. creating a simple flip-book. Demonstrate knowledge of the evolution Students will demonstrate knowledge by and development of early forms of re-creating Optical Toys in a series of animation and motion graphics. assignments. Understand animation's influence on Students will demonstrate knowledge of popular culture and identify the important this by researching and writing a critical animators in history. paper exploring these societal influences. 10.25.14_LC 1 COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT Define the major innovations developed by Students will demonstrate knowledge of Disney Studios. these innovations through discussion and research. -

Blitz Wolf (Der Gross Méchant Loup), De Tex Avery

Blitz Wolf (Der gross HIDA méchant loup), de Tex Avery Présentation de l’oeuvre Fiche technique Réalisateur : Tex Avery Producteur : MGM (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer) Genre: Film d’animation Pays: Etats-Unis Date de sortie : 22 août 1942 Durée: 10 minutes Synopsis Une variante sur l'histoire bien connue des trois petits cochons, avec un loup qui a bien des points communs avec Adolf Hitler. 1ère approche de l’œuvre 1) Quelle impression cette œuvre vous fait-elle? Quels sentiments avez-vous en la visionnant ? 2) Quelles questions vous posez-vous en regardant ce dessin animé? Contexte historique 3) D’après la date de ce dessin animée, quel est le contexte historique aux Etats-Unis ? (aidez- vous de la chronologie vue en cours) Décembre 1941 : entrée en guerre des USA après l’attaque japonaise sur Pearl Harbor Août 1942 : les Américains sont en pleine guerre dans le Pacifique Contexte artistique Le premier dessin animé de l’histoire du cinéma est présenté en 1906. Il s’intitule « Humorous Phases of Funny Faces » (Phases amusantes de figures rigolotes). Il a été réalisé à partir de dessins à la craie sur un tableau noir. Les Américains vont très vite s’emparer de cette nouvelle technique d’animation et créer une véritable industrie du cinéma d’animation. Trois studios émergent dans l’entre-deux guerres: les studios Fleischer (qui ont crée les personnages de Popeye ou Betty Boop), la Walt Disney Company (et son célèbre Mickey Mouse) et les studios de Tex Avery (à qui l’on doit les personnages de Bugs Bunny ou Droopy). -

Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Bob Clampett 电影 串行 (大全) Book Revue https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/book-revue-4942952/actors Looney Tunes Golden Collection: https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-golden-collection%3A-volume-3-12125823/actors Volume 3 The Great Piggy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-great-piggy-bank-robbery-5690966/actors Bank Robbery Looney Tunes Golden Collection: https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-golden-collection%3A-volume-5-6675683/actors Volume 5 What's Cookin' https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/what%27s-cookin%27-doc%3F-7990749/actors Doc? Buckaroo Bugs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/buckaroo-bugs-2927464/actors The Big Snooze https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-big-snooze-7717795/actors Looney Tunes Super Stars' Porky https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-super-stars%27-porky-%26-friends%3A-hilarious-ham-6675713/actors & Friends: Hilarious Ham Bugs Bunny Gets https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bugs-bunny-gets-the-boid-2927739/actors the Boid Looney Tunes Super Stars' Daffy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-super-stars%27-daffy-duck%3A-frustrated-fowl-6675706/actors Duck: Frustrated Fowl Wagon Heels https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/wagon-heels-7959643/actors Looney Tunes Showcase: Volume https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looney-tunes-showcase%3A-volume-1-6675699/actors 1 Africa Squeaks https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/africa-squeaks-4689595/actors Get Rich Quick https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/get-rich-quick-porky-16250714/actors